To investors,

I hope each of you had a great holiday weekend. This week is going to be a little different than our normal schedule. I am in the middle of reading a fascinating book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth by Robert J. Gordon. Although the book is a New York Times bestseller, there are very few people I know who have read it.

Gordon published the book in 2017 and it lays out a unique argument — he “challenges the view that economic growth will continue unabated, and demonstrates that the life-altering scale of innovations between 1870 and 1970 cannot be repeated.” This is an important topic given the current macro environment, coupled with the identified need for the United States to bring manufacturing and supply chains back home, as well as the missing GDP growth that has contributed to 140% debt-to-GDP domestically.

I’ll be writing a few times this week with thoughts about the book, lessons learned, interesting data points, and any “ah-ha” moments that relate to the present day. The book is more than 700 pages, so this will be somewhat of a personal challenge to see if I can read fast enough to have something to write each day :) If you would like to read alongside me, you can purchase the book from Amazon (note: I get nothing from this and am not affiliated with the book or the author - just a fan of the book so far).

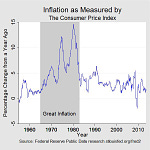

Gordon’s main premise for the book is quite simple. Economic growth in the United States exploded between 1920 and 1970. The real output per US person during the 20th century doubled approximately every 32 years. This is in stark contrast to other times in history, including “no economic growth over the eight centuries between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages” and “real output per person in Britain between 1300 and 1700 barely doubled in four centuries.”

According to Gordon:

“Scholars struggled for decades to identify the factors that caused productivity growth to decline significantly after 1970. What has been missing is a comprehensive and unified explanation of why productivity growth was so fast between 1920 and 1970 and so slow thereafter. This book contributes to resolving one of the most fundamental questions about American economic history.”

To answer the question of why productivity growth was so fast in the 50 years preceding 1970, we have to look at Gordon’s “central thesis” — some inventions are more important than others. If I was to mention that idea to a random stranger on the street, most people would likely agree. They may even look at me like I was crazy for suggesting it WAS NOT true. But the traditional economist’s view of the world does not hold this idea as an accepted idea.

Giorgos Kallis eloquently explained the widespread belief when he wrote:

“One argument of those who defend growth is that growth is the natural and inevitable course of the economy. Liberated from governmental or other restrictions, and left to their own powers, entrepreneurs will make an economy grow, as they are endlessly inventive in growing their own incomes. Growth is then seen as the natural product of a free, ‘self-regulated market’. The destiny of the economy, unless human institutions mess with it, is to grow, like the destiny of a newborn is to grow up, and of a small tree to grow taller and taller. The pursuit of growth according to this view is imprinted in our instincts, if not our genes. Humans, like other species, given the opportunity, expand their habitat and resource use as much as possible. It might have taken us centuries to find the word for it (‘growth’), but the desire and potential was always there.”

Surprisingly, both Gordon and Kallis agree that growth is not natural and inevitable.

This brings us to a key distinction in Gordon’s book. He acknowledges that growth has occurred since 1970, but highlights that it was mostly in “entertainment, communications, and the collection and processing of information.” This means, according to his analysis, that “the rest of what humans care about” has seen a slow down in growth, including “food, clothing, shelter, transportation, health, and working conditions inside and outside the home.”

The third distinction that Gordon makes is that the little growth that has occurred since 1970 has been captured unevenly by the US population as well. He states “the rise in inequality that since 1970 has steadily directed an ever larger share of the fruits of the American growth machine to the top of the income distribution.”

With all this said, Gordon understands that many people will disagree with him. They will point to standard of living improvements using real GDP per person, or a similar measurement. He claims that there are two major failures in this data point — “GDP omits many dimensions of the quality of life that matter to people” and “the growth of GDP is systemically understated” due to price indexes overstating price increases.

He suggests that a better measurement of the standard of living is to use Gary Becker’s theory of time allocation. Becker argued in his seminal paper:

“Throughout history the amount of time spent at work has never consistently been much greater than that spent at other activities. Even a work week of fourteen hours a day for six days still leaves half the total time for sleeping, eating and other activities. Economic development has led to a large secular decline in the work week, so that whatever .may have been true of the past, to-day it is below fifty hours in most countries, less than a third of the total time available. Consequently the allocation and efficiency of non-working time may now be more important to economic welfare than that of working time; yet the attention paid by economists to the latter dwarfs any paid to the former.”

This work allows for a categorization of time spent in the household and on non-work activities. The thought process is if you’re going to measure the standard of living, it may help to measure what people are doing with their time outside of working.

Made Me Think

There were a lot of arguments in the beginning of the book that made me think more critically, but Gordon used a simple example that reminded me that even the most complex topics can be boiled down to a few simple elements. He argued “just as the thousands of elevators installed in the building boom of the 1920s facilitated vertical travel and urban density, so the growing number of automobiles and trucks speeded horizontal movement on the farm and in the city.”

Moving up and down, and side-to-side, at a faster pace. Not exactly rocket science. But the elevators and cars created efficiency, innovation, and an economic boom that may be hard to recreate.

Facts About Inventors

My favorite section of the book so far was titled “Inventions and Inventors.” In it, Gordon makes two simple arguments. First, “the major inventions of the last nineteenth century were the creations of individual inventors rather than large corporations.” That seems like a significant difference from majority of the innovations that we hear about today.

The second argument was all about location and nationality.

“Although this book is about the United States, many of the inventions were made by foreigners in their own lands or by foreigners who had recently transplanted to America. Among the many foreigners who deserve credit for key elements of the Great Inventions are transplanted Scotsman Alexander Graham Bell for the telephone, Frenchmen Louis Pasteur for the germ theory of disease and Louis Lumière for the motion picture, Englishmen Joseph Lister for anti-septic surgery and David Hughes for early wireless experiments, and Germans Karl Benz for the internal combustion engine and Heinrich Hertz for key inventions that made possible the 1896 wireless patents of the recently Italian immigrant Guglielmo Marconi. The role of foreign inventors in the late nineteenth century was distinctly more important that it was one hundred years later, when the personal computer and Internet revolution was led almost uniformly by Americans, including Paul Allen, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, Larry Page, and Mark Zuckerberg. Among the pioneering giants of the Internet age, Sergei Brin is one of the few to have been born abroad.”

My Favorite Quote

“The past is a matter of record, the future a matter for speculation.” - Robert J. Gordon

Noteworthy data points

“According to the great historian of economic growth, Angus Maddison, the annual rate of growth in the Western world from AD 1 to AD 1820 was a mere 0.06% per year, or 6% per century.”

“Transportation among all the Great Inventions is noteworthy for achieving 100% of its potential increase in speed in little more than a century, from the first primitive railroads replacing the stagecoach in the 1830s to the Boeing 707 flying near the speed of sound in 1958.”

“Though not a single household was wired for electricity in 1880, nearly 100% of US urban homes were wired by 1940 … In short, the 1870 house was isolated from the rest of the world, but 1940 houses were networked, most having the five connections of electricity, gas, telephone, water, and sewer.”

“The percent of the nation classified as urban (defined as population of 2,500 or more) grew from 24.9% in 1870 to 73.7% in 1970.”

“One of the most important product introductions was the Model T Ford, which went on sale in 1908 at an initial price of $950. Over the next fifteen years, Henry Ford’s introduction of the assembly-line method of manufacturing to the production of automobiles brought an astonishing reduction in price to $269 in 1923.”

“There were only 8,000 registered motor vehicles in 1900, yet there were 26.8 million just three decades later.”

The Critics

The idea that economic growth is slower today than 1920-1970, and that it will stay that way moving forward, will obviously shake the foundational beliefs of a number of people. The largest portion of critics, which Gordon calls “techno-optimists,” allegedly “predict a future of spectacularly faster productivity growth based on an exponential increase in the capabilities of artificial intelligence.”

This explicit call out of critics is fascinating to me because I would generally put myself in the techno-optimist category, but I have found myself nodding along with Gordon’s arguments so far. I am excited to read the rest of the book to see where I fall as I learn more about his evidence and perspective.

One Surprise

The biggest surprise to me has been Gordon’s identification of lower productivity and economic growth post-1970, yet I haven’t seen a single mention of the United States monetary policy leaving the gold standard. Given how much attention economists have put on this historic decision, I would have expected to see an analysis of its impact, regardless of whether Gordon thought it was important or not.

Add in the fact that many in the bitcoin community would argue “fix the money, fix the world” and you can see where monetary policy could play an important role in future economic growth. Maybe we are just early in the book and this analysis will come later, but we’ll see.

One Ask

I would love to hear from each of you. If you have read the book, or you have thoughts about the information, data, and quotes above, please leave a comment on this post and I will do my best to respond to all of them. You can comment from the Substack app or you can click this email, view it in a browser, and scroll to the bottom of the page.

What do you agree with so far? What do you disagree with? Any surprises? Or any additional information that you think would be interesting to add?

Looking forward to everyone’s thoughts. Hope you have a great start to your day. I’ll talk to everyone tomorrow.

-Pomp

David Rubenstein is a well known entrepreneur and investor, the Co-Founder of The Carlyle Group, and hosts his own show through Bloomberg.

In this conversation, David gives a masterclass on his tips and lessons learned in the past 50 years of investing and entrepreneurship. We also discuss the current economic environment, the future of the United States, young people leading the next revolution through crypto, and how to become a better thinker and decision maker.

Listen on iTunes: Click here

Listen on Spotify: Click here

Is India The Next Silicon Valley?

Podcast Sponsors

These companies make the podcast possible, so go check them out and thank them for their support!

Alto IRA can help you invest in crypto in tax-advantaged ways to help preserve your hard earned money. There are no setup or account fees, and it’s all you need to do to invest in crypto tax free. Open an Alto CryptoIRA to invest in crypto tax-free by clicking here.

Eight Sleep is the most advanced solution on the market for thermoregulation by pairing dynamic cooling and heating with biometric tracking. Click here to check out the Pod Pro Cover and save $150 at checkout.

FTX US is the safe, regulated way to buy digital assets. Trade crypto with up to 85% lower fees than top competitors by signing up at FTX.US today.

Amberdata provides the critical data infrastructure enabling financial institutions to participate in the digital asset class. We deliver comprehensive data and insights into blockchain networks, crypto markets, and decentralized finance. Download our Digital Asset Data Guide here today.

SiGMA is the bridge between iGaming, online sports betting, and emerging technology, such as Blockchain, NFTs, fintech, GameFi, metaverse, and AI, is loud and clear. The largest global summit of this kind is heading to Malta from November 15 to 17. Log on to AIBC.WORLD or SiGMA.WORLD to see all our upcoming global summits!

Bullish is a powerful exchange for digital assets that offers deep liquidity, automated market making, and industry-leading security. Click here to learn more.

Valour represents what’s next in the digital economy -- providing simplified, trusted access to crypto, decentralized finance and Web 3.0 investment opportunities. For more information visit valour.com

Unstoppable Domains’ 10 NFT domain endings are now fully integrated with Trust Wallet. Claim your Unstoppable Domain here today.

Compass Mining is the world's first online marketplace for bitcoin mining hardware and hosting. Visit compassmining.io to start mining bitcoin today!

LMAX Digital is the market-leading solution for institutional crypto trading & custodial services. Learn more at LMAXdigital.com/pomp

Exodus is the world’s leading desktop, mobile, and hardware crypto wallets, with over 150 assets. Founded in 2015 to empower people to control their wealth. Visithttp://exodus.com/pomp today.

You are receiving The Pomp Letter because you either signed up or you attended one of the events that I spoke at. Feel free to unsubscribe if you aren’t finding this valuable. Nothing in this email is intended to serve as financial advice. Do your own research.

The Rise and Fall of American Growth