What W. E. B. Du Bois’s Forgotten Romance Novel Taught Me About Writing

Dark Princess showed how the genre can open our minds to fantastic possibilities.

After my father’s death, I didn’t write for two years. Even reading fiction no longer interested me. But when a friend mentioned W. E. B. Du Bois’s Dark Princess, a romance novel published in 1928, I was curious. The novel had been disparaged and overlooked by critics; maybe that’s why I was attracted to it. Did Du Bois, the renowned social scientist and activist—whose seminal book of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, remains one of the most influential works of African American literature—really write a romance? I had never been a reader of the genre, but death had recalibrated so much of my relationship to the world that it was hard for me to be definitive about anything, even my own tastes.

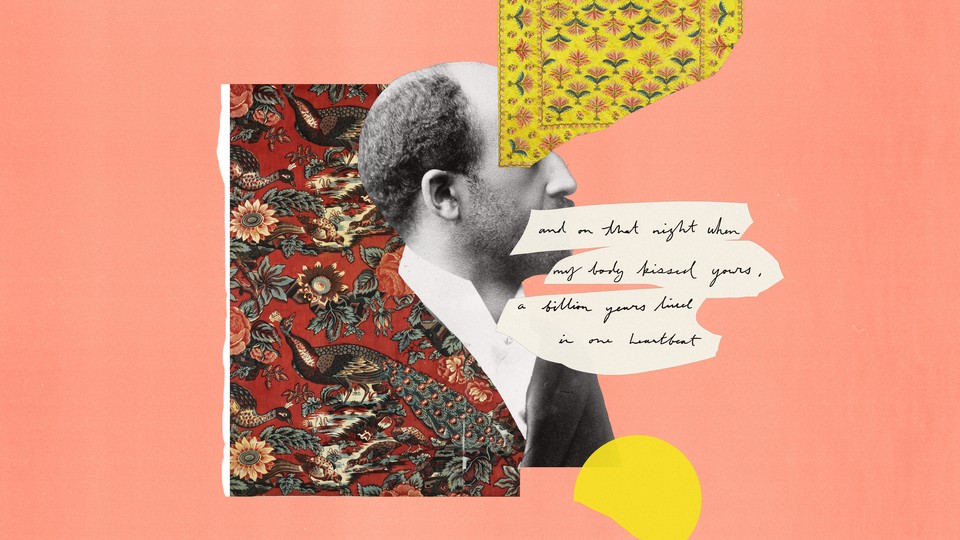

Dark Princess begins in New York City with Matthew Townes, an aspiring obstetrician who is prevented from continuing his medical studies because he is Black. After leaving school, he travels to Berlin, where he meets Kautilya—a purple-haired princess from India who invites him to join a secret coalition working to overthrow white imperialism and achieve self-sovereignty for the darker races. Ultimately, the book is a love story between Princess Kautilya and Matthew that spans years: Matthew ends up in prison in Chicago and later becomes involved in local politics, while Princess Kautilya works in factories and unions around the United States. When they finally reunite after years apart, Matthew says to Princess Kautilya, “And on that night when my body kissed yours, a billion years lived in one heartbeat. What more can I ask?”

It’s a surprisingly syrupy line for someone who wrote as seriously as Du Bois. But to me, it reveals a writer unafraid to embrace emotion. Near the beginning of the novel, Du Bois describes Matthew’s arrival in Berlin as an awakening—a reminder of everything he’d left behind in America, but also a hint at the possibility that lies ahead: “Oh, he was lonesome; lonesome and homesick with a dreadful homesickness. After all, in leaving white, he had also left black America—all that he loved and knew … What would he not give to clasp a dark hand now, to hear a soft Southern roll of speech, to kiss a brown cheek? … God—he was lonesome. So utterly, terribly lonesome. And then—he saw the Princess!” During the time after my father’s death, writing was difficult because my imagination had dimmed, and I was trying to feel nothing at all. But here was a book bursting with unapologetic desires, with optimism for what the world could be. I had believed that romance was a breezy daydream on a hot afternoon, but after reading Dark Princess, I realized that the genre could help us see beyond the limits of our reality, opening our minds to fantastic possibilities.

The novel contains an assortment of story lines that one might not expect to live together—the meeting of Princess Kautilya and Matthew in Berlin, the nitty-gritty details of the political milieu in 1920s Chicago, anti-imperial efforts in the global South, and racial-liberation struggles in America. The New York Times called it “flamboyant and unconvincing,” with “enough material in it for several novels.” The novel does feel uncontainable. But what excited me was its radical understanding of romance as a possible force for change. In her introduction to the 1995 edition, the critic Claudia Tate wrote that if “critics had judged the novel according to the values of an eroticized revolutionary art instead of the conventions of social realism, they probably would have celebrated Dark Princess as a visionary work.” Romance, with its tendency toward coincidences and melodrama, gave Du Bois’s characters the freedom to live and dream in a way that realist writing could not.

As a sociologist and historian, Du Bois, of course, mostly wrote in a mode that attempted to capture the world as it is. But he was also a uniquely brave and inventive writer. His books resist and refuse the bounds of genre; he realized that every form had the capacity to illuminate the human psyche. Writers sometimes hesitate to stray from their comfort zone for fear of how their work will be perceived. “Genre” fiction is also often dismissed in favor of realist literature. While accepting a lifetime-achievement award at the 2014 National Book Awards, Ursula K. Le Guin acknowledged her “fellow authors of fantasy and science fiction, writers of the imagination, who for 50 years have watched the beautiful rewards go to the so-called realist. Hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine some real grounds for hope.”

As Du Bois shows, genres such as science fiction and fantasy can be expansive tools of the imagination. In Dark Princess, the romance between Matthew and Princess Kautilya is also a symbol of the coalition’s vision of interracial solidarity. The birth of their son suggests a future utopia, one in which the boy will lead the people of “the Darker Worlds” as a sort of Messiah, showing them a way “out of their pain, slavery, and humiliation, a beacon to guide manhood to health and happiness and life and away from the morass of hate, poverty, crime, sickness, monopoly and the mass-murder called war.” Although certain aspects of Dark Princess, such as the orientalized representation of India and the one-dimensional nature of some of the female characters, didn’t resonate with me, I recognized the power in this act of imagining—even if, in the novel, the coalition ultimately doesn’t achieve its utopia. In the act of writing, of imagining, there is no failure.

Over the years, Dark Princess has lingered in my mind and encouraged me to be more experimental in my own writing. Before the pandemic, I had a fellowship at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, where I conducted research for a novel set in a future New York City in which AI governs many aspects of life. In that novel, Meet Us by the Roaring Sea, a young woman translates a manuscript that follows a group of female medical students who try to create a compassionate, communal way of life amid drought and violence. It is in part a love story that dips into many forms and genres, crossing borders, time periods, and gender norms. Writing in a genre like science fiction allowed me to see our world anew. What does it really mean to care about the suffering of others? How do we show that care? When the coronavirus pandemic hit, these questions felt even more urgent; it became clear how interconnected our lives really are. While writing, I found myself constantly slipping into the second person and the first-person plural, wanting to entangle the reader and evoke the collective.

In his 1940 book, Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept, Du Bois called Dark Princess his favorite work. He had kept his forgotten, unbeloved novel nearest to his heart, and I can understand why. The novel, which is dedicated to Titania, the fairy queen from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, ends with a question directed at her: “Which is really Truth—Fact or Fancy? the Dream of the Spirit or the Pain of the Bone?” With Dark Princess, Du Bois reaches for that dream and asks us to make it real.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.