As the new year begins, and as fallen cryptocurrency mogul Sam Bankman-Fried prepares for the legal battle of his life, the industry he helped drag low continues to struggle—with revenue, with investor confidence, with yet more crime. If you went in on BTC or ETH or DAOs or NFTs, it’s been bad news all around.

But for the people reporting that news, it’s been a golden age.

Recall that the disgrace of Sam Bankman-Fried and his crypto exchange FTX began with a report from a crypto-centric news website: On Nov. 2, CoinDesk published a leaked balance sheet from the SBF-founded hedge fund Alameda Research that made the business look not just iffy, but worryingly intertwined with FTX. Around the same time, the independent newsletter Dirty Bubble Media performed its own financial analysis of Alameda, asking whether the company was actually insolvent. Then, following FTX’s collapse in early November, many of the juiciest and weirdest revelations about the company came from outsider sources. CoinDesk was first to the Bahamian orgy mansion allegations, for better or for worse. SBF copped to making GOP dark-money donations in a phone call with a Bitcoin enthusiast named Tiffany Fong, the audio of which she later posted on YouTube to great aplomb. (Its fans might have included federal prosecutors from the Southern District of New York, who accused SBF of campaign finance violations, among many other charges.) Who is Tiffany Fong? “I’m not an actual journalist employed by anybody,” she told me.

As this crypto implosion has gone on, “traditional” media ventures—including the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, and New York magazine—have more than carried their weight, as have digital outlets like Vox, Bloomberg, and Puck. Andrew Ross Sorkin’s grilling of SBF at the New York Times DealBook Summit was harsher than many expected, following an earlier Times interview with the founder that many criticized as a “softball.” But the outraged crypto communities paying attention to this news saga have preferred to cheer for more homegrown sources. After Fong released the explosive audio of her call, members of Crypto Twitter praised her for exposing what the mainstream media couldn’t.

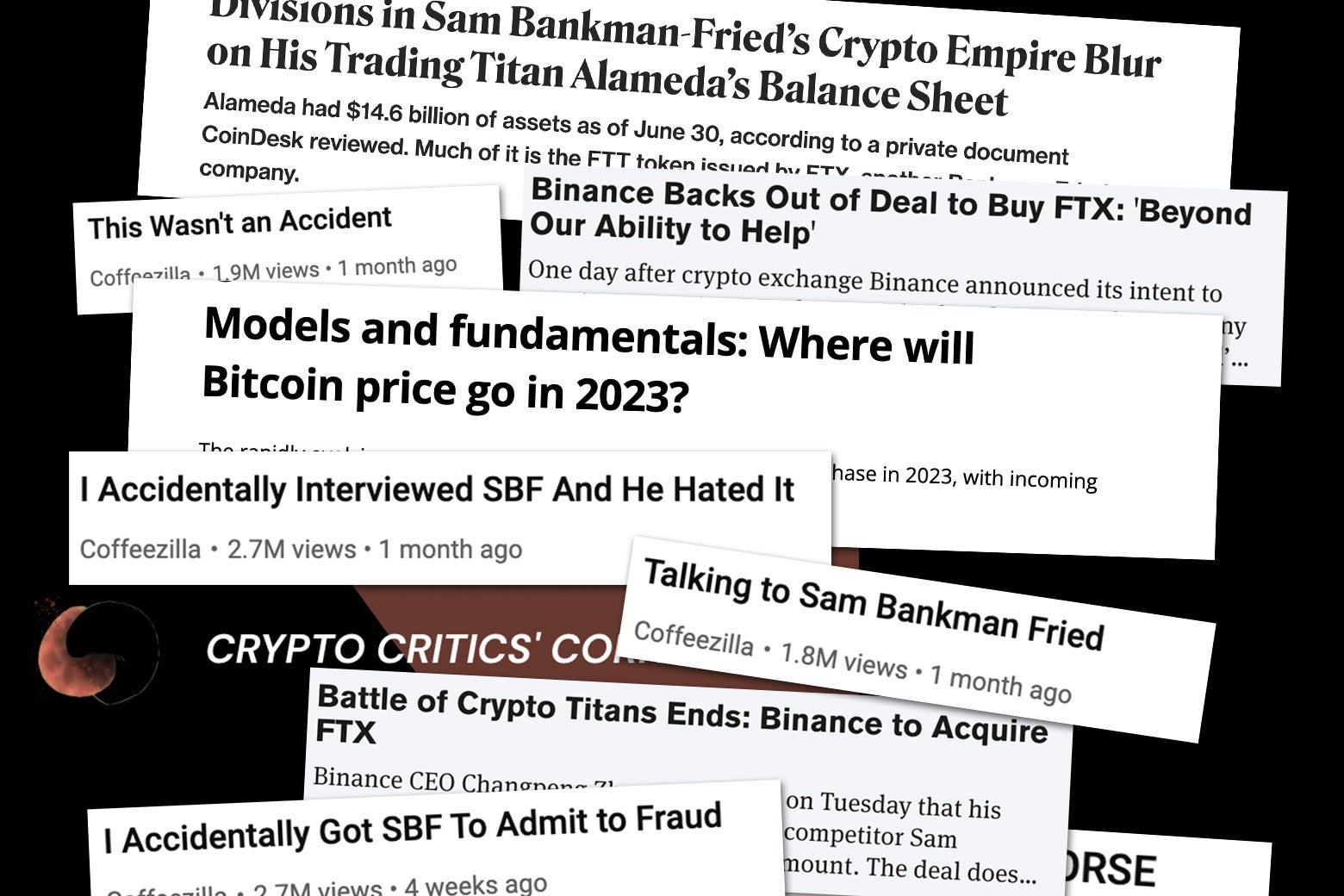

It’s hardly surprising that the cryptocurrency industry—which arose, with Bitcoin, from the wreckage of the financial crisis as an alternative to fiat economics—widely distrusts traditional media sources. But in FTX’s case especially, enthusiasts have been able to turn to “citizen journalism,” whether Fong or Dirty Bubble or the popular YouTuber Coffeezilla, for legitimate news scoops and blunt confrontations with SBF, in contrast with a financial press that was far too deferential to the crypto titan in the past and even up through now.

It’s not unfair to “traditional” media (of which I am obviously a participant!) to question how it got SBF so wrong for so long. It’s also important not to exaggerate how much “better” amateur coverage of FTX has been compared with traditional media; several overhyped Twitter Spaces hosted by crypto bros attempting to catch SBF in the lie turned out to be rather sloppy. And the crypto press did its share of SBF boosting over the years. As a CoinDesk op-ed noted, “The media, perhaps especially crypto-native publications, is complicit in the rise of Bankman-Fried.”

Still, it is remarkable to consider how unconventional the exposure of Sam Bankman-Fried really was. Especially given that CoinDesk, which earned a new level of prominence after its Alameda scoop, also itself got caught up in the crypto-industry contagion its reporting kicked off. The site is owned by the company Digital Currency Group, whose holdings include several crypto businesses. So when the scandal walloped the cryptocurrency markets, DCG took a financial hit, as Semafor reported, and is apparently looking to sell off the website. (The company is also facing various other issues, including a public beef with the Winklevoss twins. Crypto, man.)

That a publication would report something that blows back on its parent company is not unusual; the Jeff Bezos–owned Washington Post still reports on Amazon’s ugly ground-level working conditions. But it may seem strange to a lay observer that crypto-centric publications, which are invested in how the market fares—thanks to crypto advertising and traffic fueled by general interest—wouldn’t just take that money and run with it. As Crypto Critics’ Corner co-host Cas Piancey put it to me: “When your business model relies on cryptocurrency company advertisers, how critical can you possibly be of them if you don’t want to lose them as clients?”

This is a conundrum further compounded by the way crypto-market troubles can then hit these publications’ bottom lines—not just in the example of DCG and CoinDesk, but also in the way crypto companies slow down ad buys or general investments in leaner times. Just look at how industry ad spending declined last year alone. Or at how the CEO of the news site the Block stepped down after confessing to taking undisclosed funds from SBF.

There are, indeed, publications that seem to mainly serve as pro-crypto or -Bitcoin propaganda. There are also those that also sternly follow old-school reporting guidelines and employ veterans of institutions like the Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg. And then there are the independent vigilantes. I decided to talk to some key people in the crypto-media space to see whether they think their future looks bright, or whether they too will be holding on for dear life.

To hear from the editors in chief of various crypto publications, there is a strong need for journalistic principles in their sector. “I think there is too much rah-rah cheerleading in the industry,” said Daniel Roberts, who runs the news site Decrypt. “We try to cover things with integrity.”

Roberts has a background in the mainstream media, as a former Yahoo Finance reporter who was writing about Bitcoin going back to 2011. He only joined Decrypt in 2021, when it appeared that cryptocurrency “no longer felt niche” as a coverage topic, and after he noticed flaws in media approaches to digital economics. “The big publications used to only cover crypto in a sensationalistic way, when it was booming or crashing, and now they’re finally building out crypto coverage arms,” he mentioned. “I think people separate crypto media over here, and then the big outlets like the Times, FT, Bloomberg—which are considered the ‘real’ journalistic outlets, but they often get stuff wrong.”

The balance appears to be how to be properly excited about the industry—and gain the attention of experts, and everyday readers, and crypto advertisers—while not coming off as something like a “trade pub,” a term Roberts said he resents. When it comes to Decrypt’s scrappy staff (only about 15 full-time journalists, Roberts counted), there are standards. For one, “everyone discloses whether they own crypto and how much, and no one owns more than a fractional amount,” he said. “And you should have a little so you can test it for yourself and play around with it.” Plus, “we have a couple core contributors who are extreme skeptics, which is a good thing.” But overall, Decrypt’s ethos is that “we think crypto is a fascinating phenomenon that will be around for a while.”

Kristina Lucrezia Cornèr, who heads the website Cointelegraph, expressed similar sentiments to me. “I considered my mission, when I started here in 2017, to bring quality journalism into this space, because I saw that it was a bunch of passionate crypto nerds,” she said in a video call from her native Italy. “We brought the journalism vibe to the community instead of bringing blockchain enthusiasm to the journalism space.”

Cornèr’s pre-Cointelegraph career included jobs in public relations, communications, and political research. Perhaps because of that, she says she thinks of Cointelegraph as being informational, relatable, and innovative. Cornèr pointed to stories that feature on-the-ground reporting from countries like Senegal and El Salvador as one example of what she’d like her publication to do: highlight the “human interest element” and “emotions” of crypto. “If we can’t make crypto seem like something that is part of our daily lives, then it will never go mainstream,” she told me. Another mission of Cornèr’s is to “educate not just readers but regulators,” who often “lack education”: “It’s not a critique, but an objective truth.” (Cornèr did also say some regulation “needs to happen to get rid of the bad actors.”)

Both Decrypt and Cointelegraph are independent websites with tiny staffs that very much dabble in the technology they cover. At Cointelegraph, you can purchase NFTs of custom illustrations that accompany stories, and at Decrypt, all published stories are cross-posted to the IPFS blockchain, ensuring a separate, permanent archive on the ledger. They also both have investors from the space, some of whom they’ve occasionally clashed with after certain bits of coverage. Roberts mentioned controversies over Decrypt’s more skeptical coverage of big names like the MetaMask wallet and Bored Ape Yacht Club, while Cornèr talked about a negative listicle on altcoins that got the site in trouble with an investor who was involved with one of those coins. (Cointelegraph has also garnered other critiques from crypto observers who’ve accused the site, over the years, of “posting fake news” and purposefully rushing news posts or using “biased headlines.”)

Both editors in chief noted their frustration with crypto YouTubers who moonlight as analysts, since so many of them propagate scams. They also dismissed independent bloggers and critics whom they perceive as having come to prominence simply by villainizing the entire space. “Citizen journalists replacing real, trained outlets is very silly,” said Roberts. “People should trust established outlets,” by which he means sites like Decrypt.

Still, there are perhaps some advantages to careful forms of citizen crypto journalism.

Tiffany Fong told me that the loss of her holdings in the implosion of the Celsius exchange last summer started her journey as an online voice. “Crypto was not a big part of my life prior to Celsius going down,” she said. “I only started posting [on Twitter and YouTube] when it went down because I don’t have a lot of friends in crypto in real life, so I wanted to complain about my losses.”

Those complaints, plus Fong’s persistent following of the Celsius bankruptcy proceedings, soon attracted unexpected attention. “Some Celsius employees started sending me information without prompting,” she said, even though “I’d never posted asking people for info or to send me anything.” Fong then figured that the way to utilize these secretive communications was to share it with big publications. She was mentioned in a Sept. 13 New York Times report, in which the paper reported on audio of a Celsius meeting she’d gotten hold of and credited her as the source. Incidentally, “that’s the day that Sam Bankman-Fried started following me on Twitter,” Fong told me. The two chatted “briefly” and he continued to comment on her posts, though “that was pretty much the extent of our relationship.”

When FTX filed for Chapter 11, Fong figured she’d try to personally talk to SBF—why not? “I messaged him on Nov. 11, and he responded on Nov. 16. So it really caught me off guard, because it was at almost 1 a.m. when he responded to me, and it was several days later.” It was hectic all around. “He responded to me saying that he was free for the next hour or so,” she told me. “I was, to be honest, coming home from drinks, so I really, truly was not prepared at all.”

After the conversation, Fong had no idea what to do. “I initially was not planning on posting the audio, but I was trying to figure out the best way to summarize the information with credibility, since I don’t work for a reputable outlet that people trust blindly,” she said. And the experience with the New York Times had left her somewhat jaded. “That was my first taste of working with traditional media, and it didn’t feel as critical as I would have liked,” Fong told me. “I understand they probably wanted to be neutral and unbiased on it. But it wasn’t the way that I would’ve personally interpreted the audio.”

Fong’s previous YouTube videos about Celsius had gotten some attention from other crypto pundits, like Coffeezilla, and Fong decided to use that to her advantage: “I think Coffeezilla has done some good work, so I respected that. And I thought it was kind of cool to not use traditional outlets this time.” But even though she wasn’t going back to the Times, she wasn’t giving up on basic standards. “I did want to take out the parts that he explicitly said not to repeat or were off the record, just because I think I need to abide by some sort of ethical framework,” she told me. So she worked with Coffeezilla to upload the audio and break down its most newsworthy portions, and he used his platform to boost the interview—and Fong’s own channel—as well. (Contra SBF’s claim to New York magazine that “he never gave her permission” to use the call, Fong told me, “He was aware that I would post in some format. I didn’t warn him that the actual audio would be posted, but I felt that it was the best and only way to convey all the nuances.”)

A painstaking, thought-through process for giving out such a huge piece of news is certainly preferable to the rantings of microcelebrities like BitBoy Crypto, a much-watched YouTuber who’s been accused of undisclosed crypto shilling and recently found himself back in the news after a botched attempt to infiltrate SBF’s Bahamian property. And it’s clear even to Fong that not all nonjournalist analysts are as diligent as she was: During a Twitter Space where SBF appeared and was asked about an allegation inaccurately attributed to Fong’s call, she had to speak up to fix the error herself. What Fong’s done with her reporting and analysis is one thing, but other citizen crypto journalists aren’t necessarily as rigorous; that’s perhaps why she was also able to secure another interview with SBF from his parents’ house. It helps in Fong’s case, too, that she had at least some experience in crypto going back.

Still, even though Fong has become quite prominent, it hasn’t all been fun. There were plenty of people who doubted her after the first SBF audio drop, she said, simply because they didn’t know who she was. And as bigger outlets have picked up on her reporting, she’s also faced the kinds of sexist coverage that affect so many women journalists, especially those in the tech space.

The great crypto pantsing of 2022 may have made skeptics out of just about everyone who reports on the industry, but another cadre of renegade journalists got there well before FTX became synonymous with “massive fraud.” Often, they’re not even full-time writers, or even part of the media scene; Dirty Bubble is helmed by a Michigan-based physician, and the popular Web3 Is Going Just Great blog is run by software engineer and longtime Wikipedia editor Molly White. Heck, one of the most prominent anti-crypto voices in the space right now is a former teen-soap star (and Slate contributor!).

There are others who’ve made whole careers out of crypto skepticism, like the hosts of the podcast Crypto Critics’ Corner, who don’t think much of some of their less-skeptical peers. “Cryptocurrency news desks run on a bit of access journalism,” said co-host Cas Piancey, whose podcast partner, Bennett Tomlin, also works with him at the crypto news site Protos.

Both Piancey and Tomlin have ample experience questioning the biggest names in crypto—like Binfinex and Tether and Alameda—and receiving subsequent backlash. Piancey does think, however, that he’s seeing more incredulity across the space, which, if anything, should be helpful for crypto fans. “I think crypto criticism and skepticism are good, beneficial philosophies in general, so they benefit the industry ultimately,” he said.

After all, someone’s gotta clear out the riffraff and the scammers, right? And someone has to take an even sterner approach toward the systems that underlie the mass devotion to Bitcoin and crypto, but are not exclusive to them. “It’s the way that the American economy glorifies billionaires now and glorifies amassing paper wealth and power. We cover these VCs and these glorified greed machines as though that is what winning in society looks like. And it’s really unfortunate. The media should be asking itself questions about that,” Piancey concluded. “It’s not a crypto thing—it’s like an American dream thing.” It’s perhaps for that very reason that “mainstream” outlets, from Bloomberg to Forbes, are explicitly staffing up their crypto desks, and making the industry a core part of their business and financial coverage, with more specific resources dedicated to this journalism.

And Piancey, overall, remains bullish on the prospects of crypto media even during this winter, as he declared in a Protos op-ed last month, precisely because the commentary and journalism in this space are probing further and asking deeper questions. “What is clear to me is that every cryptocurrency media outlet, whether doing fine or struggling to make ends meet, has talented and brilliant journalists, willing to sacrifice anything—seemingly their jobs!—to report the truth,” he wrote. It can’t hurt their prospects that certain CEOs keep talking.