The short version: Borderline personality is a condition where people’s emotions, assessments, and self-image swing around wildly. Its most destructive feature is sudden extremes of negative emotions with high associated suicide risk. The best treatment for borderline personality is dialectical behavioral therapy, which you should get at a reputable Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Center that combines individual and group treatment. You may also want to consider taking medication as prescribed by your doctor and supplementing with fish oil. Borderline personality usually becomes less severe as a patient grows older, and the long-term prognosis is potentially good.

The long version:

1. What is borderline personality?

Everyone has their own conception of borderline personality. I think of it as being metaphorically very light, like a leaf in the wind.

If you’re very heavy, small gusts of wind barely move you at all. When something good happens, you are only a little happy. When something bad happens, you’re only slightly sad. But if you’re a leaf, then the slightest breeze can carry you basically anywhere. You have no weight, no inertia. The smallest setback can push you all the way to intolerable misery. The smallest victory can push you into ecstatic joy.

The most noticeable feature of borderline personality is extremes of emotion. Some people argue that borderlines are unusually bad at handling emotions. I don’t think this is true. If you ask them their techniques for dealing with emotion, they usually know better ones than most people. They just have stronger emotions. Just as it’s easy to budget when you’re rich, it’s easy to practice good coping strategies when nothing bothers you too much. But if your emotions are orders of magnitude stronger than most other people’s, even great coping strategies won’t always be enough.

Likewise, I don’t think borderlines have some special extra tendency toward suicidality and self-harm. I think it’s natural to start thinking about those things when confronted with emotions beyond your ability to control. A lot of people will, at the worst moment of their lives, when everything is crashing down around them, consider killing themselves. But most people get that level of misery once in a lifetime, whereas borderlines might get it once a month.

But it isn’t just an emotional lightness. Certain thought processes in borderlines are inherently light, in a way that prevents them from converging on an outcome and leaves them blowing back and forth. The most famous symptom of borderline is “splitting”, where a patient switches between “idealization” and “devaluation” – in normal terms, they love you until they hate you. Since most psychiatric literature is written by doctors, the typical example is a borderline praising their psychiatrist as the best doctor ever, saying they’re kinder and smarter and better than all the other doctors they’ve ever had and now they’re practically cured. Then the first thing goes wrong – maybe you’re running late and you make them wait a while – and you’re an evil abusive quack who’s trying to ruin their life. This is cognitive lightness – their opinion is getting blown around on the wind. An ordinary person might have some heavy, stable base opinion of their doctor, which gets only slightly better when their doctor does something good, and only slightly worse when they do something bad. A borderline’s opinion doesn’t have that weight, that stability. The slightest negative event will send it flying all the way down to the bottom of the chart. If you imagine a specific event as exerting a certain amount of force, as literally pushing an opinion in some direction, it will push a lead weight only a tiny distance, and a beach ball very far. The borderline is the beach ball.

This is bad enough when it’s your opinion of your doctor. It’s worse when it’s your opinion of yourself. The DSM’s fourth criterion for borderline personality is a “persistently unstable self-image”. The classic example is the borderline college student who starts by majoring in Art, then switches to Chemistry, then to Business, then to Classical History, and so on. An ordinary person knows what they like, and a minor update – like seeing a movie that makes chemistry look fun – only pushes them a little. But if your self-image is very light, that same movie might make you switch your entire self-image and life plan.

Because borderlines can’t get a clear self-image in the normal course of things, they often err on the side of becoming extremely distinctive just so they feel like anything at all. A borderline teen might become really Goth – dressing in all black, talking about vampires all the time, et cetera – because at least then they have one adjective that definitely describes them (“Goth”) instead of floating around on the winds of uncertainty. Many borderlines radically alter their appearance – hair dyed unnatural colors, unusual hairstyles like mohawks, tattoos or very visible piercings. For the same reason, borderlines enjoy anything where they have to play a clearly defined role – whether that’s theater productions or BDSM.

— 1.1. Can you be a little less metaphorical and a little more scientific?

In a Bayesian model of cognition, borderline is a tendency to underweight the prior relative to the posterior, or maybe difficulty forming priors at all. So for example, if you have a certain happiness set point, your current happiness should be some function of your prior (that set point) and your current evidence (whatever has recently happened to shift that set point). Borderlines underweight the set point and overweight the current evidence. Normally your emotional judgments would come from an average of your whole history of experiences, with your present experiences weighted a little higher. Borderlines’ judgments will be based almost entirely on present experiences, with everything else that’s ever happened to them barely registering.

In general, children make larger updates and are more “cognitively light”, and older people make smaller updates and are more “cognitively weighty” (compare machine learning, where programmers start an AI with a large update size, then lower it gradually as training progresses). That means people with borderline personality have a more childlike emotional processing style, which is something psychologists have been remarking on for the better part of a century.

The idea of update size and evidence-weighting gets more complicated when we start thinking about things other than a one-dimensional line from “happy” to “sad”. What does it mean to not be able to average your various judgments of your doctor? Your mother? I think this is the same thing psychoanalysts mean when they talk about “unintegrated material”. You have many different pictures of your mother, but they never cohere into a single person. Instead of getting a unified model of your mother as (eg) a decent human being with some flaws, you have a lot of snapshots of her that never quite connect.

If you can’t integrate various perspectives on yourself, you end up with various interesting pathologies, the most famous of which is Dissociative Identity Disorder, aka multiple personalities. About 70% of people with DID are diagnosed borderlines; the numbers are so high that some researchers are not even convinced that these are two different conditions; maybe DID is just one manifestation of borderline, or especially severe borderline.

— 1.2. How do doctors diagnose borderline?

I don’t usually quote DSM criteria because they’re usually just annoying ways of restating the obvious. The DSM criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, for example, are just a bunch of different ways of saying “is anxious”.

Borderline is more interesting. The criteria mostly don’t have any obvious relationship to each other. When I read them off to borderline patients, they usually look at me like I’m a psychic – how am I able to predict so many different facets of their personality? But I think they all make sense in the context of lightness and the extreme emotional and cognitive shifts it causes.

For the record, the criteria are:

1. Chronic feelings of emptiness

2. Emotional instability in reaction to day-to-day events (e.g., intense episodic sadness, irritability, or anxiety usually lasting a few hours and only rarely more than a few days)

3. Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment

4. Identity disturbance with markedly or persistently unstable self-image or sense of self

5. Impulsive behavior in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging (e.g., spending, sex, substance abuse, reckless driving, binge eating)

6. Inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger (e.g., frequent displays of temper, constant anger, recurrent physical fights)

7. Pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by extremes between idealization and devaluation (also known as “splitting”)

8. Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats, or self-harming behavior

9. Transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms.

But outside the official criteria, there are some traits that are common in borderline personality disorder.

Borderline personality is diagnosed about three times more often in women than men. Nobody is exactly sure why. Certainly some symptoms (like being flighty and emotional) fit classic female stereotypes. It might just be a self-perpetuating problem; doctors remember that all the patients their medical school professor ever pointed out as borderline were women, so their model of the disorder is female-slanted.

But antisocial personality is diagnosed about three times more often in men than women. And in genetic studies, the genes that cause antisocial personality and borderline personality are pretty similar – similar enough that it’s worth wondering if they’re the same disorder. Either stereotypes are causing doctors to diagnose male patients with a certain condition as “antisocial” and female patients with the same condition as “borderline”, or some real difference in male vs. female biology is causing the same genes to manifest themselves differently depending on gender.

In either case, it’s worth remembering both that borderline as we currently understand it is female-dominated, but also that there are lots of male borderlines who tend to get missed or misdiagnosed because nobody remembers it’s a possibility.

Some doctors note that childlike traits are common in borderline personality. One famous example is the tendency for borderline patients to bring stuffed animals to the psychiatric hospital; see eg Adult Attachment To Transitional Objects And Borderline Personality Disorder, where “transitional object” is a fancy psychiatric term for a stuffed animal or doll. My interpretation of this is that any prior-less / cognitively “light” mental state will resemble childhood, since the key cognitive feature of childhood is low levels of past experience to average present experience with.

Dr. Marco del Giudice theorizes that borderline personality is some kind of collection of traits that evolved in order to make people more interesting and attractive, maybe making their posture/expressions/reactions more youthful-seeming by altering the entire nervous system into a more childlike state. I am kind of skeptical of this because I think level of weight assigned to cognitive priors is a pretty basic computational parameter and it makes sense that it would be too high in some people and too low in others. But he is an associate professor of psychology and I’m not, so maybe take his word over mine.

But I bring this up because a lot of people with psychiatric conditions wonder if they’re flawed, or they’re worse than other people. While some psychiatric conditions are clearly really bad, I think most of them have some kind of evolutionary justification or counterbalancing advantage. People with borderline personality seem to be more creative, attractive, charismatic, likeable, and able to excite people (romantically and otherwise). They may even be more romantically desirable on average: see for example Borderline personality traits in attractive women and wealthy low attractive men are relatively favoured by the opposite sex (or read this article about the study).

BorderlineArts.com, a site by and for people with borderline personality, lists famous people who probably had borderline personality, including Marilyn Monroe, Jim Morrison, Angelina Jolie, and maybe Princess Diana; other lists include Vincent van Gogh. But it’s not just artists and entertainers and princesses – psychiatry is indebted to Marsha Linehan, the psychologist who invented dialectical-behavioral therapy and eventually revealed she was borderline herself.

(for speculation on another famous case, see Bui et al in Psychiatry Research 2011 Jan 30;185(1-2):299, Is Anakin Skywalker Suffering From Borderline Personality Disorder?)

And to give a completely different side of things, the top post on the borderline personality subreddit is this letter by a patient describing what borderline personality is like from the inside.

— 1.3 What’s the difference between borderline and bipolar?

About $100/hour.

See, some insurances would cover “Axis I disorders” but not “Axis II disorders” (don’t ask what this means, it’s a totally meaningless distinction). Borderline was officially an Axis II disorder, so insurances would not pay doctors to treat it. So with the best of intentions (ie ensuring their patients could actually get covered for treatment) doctors would kind of deliberately misdiagnose borderline personality as bipolar disorder. But they wouldn’t always tell the patient they were doing this, and they certainly wouldn’t write down on the chart they shared with other doctors that they were doing this. So a whole generation of borderline people ended up thinking they were bipolar, and sometimes even got incorrectly treated for bipolar. This was extremely unfair to them and I think stands as a strong indictment of the whole system.

Somebody with bipolar disorder alternates between periods of elevated mood (“mania”) and depressed mood (“depression”). This superficially resembles borderlines, who get blown around between hyper-positive and hyper-negative states. But borderlines’ moods tend to last a few hours, maybe a day or two, whereas bipolar depressions tend to last weeks to months and even manias are usually at least a few days to weeks long. Also, borderlines’ moods are almost always caused by something good or bad happening (even if the cause seems trivial to non-borderlines), whereas bipolar episodes are usually caused by circadian rhythm disruptions, generic stress, or nothing at all.

Manic bipolar people will usually sleep very little, have extreme spells of impulsivity (ie buy a sports car they can’t afford on a whim), be absurdly social or talkative, and sometimes lose touch with reality in a “positive” direction (eg they think they’re God or that they can invent cold fusion). Borderline people who have been blown into a hyper-positive mood by some good event will just be very happy in a normal (though intense) way.

Bipolar people may have rare manic periods when they’re angry, impulsive, et cetera. Borderline people will have a kind of consistent personality trait of being angry or impulsive in certain situations or as a response to certain problems. Bipolar people might get suicidal when they’re in the depths of a depressive episode. Borderline people will have a kind of consistent personality trait of being suicidal when things get bad enough.

That having been said, these are just some rules of thumb, and bipolar mixed states can sometimes look a lot like borderline personality. Also, some bipolar people can also have borderline personality at the same time, which is confusing. If you’re not sure if you’re borderline or bipolar, consider asking your psychiatrist, especially if you trust their judgment. Usually if asked outright about this a psychiatrist will tell you the truth.

— 1.4. What’s the difference between borderline and PTSD?

Many people have noticed that borderline patients tend to have a history of childhood trauma. Different people interpret this connection in various ways.

One group is skeptical. They note that susceptibility to borderline personality is at least half genetic. That doesn’t leave too much room for trauma to be a major cause. Also, it means borderline patients will probably have had borderline parents, which might mean their childhoods were unusually stormy and they will have a lot of childhood trauma to remember and (falsely) attribute their borderline personalities to. Also, because borderlines are have such intense emotions, they may be more likely to feel traumatized by any given level of childhood problems than someone else might be.

Another group takes this at face value. They agree that genetics are part of it, but they also think that childhood trauma disrupts the functioning of the HPA axis (= hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, the body system that produces adrenaline in response to stress) in a way that causes borderline personality later on.

And all of these is further confused by the debate around cPTSD (“complex post-traumatic stress disorder”). This is a still-not-officially-accepted variant of PTSD that you get when your trauma isn’t a single incident (like being ambushed during a war) but a long series of incidents you can’t escape from (like a child being abused by their parents). While everyone agrees the latter class of incidents can be traumatizing, cPTSD advocates argue that they can produce different symptoms from other traumas. In fact, they say it produces symptoms a lot like borderline personality; emotional dysregulation, disturbed self-image, dissociation, etc. How this relates to borderline personality is still unclear. Some people would argue they’re two different ways of looking at the same problem, or perhaps two slightly different manifestations. Others would argue that, because cPTSD is so little-known, cPTSD sufferers are constantly misdiagnosed as borderline, and that’s why so many apparent borderlines report childhood trauma.

I don’t think the science is settled on any of this. But if you’re borderline and you have a history of pretty awful childhood trauma, you’re definitely not alone.

2. How do you treat borderline personality?

Medications can help control the symptoms of borderline, but by far the most effective and definitive treatment is therapy. The best-supported therapy for borderline personality is dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT). The psychologist who developed DBT, Marsha Linehan, was borderline herself and spent years trying to figure out what worked for her and turning it into testable therapy techniques.

Real DBT involves a combination of individual and group therapy. It’s usually done at “DBT centers”, since the average psychiatrist or therapist won’t have enough time/experience/borderline patients to run their own therapy group. In my own state of California:

– The Bay Area has the San Francisco DBT Center, DBT Center of Marin, DBT Center of Silicon Valley, Pacific DBT Collaborative and Oakland DBT And Mindfulness Center.

– You can find a list of DBT centers in the LA Metro area here.

– San Diego has DBT Center of San Diego

If you’re somewhere else, Google “DBT center [my area]”. Most places will be called something like “The DBT Center Of [my area]” and will mention being certified, having certified therapists, or having a direct lineage from Marsha Linehan in some way.

These centers usually only exist in big cities, are expensive, may not take insurance, and ask you to make major time commitments. I recommend them anyway. They are the standard of care for borderline personality, borderline is a serious condition, and this isn’t the time to cut corners.

If you absolutely cannot find or afford a DBT center near you, there are various types of “DBT lite” available. Some ordinary therapists may have “DBT-informed” modalities, possibly including ordinary therapists covered by your insurance. Find these people by going to PsychologyToday, type your area into the Find A Therapist Tool, and set the “Type Of Therapy” filter to “DBT” (you might also want to filter for your insurance and other things important to you). This is less good than a real DBT center but better than nothing.

There’s also the Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Skills Training Manual, which is an awkward combination between a therapist training manual and a self-help book. I don’t get the impression it’s intended to be used by ordinary patients not also undergoing face-to-face therapy, but a motivated person could probably make it work. And I’ve heard some good things about The Mindfulness Solution For Intense Emotions, but also a warning that it gets kind of preachy about Buddhism at times.

— 2.1. But what is dialectical-behavioral therapy?

I’m not trained in this style of therapy, so this will be a very poor summary, but classic DBT has four pillars:

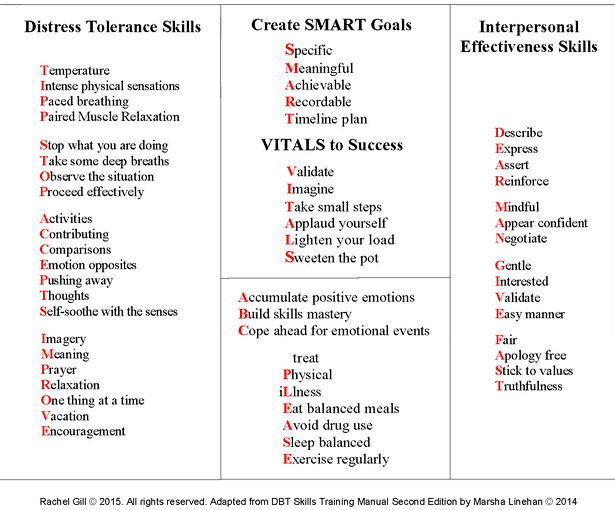

Group therapy skills training: These are grouped into mindfulness skills, social skills, emotional regulation skills, and distress tolerance skills. Mindfulness is a meditation-inspired practice of learning to be open and curious in the present moment instead of trapped in thought loops. Social skills involve setting and respecting boundaries. Emotional regulation skills involve how to cope with extreme emotions by doing things like noticing emotions, noticing the way emotions suggest actions, and figuring out how to respect and validate your emotions without taking destructive actions. Distress tolerance is things like taking deep breaths or splashing your face with cold water when you’re upset instead of self-harming.

Individual therapy: Similar to individual therapy anywhere else. You talk about what went on during your week. Your therapist listens and helps you think about how things went and brainstorm ways to make them go better. A lot of this involves learning how to apply the skills you learned in group training to your personal situation.

Therapist team: You don’t really have to worry about this one, it just means your therapist has support from other therapists and is getting good advice on your case.

Phone coaching: A typical example of this is that when you’re suicidal, instead of doing something drastic you call your therapist, and they walk you through using some of your skills to cope with the situation.

One unofficial pillar of dialectical behavioral therapy is long lists of silly acronyms. I won’t go so far to say that courses without enough silly acronyms don’t count as real DBT, but you’re definitely missing out on the full experience:

My pet theory is that this is a way of helping you practice your distress tolerance skills.

— 2.2. Can medications help treat borderline personality?

No medications have been proven effective for borderline personality itself, but some have some evidence for sometimes helping with specific symptoms.

Timäus et al do a remarkably good job giving us a cross-section of what drugs are used most often for borderline personality. Top of the list is antidepressants, at 68% of patients, then antipsychotics at 46%, then naltrexone at 36% (you’ll notice these numbers add up to more than a hundred; most people in the sample were on more than one kind of drug).

Since borderline is a condition of extreme emotions, and SSRIs antidepressants help blunt emotions, you would think SSRIs would be an exceptionally good borderline treatment. There are few high-quality studies here, but the little we know finds them to be surprisingly mediocre. It seems harder in borderline to find the sweet spot where the patient is less emotionally disturbed but still feels normal. I’m not sure why this is, but these are less of a miracle cure than we would hope.

(source)

Antipsychotics are very good at dealing with the occasional paranoia and delusions that stressed borderlines sometimes come up with, and can also more generally decrease emotions and behaviors. I’m deliberately framing this in a kind of scary-sounding way, but this is sometimes what very self-destructive and out-of-control people need. The most commonly used antipsychotics for this condition are quetiapine (almost half of all antipsychotic prescriptions here) and aripiprazole.

Naltrexone is the odd one out. Some people argue that, in its role of preventing things from being rewarding, it prevents borderline behaviors like self-harm from feeling good and makes people do less of them – though I have several objections to this theory. Other people argue that, by blocking existing opioid receptors, it triggers the brain to make more opioid receptors over the long-term; since opioid receptors are involved in feeling comfortable and accepting of things, this makes borderlines less distraught during crises. And still other people say it can decrease dissociation. Some low-quality preliminary studies seem to back this up, though see also this RCT which failed to find much of an effect on dissociation. This treatment should still be considered experimental.

Otherwise, we throw so many different things at borderline personality disorder that it’s embarrassing. Lithium, valproate, mirtazapine – for the exact list, check this paper. When we throw drugs this haphazardly at a condition they were never designed for, I think we’re probably sedating the patient more than treating them. Sometimes patients want to be sedated and benefit from sedation, but let’s not pretend we’re doing anything more principled than that.

If we’re going to sedate people, should we just do it properly and give them benzodiazepines? These drugs, which specialize in calming people very quickly for a short period of time, seem like a natural match for a condition marked by short periods of extreme distress. Still, everyone recommends against this. The usual justifications are that borderlines are at higher risk of addiction and benzos are potentially addictive, and that benzos can sometimes paradoxically disinhibit people and make them even more reactive and dangerous. I’m not sure how much I buy these. Benzos are potentially addictive for everyone, but you screen patients carefully and try to watch what they’re doing with their meds. And benzos show paradoxical disinhibition in about 10% of people in general, but I’ve never seen any reason to believe this is more common in borderlines. I would rather a borderline patient have Ativan 1 mg PRN crisis max 1x/week, than take 400 mg of Seroquel every day. But I admit I’m in a minority here and am hanging a lot on “you can screen patients for addiction risk”.

DBT is almost certainly better than any of this.

— 2.3. Can supplements help with borderline personality?

Omega-3 fatty acids (ie fish oil), 700 mg EPA + 480 mg DHA daily.

3. Is there a lot of stigma around borderline personality?

Mental health providers will tell you yes, which makes sense because there’s a lot of stigma among mental health providers. While borderlines can be good friends, coworkers, et cetera, they can be difficult patients, so a lot of providers are afraid of them or avoid them. This has led to a lot of mental health providers thinking there’s lots of stigma full stop, plus not-especially-productive public awareness campaigns where providers try to lecture the public about how they should avoid stigmatizing borderlines in a way that (to my mind) is mostly projection.

My impression – confirmed by a few borderlines I talked to for this article – is that people who aren’t mental health providers have mostly never heard of borderline, or have some vague association that it means someone is a bit crazy but also wild and exciting.

— 3.1. Does having borderline personality make me a bad person?

The other place where you get a lot of negative information about borderlines is from people with bad past experiences, often ex-es or family members. Some of these people go around saying they are all emotional abusers, or all bad people. The Reddit support group for borderlines’ friends and family members, r/BPDLovedOnes, veers into this kind of discussion sometimes.

But I don’t think “bad person” is a productive way of thinking about things. As a metaphor: poor people are more likely to commit certain kinds of crime, like shoplifting and mugging. This isn’t because they’re worse people; it’s because they’re needier people, and when you’re really needy, sometimes you do things you’re not proud of in order to survive.

Since borderlines can experience much stronger emotions than other people, they’re more likely to do some of the bad behavior that comes with strong emotions, like yelling or getting in fights or being violent. This isn’t because they’re worse people, it’s because they’re fighting a harder battle and facing more temptation. Anyone can be friendly and calm and gracious when everything is going well. But when people feel threatened and overwhelmed, sometimes they snap. If you feel threatened and overwhelmed a few times in your life, then you might snap a few times; if you feel threatened and overwhelmed almost daily, you might snap almost daily. Borderlines tend to fall in the latter category.

I hate alcohol and I can’t drink it even if I try. I don’t think that makes me more “virtuous” than an alcoholic. It just means I was born with an unfair advantage. I have more respect for the naturally-alcoholic person who sweats and bleeds every day to stay sober (and maybe slips up once or twice) than I do for the person who never drinks alcohol because they have no interest in it. In the same way, I think borderlines deserve respect for managing temptations much harder than most people have to deal with, even if they slip up sometimes.

If you yell at people, manipulate people, threaten people, or use violence, you already know those things are bad. Knowing that you do them “because you’re borderline” doesn’t make you a worse person. It explains why those things are so hard for you to resist, and helps point you in the right direction for how to improve.

And if, like many borderlines, you don’t yell at/manipulate/threaten/hurt people despite having really strong urges to do so, I think that you deserve a lot of credit for successfully managing a burden beyond what most people have to bear.

Also, this is one of the reasons I stress the idea of psychiatric conditions as having tradeoffs so much. If you have borderline personality, yes, there are probably a lot of ways it makes you harder to be around. But people continue befriending, dating, and marrying borderlines anyway, and evolution keeps producing them; there must also be extra reasons why they’re especially good to be around. You might not be the right person for everybody, but the people who appreciate you will appreciate you a lot.

— 3.2. How can I support/deal with a loved one who has borderline personality?

The people interested in this tend to separate into two groups. One group wants to help a borderline friend or loved one, and wants information about how to support them. A second group is fed up with a borderline friend or loved one and want people to validate this or give them permission to leave.

If you’re in the first group, you might benefit from books like Loving Someone With Borderline Personality Disorder and online communities like r/BPDSOFFA (Borderline Personality Significant Others, Friends, Families, and Allies).

If you’re in the second group, you might benefit from books like Stop Walking On Eggshells and online communities like BPDLovedOnes. Although someone with borderline might not be a bad person, if you feel like they’re abusing you, then they’re a bad person for you. Don’t hesitate to set boundaries or, if needed, get them out of your life. Guides to breaking up with someone with borderline personality are a surprisingly popular genre.

4. What is the prognosis for borderline personality?

Pretty good. From Biskin, The Lifetime Course of Borderline Personality Disorder:

Both studies found that most patients with BPD improve with time. The CLPS provides evidence that, even when followed up 2 years after the initial assessment, about one-quarter of patients experience a remission of the diagnosis (defined here as meeting less than 2 symptoms for a period of 2 months or longer) during the prior 2 years. During a 10-year period of follow-up, 91% achieve at least a 2-month remission, with 85% achieving remission for 12 months or longer. The MSAD has found similar results extended out to 16 years using a slightly different definition of remission (no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for a period of 2 years or longer) and found that by 16 years, 99% of patients have at least a 2-year period of remission and 78% have a remission lasting 8 years. Both of these studies also demonstrated that BPD is slower to remit than other PDs and MDD. Finally, 1 study followed patients after 27 years and found that 92% of them no longer met criteria for BPD.

Most borderlines get significantly better within ten years; almost all of them do after thirty.

This fits with the idea of borderline symptoms as involving a child-like cognitive processing style. If average update size goes down with age (ie cognitive “weight” goes up with age), then we can think of borderlines as having a fixed disadvantage in emotional maturity. But eg a ten-year deficit in emotional maturity at age 16 makes you 6, whereas the same deficit at age 40 makes you 30 – and 30 year olds aren’t that much less emotionally mature than 40 year olds. I don’t know if this is actually the right way to think about this but it helps me make sense of the otherwise quite-surprising numbers on how many borderlines “grow out of” their symptoms.

I think borderlines have a pretty good chance of being able to enjoy middle age; the important part is making it there without too much damage. The same paper notes that somewhere between 5% and 10% of patients diagnosed with borderline commit suicide. These studies tend to be pretty strict with diagnosis, which means they might be looking at the most severe patients and these numbers might be a little high – but I think this offers an important warning. There’s a related issue where older borderlines might suffer consequences of past bad decisions – for example, career issues from having dropped out of education when they were younger, problems from having already alienated family and friends, or continuing to struggle with addictions they developed during earlier years. But if they can make it there intact, I think it’s fair to see there is light at the end of the tunnel.

5. Where can I find more information about borderline personality?

borderlinepersonalitydisorder.org has some good resources, including a free course/support group for families and a list of useful links.

The Borderline Personality Resource Center tries to help connect people to treatment near them.

The subreddit for people with borderline personality can be a good place to meet literally like-minded people who share your struggles – though remember that any group full of similar people will develop its own biases and pathologies worth being careful about.

Marsha Linehan’s autobiography Building A Life Worth Living might not be a “resource” per se, but it’s a pretty impressive and inspirational book that I think a lot of people with borderline would appreciate.