Don’t expect US-China relations to significantly improve in 2023

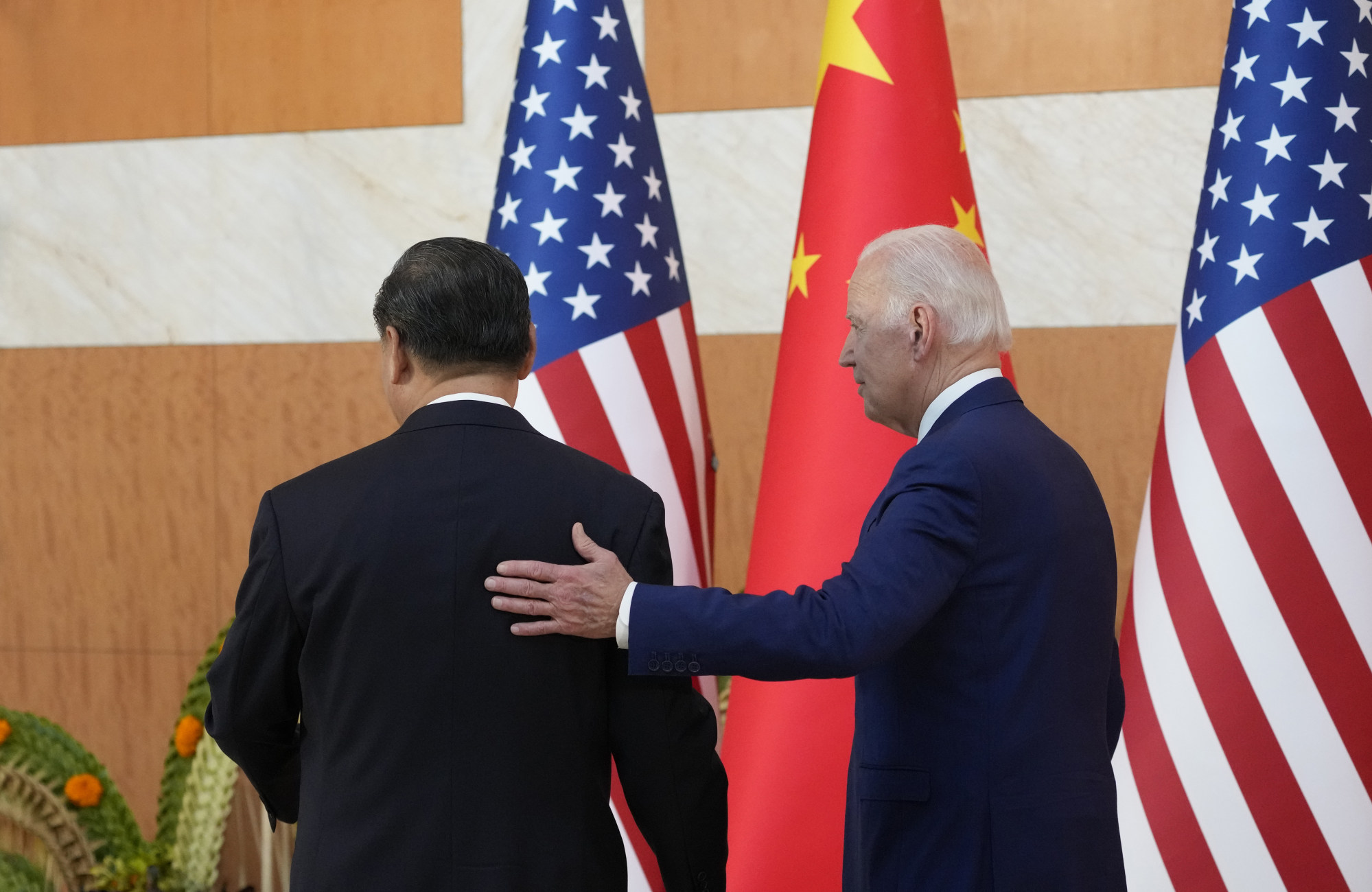

- Xi and Biden may have managed to avoid a US-China conflict in 2022, but their meeting won’t change the long-term course of bilateral relations

- As long as Washington sees China as a threat to be contained, its provocations are unlikely to cease

Since the beginning of 2022, Washington had relentlessly waged ferocious attacks on China.

To justify its unprovoked actions against China and win over its allies, Washington has been at pains to portray China as a bad actor that undermines rule- based international order.

Initially, China’s response was restrained and principled. Instead of tit-for-tat retaliations, it opted to concentrate on developing a strong economy and protecting the health of its citizens against Covid-19. In keeping with its commitment to maintain global supply chains, it has blacklisted fewer than a dozen American companies and individuals, and has not placed any ban on its exports to the US.

This flurry of high-level interaction has raised hopes of better times ahead. People-to-people exchange may be allowed to proceed, and tariffs on Chinese imports are likely to be lifted in part. But a fundamental improvement in bilateral relations remains a remote possibility.

McCarthy visit? How Beijing can nip the next Taiwan crisis in the bud

Moreover, the approach smacks of trickery. It is designed, commenters say, to undercut the established principles that Washington finds to its disliking, and to constrict China while giving Washington as free a hand as possible.

By all indications, Washington may try to place financial responsibility on China far beyond its fair share and ability to deliver, so as to slow the pace of its development.

In addition, the Biden administration would seek to reassume its global leadership by bringing China into its fold. Clearly, “cooperation” in the lexicon of Washington has strong connotations of geostrategic calculus.

To crown it all, the fiscal 2023 National Defence Authorisation Act passed on December 23 authorises US$10 billion in military aid for Taiwan.

In the new year, as Washington is expected to double down on decoupling with China, and its technological blockade against China looks to intensify. Many anticipate the White House’s export ban to be extended to China’s other hi-tech sectors.

So too will Washington continue to clamour about human rights as an opening to interfere in China’s internal affairs. It will continue to stir trouble in Asia through its so-called freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea.

With 2022 behind us, bilateral ties this year look likely to be marked more by tensions than by rapprochement. Indeed, as long as “outcompeting China” continues to plague Washington, stable and constructive relations will remain elusive as ever.

Zhou Xiaoming is a senior fellow at the Center for China and Globalization in Beijing and a former deputy representative of China’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations Office in Geneva