With Ukraine claiming that Russia has committed as many as 25,000 war crimes, more than a dozen organizations are busy putting together indictments that they hope will eventually land soldiers, commanders and even Vladimir Putin in court.

On the surface, most of these are open-and-shut cases: unlawful killings including summary executions, forced detention, deportations and "disappearances" of civilians, torture and sexual assault. But in the bombing of Ukraine, establishing the basis for war crimes is far more difficult.

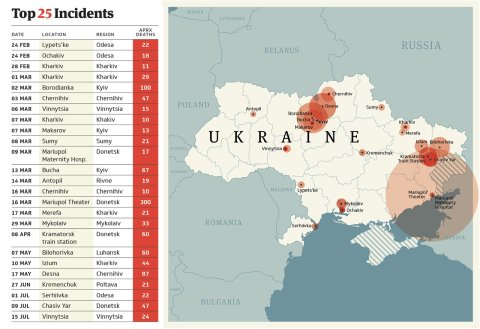

Newsweek examined the 25 top incidents of civilian deaths in the war. That two-month investigation has found that there is some truth to Moscow's assertion that it is not intentionally targeting civilians. The Russians have bombed civilian areas in cities where the ground fighting has been the most intense: in places like Mariupol, Kharkiv and Severodonetsk, to name just a few. Bombing with indiscriminate effect is a war crime. But in the 25 incidents Newsweek examined, the facts on the ground are much more muddled. Whether these incidents, totaling some 1,100 civilian deaths, are war crimes is a matter for the courts. Newsweek's conclusion is that none of the cases unambiguously qualifies.

The 25 Bombing Incidents with the Highest Casualty Count

Is Russia intentionally killing civilians? It seems outrageous to even pose the question, given the scope of bloodshed and the many strikes on hospitals, schools, homes and shopping centers that have been reported. But Newsweek has found that determining why such objects were bombed often reveals a more difficult narrative. In most incidents, the intended Russian targets were indeed military in nature. And there are many cases where civilians were killed because weapons—Russian and Ukrainian—just failed to work.

Ukrainian authorities tell Newsweek that they are currently investigating, as war crimes, about 5,000 cases of damage to civil objects, 2,000 illegal deaths and injuries of civilians, and 166 cases of torture. The Office of the Prosecutor General has identified some 600 Russian war crimes suspects, almost all of them soldiers who are accused of everything from rape and torture to outright murder.

To be strictly fair, though—and controversial as it may be to point out—Ukraine has also played a role in the civilian casualties, consistently placing its military forces inside urban areas or attacking Russian forces when they are doing the same, an almost inevitable consequence of battling invaders in a crowded city.

None of this is to blame Ukraine or excuse Russia's aggressive and unprovoked war, the behavior of its soldiers on the ground, or its style of missile and artillery warfare that in some ways has been inherently indiscriminate. Yet establishing Russian intention to actually kill civilians is difficult. Even as the United States and NATO redouble their efforts (and increase their budgets) to prepare for a grand war in Europe, politicians, the media and the public ignore the destructiveness of a ground war, conflating its many unavoidable effects with "war crimes." The mistaken belief that the civilian tragedy in Ukraine is solely the result of Russian design only makes our understanding of future wars more difficult.

What is a War Crime?

On June 27, a Russian missile slammed into the Amstor shopping center in the central industrial city of Kremenchuk, killing 21 civilians and injuring another 100. The response was electric. President Volodomyr Zelensky said Russia was on a "killing spree," labeling the attack "one of the most daring terrorist attacks in European history." French President Emmanuel Macron called it an "abomination." The Group of Seven leaders, then meeting in Germany, issued a joint statement: "Indiscriminate attacks on innocent civilians constitute a war crime," it said. "Russian President Putin and those responsible will be held to account."

International law imposes limits on the conduct of war, including what types of weapons can be used and how they can be used. The general rules, as contained in the Geneva Conventions and other treaties and agreements, revolve around the obligation to distinguish between military and civilian objects. Thus indiscriminate attacks are prohibited, and the warring parties must apply the principles of precaution and proportionality in undertaking attacks.

"Even where a military target exists, using disproportionate force while knowing that the strike will likely cause death or injury to civilians or damage to civilian structures is a war crime," says David Sheffer, the first United States Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues.

What is more, while minimizing civilian casualties and damage to civilian objects is a fundamental obligation, it is not absolute. If "military necessity" demands, attacks may be justified. A civilian object such as a supermarket (or even a hospital or a school) that is being used by the armed forces (in such a way that its destruction offers a "definite military advantage") can become a legitimate military target.

Weapons that are indiscriminate by their nature or those that cause "superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering" are also prohibited. Certain types of weapons (such as poison gas) are outright banned, while others have to be used in particular ways. Even Russia's own military manual relating to the law of armed conflict says that "all types of weapons of an indiscriminate character or that cause excessive injury or suffering" are prohibited. This principle is important, especially when Russia is using obsolete and unreliable missiles, such as the massive 1960's era Kh-22 missile that hit the supermarket in Kremenchuk.

Oceans of words have been spilled to determine the meaning of the many terms and phrases seeking to place limits on warfare. Violations of international law are not the same as war crimes, which are generally defined as "grave" breaches of the law. There are certain acts that constitute war crimes under all circumstances—torture, sexual violence and inhumane treatment, deliberately targeting civilians and intentionally striking certain types of objects (such as religious objects), among others. But the phrase also has a precise and technical definition, and the bar is set very high to attribute and then prove responsibility. Prosecutors need to show that the attacks are not merely accidents or "collateral damage."

After the supermarket attack, Moscow said the missile was aimed at "hangars with armament and munitions delivered by USA and European countries at Kremenchug [Russian spelling] road machinery plant." On this point, most observers and investigators agree, Russia is lying. The facility in question is about a quarter of a mile (400 meters or 1,400 feet) from the supermarket. Russia claimed that the fire at the supermarket was caused by flying debris coming from the facility, but post-strike satellite imagery clearly shows a crater where the missile fell directly on a corner of the market.

Russia's claims in response to accusations of war crimes, including at the Kremenchuk supermarket, are almost comical. Apparently not content to say that Kremenchuk was a tragic accident, Russia's Deputy Permanent Representative to the United Nations Dmitry Polansky called the civilian deaths a "provocation" by Ukraine, a staged event. The claim harkened back to Russia's assertion that the civilian deaths in the town of Bucha, north of Kyiv, now established to be some 400, were manufactured by Ukraine: that Kyiv hired actors to play the civilians lying in the streets. The Bucha claims were grotesque—and in using the same playbook in Kremenchuk, Moscow's propagandists seemed to want it both ways, saying both that the supermarket was damaged in an attack on a legitimate military-related facility while also saying that the incident was staged.

Moscow further muddied the waters by claiming that the supermarket in Kremenchuk was "non-functioning" (closed), a claim that social media demolished. Yet Google maps do indeed label the market "temporarily closed" and the Google street view shows the parking lot empty in the middle of the day. Obviously Russian intelligence is relying on more than Google maps in choosing what to bomb, but there is some basis for Russia's claims, however disingenuous.

A number of investigations have debunked Russia's various propaganda talking points, but just because Russia is deceitful and craven in its explanations doesn't mean the attack was in fact a war crime. There is no question that Russia is responsible for the supermarket disaster (there is even closed-circuit TV from the scene that captured the descending missile) but was the supermarket actually targeted and intentionally struck? That turns out to be a difficult question to answer, because short of testimony from the Russian bomber crewmembers who delivered the missile, investigators must look to evidence on the ground, and to Russia's overall practices to see whether or not an attack on a supermarket fits into a pattern with other attacks.

A hospital in Vuhledar

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February, human rights monitors have been scrupulous in documenting Russian conduct. On the first day of attacks, for example, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch accused Russia of damaging a hospital in Vuhledar (aka Ugledar), a coal mining town 50 miles north of Mariupol in southeastern Ukraine.

At about 10:30 in the morning on February 24, a short-range Tochka missile (NATO SS-21 Scarab) landed in front of the Central City Hospital, killing four and injuring 10 civilians. Human Rights Watch focused on the missile's cluster bomb warhead with 50 submunitions, pointing out the international convention banning the use of such weapons.

Establishing the facts in this and other cases is a meticulous process: taking witness testimony, documenting who was involved, establishing the weapons used, the damage, and deaths and injuries to civilians. In this case, Human Rights Watch interviewed workers at the hospital and collected photographic evidence. A photo of the nose cone of the missile, widely posted on social media, was the basis for determining the type of weapon used.

Amnesty International said the Russian ballistic missile strike on the hospital was "verified" by its Evidence Lab. "The Russian military has shown a blatant disregard for civilian lives by using ballistic missiles and other explosive weapons with wide area effects in densely populated areas," said Agnès Callamard, the organization's Secretary General. "Some of these attacks may be war crimes."

But there is a major problem with that narrative. Tochka is owned by both Russia and Ukraine, and though observers seem content to assume that Russia attacked Vuhledar, U.S. intelligence says that Russia probably did not fire a Tochka missile until March 6— about a week into the war.

Ukraine, on the other hand, is known to have fired Tochka missiles on the first day against a target in Kirovske in occupied Donetsk. Over the next 72 hours, Ukraine fired more Tochkas at Russian forces and against two airbases located in Russia itself, one at Millerovo and the other at Taganrog. On March 1, Ukraine also hit a Russian naval ship docked in Berdiansk harbor with a Tochka missile.

That photo of the nose cone, the one that identified the weapon that landed in Vuhledar on February 24? There is no photographic evidence that places it in Vuhledar, nor is there anything that proves that it is Russian.

The town of Vuhledar, in context, also proves to be an unlikely target. The Ukraine General Staff did not report the town or its surroundings attacked until March 13, raising the question whether it was an intended Russian target on February 24, when all of Russia's long-range attacks were highly choreographed.

On March 11, the independent investigative collective Bellingcat stated that Vuhledar was the only "confirmed example of this particular cluster munition [type] being used" in Ukraine, further raising questions regarding who fired the missile that landed there. In other words, it was most likely a Ukrainian Tochka missile fired somewhere to the east, which failed in flight and landed in Vuhledar, causing the damage and deaths.

"Documenting and attributing weapons use during a conflict is difficult, especially when both sides are using many of the same types of weapons," Mark Hiznay told Newsweek. Hiznay is an arms researcher for Human Rights Watch who wrote the technical sections of the Vuhledar report. Newsweek reached out to the Ukrainian government for comment but did not receive a reply.

A holiday resort in Odesa

On the night of June 30, another Russian Kh-22 missile hit a multi-story apartment building and two "recreation centers" in the village of Serhiivka on the southern Black Sea coast. The attack killed 22 civilians and injured another 40, the largest number of victims among all Russian attacks in the Odesa region.

In his video address that night, President Zelensky denounced the Serhiivka strike as "conscious, deliberately targeted Russian terror and not some sort of error or a coincidental missile strike."

Russia responded with its usual misinformation. "In Odesa, the Kyiv regime is preparing another sophisticated provocation to accuse the Russian Armed Forces of killing civilians (including minors) and purposefully destroying civilian infrastructure," Russian Colonel General Mikhail Mizintsev said in a Kremlin press release. "All participants in the staged scenes after the video filming are provided with a cash reward in the amount of $500, while $100 have already been paid to each in advance," he said.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitri Peskov told reporters that the attack in Serhiivka was intentional, that Russia targeted an ammunition depot there. Amnesty International visited the location and said their organization found no evidence of the presence of Ukrainian soldiers, weapons, or other valid military targets nearby. "Satellite imagery reviewed by Amnesty International also did not indicate any military activity in the area prior to the attack," the organization said.

"We are doing our utmost to identify the perpetrators," tweeted then-Ukrainian prosecutor Iryna Venediktova. "Seized the missile fragments, took measurements to determine the flight path, obtained videos from surveillance cams."

But U.S. intelligence says there is a significant Ukrainian ammunition depot nearby, one that is clearly identifiable on satellite maps some 2.2 miles (3.53 km) away. None of the news reports mention the depot. The damage in Serhiivka was indeed the work of an errant missile: It is tragic, and Russia is to blame for using such obsolete weapons, but the aim was an attack on a legitimate military target.

The highly unreliable Kh-22 missile (NATO AS-4 Kitchen) that fell in the village is the same missile used in the supermarket attack in Kremenchuk. This 32-foot long missile, designed in the late 1950's, is intended for long-range attacks against naval vessels, specifically aircraft carriers. (A newer version, the Kh-32, used in Kremenchuk, was fielded in 2016.)

It is estimated, under the best of conditions, that a Kh-22 type missile will land within three miles of its intended target, while the updated Kh-32 should land somewhere within 1.5 miles of a desired aimpoint. After the Kremenchuk attack, British military intelligence reported that "these weapons are...unsuitable for precision strikes and have almost certainly repeatedly caused civilian casualties in recent weeks." The Kh-22 is responsible in Serhiivka, just as it was in Kremenchuk, but there is no evidence that the Russian attack on civilians was intentional.

International law finds "wanton destruction of cities, towns, or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity" a war crime. A recent United Nations report on war crimes found that "the level of civilian casualties and the level of damage to civilian infrastructure in each case...suggest numerous failures to take constant care to spare the civilian population, civilians and civilian objects in the conduct of military operations, and to take all feasible precautions in attack." But it stops short of accusing Russia of having committed war crimes in its bombing.

It isn't clear that technical failures (or gross inaccuracies) rise to a level to be considered "grave breaches" of international law. Using the Kh-22 missile in attacks on ground targets might be considered war crimes if Russian commanders or decision-makers were warned of the missile's inaccuracy and unreliability and chose to order their use anyway.

Are the bombings in Kremenchuk or Serhiivka war crimes? The answer is likely no. Such a conclusion might be infuriating: These attacks seem to join Mariupol and Bucha as heinous acts already labeled war crimes. Russians soldiers and their commanders have most certainly committed war crimes on the battlefield, but cases like Kremenchuk, Vuhledar or Serhiivka follow similar patterns—weapons that don't work and careless decisions, and sometimes just the bad luck of civilians being in harm's way in a total war. Newsweek reached out to the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense for comment about Serhiivka but did not receive a response.

The fog of war

Ukrainian military barracks and depots are located on the periphery of many cities and towns, and at least 10 of Ukraine's major airports are joint civilian and military facilities. Ukrainian forces, moreover, especially National Guard and territorial defense units, are operating from within urban areas. Air defense systems, especially in the Kyiv region, are deployed in built-up areas—necessary to defend the cities, but also placing more civilians in danger.

Ukraine is not to blame for its geography, of course, but it's inaccurate to apply the term "war crime" to any incident in which civilian objects are damaged or civilians are killed. The cascade of accusations rarely takes into consideration the realities on the ground where attacks have occurred. Take, for example, War Crimes Watch Ukraine, a collaboration between the Associated Press, Frontline, and PBS. The elaborate website says it documents "evidence of potential war crimes in Ukraine, including direct attacks on civilians and attacks on civilian infrastructure including hospitals, schools, residential areas and sites protected under international humanitarian law."

In one northern Ukrainian city, Zhytomyr, 80 miles (130 km) west of Kyiv, War Crimes Watch registers seven war crimes, two attacks on medical facilities, two on schools, two on cultural or religious sites and a "direct attack on civilians." New Direction, a conservative European non-profit, with its own list of Crimes in Ukraine Committed by the Russian Federation, lists one incident in Zhytomyr, the bombing of a church. The U.N. reports cites a number of incidents as potential war crimes, including the bombing of a children's hospital and a "maternity house," a city school, a bridge, and the civilian airport.

There were Russian attacks in all of these places, with numerous civilian deaths and significant damage. It's easy to assume that the city and its residents were the target of attack. But none of the accusations of war crimes mention that Zhytomyr is also a military town, home to the 95th Air Assault Brigade, Ukraine's Air Assault Command, two major military schools and the 199th Training Center, the 148th Artillery Battalion, a regional headquarters, and major National Guard and territorial defense units. Nearby is Ozerne airbase, home to the 39th Wing. Again: None of this excuses Russia, but labeling attacks in and around a city as war crimes without making reference to the likely intended targets creates a false or, at best, incomplete picture.

Since the beginning of the war, the Russian Ministry of Defense has regularly published details of Ukrainian forces deployed in or near hospitals and medical facilities. Newsweek's request to the Ministry for comment on those claims was declined, but the Russian embassy at the United Nations provided a military advisor to address the subject on condition of anonymity.

The advisor was quick to point out that the U.N. report on war crimes stated that "it also appears likely that Ukrainian armed forces did not fully comply with IHL [international humanitarian law] in eastern parts of the country." He repeatedly asserted that Russia had evidence of Ukrainian war crimes—shooting into civilian areas in Donbas, hiding in schools and hospitals, firing from residences.

Three weeks after Newsweek requested evidence of those alleged incidents, the Russian military advisor produced what he said was proof of such Ukrainian practices. He claimed the photos were taken in Severodonetsk on February 27, and that they show a Ukrainian artillery unit firing from a soccer field, as well as Ukrainian armored vehicles hiding near civilian buildings. Though the photos can be geolocated and appear genuine, it's important to note that the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense published one of the same pictures (also on February 27th) suggesting that it showed a Russian artillery unit. It has not been ascertained which side is telling the truth.

'Confused children'

Since the Russians withdrew from northern Ukraine, Kyiv has been burying the dead and counting the toll. The Kyiv area governor reports that the region has determined that 1,346 civilians have been killed in his region since the beginning of the war, with another 300 still missing. This region includes the town of Bucha, where 403 died, according to the latest estimate.

The State Emergency Service says that 700 of those who died in the Kyiv region were killed by small arms: in other words, shot by Russian soldiers. Another 300 are estimated to have died close to the battlefield in artillery strikes and as a result of tank fire. That means that between February 24 when Russia invaded and April 1 when the last Russian troops withdrew from the region, some 300 died as a result of missile strikes and bombing. For all of the news media attention to the capital city and its surroundings—attention that created the impression of intentional attacks on civilians—a small number were actually killed in the missile attacks and aerial bombing there: 110 in the city of three million and fewer than 200 in other areas of the province.

Bombing is the most observable and therefore the most frequently reported event in war, which creates the impression that it is not only the cause of most civilian casualties, but also the main cause. In fact it is the ground battle in Ukraine—the war beyond bombing and mostly taking place out of sight—that has been devastating, with rapes, torture, the intentional murder of civilians. Focusing on the wrong sources both fails to hold Russia (and Ukraine) fairly accountable while also missing the opportunity to learn how best to protect civilians in conflict.

In every one of the 25 bombing incidents that Newsweek examined, ambiguities and questions arose regarding the intended target, the weapon used, Ukraine's role, and Moscow's intentions. There is a possibility that all of them are war crimes, especially in cases of large numbers of civilian casualties relative to the military advantage gained in attacking even legitimate targets. But it comes down to individual cases, to determining the facts and assessing who is responsible.

"These are not warriors of a superpower," Ukrainian President Zelensky said at the beginning of the war, referring to Russian soldiers. "These are confused children who have been used."

Zelensky is not entirely wrong. The casualties of Russia's invasion include thousands of unprepared and misled Russian soldiers. Indeed the war's first convicted war criminal (condemned to life in prison) is an inexperienced 21 year old. Army Sergeant Vadim Shishimarin was captured and later accused of killing a 62-year-old civilian in northeastern Ukraine as his unit was moving through the small village of Chupakhivka on the first day of the war. The Ukrainian man, Shishimarin told the court, was using his cellphone and he and his comrades feared that he was reporting the location of his unit to authorities. He claimed he was ordered to shoot the man, which he did.

Shishimarin pleaded guilty, and in his statement to the court said that he "sincerely repented."

The panel of judges found Shishimarin guilty of "violation of the laws and customs of war, connected with premeditated murder" and handed down a life sentence. The chief judge said the young man had committed "a crime against peace, security, humanity and the international legal order" and that only a life sentence was appropriate.

"I was nervous at the time. I did not want to kill," Shishimarin said in his final statement. "It's just how it happened."

About the writer

William M. Arkin is an award-winning journalist and best-selling author of more than a dozen books on national security issues. ... Read more