We built a fake metropolis to show how extreme heat could wreck cities

Extreme heat is deadly for humans and not great for infrastructure, either.

Most of the mechanical, electrical and architectural systems we count on every day were built to handle what the climate has always been, not what it is rapidly becoming.

That means, for instance, that Norwegian runways, Seattle streets and London bridges handle wind, rain and cold just fine, but a triple-digit heat wave? Not so much.

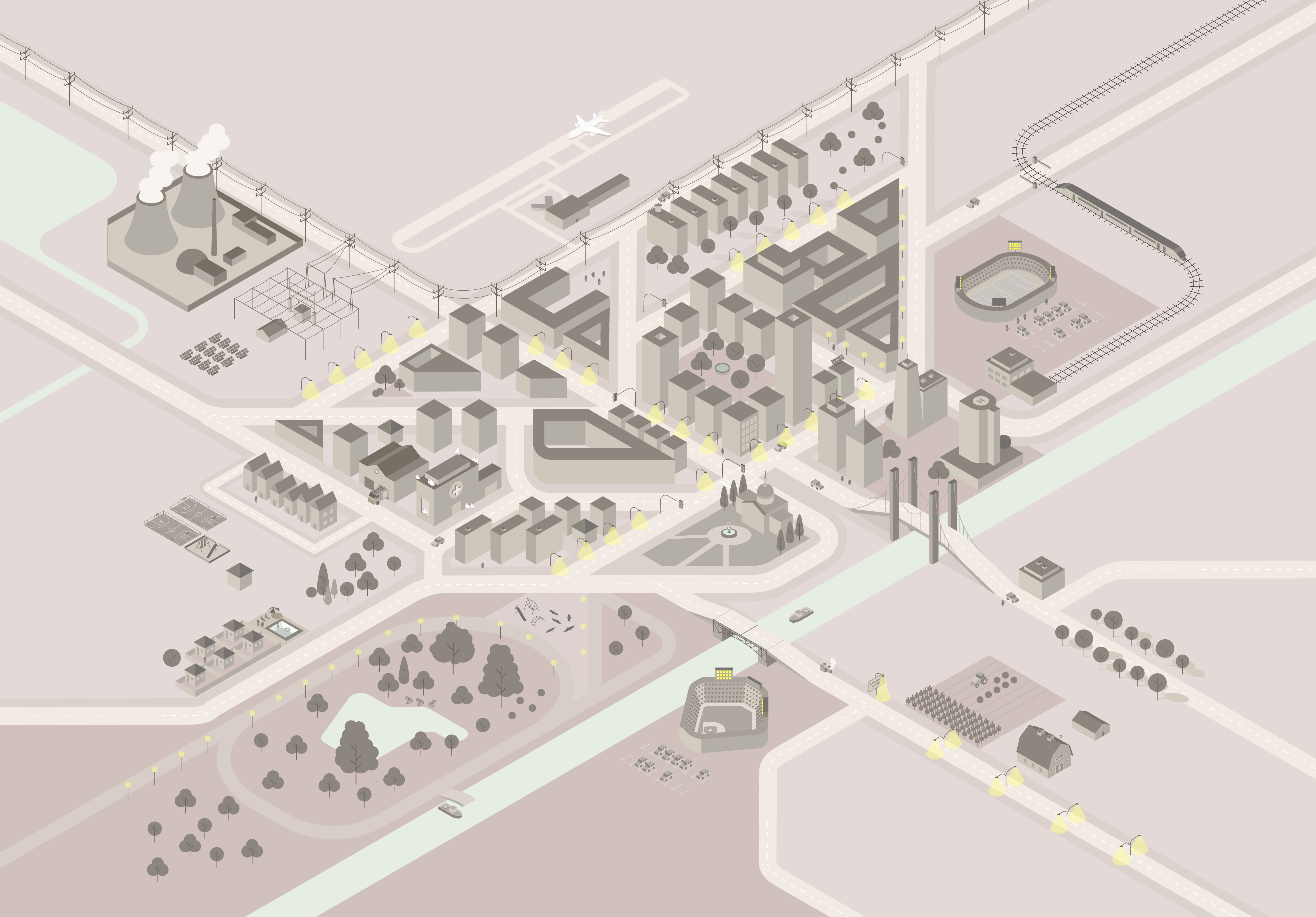

This project illustrates some of what can happen when unprecedented heat settles over a built environment that isn’t ready for it. Each of these things has happened somewhere, or in many places, around the world, but we’re putting them all in one fictitious town.

Welcome to Meltsville. (Wear sunscreen.)

Meltsville summers are usually so mild and evenings so cool that, to be frank, the residents get a little smug about it.

But at the moment, Meltsville is melting.

A monstrous heat dome has settled over the area, and the transportation systems, the power grid, the buildings and even the local colony of bats are all feeling the strain.

[The science of heat domes and how drought and climate change make them worse]

Transportation slows

Many Meltsvillagers immediately tried to get to someplace cooler. But heat causes all kinds of transportation havoc, starting at the airport.

Many of the smaller planes that service Meltsville Regional cannot take off safely in extreme heat, a well-known problem in places such as Phoenix and Dubai. Larger planes can often handle higher heat (and colder cold), but even they may be grounded as temperatures soar toward 120 degrees and beyond.

“The challenge with plane takeoffs during heat waves is not due to airport construction, it’s due to physics,” said Ladd Keith, assistant professor of planning and sustainable built environments at the University of Arizona. Hot air is less dense than cool air, so it provides less lift. Also, heat is bad for machinery: Engines and other components have to work harder. So manufacturers put a hard limit on takeoff temperatures.

It’s just as well that the flights are canceled, because Meltsville’s runways are a bit gooey anyway.

Runway surfaces in hot areas are topped with heat-resistant materials, but traditionally cooler places often use more viscous coatings that are durable in cold weather. Unfortunately, that top layer can soften or even liquefy if the area gets scorching heat.

The same thing happens to roads.

Road builders tailor materials and techniques to the soil, topography, expected usage and, of course, climate. In areas that get both cold and hot weather, they use resilient materials that can handle the yearly swings from one to the other. But those materials may not fare well in an extreme bout of either.

Roads (and sidewalks) that are made of long concrete slabs can expand too much, buckle and crack. Some asphalt can get so soft that heavy trucks and buses sink in and create deep ruts.

Surfaces that have weathered years of cold may become brittle, crumble and flake, while other top coats can melt or burn off, exposing what’s below to more damage.

Even pothole repair can become a headache in the heat, as drivers around the Seattle area learned during the scorching Pacific Northwest heat wave of 2021. Overnight air was too hot to cure the filling material, so when drivers rolled over the repaired spots, clumps of rock and goo rolled up around their tires.

Roger Millar, Washington’s secretary of transportation, said the state’s highway system didn’t have too many other problems: a buckled slab on an interstate highway, a failed drawbridge motor, electronic messaging signs that lost power. “But the thing about our transportation system is you don’t have to have a lot of problems to have a lot of impact.”

When Meltsvillagers repave their roads and runways, they will consider a lighter, more reflective surface that will absorb less heat. They’ll tweak joints that connect concrete slabs to allow more room for expansion.

Perhaps they’ll someday use a “sunscreen for roads,” which Keith said is a type of asphalt rejuvenator that is now being tested in Tucson.

Sunscreen for bridges isn’t a thing yet, but workers in London made a DIY version by wrapping the Victorian-era Hammersmith Bridge in protective foil to try keep cracks in its cast iron from expanding during the brutal July 2022 heat wave.

In this extreme heat, our world-leading Hammersmith Bridge Restoration Project engineers are using a pioneering...

Posted by Hammersmith & Fulham Council on Wednesday, July 13, 2022

Most bridges are not made of cast iron, but many in the United States are in poor condition, according to the National Bridge Inventory.

[With extreme heat, we can’t build roads and railways as we used to]

“As you have a heat wave occurring, it will expand the asphalt, it will expand the steel,” Keith said. “If you already have a poorly rated bridge that needs to be replaced, all of those additional stresses are, quite frankly, a little bit terrifying to think of.”

Meltsville’s trains also run on steel, but not all steel is the same. Rails made for lower temperature thresholds can warp and bend in the heat. On the trains themselves, electrical connections can overheat, and insulation around them can melt.

Even the risk of heat damage is enough to cause operators to slow trains or stop them altogether, which can leave riders waiting longer than usual on sun-exposed platforms.

Meltsvillagers resign themselves to staying home, and those who never thought they would need cooling begin to Google “super-fast AC installation near me.”

The power grid strains

The sudden power demand of all those air conditioners running full blast began to cause big problems over at the Meltsville Nuclear Power Plant.

Power is probably the only infrastructure in which both the supply and the demand are significantly affected by heat, said Mikhail Chester, a professor of civil, environmental and sustainable engineering at Arizona State University whose work focuses on heat and infrastructure preparedness.

“You’ve got to supply the amount of electricity that is being demanded for air conditioning effectively, and at the same time, the system is compromised in a number of ways,” he said. Thermoelectric plants, which include coal, nuclear and some natural gas plants, are compromised the most.

First, if either the water entering the plant or the outside air temperature is warmer than usual, the plant becomes less efficient, Chester said. “Basically you’re going to be generating less electricity from the same lump of coal at the end of the day.”

Nuclear plants need more water to cool the reactors when the water is warmer, which can exacerbate strain on the water supply in addition to forcing operators to scale back production.

And the water discharged from many plants often has to be below a certain temperature to avoid running afoul of environmental regulations.

Even solar panels that dot some of Meltsville’s roofs lose a small fraction of a percent of efficiency in very hot weather.

Then, there are the lines that deliver the power.

Power lines sag when high demand means extra electricity is running through them and generating extra heat. If they droop dangerously close to trees, buildings or other things below them, the power company has to throttle back the amount of electricity to those lines.

The transformers and substations also sustain more wear and tear.

“Stuff just breaks more when it’s hotter,” Chester said. “And that’s for a million reasons. Electronics break more, circuits cut out more. Everything just breaks more frequently.”

All that heat stress pushed the Meltsville power grid closer and closer to its breaking point.

Worried officials institute a series of controlled, rolling blackouts in an attempt to keep the system from failing.

A complete power grid failure in the real world can be catastrophic because unlike a small or planned outage, people cannot just go to the next neighborhood to cool down, and the outages can last for days or weeks. A house with no air conditioning can become an oven, especially for elderly people. When Hurricane Ida knocked out power in Louisiana in 2021, more people died from the heat than had died in the storm.

Buildings overheat

While their AC sat idle for a few hours, a few Meltsvillagers in one neighborhood heard a commotion and stepped outside into ankle-deep water from a burst water main.

Water pipes break more frequently than normal in very hot and very cold weather, and the land around this one dried out and shifted just enough to cause a break. Old, brittle cast-iron pipes are especially susceptible to temperature extremes.

With cooler feet but heavier hearts, the residents trudged back to their homes, and a few of them gasped as they saw warped and melted vinyl siding hanging forlornly from the exterior. The vinyl, so easy to power wash if moss or algae grows during the rainy season, may need to be replaced with a heat-resistant version.

This was all a wake-up call, and Meltsvillagers began to look critically at their homes from a sweltering new perspective.

An awning would be nice, they thought, squinting. Those heat-absorbing black roofs could be replaced with lighter-colored, solar-reflective shingles, or in a pinch, painted white.

And the big south-facing windows, placed perfectly to let in maximum sunshine, could use some retractable blackout shades or at least a few temporary tarps.

Nature struggles

Meltsville has some artsy engineered shade, which spares a few pedestrians from the heat here and there. But most residents moseyed toward the town’s biggest swath of green space, Toasty Critters Park, where huge old trees offered reliable protection from the sun. They arrived to find yellow tape and sweaty city officials, who had just closed some of the shadiest spots because they feared heat-stressed limbs would break off and fall — the same reason some Madrid parks close in high heat.

[As temperatures rise, industries fight heat safeguards for workers]

Just as one of the officials, a landscape planner, remarked that he would research vegetation that thrives in a warmer climate, a lone, sluggish bat wobbled to the ground.

They suddenly realized the local colony was not faring well. After a November 2019 heat wave in northern Australia killed a third of one species of foot-long bat that lives in urban areas, parks began installing misting systems to cool them.

Meltsvillagers did the best they could, pulling out hoses just in time to save the bats, and they sprayed down the playground equipment while they were at it. Every kid who grew up with a metal slide in the neighborhood silently gave thanks.

[Europeans shocked by ‘heat apocalypse’ as temperature records fall]

Our fictional friends in Meltsville had just one weather crisis to handle, with no water shortage, no wildfires, no storms.

But out in the real world, an extreme heat wave is often part of a catastrophic spiral. It may exacerbate drought that parches foliage, which fuels wildfires, which leave barren land susceptible to flooding. Infrastructure that ices over in January may become waterlogged in April and bake in July.

“There’s a concept in engineering called stationarity, the assumption that your assumptions don’t change,” said Millar, a former transportation engineer and planner. “With climate change, those assumptions are changing.”

Additional development by Garland Potts and Junne Alcantara.