AP / Rodrigo Abd

Dig

AP / Rodrigo Abd

Dig

Chile’s Utopia Has Been Postponed

Journalist Marc Cooper, Salvador Allende's former translator, returns to Chile to probe what has and has not changed in 50 years and why its new leftist millennial government is having such a hard time. A Dig curated by Marc CooperThe Other 9/11: A Ghost Story

Fifty years after the coup, Pinochet’s legacy continues to haunt Chile. A man holds a flag with the portrait of late Chile's president Salvador Allende in front of the east side entrance of La Moneda presidential palace, referred to by it's street address, Morande 80, in Santiago, Chile, Thursday, Sept. 11, 2014. The coup toppled Chilean President Salvador Allende and began the military dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet. Allende used the side door to enter and leave the palace. It was also through this door his body was carried by soldiers and firefighters from the destroyed presidential palace after the coup. (AP Photo/Luis Hidalgo)

A man holds a flag with the portrait of late Chile's president Salvador Allende in front of the east side entrance of La Moneda presidential palace, referred to by it's street address, Morande 80, in Santiago, Chile, Thursday, Sept. 11, 2014. The coup toppled Chilean President Salvador Allende and began the military dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet. Allende used the side door to enter and leave the palace. It was also through this door his body was carried by soldiers and firefighters from the destroyed presidential palace after the coup. (AP Photo/Luis Hidalgo)

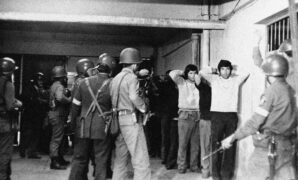

Ahalf-century after his military coup immolated 150 years of Chilean democracy, the ghost of Gen. Augusto Pinochet continues to roil and divide the Andean country he ruled for 17 years. His legacy of human rights abuses and neoliberal economics can be seen in Chile’s extreme inequality, its unreformed and unaccountable military and police, and unresolved human rights abuses, including the fate of more than 1,000 people who were disappeared during the dictatorship and thousands more still awaiting the trial of their abusers. While there has been uneven progress in these areas since Pinochet ceded power in 1990, many features of his dictatorship remain enshrined in the 1980 constitution that Chile’s new government is attempting, and struggling, to replace. The most nefarious part of that charter is its favoring of private industry to run crucial services like education and social security. “We are trying to build a future, but we have one foot solidly trapped in the past,” says a former union organizer who spent years as a political prisoner under Pinochet. “Pinochet is dead, but Pinochetism is very much alive. We are constantly bumping into it.”

While a clear majority of Chileans look upon the Pinochet era as the darkest chapter in their history, a significant minority — as large as 40% — continues to admire Pinochet and believe that he made Chile great again, or at least tried to. This view is often held most ardently by the wealthiest Chileans who benefited the most from the annihilation of leftist parties and organizations, the suppression of unions and widespread privatization.

Many such people could be found on a recent warm Saturday morning standing in line to enter Chile’s tallest building, the 62-story Gran Torre, five stories of which are lined with the 300 designer shops and pricey eateries that populate the gleaming Costanera Center, Latin America’s biggest mall. While something like half the national population is mestizo, nearly all of the shoppers at the Gran Torre are of strict European lineage, with skin color and hair several shades lighter than most Chileans. What darker Chileans are seen at the mall carry no shopping bags, as they cannot afford the shop’s goods, such as designer tennis shoes costing $200 — the average monthly social security pension. They might as well be visiting a foreign country.

Dig deeper Mar 8, 2023How the Big Awakening Became a Hangover

Chile's new constitution failed. Now its leftist president is trying to reignite hopes for change. Chile's President Gabriel Boric is seen through a light fixture as he listens to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz during a ceremony at the La Moneda presidential palace in Santiago, Chile, Sunday, Jan. 29, 2023. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Chile's President Gabriel Boric is seen through a light fixture as he listens to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz during a ceremony at the La Moneda presidential palace in Santiago, Chile, Sunday, Jan. 29, 2023. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

March 11 marks the first anniversary of the inauguration of Gabriel Boric, the bearded and tattooed 37-year-old millennial president of Chile. The leader of the first leftist government since the overthrow of Salvador Allende in 1973, Boric is a former university protest leader who rose to power outside the traditional party system after a “social explosion” in 2019 that violently redrew Chile’s political map. His election seemed to augur a period of deep political reform, a “second peaceful revolution” that would resume the one initiated by Allende, for whom I served as a translator until the coup forced me to flee the country.

Upon my return to Santiago in January, it didn’t take long to understand that Chile had taken a different course, and that the reform process had entered a downcycle. “Right now, there’s a disenchantment with politics and social mobilization – a very bad hangover,” Hassan Akram, a professor and former adviser to Boric’s campaign, told me inside the studio where he broadcasts a radio and YouTube show called “The Voice of Those Left Behind.” Located a few blocks from the national palace, the studio buzzed with 30-something members of Akram’s alternative media collective, busy with preparations for the expected arrival of the day’s guest, the feminist social scientist and first lady of Chile, Irina Karamanos, 33.

“If social mobilization is cyclical, this is the low point,” says Akram. “The peak was in 2019.”

Dig deeper Dig Discussion