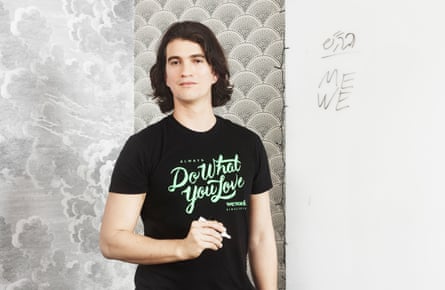

I meet Miguel McKelvey by the juice stall on the seventh floor of a glass-and-steel office building in Moorgate, central London. It’s in a large common area with a polished floor, oversized light fittings and views of the Gherkin. All around us young people are lounging on sofas, MacBooks open on their laps.

“Is that pumpkin juice?” says McKelvey, a 6ft-something 41-year-old who’s originally from Oregon, peering into the chiller cabinet.

This is WeWork, a co-working space where freelancers and start-ups come to roost, one of seven WeWorks in London and 63 across the globe that McKelvey and his partner Adam Neumann have built in under five years. From New York to San Francisco to London to Amsterdam to Tel Aviv, the model is the same: groovy furnishings, free (hand-roasted, small batch) coffee, free (craft) beer, a mixture of communal and glassed-in office spaces and a young, hard-working clientele who are building apps or offering services or trying to build the new economy, all drawn by the convenience of a monthly lease and the company of like-minded people.

It’s like a hip Silicon Valley startup, basically. It’s just that instead of being paid to work there, you have to pay them. A cool £725 a month per desk if you want a private space.

The company is not unique. In fact WeWork is one of any number of co-working spaces in London these days. There are dozens of them, but Adam Neumann, a shaggy-haired Israeli and something of a motormouth who’s 36 but looks about 22, shrugs this off. “They all came after us,” he says. “They copied us.” Well, not all of them, I say. The Hub – another co-working space – has been around for at least a decade.

“We are very different,” he says. And then: “I’m not interested in local competitors.”

But then why would he be? WeWork is a shark to other offices’ minnows. Last August it was valued at $10bn. That’s up from $5bn a few months previously, up from $1.5bn a few months before that.

It’s a staggering sum, particularly for a company few have heard of. Unlike other Silicon Valley billion-dollar valuations it hasn’t built a new search engine or claimed to have reinvented the wheel. It deals in that most old-fashioned of businesses: real estate.

Neumann doesn’t see it like that, however. He tells me how he’s just come from an event organised by JP Morgan, the bankers who are one of WeWork’s backers, where someone spoke at length about his marketing plan. “Our business is the exact opposite! We don’t need to spend money on marketing. Because we’re part of a mission and a movement. And if you’re part of a mission and a movement, your members will sell you. If they’re doing something great that makes them feel good and they’re excited about it, they’ll post it. Everyone wants to be part of something.”

This sort of talk has led WeWork to skyrocket into the same league as Airbnb and Pinterest. It is now the eighth most valuable venture-backed private company in the world. It’s not just a unicorn – a company that has achieved a $1bn valuation – it’s a “decacorn”, a company in the truly exceptional $10bn league.

In the lift on the way to our interview, I stand next to a man who’s trying to explain WeWork to a couple of his guests. “Their genius,” he says, “is that they’ve been valued not as a real estate company but as a technology company.” This is more or less it. “We happen to need buildings like Uber happens to need cars, like Airbnb happens to need apartments,” says Neumann. WeWork isn’t shared office space at all. It’s a “platform for creators”.

There’s no doubt that Neumann and McKelvey have pulled off a remarkable trick. There’s a rumour that they may shortly close another round of investment that would value the company even higher. They have investors throwing money at them, and the scale of growth is dizzying. In New York it’s already the biggest lessee of office space in the city, with 20 locations and another 50 in the pipeline for the end of 2016. The first London office only opened in 2014. By the end of this, they’ll have more than 20.

But then, Neumann says, WeWork isn’t an office, it’s a community, it’s a network. “Have you seen the app?” he asks and pulls his phone out of his pocket. “It connects everyone at WeWork all over the world.”

Neumann is the talkative one, the overexcitable one. But he and McKelvey are more similar than they are different. They were brought up thousands of miles apart but both raised by single mothers in communal environments. Neumann’s mother was a doctor in Israel and part of his childhood was spent in a kibbutz. McKelvey’s mother formed her own commune in Oregon. “She banded together with her best friends, a group of seven or eight women who all had kids. And they created a really cool kind of collective environment where we had really strong, awesome moms taking care of us kids, kind of collectively. They were super-proactive women who were interested in engaging in political and social dialogue, and set up an alternative newspaper.”

He has three sisters and a brother, two of whom work for WeWork. “And my mom is getting older and keeps asking when we’re going to do the equivalent of WeWork for older people. You know, she thinks this environment is so cool. She can’t imagine going into some assisted-living facility.”

But then WeAge could perhaps be the next logical step. WeLive – that aims to do the same for co-living that WeWork did for co-working – is their next big launch. A prototype is currently being built in Chicago, with one shortly to follow in New York, though Neumann is evasive about exactly what the model will be. Are they going to be apartments or hotels or both?

“It’s going to be a new way of living, day to day, week to week, month to month, year to year,” he says. “You will be a global citizen of the world. If you’re a member of one, you’re a member of all of them.”

Like Soho House? “No, because there you have to be voted in by a committee. And they care about how you dress and where you work. This is more like a private club that anyone can join.”

There’s no doubt it’s going to be ambitious, because everything WeWork does is ambitious. An investor’s presentation was leaked online claiming that by 2018 WeLive will be pulling in $636m. Which is quite a big figure given that it hasn’t actually launched, and no one is clear, as yet, whether anyone will want to live in what BuzzFeed described as “like living in the Disneyland version of startup life”.

The Washington prototype will have “neighbourhoods” with expansive common areas, commercial-grade kitchens and dining areas. Think a hipster commune, or college life for grown-ups. I look at my notepad and try to make sense of the figures. “According to your internal projections you expect to have 260,000 WeWork members in 376 locations and 34,000 WeLive members in 69 locations. Is that right?”

“The number of members is right,” Neumann says. “Locations will vary. If you have larger buildings, you need fewer locations.”

Really? “Those are low numbers,” he adds.

The two met in New York when Neumann was a serial entrepreneur trying and failing in the babywear business and McKelvey was an architect designing retail spaces. They became friends and discovered they shared certain bonds. “It was even the same movie that made us both initially want to move to New York,” says McKelvey. “Wall Street.”

Gordon Gekko isn’t very Oregon commune, I say. “Yeah, but that’s the point. The endeavour can be many different things. But you still have to be pushing to the extreme to achieve it.”

In fairness, they probably are. They have six children between them, and the life of decacorn founder doesn’t involve much sleep. And while they talk the talk and then some, there’s a certain guileless quality to them. They were involved in a high-profile labour dispute in US cities that saw their cleaners, who worked for a contractor, picket their offices demanding better wages and conditions. They responded – eventually – by taking the jobs in-house and providing proper employment benefits. Have you learned from that? Are your cleaners in London staff?

“I’ll find out,” says Neumann. And he issues Siri with a command. “I’m dyslexic,” he explains. A minion appears. “They’re agency,” he says.

“We’re scaling the company,” says Neumann without a beat. “We can’t do everything in a day.”

The disjunction between the $10bn valuation and the minimum wage most agency cleaners are paid is pretty stark, but also standard in the new tech economy. It’s the price of “disruption”, the semi-mythical quality that all technology firms claim to have. Uber has disrupted taxis, Airbnb hotels. What exactly are you disrupting?

“Just look out of this window and you’ll see it,” says Neumann. We’re in a glass-walled conference room overlooking the atrium of the WeWork building. We can see seven floors of eager young things arrayed over designer chairs, tapping into laptops.

“Driving here, I looked into the windows of office buildings in London. People look miserable. See here? They’re working but they’re smiling. What we’re disrupting is work, because it used to be: ‘I need to work because that’s my job, then I use that money to live.’ I don’t believe that’s true. I believe that your life should be about creating your life’s work. I believe that when you do what you love you find higher levels of satisfaction that can compensate for lower income. I actually think most people do what they love because it’s really important to them.”

Neumann’s own lightbulb moment, he says, came when he was 28. He’d been running a baby clothes company and “my wife, then-girlfriend, said: ‘Look, you’re all confused. You’re trying to make money – that’s not how you build a great business. What’s your intention? What’s your meaning behind what you do? How is it going to be meaningful to other people?’”

If this sounds like something you might read on Gwyneth Paltrow’s website, Goop, it may be because his wife, Rebekah Paltrow Neumann, is her cousin. But it’s all very well talking about communities and meaning, but actually WeWork is, first and foremost, a commercial enterprise with a $10bn valuation and not some hippy lovefest. It reminds me of the last episode of Mad Men, I say. Don Draper has a nervous breakdown and ends up in a hippy retreat. The last scene sees him chanting on the grass and then the legendary Coca-Cola ad, “I’d like to teach the world to sing!”, strikes up, the inference being that Don has repackaged the counterculture to do capitalism’s work. Haven’t Neumann and McKelvey just channelled the ideals of their youth into a $10bn business of the type that truly does belong in Gordon Gekko’s old office? Albeit with a feelgood twist?

“There are two parts to that story that I think are interesting,” says McKelvey. “The first is that while I did grow up, as Adam did, in some idealistic formulation that was purposeful, at the same time I grew up in the town where Nike was founded. Where it grew from being something being run out of the back of a car trunk to one of the biggest companies in the world. That was really one of the only bright spots in the town . I’ve seen how business can transform communities. Commerce is a core component of pretty much any successful society. We’re realistic about that.”

A friend of mine, I tell him, who had been working for a start-up in another of WeWork’s London offices, had told me that it was the buzziest place she’d ever worked. Though she’d worried that the £700-plus-desk fee was one reason the startup was running out of cash. Two days later they’d let her go because they needed to cut their costs.

Is there a moral there, I ask. Is that the price of being cool? Working in a place with funky wallpaper probably does affect the fabric of your life, but at the same time it’s pretty shallow, isn’t it? Not to mention expensive. “I don’t think coolness has anything to do with it,” says McKelvey. “It’s being surrounded by people who are on that journey to try and find however they define success.”

And the Guardian, Neumann points out, “is our biggest member in the world”. When Guardian US needed larger offices last June, instead of taking a lease on a conventional office building, it entered into a long term agreement for two floors of self-contained office space in a WeWork building in Manhattan.

WeWork has made a profit from day one, Neumann says. By carving up conventional office space, and throwing in free coffee and designer chairs, they’ve been able to charge 10 times per square foot more than you can for conventional office space. “We have 41,000 members as of today,” says Neumann. “And I make $10,000 per person per year on a 40% margin. I’ve been profitable since the second month of the creation of this business.”

Critics argue that the economics are based on WeWork taking on long leases which are discounted in the first years, meaning overheads will rise in future years. Come a recession, it will have large fixed expenses. But recessions are exactly when small businesses will want to cut overheads and move into shared space, argues Neumann.

“Do you want some wine?” he asks. “C’mon! Let’s have a glass of wine.” And he holds up his phone. “Siri, a bottle of red and three glasses to the conference room.” He struggled at school and went straight into the Israeli navy, missing out on college. It’s what inspired some of WeWork’s more fun innovations: an annual summer camp and the free bar. “We ran the numbers on it and it wasn’t that expensive. I felt that, as a business, having a beer together at six o’clock really brings people together.”

The wine arrives and down below a music system is cranking up. They’re throwing a party for 700 people that night, he says. Mark Ronson is DJ-ing. It’s office space, but not as we know it.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion