Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on audm

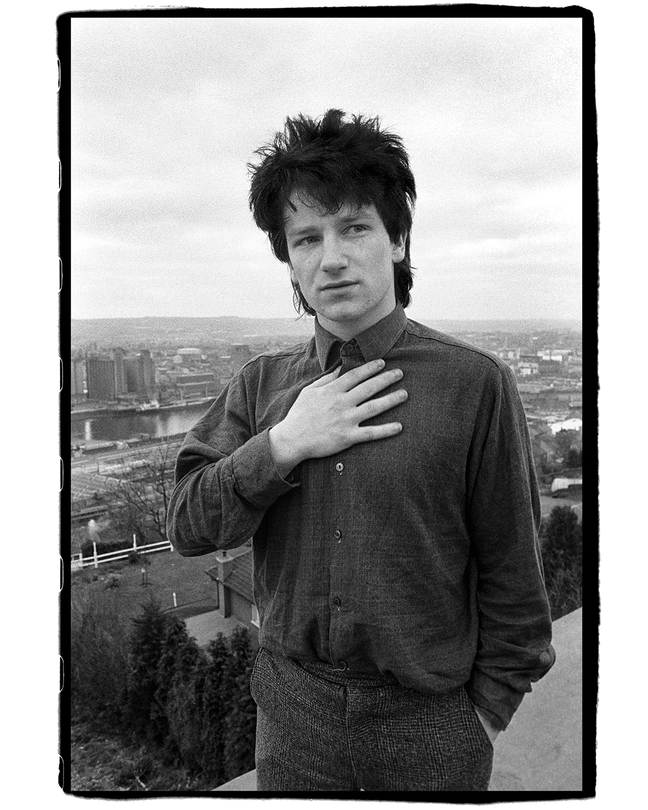

Bono was 14 when his grandfather died. His family was at the cemetery burying him when his mother, Iris, fainted. His father, Bob, and older brother, Norman, took her to the hospital to have her checked out, and Bono went over to his grandmother’s house, where the family was gathering.

A little while later, one of his uncles burst in, wailing: “Iris is dying. Iris is dying. She’s had a stroke.”

It was at that instant, Bono says, that his home disappeared. A hole opened up within him. Bono is now 62 and reflecting on how many rock stars lost their mother at a crucial age: John Lennon, Johnny Rotten, Bob Geldof, Paul McCartney—the list of the abandoned goes on and on. Their mothers’ deaths left them with this bottomless craving. “People who need to be loved at scale, with 20,000 people screaming your name every night, are generally to be avoided,” Bono says with a laugh. “My kind of people.”

His mother lingered on for a few more days after the stroke. Bono and his brother were ushered into her hospital room, and they held her hands while the machine keeping her alive was flicked off.

Then Bono, his father, and his brother returned home and almost never spoke of her again. They barely even thought of her, at least for years. “It’s not just she’s dead; we disappeared her,” Bono says.

His father sunk into his opera. He would stand in front of their stereo, surrounded by the strains of La Traviata, lost to the rest of the world. Bono would watch him, unable to get to him. “He doesn’t notice that I’m in the room looking at him,” Bono writes in Surrender, his entrancing new memoir.

They no longer had a home, just a house. Bono blamed his father for his mother’s death. “I didn’t kill her; you killed her, by ignoring her. You won’t ignore me,” is how Bono puts it in the book. The three men who used to scream at the TV now scream at each other. Their passions are operatic. Bono’s living off cans of meat and beans and these little pellets of mush that turn into a kind of mashed potato when boiled. During these years he is drowning, clutching at anything to survive. His self-confidence drains away. He starts struggling in school. He wants to feel special, but there’s no evidence that he is. He desperately yearns to have his father pay attention to him. He finds he can win that attention only when they argue and when they play chess together. He can’t get his father’s attention unless he beats him at something.

His father had a beautiful tenor voice, but he protected himself from disappointment by not allowing himself any dreams about a musical career—and then his great regret in life was that he didn’t have the courage to try to pursue one. No wonder music would be exactly the thing Bono would want to go into, to succeed where his father didn’t, to make his father see him. “There’s a little bit of patricide” in the book, he admits to me. “If you ask yourself the question How would you take this man down? the answer would be, Become the tenor that he wished to be. Of course!”

Years later, Bono’s musical dreams all came true. But his father remained permanently irascible. One night U2 was playing a big arena in Texas and Bono flew his father to America, where he’d never been, to watch the concert. After the show, his father came backstage, looking emotional. Bono thought something profound was about to happen—the father-son connection he’s been waiting for all of his life. His father stuck out his hand. “Son,” he said, “you’re very professional.” He’d hit the limits of what he could express.

For Bono, getting in touch with his mother became a middle-age quest. When U2 was starting out, they rehearsed in a cottage built into an outer wall of the cemetery where his mother was buried. Bono worked on a song called “I Will Follow,” about a boy whose mother dies. The boy is telling her he will follow her into the grave. It never occurred to Bono that this song might be autobiographical. It never occurred to him to visit the grave of the woman who was lying about 100 yards away from where he was singing; he didn’t even think of her. “That’s the thing about sublimation. It’s almost the farthest we go to bury who we are,” he says now with some wonder.

Not until three decades later did he finally face her absence and what it did to him. In his 50s, he was able to write the lyrics for a song called “Iris (Hold Me Close).” One of them goes: “The ache / in my heart / is so much a part of who I am / Something in your eyes / took a thousand years to get here.”

I tell you all of this because there is something about him I’m trying to understand—I’ll call it his “muchness.” There is just a lot to the guy—so much driven intensity; so much sensitivity, anger, joy, and propulsive energy. If you watch U2 perform, you see three guys playing their instruments in a cool, understated way, and then this short, crazy Irishman climbing frantically around the stage. Spend any time with him offstage, and he is fantastically entertaining, filling every room with stories and argument. He’s a maximalist at nearly everything he does.

Musically and in his activist life, Bono exhibits a pattern of overreaching, his lofty goals sometimes exceeding his grasp. One grand project after another—gigantic concert tours, economic development in Africa, addressing the AIDS crisis. (Fighting AIDS and global poverty are his two biggest causes.) Years ago, he was a guest columnist for The New York Times. I used to tell him, “It’s not ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday.’ It’s just a column. Keep it pointed and prosaic.” I think he had trouble adjusting to the concept.

Some people find his muchness annoying and pretentious. He says that people are frequently telling him, “Just cool your jets, man. Just chill the fuck out.” But as he writes in his book, “It’s hard for me to turn myself off.”

Where does all of this come from?

One theory is that the fusion reactor within him was produced by the traumas of his youth. He’s yearning to fill the holes—the death of his mother, the absence of his father. By this theory, the story of Bono is one of scarcity, the story of the lifetime he’s spent trying to find the love that was ripped away.

Bono himself seems to accept this theory. Success is an “outworking of dysfunction,” he argues in the book, “a reward for really, really hard work, which may be obscuring some kind of neurosis.”

But people who operate out of a scarcity mindset usually have their resentments on full display. As far as I can tell, Bono doesn’t have a resentful bone in his body. Scarcity people never seem fully happy no matter how much they achieve. Bono is generally happy, energized, enthusiastic.

So perhaps the source of Bono’s energy and unrelenting drive may not be scarcity, but abundance. The guy had a rotten childhood, but since then he has been blessed with just about everything life can offer. Perhaps he is simply manically excited to take advantage of it all.

While I spent a few days with him in Dublin this fall, an old book came to mind. It was an analysis of American culture called People of Plenty, by the late historian David Potter. The core argument made by the school of historians Potter belonged to is that America’s natural character is defined by abundance. The European settlers who first came to the country found forests stretching on forever, flocks of geese so large that they required 30 minutes to take off. All of this possibility drove the settlers sort of mad. They found themselves walking more in a day than they had ever imagined, dreaming dreams bigger than they had ever imagined. These immigrants, the ones who weren’t brought here in chains, turned entrepreneurial, disordered, antic, religiously zealous, morally charged, messianic, and perpetually restless. They measured their life by how much they had grown and how far they had climbed. They were propelled by a central contradiction: They had this intense spiritual drive to complete God’s plans for humanity on this continent—and they also had this fevered ambition to get really rich. They were propelled by a moral materialism that would never let them rest.

One day I was riding around Dublin with Bono in a tiny Fiat, and the thought occurred to me: Bono’s a little like that. He may be Irish, but he’s got a lot of that loud, American, go-go type in him—part messiah, part showman.

We are sitting in Mount Temple, the school he attended during his teenage years. It is as generic and tattered a building as you can imagine, walls of cinder block painted bright colors. It was built by the World Bank at a time when Ireland was still the kind of poor country that depended on the World Bank.

Bono shows me the bulletin board where Larry Mullen Jr. tacked the notice that read Drummer seeks musicians to form band—the notice that produced U2. Bono shows me the music room where U2 first practiced together. It’s just a bunch of high-school chairs and desks with a metal case for instruments in the back and a beat-up piano in the front. Bono plays me a snippet of a Sinatra song.

“Something happened here,” Bono says. “Something was going on.” It certainly was and it certainly did. You can source Bono’s life to the psychic loss of his parents, or you can source it to what came next. Bono may have been a basket case at 14, but by 18 he had found the five people whom he would spend the rest of his life with—Jesus Christ; his wife, Ali; and his bandmates, Mullen, Adam Clayton, and David Evans—and he met them all at this school. He joined his band and started dating his wife in the exact same week. For a teenager who seemed to be drowning, he did a fantastic job of finding companions for life. Who manages to do all that by age 18?

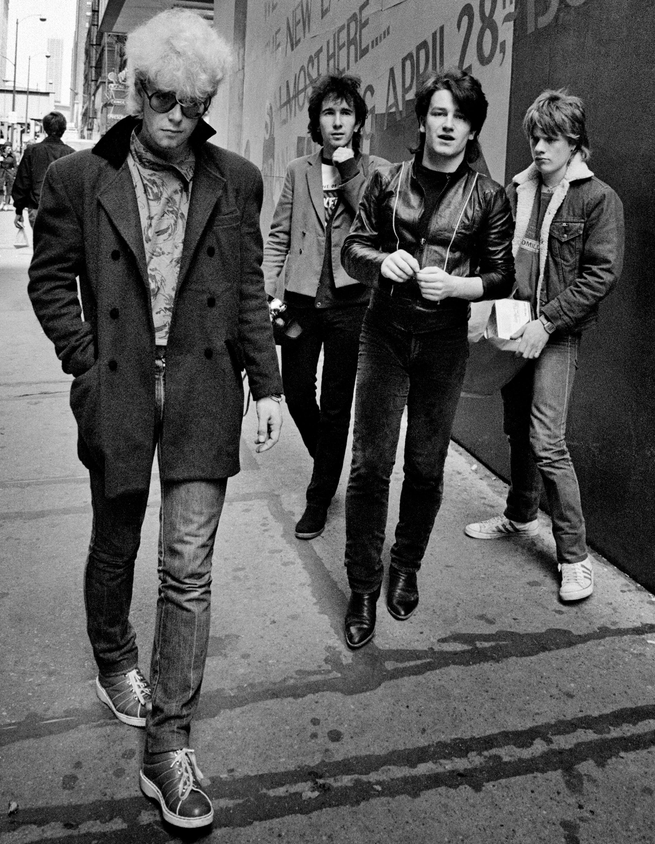

This was in the mid-1970s, the age of the Ramones and the Sex Pistols, the high-water mark of punk rock. Bono and his gang were punk rockers. They wore kilts and bomber boots, mohawks and buzz haircuts. At some point in high school, they came across this radical Christian group called Shalom. Bono’s father was Catholic, and his mother had been Protestant, and he wanted nothing to do with the Church, or the vicious tribalism that was hurtling Ireland toward civil war. But this fringe Christian collective was different. Its members were suspicious of materialism. They put the poor at the heart of their faith. Their Jesus was this badass Jew who took on the establishment. “They lived like first-century Christians,” Bono recalls. “And we thought: That’s pretty punk. And they seemed to accept who we were. We thought, Wow, this is great.”

I ask him, wasn’t becoming Christian in the 1970s kind of uncool? “We were on a whole other level of uncool. We genuinely thought cool was uncool.” Bono’s point is that you can’t experience God while being cool—it takes pure abandon, the raw act of exposing yourself. That, he explains, is what makes faith like rock and roll.

Bono scrambles our categories. We’ve all inherited a certain culture-war narrative over the past 50 years. Rock and roll is on one side, along with sex, drugs, and liberation. Religion is on the other side, along with judgmentalism, sexual repression, and deference to authority. But for Bono, Mullen, and Evans—the U2 members who became and remain Christians—punk rock and the radical Christ are on the same team. (Evans became known as The Edge. Bono, born Paul David Hewson, was given the nickname that eventually became his stage name—shortened from Bono Vox of O’Connell Street—by his best friend since childhood.) The three of them embraced a faith that simply bypassed the encrustations of 2,000 years of religious civilization and returned straight to Jesus: the helpless baby who was born on a bed of straw and shit; the wandering troubadour who put the poor, the marginalized, and the ailing at the center of his gaze; the rebel outsider who confronted the power structures of his society and took them all on at once. This alternative form of Christianity is something that, say, American evangelicals could have adopted. But mostly they did not.

The boys formed their band, went through the hard apprenticeship of rejection that all teenage bands go through, and then finally got to make an album, Boy. Most rock albums, especially in those days, were about rebellion, coming of age, savvy knowingness, but this was an album about innocence, about seeing with the eyes of a child. U2 was announcing that the band was going to be in this world, but not of it.

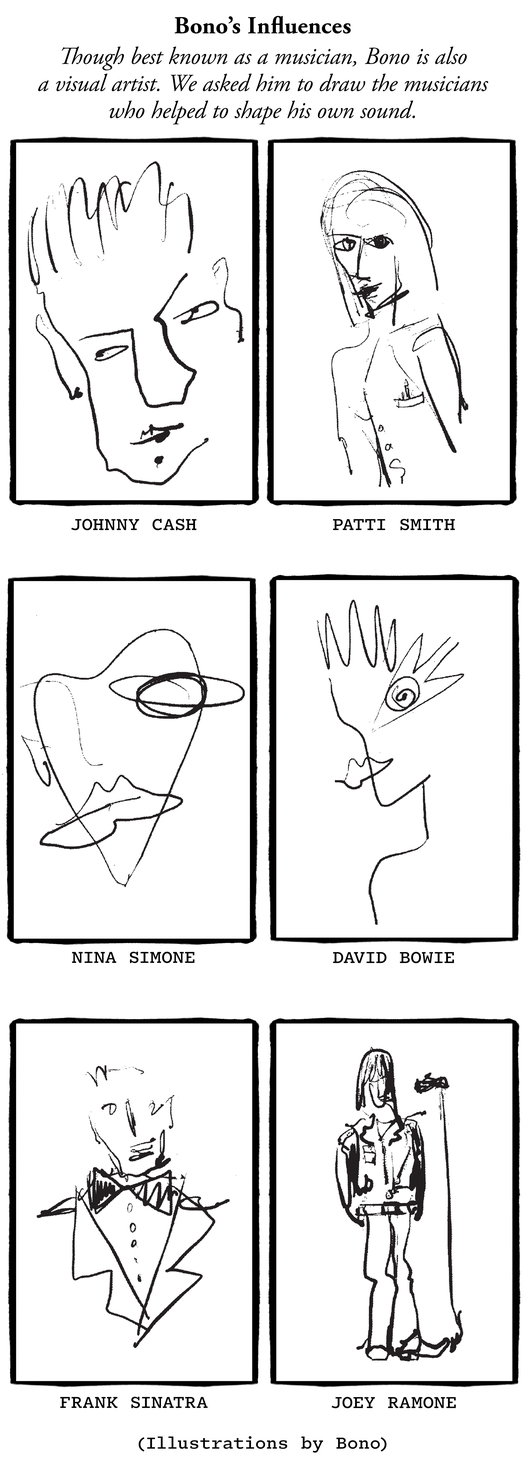

From that first album, U2’s strengths were evident. “Where others would hear harmony or counterpoint,” Bono writes, “I was better at finding the top line in the room, the hook, the clear thought.” Through the next couple of decades, the band turned out hit after hit, and although Bono is always saying how punk he is, I just hear popular, mainstream rock: “With or Without You,” “Where the Streets Have No Name,” “Beautiful Day.”

The band’s other great strength is the pseudo-religious power of their concerts. Bono was influenced by an obscure book called The Death and Resurrection Show: From Shaman to Superstar, by Rogan P. Taylor, which argues that modern performance culture has its ancient roots in shamanism. When we go to a concert, we enter the presence of a mystic who interacts with the spirit world and brings spiritual energies into the physical one. “We’re religious people even when we are not. We find ritual and ceremony powerful,” Bono says. “We were always interested in the ecstatic. I think our music reflects that.”

Boy was a success, and the band was on its way. But then The Edge, the lead guitarist, declared that he needed to quit. He told Bono he didn’t see how they could be both believers and in a band. He didn’t see how they could be global stars and fulfill the humbler “calling to serve a local community.” The world was so broken and needed love; what good could a few songs do? Bono, experiencing some of the same doubts, replied, “If you’re out, I’m out.”

Their manager, Paul McGuinness, who had just signed a bunch of contracts for their coming tour, was astounded. “Am I to gather from this that you have been talking with God?” he asked skeptically. Yes. “Do you think God would have you break a legal contract?”

But it was something else that really kept the band together. The Edge began to write “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” calling for an end to sectarian violence in Northern Ireland. With that song U2 saw how rock could be not just an expression of what was going on in their lives, but a vehicle to help heal a broken world. They would be missional or not at all.

The band stayed together, but the tension The Edge identified has never gone away. How do you reconcile the humility of faith with the egotism of superstardom, the purity of the Holy Spirit with the material excess of show business, the drive to achieve musical greatness with the posture of surrender to grace?

Bono’s memoir can be read as a spiritual adventure story, a Pilgrim’s Progress with superyachts and supermodels (or as Bono jokes, “The pilgrim’s lack of progress”). On the one hand, it is called Surrender, and this act of surrendering himself to a higher love remains a guiding hope in his life. “I’d always be first up when there was an altar call, the ‘come to Jesus’ moment,” he writes in the book. “I still am. If I was in a café right now and someone said, ‘Stand up if you’re ready to give your life to Jesus,’ I’d be first to my feet. I took Jesus with me everywhere and I still do. I’ve never left Jesus out of the most banal or profane actions of my life.”

On the other hand, he also walks around with the most gargantuan worldly ambitions burning in his chest. From the beginning, Bono wanted U2 to be like the Beatles and the other great bands. “Megalomania started at a very early age,” he jokes. “It’s unbelievable. God almighty.” All these decades, Bono and his bandmates have been relentlessly chasing the perfect rock-and-roll album, the perfect show. He now admits this often made him impossible. Throughout the years, Bono insisted that U2 produce a new sound with every album, as the Beatles had. In the book he describes U2’s creative process in great detail, and it’s basically a series of scenes in which Bono is haranguing his mates: “Too familiar!” “Making a band, breaking a band, remaking a band.”

This grand ambitiousness has meant that they’ve taken a lot of musical risks, not all of which have paid off. Or as Bono puts it in Surrender, “Our best work is never too far from our worst.” During one reinvention moment he asks himself, “Why would I put everything at risk again? What’s got into me? What gets into me?”

I ask Bono about his core motivator. Is it the quest for achievement, for intimacy, for fame? “I’m ‘I don’t want to blow it’ motivated,” he says. “I’ve got these incredible opportunities and I don’t want to blow it.” He emails me a few days later to make the point that the enemy of greatness is not crap; the enemy of greatness is “very good.” You have to hammer, exhausted, through “very good” to get to greatness.

This ferocity is often hard on those around him. One day Bono worked himself up into such a rage that The Edge had to punch him on the side of the head. “The friendships in the band have been ins and outs for sure,” Bono says. “I have been insufferable at times. Pushing them and prodding them. Not wanting to blow it.”

I ask him whether the rage he keeps talking about is against only the injustices of the world, or also directed at the people he loves. “Both, sadly,” he says. “And I’ve had to apologize to my bandmates for the hectoring they’ve received over the years.” Has he brought his rage home to his family? “I have lost my temper a few times as a father.” (He has four children, all adults now.) “And that has brought me deep shame. But I’m that guy. I’m a bit wound up.”

The band’s worldly ambitions paid off in the most spectacular way. By the time U2 was rich and famous, Bono had entered the lofty height of celebrity—a life that doesn’t look much like the radical simplicity of the first-century Christians. He’s got a villa in the south of France. He’s friends with Christy Turlington and Brad Pitt. One time he was at a small White House dinner party with Barack Obama and, after an allergic reaction to some red wine, he left the table in the middle of the meal to take a nap in the Lincoln Bedroom. Another time Mikhail Gorbachev showed up at his front door in Dublin carrying a giant teddy bear. And another time he thought he’d peed his pants while sitting on Frank Sinatra’s couch. The stories in the book can be sidesplitting.

Bono’s social energy is on par with all his other kinds of energy, and as he speaks you realize the guy knows everybody—Bob Dylan, Pavarotti, Billy Graham, and Larry Summers; the pope, George W. Bush, Allen Ginsberg, and Quincy Jones. He’s so famous himself, he’s not name-dropping; he’s just thrilled to meet people. I have a theory that celebrities love to hang out with one another because deep down, they are still the sad outsiders they were in high school, and they’re thrilled that these cool people want to hang out with them.

Rowing for heaven by day and drinking with superstars by night—Bono’s spiritual adventure is the greatest high-wire act in show business. You can’t help wondering which way he’ll go. Will he be ruled by his rage or his compassion? Can he find inner stillness amid the raucous go-go of his life? Can he keep his focus on the celestial spheres when the people on the beach at Nice are so damn sexy? Can he die to self, or has his permanent tendency toward self-seriousness and pomposity become too great? If the guy is so concerned with his soul, why did he spend so much time writing about his hair? The ultimate questions at the center of it all are the same ones that have haunted American history: Can you be great and also good? Can you serve the higher realm while partying your way through this one?

Three things save him. The first is his wife, Ali. She is the star of the memoir, light and warmth, solidly grounded, deeply souled. Ali’s the one who tells him when he’s becoming too self-serious and losing his sense of mischief. She’s his emotional foundation and spiritual partner. “Ali will let her soul be searched only if you reciprocate and she is ready for the long dive,” Bono writes. “Best to arrive at her fort defenseless to have half a chance at challenging her own unbroachable defense system.”

Their home near Dublin has a gigantically long kitchen table made from a tree trunk that hosts dinners of 20 to 30 people, with dancing, drinking, and arguing about world affairs past 1 a.m. The place has the spirit of the perfect Irish pub. “It turns out I’m oriented toward horizontal relationships rather than vertical ones,” he says. His home is communal. His band is communal. His philanthropic work is communal. His life is rooted in peer relationships.

The second thing that saves him is his activism. About a decade ago, I went to a U2 concert. As I drove home, one of Bono’s people called me and asked if I wanted to hang out with him at his hotel. This is my dream: hanging out with a rock star after a concert. I got to the hotel bar and there was Bono, an archbishop, some World Bank economists, and a West African government official. We ended up talking about developing-world debt obligations until early in the morning.

Celebrity activists are in bad odor these days. Who cares what privileged superstars think? Bono has certainly fallen into many of those traps, but he is also a celebrity activist like no other. He knows who the deputy national security adviser is. He knows who the staff on the Senate Appropriations Committee are. He shows his face not just at large televised events, but in one-on-one meetings lobbying House staffers and mid-level White House officials on developing-world debt relief and money for drugs to combat HIV. “One of the greatest characters in my life over the last twenty-five years has been the capital city of the United States of America,” he writes.

He may be a mystic shaman on the concert stage, but his view of social change is unromantic; he knows that it starts with relentless pressure. (One day Bono was haranguing George W. Bush because AIDS medications weren’t getting to Africa fast enough. Finally, Bush interrupted him: “Can I speak? I am the president.”) It’s about long, tiring negotiations and compromise—stale coffee and, as he puts it to me, “damp cheese plates, soggy sandwiches late at night.” And it’s about rejecting fundamentalism in all its forms, religious or ideological. Stay flexible; make constant, steady progress.

Bono has been ruthlessly single-minded. He will meet with anybody who can help those causes, no matter how noxious to him they might be on other subjects. The most famous example is his successful campaign to woo Jesse Helms to support aid to Africa.

In Surrender, Bono relays a story, told to him by Harry Belafonte, that explains his methodology. When Bobby Kennedy was appointed attorney general, the civil-rights community was deeply suspicious of him. Martin Luther King Jr. hosted a meeting where the other leaders trashed Kennedy as an Irish redneck who would set back civil rights. King slammed his hand on the table and asked, “Does anyone here have anything positive to say about our new attorney general?” No, that’s the point, the others said; there’s nothing good about his record. King responded, “I’m releasing you into the world to find one positive thing to say about Bobby Kennedy, because that one positive thing will be the door through which our movement will have to pass.” They found that RFK was close to his bishop—and through that door they converted him into a great champion for civil rights.

Bono is often teased about his activism—I’m going to save the world, and I don’t care how many magazine covers I have to be on to do it. But this work has been a useful unfolding of his faith. “Your faith is an action,” he tells me. Preach the Gospel, but only use words if absolutely necessary. His activism has been the way he can take the fame life gave him and turn it into a useful currency. “While I hope God is with us in our mansions on the hill or holiday homes by the sea,” he writes, “I know God is with the poorest and most vulnerable.”

His activism has also connected him with one of his enduring loves: America. At a time when many of us Americans feel a sense of national decline, Bono has a bracing alternative view. “America might be the greatest song the world has yet to hear,” he told an audience of Americans at the Fulbright Association in March. “It’s an exciting thought that after 246 years of this struggle for freedom, after 246 years of inching and crawling towards freedom, sometimes on your belly, sometimes on your knees, sometimes marching, sometimes striding—this might be the moment you let freedom ring.”

The third thing that has saved him has been his holy longing, or, as he might put it, God’s longing for him. Bono’s soul is perpetually aflame, and this drives him forward, nurtures his growth and his heavenly aspirations.

Bono has reached a point where he feels grateful for his father. In Surrender, Bono paints a warm, sympathetic portrait of the old man—who was in his own way a charming, talented guy who suffered a loss he could not process, who had his 14-year-old son coming at him with “guns blazing.”

These days, Bono—this noisy and garrulous man—craves silence. He points out that Elijah had to go to the cave to hear God, and God was heard not in the thunder and the wind but in the sound of silence. All of his life, he has reinvented himself. Now he thinks it may be time to do it again. “Music might be a jealous God. It was always the easiest thing for me. I wake up with melodies in my head,” he says. “But now I feel more like: Shut up and listen. If you want to take it to the next level, you may have to rethink your life.”

What does that look like? “The flag of surrender has come around again for me.” What does surrender mean exactly? “It’s just out of my reach. I’m getting to the place where I do not have to do, but just be. It’s trying to transcend myself. It’s like my antidote to me. The antidote to me is surrender.”

The ending of his book is a beautiful evocation of peace—a riotous man’s homage to stillness. He writes the book in lyrics, not paragraphs: “The wound of my teenage years that had become an opening is now closed / the search for home is now over / it is you / I am home / no longer in exile.” Can a guy like Bono really achieve stillness? Especially when he has so much yet to say?

It’s hard to know the answer to that. At one point he told me that throughout his whole life, he’s been searching for home, and that lately he has come to realize that home is not a place, but a person. I neglected to ask the follow-up question. Is that person Ali? Jesus? Any random soul he happens to be in front of that day? Maybe all of the above.

This article appears in the December 2022 print edition with the headline “Bono’s Great Adventure.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.