An additional 896 hectares of land in Siem Reap have been allocated to expand a second relocation site for the thousands of families being removed from the Angkor Archaeological Park, according to a December sub-decree signed by Prime Minister Hun Sen released publicly in the Royal Gazette on May 17.

The newly allocated land for the relocation site, on top of the current 514 hectares granted to house displaced families, is spread across Peak Sneng, Svay Chek and Leang Dai commune in the Angkor Thom district.

Peak Sneng’s commune chief said 3,500 families were expected to arrive beginning in July at the new relocation site in his commune, while the other two commune chiefs said they did not have clear information.

Since October last year, the government has attempted to relocate around 10,000 families who it claims have been living illegally inside the Angkor Park to two different relocation sites.

Amnesty International told CamboJA that it was concerned the expansion of the second relocation site would lead to more “forced evictions” from the Angkor complex to an area that may not be properly equipped for their arrival.

One farmer in Peak Sneng told CamboJA he was “forced” to accept significantly less land in an unknown location to make way for the expanding relocation site, complaints echoed by at least 12 other families according to commune chief Sok Sea.

Long Kosal, a spokesperson for the APSARA Authority, which oversees the Angkor complex, told CamboJA that the second Angkor relocation site needs to be expanded to accommodate more families.

Kosal claimed that nobody would be negatively affected by the relocation site’s expansion and that “voluntarily” relocated families would receive 20 by 30 meter plots of land, as the thousands of families sent to the Run Ta Ek site received.

Kosal said that families had not yet been relocated to Peak Sneng because the government was still setting up infrastructure, such as water, electricity and roads, to allow families to live there. He said he did not know how many families would be sent to the site, but that authorities would be prepared.

“We have thought about every possibility before doing anything,” Kosal said. “We don’t carry out any work that has a [negative] impact on individuals.”

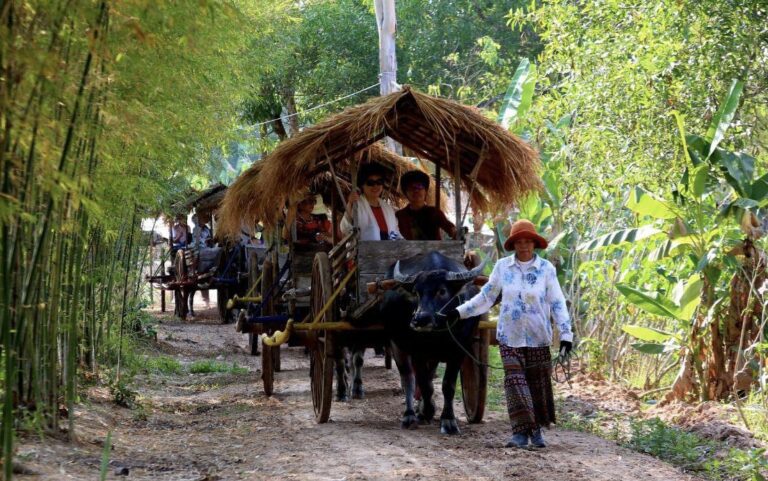

An April CamboJA investigation found many families sent to the first relocation site — in Siem Reap’s Run Ta Ek commune — felt they had no choice and lacked basic necessities such as shelter, water and economic opportunities when they arrived.

A Peak Sneng commune resident in a village of the same name said that he was not satisfied with the five 20 by 30 meter plots of land he received two months ago from authorities in exchange for 1.5 hectares of his farmland, which would be used as a relocation site.

Khnou Sovann, 51, said he was “forced” to exchange his farm for only 0.3 hectares of land in an unknown location elsewhere in the commune.

“They forced us,” Sovann said. “They could give us only five lots of land. If we demand more, they will not give it. No matter how dissatisfied we may be, we must accept it.”

Authorities gave him a letter saying he had accepted the exchange but did not specify when he would have to leave. While still currently able to use his farm, Sovann said still does not even know if the five plots of land he will receive in the future will be connected.

“We asked for five plots in a row but do not know if we were given land in a row,” he said. “If it is not, we cannot farm it. It affects our livelihood. We earn money to pay the bank and farm for food.”

Amnesty International has described the relocation from inside the Angkor complex as “forced evictions in disguise” — a characterization UNESCO and the Cambodian government have denied.

Some farmers on land re-allocated to accommodate Angkor families have also said they are not being compensated fairly. In April, CamboJA spoke with a farmer in Peak Sneng who said he had lost 15,000 square meters of land and received only around 3,000 square meters in an unspecified location as compensation from authorities.

Peak Sneng commune chief Sea said that in his commune there are still 12 families who have not accepted the land exchanges offered by authorities, in which they would receive two 20 by 30 meter plots — 0.12 hectares — for their one hectare farms.

Their cases have been sent to the provincial level, but lack resolution, Sea said. He added that if they still refuse to accept they may not receive any land.

Provincial governor Tea Seiha could not be reached for comment.

Koeun Kep, the head of the Leang Dai commune, said that he had not yet been informed about the clearing of nearly 900 hectares of land in his commune.

Chhuon Em, chief of Svay Chek commune, said that only one family remains in his commune that cannot be resettled, and that case was sent to district level.

This family is not satisfied with the compensation they are receiving because the land being taken from them is a lot, he added. The family could not be reached for comment, but several families living in Svay Chek said they were unaware of land in the commune being reallocated to new families.

A representative for human rights NGO Licadho in Siem Reap said he has not yet received information on the expansion of nearly 900 hectares in the three communes. But he said that prior issues with existing families impacted by the 514 hectares re-allocated to house new families have since been resolved.

Prime Minister Hun Sen has said the mass displacement is intended to appease UNESCO and allow the park to remain classified as a World Heritage site.

UNESCO, which exerts significant influence in managing the Angkor complex, has publicly denied involvement in the relocations, even as it has repeatedly urged for the removal of “illegal structures” around the Angkor temples.

“As UNESCO has clarified on many occasions, UNESCO and the World Heritage Committee are not parties to this relocation program and have not made any request for population relocation to the Cambodia authorities,” a UNESCO spokesperson said in an email to CamboJA received Thursday.

UNESCO said its Phnom Penh office has been reassured by the Cambodian government that sustainable development and human rights principles will be upheld. UNESCO said the government had clearly communicated its compensation plans for families affected by the relocation program.

On March 22, UNESCO also requested the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, which manages APSARA, to “provide additional information on the relocation issues” at Angkor.

UNESCO added that it would “bring all relevant information” such as “public reports” and “third-party information” to share with the World Heritage Committee, a group of representatives from 21 states which will meet in September to review the status of the Angkor park.

“Under the mechanism of the 1972 UNESCO Convention, it will be for Member States of the Committee to assess the situation and take any appropriate decisions,” Unesco’s spokesperson said.

Joe Freeman, Amnesty’s interim deputy regional director for communications, expressed concern in an emailed statement to CamboJA, that the expansion of the second relocation site could lead more people to be resettled in conditions similar to the Run Ta Ek site.

“Many are now in debt because they don’t have jobs or fully built houses when they arrive at resettlement sites,” Freeman said. “Our research shows that the government does not have appropriate safeguards against forced evictions as per international human rights standards, including the lack of adequate notice prior to evictions, and genuine consultation with affected people on the evictions and resettlement process.”

Families sent to the Run Ta Ek relocation site have received corrugated iron sheets, $300 in cash, ID Poor cards, a mosquito net, a tarpaulin sheet and two months’ food supplies, Amnesty International has reported.

Amnesty International called for authorities to ensure relocated residents at both sites were provided with adequate housing, access to sanitation, fair compensation and employment opportunities.

“In its current state, the Run Ta Ek resettlement site is not habitable and we have called on the government to stop evicting people to the site,” the spokesperson said.

While infrastructure has improved at Run Ta Ek in the months after families first arrived, Kim Kary, 54, who was relocated to Run Ta Ek in late February, told CamboJa that she still cannot earn a living there.

“I cannot sell any food,” she said. “I cannot earn money. It’s so quiet. I only stay at home.

“I can get a little support because I have an ID Poor card,” she added. “Yet now I have only expenses and no income.”