The original neoconservatives were a clique of mostly Jewish intellectuals who reacted, to one degree or another, against the Great Society and the radicalism of the New Left. The epithet neoconservative was coined by democratic socialist Michael Harrington to accuse the dissidents — who styled themselves as moderate, empirically oriented New Dealers — of joining the right.

This accusation soon became prophecy. Irving Kristol embraced the term, quipping that a neoconservative was “a liberal who had been mugged by reality.” Most neoconservatives did join the conservative movement, melding into its network of think tanks, foundations, and magazines so seamlessly it eventually became difficult to determine what the “neo” even meant. By the late 1990s, their sole remaining distinction from the rest of the movement was a fanatical belief in the transformative power of the American military. After the Iraq War, their influence faded. (In a final, redemptive act, many second-generation neocons left the Republican party over Donald Trump.)

One can see the same trajectory, or perhaps the early stages of it, in the career of Bari Weiss. Weiss resigned from her editing position on the New York Times op-ed page in 2020 when the paper was convulsed by a radical upheaval that claimed the careers of several of her colleagues. Like the original neoconservatives, she is a Jewish intellectual singed by radicalism and protective of Israel. Also like the original neocons, she does not describe herself as one. (Weiss identifies as a “classical liberal,” a creed she believes is being left behind.)

Unlike the neoconservatives, however, Weiss has not joined the conservative network. Instead, she has created her own institution: The Free Press, an online newspaper that has published for just over a year and already has 540,000 email subscribers, of whom 77,000 pay for its content.

Weiss’s site is interesting as well as frequently infuriating, though not in proportion to the rage Weiss herself frequently inspires. (Most recently, six TED fellows resigned to protest the insult of Weiss and activist hedge funder Bill Ackman merely being invited to address a TED conference.) The Free Press is both a journalistic project and a political one, prodding moderates and liberals to abandon the Democratic Party over a similar suite of issues (radical campus activism and elite acquiescence) that sent the neocons hurtling rightward in the late ’60s and ’70s.

The journalistic premise of The Free Press is that, because the mainstream media has abandoned traditional norms of objectivity on subjects related to identity issues, a coverage gap is available to be filled. Also, progressive activists employ pressure, both externally (through social media) and internally (through the tactics of left-wing staff) to force coverage to comply with the progressive line.

This critique is not without truth. It was most clear in 2020 when a wave of social-justice activism raised the evidentiary bar to report clearly on events like a spike in the murder rate, the plausibility of a lab leak as an origin of COVID-19, or other narratives that progressive activists considered politically inconvenient. At the same time, that spirit of activism lowered the bar for reporting claims favored by progressive activism, allowing truly strange reporting to appear. Media organs have corrected some of these lurches to the left but not entirely.

That bias has allowed The Free Press to break a number of stories that were either missed, ignored, or misreported by the mainstream media. It debunked widely circulated claims that a Canadian Catholic school for Indigenous children contained mass graves, a conclusion the mainstream media eventually confirmed. It broke stories about a Brooklyn public school using a Qatari-funded map of the Middle East that eliminated Israel, political drama at the Audubon Society over demands to change its name to de-honor its slave-owning founder, and Harvard biologist Carole Hooven’s account of her cancellation for stating that sex (but not gender) is binary.

The most explosive Free Press story, and the one that exemplifies its necessary role, was an account by Jamie Reed, a whistleblower at a children’s hospital in St. Louis. Reed alleged that the hospital’s Transgender Center at which she worked was giving children sex-change hormones with little diagnosis and often ignoring their serious mental-health problems. Reed’s account came at a precarious moment when doctors were trying to sort out the correct protocols for treating gender dysphoria and left-wing activists were applying intense pressure on the mainstream media to ignore or downplay the concerns of experts in the field. Reed’s claims tracked the fears of many of those providers, adding extensive, disturbing details.

The response by transgender-rights activists and their allies was volcanic. Influential progressive critics dismissed Reed’s claims as “wild and implausible” and “a pile of garbage.” They described her as a “front-desk staffer” and “someone performing a functional role at a clinic treating transgender youth” who had “started absorbing right-wing memes.” In short order, they settled on the shorthand “helicopter lady” and described her as lying, insane, or both. The term helicopter lady refers to one case cited by Reed in which a mentally ill child who told the clinic they identified as an “attack helicopter,” which is an internet meme, was treated for gender dysphoria without the exploration of any confounding mental-health conditions. Articles began appearing with headlines like “Journalist Thinks Trans Kids Are Getting Hormones to Turn Into Helicopters.”

A deep investigation by the New York Times could not confirm (or refute) all of Reed’s charges, but it was able to corroborate many of her most important claims. Far from being some deranged secretary, Reed was deeply involved in the clinic’s work, and her concerns were shared by medical practitioners there.

The Reed story is a perfect encapsulation of how progressive activists managed to override truth-seeking norms for the sake of what they believed to be social justice and why The Free Press, or something like it, needs to exist. Mainstream media institutions face, to varying degrees, intense pressure to make their reporting conform to progressive narratives. Reporters in traditional political journalism — the ones covering Congress, state legislatures, and political campaigns — still resist that pressure and follow norms of objectivity. But coverage of culture and social issues, which has expanded dramatically as dedicated beats on race, gender, climate, etc., increasingly tend to echo the messages of progressive activists with little scrutiny.

Holding progressive activists accountable like other political actors, rather than treating them as authorities, is an essential journalistic practice that mainstream media organs have ignored with growing frequency. The echo chamber of misinformation that surrounded the Reed story is a symptom of that deeper sickness.

The traditional alternative — conservative media — is hardly an antidote to the problem. The right-wing press barely bothers to pretend to uphold traditional journalistic norms at all, functioning openly as an organ of the conservative movement. The niche discovered by The Free Press is deep skepticism about progressive social values from people like Weiss who come out of journalism, not the conservative movement.

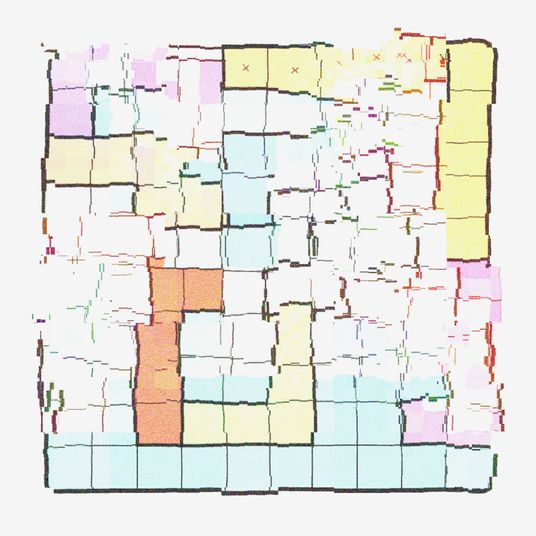

The trouble with The Free Press surfaces when you stop judging it as a corrective to blind spots in the progressive worldview and begin judging it as a worldview in and of itself. While it bills itself as merely a throwback to the abandoned creed of objective reporting —“built on the ideals that were once the bedrock of American journalism” — The Free Press does have a worldview. It reflects the frustrations of college-educated moderates, disproportionately Jewish, in big cities and other enclaves of progressive America. But those frustrations, while often grounded in reality, ignore the vast swaths of reality outside blue America.

Weiss does not require every story she runs to conform to her beliefs; she criticized Elon Musk, an erstwhile ally, and published a critique of Israel by Andrew Sullivan. But both the site’s choice of topics for news coverage and the tenor of its opinion journalism naturally revolve around her own worldview.

The Free Press has flooded the zone with laudatory coverage of former liberals alienated by left-wing identity politics in their progressive networks and communities. Peter Savodnik profiled “The Hollywood Power Brokers Mugged by Reality.” (Note the old neocon slogan reappearing.) Suzy Weiss and Francesca Block wrote about how “the left’s reaction to the massacre in Israel has many progressive Jews in the West rethinking their past activism, political affiliations, and friendships.” Bari Weiss and Oliver Wiseman reported on the same phenomenon (“Liberal friends were suddenly talking about buying guns. Progressive friends were texting about topics like border security and immigration. In a whisper, one even admitted to watching Fox News.”) The all-but-explicit message of these stories is that other moderate liberals put off by the radical left should follow Weiss’s own journey.

Weiss has defined her beliefs in simple, unobjectionable terms. “I hate bullies, period,” she told one interviewer. “Sometimes bullies are professors, sometimes bullies are students.”

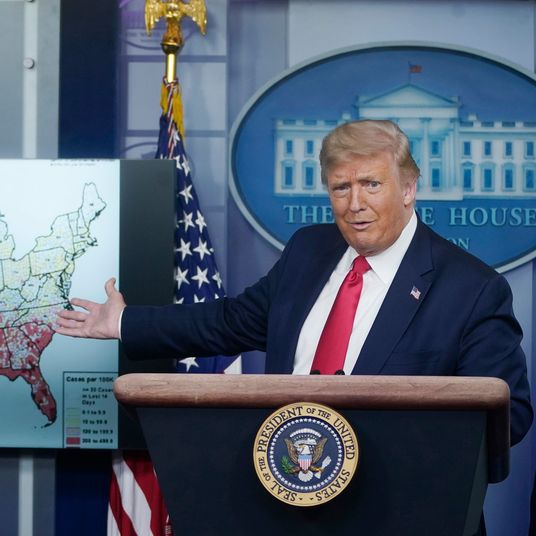

And sometimes, bullies may be neither a professor nor a student but, say, a billionaire presidential candidate. But Trump, even though he embodies the traits of a bully so completely that people suspect he was the model for the scenery-chewing heavy in Back to the Future Part II, does not seem to activate Weiss’s anti-bullying instinct.

Weiss’s 2020 resignation letter from the Times mocked the paper’s “Opinion” page for publishing too many anti-Trump columns. “Why edit something challenging to our readers, or write something bold only to go through the numbing process of making it ideologically kosher, when we can assure ourselves of job security (and clicks) by publishing our 4000th op-ed arguing that Donald Trump is a unique danger to the country and the world?” she asked rhetorically.

There might have been a point in believing Trump-bashing had gotten too easy. But The Free Press has increasingly adopted a defensive posture toward the former president, in which Trump has come to represent the antithesis of blue America’s insularity. “Whether they realize it or not, this is why Democrats truly hate Trump. Without him, the left would soon have had a pretty permanent monopoly on power,” argues one typical recent column.

Another column laments that “rather than trying to understand Trump’s voting base, many in the media have villainized them as fascists.” The posture of openness and curiosity is highly selective. The Free Press makes little effort to sympathetically understand the perspective of Americans who despise Israel and is more than happy to tar them as fanatics and bigots. It is also perfectly willing to use fascism comparisons for modern American phenomena when the target is, say, Harvard University.

The Trump depicted in The Free Press is less an independent actor than the passive object of left-wing zeal. One especially telling recent column casts Trump as the “funhouse mirror” of the left, an “epiphenomenon,” a “club in the hands of an alienated public,” a man whose behavior should not be seen as “personal attributes” — that is to say, a political actor whose choices do not reflect badly on his supporters, or even himself, but on his opponents:

Trump appears to act as a sort of funhouse mirror on which the progressive elites who run most institutions, including the federal government, see themselves reflected in the most monstrous and frightening light … Trump is once again an epiphenomenon: a club in the hands of an alienated public, with which to bash the elites and their unresponsive institutions … We should never think of Trump’s vulgarity and weirdness as personal attributes. They are political signals. It’s his way of saying, “I am not them,” of standing apart — while making rude noises — from the petrified dignity of elite politicians …

The melee that surrounds him on all sides, we should remember, is an asymmetrical fight: Those seeking Trump’s annihilation own most of the levers of power. Trump now roars down the express lane to the Republican nomination. To win in November, however, he will need a strategic brilliance he has never before demonstrated, or else a whole lot of luck. More likely, “our democracy” will intervene and he will be broken on the wheel of elite hatred before Election Day.

While The Free Press does not have a formal editorial line, this arresting image of Trump being broken, Christ-like, “on the wheel of elite hatred” is the culmination of a belief system that cannot imagine any system of power that is not left-wing.

And it is certainly true that if you live inside Hollywood or the New York Times or an Ivy League university, Trump and his supporters are mere hate objects. Weiss has built a publication speaking on behalf of a faction that cannot see the parts of the country where the right commands very real power.

In a speech to the conservative Federalist Society in November, Weiss told the assembled crowd that while they had differences over subjects like abortion, “I know who my allies are,” and urged the audience to “accept that you are the last line of defense and fight, fight, fight.” It is not that Weiss has abandoned all of her liberal or moderate beliefs; it is just that she has decided they don’t matter very much and that her allies are on the political right.

To build a worldview entirely in reaction to the excesses of one side is eventually to cooperate in the excesses of the other. The boomer neocons who began with revulsion at campus radicals wound up linking arms with the radical right. At some point, Weiss will stop denying that she is engaged in a political project and recognize that she has become a conservative, newly.