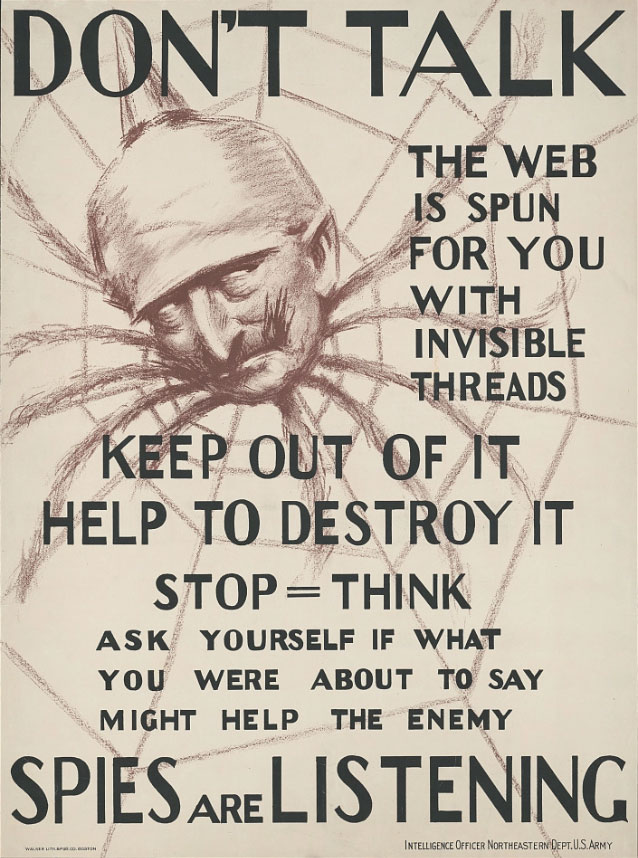

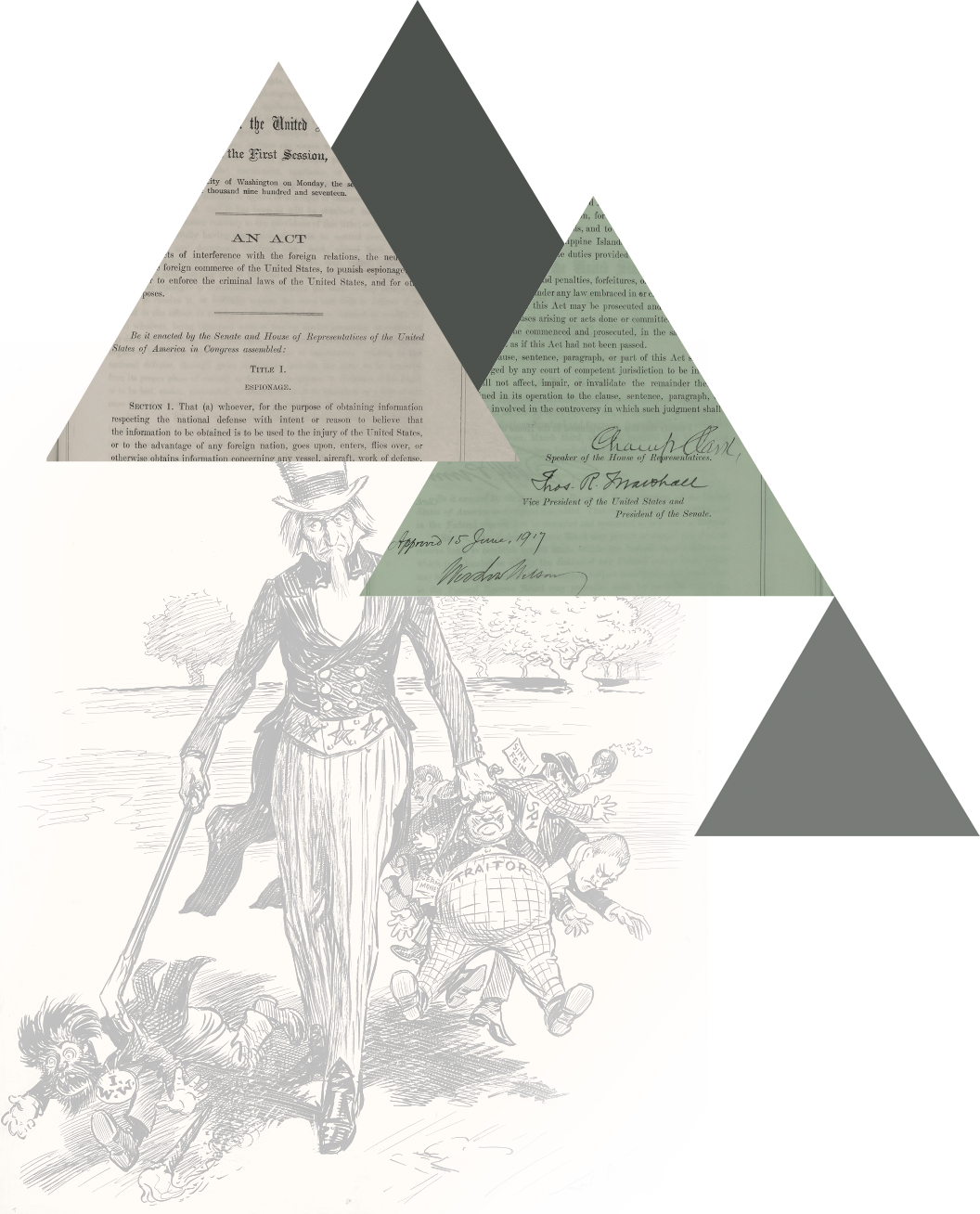

first German operatives set to work on American soil, President William Howard Taft signed into law the Defense Secrets Act of 1911, criminalizing both the collection of information from military installations and facilities, and the sharing of sensitive information with those who lacked appropriate clearances. After the United States entered the war, in June 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act, building on the 1911 law, with important new elements added in.

The Espionage Act broadly sought to crack down on wartime activities considered dangerous or disloyal, including attempts to acquire defense-related information with the intent to harm the United States, or acquire code and signal books, photographs, blueprints, and other such documents with the intention of passing them to America’s enemies. The Act also outlawed false statements intended to interfere with military operations; attempts to incite insubordination or obstruct the recruitment of troops; and false statements promoting the success of America’s enemies. Those charged with violations were subject to a $10,000 fine and twenty years imprisonment. If the crimes were committed during wartime, the punishment could be thirty years imprisonment or even the death penalty.

Aspects of the Espionage Act and of the Sedition Act of 1918, which later amended it, sought to stifle any criticism of the government or the war and allowed the Postmaster General to intercept mail containing such criticisms. These acts were controversial, as they clearly infringed upon Americans’ First Amendment right of free speech.

The more restrictive Sedition Act was repealed in December 1920, but not before federal prosecutors brought charges against more than two thousand individuals for alleged violations. The Espionage Act is still in existence and has been the grounds for prominent espionage convictions throughout the last century, including:

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg: After spying for the Soviets during World War II, including passing secrets about the development of the atomic bomb, the Rosenbergs were convicted of espionage in 1951 and, in 1953, became the only American citizens ever executed for the crime.

John Walker: As a Navy Chief Warrant Officer, Walker sold U.S. cryptographic material to the Soviets for nearly two decades, providing his handlers with access to communications and sensitive information that would have largely neutralized U.S. naval forces in the event of war. He was convicted of espionage in 1985.

Aldrich Ames: The CIA officer spied for the Soviets and then the Russians for nine years. His betrayal led to the death of nearly a dozen Soviet intelligence officers who passed secrets to the United States. Ames was convicted of espionage in 1994.

Robert Hanssen: The FBI special agent spied for the Soviets and Russians for more than two decades, and numerous Soviet agents who spied for the United States were killed because of his espionage. He was convicted of espionage in 2001.