Lawmakers in Papua New Guinea have voted in favor of a constitutional amendment affirming that the Pacific island nation is a Christian country.

You might expect local Catholic representatives to be delighted. But you’d be wrong.

How Christian is PNG, statistically speaking? What does the amendment say? And why are Catholic leaders critical of the change?

The Pillar takes a look.

How Christian is PNG?

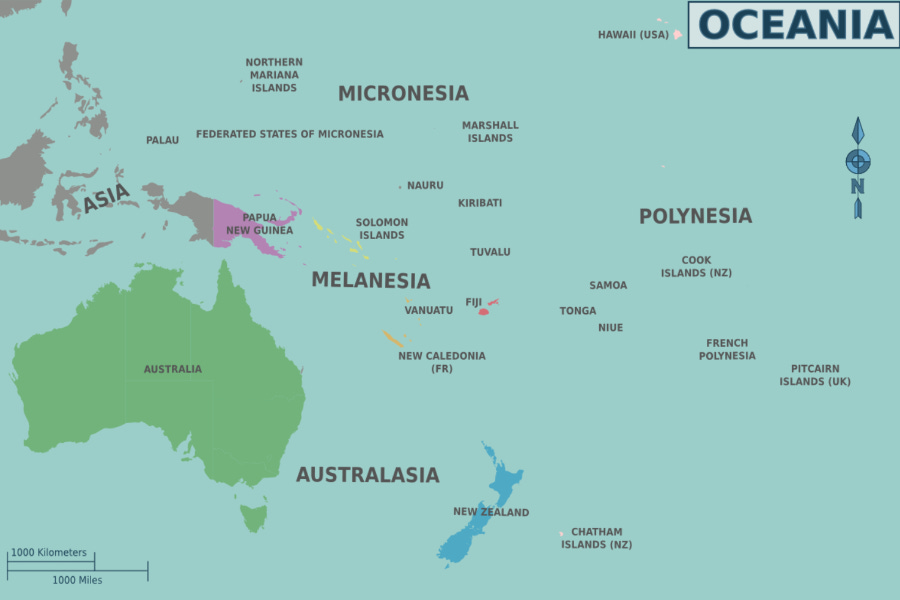

With around 11.8 million people, PNG has the second-largest population in Oceania, after Australia. The country, which gained independence from Australia in 1975, occupies the eastern half of New Guinea, the world’s second-largest island after Greenland. (The western half belongs to Indonesia).

Around 40% of the population lives below the extreme poverty line, although the country is rich in natural resources including oil and gas, and PNG has one of the world’s highest crime rates.

PNG’s first recorded Christian missionaries were French Marist Fathers, who arrived in the region in the 1840s, though the faith was not firmly embedded until around the 1870s.

According to a 2011 census, 95.6% of Papua New Guineans identify as Christian. Catholics form the largest Christian grouping, accounting for 27% of the population, followed by Lutherans at 19.5%.

When Pope Francis visited the country in September 2024, the Vatican estimated that the country had 2.5 million Catholics, including 1 cardinal, 27 bishops, and 600 priests.

According to the U.S. Institute of Peace, Christian communities in PNG “have a broader reach than institutions of the state.”

“The government is absent in many remote communities, meaning that churches often play a significant role in providing public services,” it said. “During times of conflict, when police or other state agencies are absent, religious leaders resolve disputes, and rebuild peace.”

What does the amendment say?

Members of the National Parliament of Papua New Guinea voted March 12, with an 80 to 4 split, in favor of amending the preamble to the country’s constitution.

Following the vote, the preamble will now say: “[We, the people of Papua New Guinea] acknowledge and declare God, the Father; Jesus Christ, the Son; and Holy Spirit, as our Creator and Sustainer of the entire universe and the source of our powers and authorities, delegated to the people and all persons within the geographical jurisdiction of Papua New Guinea.”

This considerably strengthens the previous reference to Christianity in the preamble, which said “[we] pledge ourselves to guard and pass on to those who come after us our noble traditions and the Christian principles that are ours now.”

Other changes passed by parliamentarians included the recognition of the Bible as an official national symbol.

But the changes fall short of turning PNG into a Christian state. As a 2020 paper published by the country’s National Research Institute noted, Christian states not only declare Christianity to be the nation’s religion in their constitution but also have a state church.

PNG certainly doesn’t meet the second requirement and would have difficulty doing so. As the paper said, “the conversion or recognition of one of the existing Christian denominations in PNG to a state church might generate tension and animosity among the Christian denominations in the country.”

Following last week’s amendment, section 45 of PNG’s constitution continues to guarantee freedom of conscience, thought, and religion.

Why don’t Catholic leaders approve?

The Catholic case against the constitutional amendment was set out at length in a March 18 essay by Fr. Giorgio Licini, a former secretary general of PNG’s bishops’ conference who now works for Caritas Papua New Guinea.

Licini argued that the amendment sought to address a national identity crisis created by three contending forces shaping PNG: a deep ancestral heritage, Western colonial rule, and 21st-century technology.

It was also an attempt to differentiate PNG from its Muslim neighbor Indonesia, and the secular liberal Australia and New Zealand, the priest said.

“Protestant, Evangelical, and Pentecostal pastors from both mainline Churches and new groups believe that national harmony and progress will materialize when Christianity is formally and emphatically recognized by the national constitution,” Licini wrote.

“At that point, everybody will rally in unity around the new national identity pillar to defeat violence, corruption, ignorance, and personal interest.”

The amendment is particularly cherished by PNG’s Prime Minister James Marape, a member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, who believes it will help to realize his dream of turning PNG into the “richest black Christian nation on planet earth” within 10 years of his election in 2019.

But Licini suggested that disillusion would set in after the amendment failed to produce the social transformation its Christian advocates hoped for. PNG, he said, could easily end up poorer rather than richer in 2029 than a decade earlier.

Licini was not the only Catholic expressing skepticism. Fr. Miguel de La Kale, who helped to show Pope Francis around the remote city of Vanimo last September, said the amendment was superfluous.

“Michael Somare, the founder of the country, was a Catholic, meaning we are a Christian country already ... but for us Catholics, we are also Christian in our mentality, we don't need to declare a country to be Christian,” he said.

“For us, it’s not necessary, we know the Christian principles are there from the very beginning; they are in the constitution already.”

The priests’ views are shared by the country’s bishops. Last year, the bishops’ conference expressed strong opposition to the change in a letter to the country’s constitutional and law reform commission.

Referring to the setting of a King James Bible in a place of honor in parliament in 2015, the letter said: “While PNG already has the KJV Bible in the House since 2015 and boasts about being over 90% Christian, we see no reduction in corruption, violence, lawlessness, and offensive conduct of parliamentary debate.”

The bishops’ conference complained that the amendment had “been pushed by a group of unrepresentative pastors and professionals without wider consultation and transparency among Churches.”

The solution to PNG’s problems, it said, “does not lie in the rejection of our traditions, the transformation into a confessional state, the promotion of religious fundamentalism, Christian nationalism, or an ideology of that sort.”

The Catholic Church in PNG, in other words, doesn’t buy into the worldview of the amendment’s proponents and believes its failure to improve the country’s situation will soon be apparent.