In late spring 2023, the Biden administration introduced the Safe Mobility Offices (SMO) Initiative to expand the use of and access to protection and migration pathways closer to home. Arising out of the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration, SMOs (previously known as Regional Processing Centers) aim to provide people seeking safety, security, economic opportunity, and reunification with family access to regularized pathways closer to home. Though not intended to be a substitute for territorial access to asylum, SMOs reflect one modality in a larger strategic shift for how the U.S. — and other countries — can respond to the complex movement of people with protection and non-protection needs so that they do not undertake dangerous journeys northward.

Working with Central and South American countries, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the Biden administration established SMOs to screen and process people for protection pathways. In some instances, this includes referring people to the United States, Canada, and Spain.

As of the end of summer 2023, SMOs are operational in Guatemala, Colombia, and Costa Rica While SMOs provide information on or access to protection and non-protection pathways, there is no one model. Each SMO provides eligibility to different populations under different conditions, a reflection of the bilateral agreement between the U.S. and domestic governments. Just as there is hope to establish SMOs in other countries in the hemisphere, the desire is to grow the number of receiving countries as well.

The Biden administration’s plans for SMOs have been met with mixed reactions. Some have praised the administration for creating a new modality to address the complex movement of people with protection and non-protection needs seeking to enter the United States. Others have criticized the administration for changing access to asylum and failing to first address the root causes of forced displacement and migration.

This paper examines how the evolving nature of migration from the 20th century to today requires a hemispheric response, such as initiatives like the Safe Mobility Offices, to humanely and more effectively manage the movement of people across borders in the 21st century. Although this paper is framed around migration, it addresses how migration trends are actually a reflection of mixed migration imperatives, with people crossing borders for protection needs and other reasons.

Any successful model of migration management should allow individuals to access safe, humane, and orderly pathways worldwide. This will require the type of multilateral strategic approach as envisioned in the SMOS initiatives – and, critically, other modalities too — as part of a larger paradigm shift to humanely and effectively respond to the ever-increasing movement of people across borders.

Changing migration patterns in the hemisphere

The Biden administration has said that SMOs will help to address the growing number of migrants seeking to enter the United States by offering them the opportunity to access or learn of safe and legal pathways closer to home, which will also help protect migrants from exploitation and dangerous journeys northward to the U.S. border.

A helpful way to think about Hemispheric migration in the 21st century is by breaking it down into three stages. While this level of analysis is broad and the stages inevitably overlap, this framework captures the most significant changes of the 21st century.

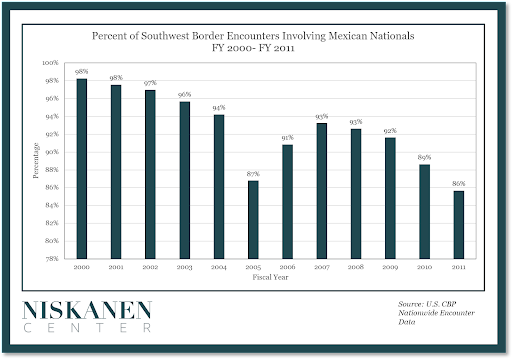

The first stage, which occurred between 2000 to 2011, can be defined by the large share of Mexican nationals migrating via the southern border. According to CBP data, an average of 93 percent of encounters at the southwest border were with Mexican nationals during this period. For comparison, at the time of writing in 2023, only 31 percent of southwest border encounters have been with Mexican nationals.

This first stage is critically important because it establishes an archetype for migration that influences policy today. The first decade of the 21st century solidified long-standing responses tailored to deal with unauthorized migration by single, typically male, Mexican economic migrants. In less tangible ways, this stage has also had far-reaching effects by linking the public imagination of who migrants are with this population.

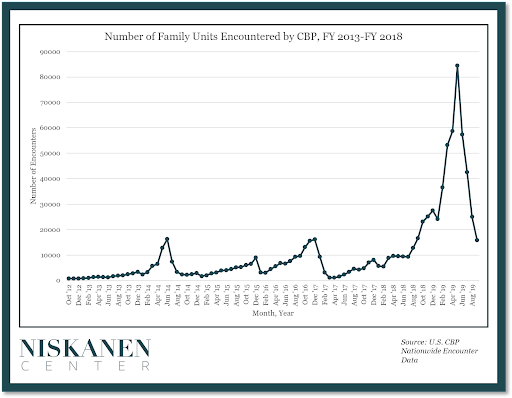

By the early 2010s, however, it was clear that a significant shift was happening at the border. This period — which runs through the present day — marked the beginning of the second stage, defined by the relative decline of migration from Mexico and a rise in migration from the Northern Triangle countries (Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador). Migrants from these countries outnumbered those from Mexico by FY 2014, reaching a peak in FY 2019.

This stage has been notable because the type of migrant arriving at the southern border has changed beyond nationality. Migrants from the Northern Triangle are more likely to flee for humanitarian reasons. In other words, they are more likely to be seeking asylum. They are also more likely to arrive as family units or unaccompanied children, which has added additional strains to capacity at the border, where CBP facilities and processing were designed for single adult males and recast the public debate around migration.

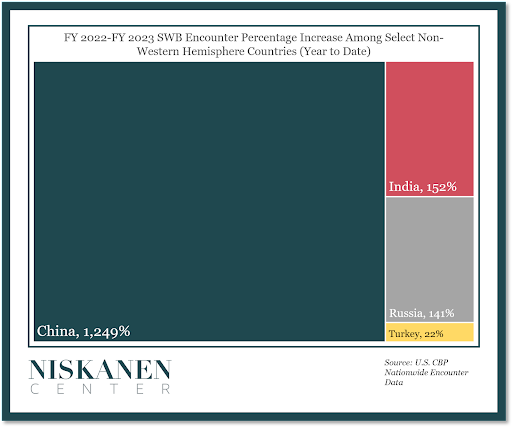

While migration from these countries is an ongoing challenge, other emerging trends are now at the forefront. The third stage, which began in FY 2021 and is still taking shape, is distinguished by the rise of migration from countries U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) deems “historically atypical.” Until 2020 (with a drop to 89 percent), over 90 percent of migrants apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border were from Mexico and northern Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras).

By 2022, however, that share fell to 57 percent. Mexico is still first over the first six months of fiscal year 2023, but Guatemala has fallen from second to fifth, behind Cuba, Nicaragua, and Colombia. Honduras is sixth. El Salvador is 11th, behind Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, and Haiti.

Migration from beyond the Americas also increased dramatically during the Title 42 period. Comparing the first nine months of fiscal year 2023 with the same period in fiscal year 2022, encounters with migrants from Turkey, Russia, China, and India are up with varying degrees of significance.

The reasons behind these shifts are complex. Crucially, they are also unlikely to change soon. While compiling an exhaustive list of factors behind the latest migration trends is a near-impossible task, there are at least seven central factors that help explain the changes at the border and how they may continue in the next decade:

- The economic fallout from the pandemic – While economies in Latin America showed signs of recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, that recovery has since stalled. Indeed, the World Bank has described Latin America’s regional economic performance in the aftermath of the pandemic as among the lowest in the world. Economic factors likely explain why much of the post-pandemic surge at the border has been composed of single adults who are likely seeking work.

- Insecurity – Violence in Latin America remains a widespread and deeply rooted problem. In Mexico, 75 percent of adults did not feel safe where they lived in 2022, a number that has hardly moved for a decade. In Brazil, 64 percent of people reported feeling unsafe when they go out at night. These statistics reflect a grim reality: per capita, eighteen out of twenty countries with the highest homicide rates are in the Americas. Given these conditions, it is understandable why individuals and families are willing to spend considerable resources to try to reach the United States.

- Climate Change and Natural Disasters – Adding to this already grim picture, natural disasters and changes in climate conditions have also adversely impacted the region. The Congressional Research Service identified droughts and hurricanes as significant drivers of migration from the Northern Triangle to the U.S. Crop shortages persist in other parts of the region and will render migration patterns ever more unpredictable.

- Entrenched Unrest and Persecution – It is not a coincidence that a significant percentage of the new migrants at the southern border are from Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. Each of these countries has a long record of political repression, which affords residents few avenues to express dissent without consequences. As a result, many opt for exile instead.

- Accelerating Humanitarian and Political Crises – Haiti faces a catastrophic mix of overlapping crises without easy solutions. Mexico continues to struggle with cartel violence that impacts vast swathes of the country. Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru’s governments are in different stages of political crisis. None of these scenarios are likely to be easily resolved, and if they worsen, each could trigger a mass influx of migrants toward the southern border.

- Family Reunification – New humanitarian parole programs focused on migrants from the Northern Triangle and Colombia and upgraded reunification programs for Haitians and Cubans could also impact how migrants reach the U.S. by allowing migrants with approved, family-based petitions to travel to the U.S. in anticipation of a visa becoming available to them.

- Increased Use of Travel Route Through the Darien Gap – The increasing ability to travel through the once impassible Darién Gap, the region connecting Panama to Colombia, has also changed migration trends as governments have cracked down on migrants’ access to land and sea routes. The journey is still difficult, with non-existent laws, rampant cartel and criminal activity, and challenging weather conditions. Rapes and robberies are common; even a minor injury can prove fatal thanks to the remote location and minimal medical resources. Despite these risks, more migrants have undertaken the journey as the Darien Gap is the only overland route connecting South and Central America.

The failure of deterrence policies

These changing patterns have taken hold despite decades of both U.S. political parties featuring deterrent policies intended to dissuade migrants from reaching the border by imposing penalties on those who do as cornerstones of their approaches to border management. The logic behind deterrence is that by implementing harsher consequences for unauthorized migration, prospective migrants will either opt for different migration channels–or choose not to migrate altogether, given the massive risks.

The appeal of deterrence measures is that they are simple to understand, seem easy to implement, and convey resolve and strength to domestic audiences. Given these incentives, it is unsurprising that deterrence policies have enduring, bipartisan adoption as methods to cope with increasing migrant arrivals. Nevertheless, decades of evidence indicate that deterrence policies have often failed.

For example, President Clinton launched Operation Gatekeeper and Operation Hold the Line in the early 1990s in response to increased unauthorized crossings at the El Paso and San Diego borders. These operations concentrated resources, including convoys and barriers at visible points in the El Paso and San Diego sectors, to signal to unauthorized migrants that these border sections were now heavily manned. It was also thought that increased presence in El Paso and San Diego would force migrants to make longer treks to more distant crossing points, leading to attrition and decreased migration. While apprehensions dropped significantly in the target sectors, apprehensions skyrocketed in the more remote Tucson sector, as did migrant deaths. In effect, migrants were not deterred – they were funneled towards more dangerous routes and crossing points instead. Similarly, the Obama administration’s increased use of expedited removal and detention in 2014 didn’t lead to more apprehensions; nor did it deter arrivals.

Even forcible family separation, the most severe deterrence policy, did little to curb migration. Under this policy, apprehensions of unaccompanied minors and family units increased by as much as 50 percent compared to the previous period. Conversely, one of the Biden administration’s most effective policies in slowing arrivals — Uniting for Ukraine–led to a significant drop in encounters, even though deterrence played no role. One of the more recent examples of a failed deterrence policy is the two-year implementation of Title 42–based on a public health policy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic–that allowed the U.S. to expel asylum seekers. Since its implementation, many prominent organizations and individuals have condemned the public health order’s misuse as a guise for closing our southern border to asylum seekers.

In April 2022, the CDC issued a decision terminating Title 42. The termination was to take effect on May 23, 2022. But in response, the attorneys general of Arizona, Louisiana, and Missouri — and eventually 23 other states — filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Louisiana, Lafayette Division, challenging the Biden administration’s revocation of Title 42. While that lawsuit was ongoing, Title 42 remained in place but eventually became moot. Then, on May 11, 2023, the Biden Administration terminated the COVID-19 public health emergency, thus ending Title 42, which voided the lawsuit.

Since March 2020, Title 42 has been used to expel people from the U.S.-Mexico border over 2.8 million times. Of all migrants encountered at the border since March 2020, 50 percent were quickly expelled, typically to Mexico. Still, Title 42 did little to deter the flow of migration. In 2022, CBP encountered 1.48 million individual migrants on 2.2 million occasions — those numbers are different because the rapidity of Title 42 expulsions eased repeat attempts to cross.

Over time, chronic deterrence policies divert resources from processing and towards apprehension and detention. This creates a cycle where processing capacity is constantly overwhelmed, leading to calls for more robust deterrence measures.

- Understanding why these policies fail to influence migrant behavior significantly can help us develop effective policy solutions. First, the core logic of deterrence policies — that we can dissuade undesirable behavior through punishment — overlooks a fundamental aspect of human nature: our ability to find innovative solutions around barriers, especially when we feel our lives or the lives of our families are at stake. There are no imaginable deterrent measures the U.S. government could take that would be more severe than the conditions the most desperate migrants experience in their home countries.

- Second, the inherently fickle, chaotic nature of decades of U.S. border policy incentivizes migrants to journey north, hoping that unfavorable policies will change. This is compounded by the fact that migrants often operate with limited information and are vulnerable to rumors and misinformation spread by self-interested actors.

- And finally — and perhaps most importantly— is the lack of an alternative legal pathway. For many, seeking asylum or entering unauthorized are the only viable options.

Effective policies should focus on innovating more adaptive, evidence-based approaches that can change how the U.S. humanely and effectively responds to the movement of people across borders whose reasons for migration will continue to evolve, as examined above. As the number of people seeking international protection and migrating due to economic insecurity and poverty, climate change, human insecurity, and other needs continues to grow exponentially, a new strategic framework is needed.

Paradigm shift: Safe Mobility Offices as one modality to manage mixed migration

The introduction of the SMOs reflects a paradigm shift in how the U.S. is approaching mixed migration in the Western Hemisphere. Expanding the number of — and access to — safe and legal pathways for protection and non-protection addresses both humanitarian and national security imperatives. SMOs are one tactic in a multilateral investment in a hemispheric approach to meeting 21st-century needs and challenges to manage mixed migration.