7 Powers: Foundations of Business Strategy (Key Takeaways)

Moats are those barriers that protect your business margins from the erosive forces of competition. It doesn’t matter how revolutionary your product is: even if it literally changed the face of human civilization, you’re going to get nothing for it if anybody can sell it too, arbitraging profits away. The whole surplus of the revolution will go to the consumer, and none to you.

There are some key terms defined in the book 7 Powers.

- Strategy (capital S): The study of the fundamental determinants of potential business value.

- Power: The set of conditions creating the potential for persistent significant differential returns, even in the face of fully committed and competent competition.

- strategy (small s): A route to continuing Power in significant markets.

Strategy (capitalized S) is distinguished from strategy (lowercase s) and is divided into Statics (or “being there”) and Dynamics (or “getting there”).

- Strategy Statics: ‘Being There’. What makes a business so valuable for so long?

- Strategy Dynamics: ‘Getting There’. What developments yielded this attractive state of affairs in the first place?

Power is the core concept of Strategy, and the book explains what it looks like when a company has power (Statics) and how a company can get power (Dynamics).

4. Benefit: The way in which the power improves cash flows, such as through lower costs or the ability to charge higher prices and/or decreased investment requirements. Aka the magnitude aspect of power.

5. Barrier: The way that competitors are prevented from arbitraging the benefit of power. Aka the duration aspect of power.

Each power creates a benefit for the winning company and a barrier for its competitors. A benefit is common, but a barrier is rare.

Benefits are common, and they often bear little positive impact on company value, as they are generally subject to full arbitrage. The true potential for value lies in those rare instances in which you can prevent such arbitrage, and it is the Barrier that accomplishes this. Thus, the decisive attainment of Power often syncs up with the establishment of the Barrier.

If your business does not have at least one of the 7 Power types, then you lack a viable strategy, and you are vulnerable.

Part 1: Statics — Defining the 7 Powers

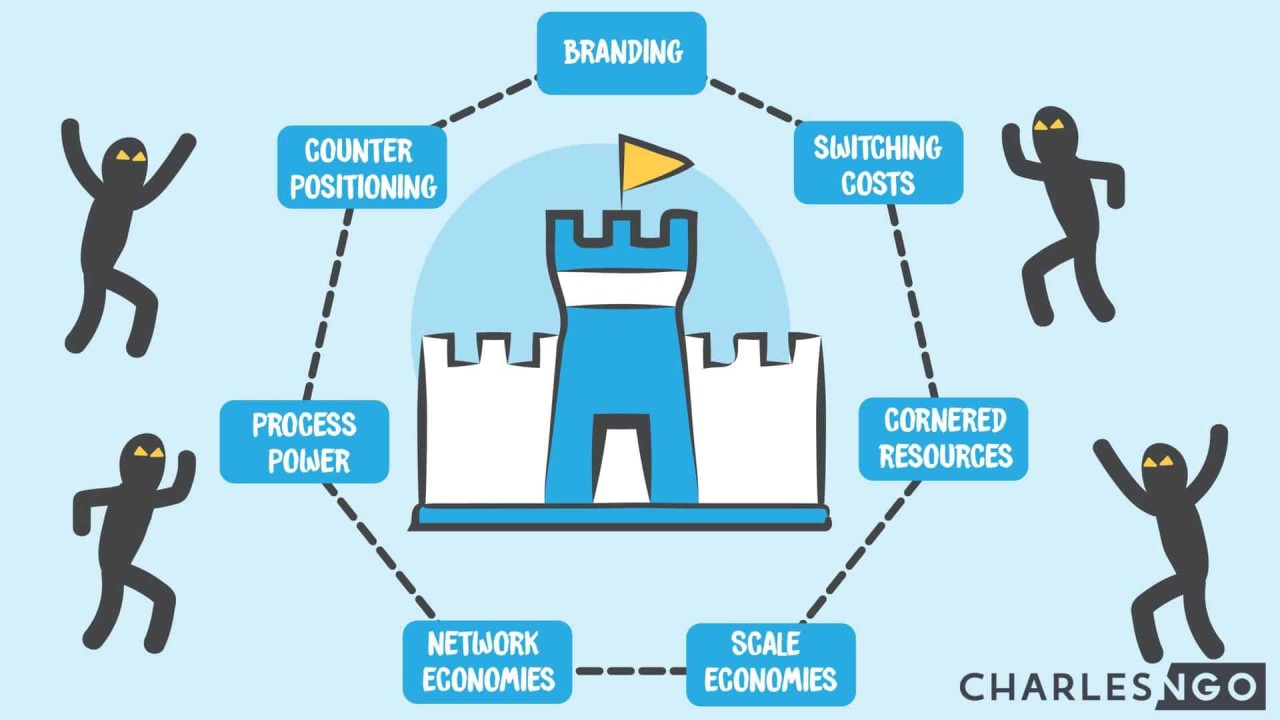

The 7 Powers are:

- Scale Economies

- Network Economies

- Counter-Positioning

- Switching Costs

- Branding

- Cornered Resource

- Process Power

Power 1: Scale Economies - A business that leverages scale economies sees its per-unit cost decline as production volume increases.

Benefit - Reduced Cost

Barrier - Prohibitive Costs of Share Gains

Example - One pivotal strategic moment for Netflix was its investments in originals. Netflix's traditional streaming service put it in a precarious strategic position as it had to continually license content from owners, pay licensing fees based on consumption, and renegotiate those deals every few years on a case-by-case basis. This not only limited Netflix's margins but also allowed any competitor to strike similar deals with content owners, preventing them from establishing a moat.

Netflix completely changed the game, though, as they moved to develop original content, like House of Cards in 2012. The original content strategy was a great example of scale economies, as they paid an upfront price for the content, which allowed them to reduce their costs and increase their margins on a per-subscriber basis as they added more and more subscribers. A challenger looking to compete with Netflix's original content would not only have to be able to make the large initial outlay to produce original content but would also suffer from higher per-subscriber costs with a far smaller base of users to spread those costs amongst. Even if a challenger attempted to gain share by eating some of the cost, Netflix could leverage its superior cost advantage to then undercut the competition. So you can see how Netflix moving to original content not only significantly improved its margins but also established a compelling moat preventing competitors from easily emulating it.

Being #1 pays, especially in those industries with very low marginal costs. Suppose you’re Netflix. You have 100M subscribers, and each original costs $100M — so, $1 per subscriber. Now, consider your competitor Hulu, with 20M subscribers. Delivering the same value as Netflix costs them $5 per sub, 5 times as much! That means that you can allow yourself to spend more on marketing; better content; superior user experiences; more experienced people; and even be less efficient and still beat them. If Hulu tries to remediate this by offering less content or raising prices, customers will abandon their service and they will lose the market share.

Example - Salesforce (or any SaaS company). The cost to develop software is (mostly) fixed. For each additional customer acquired, the development cost per user decreases.

Beyond fixed costs, Scale Economies can emerge from other sources as well.

- Volume/Area Relationships - When production costs are tied to a geographical area, and utility is tied to volume, resulting in lower per-volume costs with increasing scale. eg Amazon fulfillment centers, Bulk milk tanks.

- Distribution Network Density - The more customers in a distribution network, the cheaper the delivery costs. eg UPS or DHL.

- Learning Economies - When learning leads to benefits, which is, in turn, is positively correlated to production levels.

- Purchasing Economies - Larger scale buyers get better deals. eg Walmart, Tesco.

Power 2: Network Economies - A business that leverages network economies sees that the value of a product to a user increases as new users join the network. In such a situation, having the most customers is everything,

Benefit - Ability to charge higher prices than the competitors, because of the higher value as a result of more users.

Barrier- Unattractive cost/benefit of gaining share. How much cheaper do you have to make your network for it to become the preferred choice?

Example - LinkedIn, the professional network, is a canonical example of a service benefiting from network economies. As the user base grows, users are able to connect with more of their existing colleagues, search and find more people of interest, and apply for more jobs. Recruiters, the primary source of LinkedIn's monetization, can also find more relevant candidates as the member base increases. But most importantly, these strong network effects have made it nearly impossible for anyone to compete with a generalized professional network. The prospect of joining an alternative network that most of your colleagues aren't already using deteriorates the potential value of the alternative, regardless of whether it offers significantly improved functionality. This strength of network effects often leads to a winner-take-all dynamic in industries where network effects are present.

Example - Windows. More users lead to more developers writing software, which made the platform more useful to additional users, attracting more developers, etc…

Example - Facebook is the best example. Technically superior social networks might come and go, but people don't switch because "all their friends are on Facebook."

Industries exhibiting Network Economies often exhibit these attributes:

- Winner takes all - Businesses with strong Network Economies are characterized by a tipping point: once a single firm achieves a certain degree of leadership, then the other firms just throw in the towel. For example - Even a company as competent and with as deep pockets as Google could not unseat Facebook with Google+.

- Boundedness - It is well demonstrated by the continued success of both Facebook and LinkedIn. Facebook has powerful Network Economies itself but these have to do with personal, not professional interactions. The boundaries of the network effects determine the boundaries of the business.

- Decisive early product - Due to tipping point dynamics, early relative scaling is critical in developing Power. Who scales the fastest is often determined by who gets the product most right early on. Facebook’s trumping of Myspace is a good example.

Power 3: Counter Positioning - A business that leverages counter-positioning adopts a new, superior business model that the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business.

Benefit - The new business model is superior to the incumbent’s business model due to lower costs and/or the ability to charge higher prices.

Barrier - Reaction will lead to collateral damage to existing business

The incumbent’s failure to respond, more often than not, results from thoughtful calculation. They observe the upstart’s new model, and ask, “Am I better off staying the course, or adopting the new model?” Counter-Positioning applies to the subset of cases in which the expected damage to the existing business elicits a “no” answer from the incumbent. The Barrier, simply put, is collateral damage. In the Vanguard case, Fidelity looked at their highly attractive active management franchise and concluded that the new passive fund’s more modest returns would likely fail to offset the damage done by migration from their flagship products.

What are the potential causes of such decrements? They could be numerous, but two of them seem common. The first involves two characteristics of challenges to incumbency:

- The challenger’s approach is novel and, at first, unproven. As a consequence, it is shrouded in uncertainty, especially to those looking in from the outside. The low signal-to-noise of the situation only heightens that uncertainty.

- The incumbent has a successful business model. This heritage is influential and deeply embedded, as suggested by Nelson and Winter’s notion of “routines,” and with it comes a certain view of how the world works. The CEO probably can’t help but view circumstances through this lens, at least in part. Together these two characteristics frequently lead incumbents to at first belittle the new approach, grossly underestimating its potential.

Five stages of counter positioning

- Denial

- Ridicule

- Fear

- Anger

- Capitulation (frequently too late)

Example - Vanguard and its assault on the world of active equity investing with its low-cost passive index fund approach is a great example of counter-positioning. While today we can easily appreciate the merits of passive investing, at the time Vanguard introduced the model it was a highly contrarian approach. So many were skeptical about why would someone just accept the average returns of the market instead of choosing active funds designed to beat the market. What we all now know is just how rare it is for actively managed funds to continually beat the market. And Vanguard saw its assets under management grow as more and more investors saw promise in the passive approach. The reality though was it would have been easy for a competitor to introduce their own low-cost passive index funds, as there wasn't anything technically preventing them from doing so. Yet they were extremely slow to do so. Fidelity, a leading incumbent at the time, was well aware of Vanguard's approach but continually concluded that introducing low-cost passive indexes would significantly cannibalize the fees they enjoyed on their actively managed funds and would fly in the face of the better-than-average returns they promised in their flagship active funds. So at every turn, Fidelity actively decided against taking Vanguard head-on. Even when Vanguard continued to see significant traction, Fidelity only dabbled lightly in the space out of fear of affecting its core business, allowing Vanguard to solidify its leadership position in the market.

Example - Netflix charging no late fees where late fees made 50% of Blockbuster revenues. Blockbuster couldn’t respond.

Example - Another example of counter-positioning is what digital cameras did to Kodak. Kodak’s business model was legendary, built on the customer’s continuing need to purchase the film, a product in which Kodak was wildly profitable due to both Scale Economies and a proprietary edge.

When digital photography came along and analog chemical film doomed, everyone chided Kodak for poor management, lack of vision, and organizational inertia and a reasonable person might well ask, “ How could a company high on the lists of the best companies in the world succumb to such a defeat?”

Kodak was fully aware of its eventual fate and spent lavishly to explore survival options, but digital photography was not an attractive business opportunity for the company.

Kodak's business model was built on its Power in the film - it was not a camera company. The digital substitute for the film was semiconductor storage, and Kodak brought nothing to this arena. As a company Kodak had excellent management; thus the observed wheel spinning, the fruitless exploration in the digital world simply reflected the strategic challenge they faced. The technological frontier had moved: consumers were better off, but Kodak was not.

More generally this situation can be characterized by three conditions:

- A new superior approach is developed (lower costs and/or improved features).

- The products from the new approach exhibit a high degree of substitutability for the products from the old approach. In this case, as semiconductor topologies shrunk, digital imaging came to completely supplant chemical imaging.

- The incumbent has little prospect for Power in this new business: either the industry economies support no Power or the incumbent’s competitive position is such that attainment of Power is unlikely. Kodak’s formidable strengths had little relevance to semiconductor memory and those new products were on an inevitable path to commoditization.

Power 4: Switching Costs - A business that leverages switching costs causes its customers to incur a value loss from switching to an alternate supplier for additional purchases.

Switching costs arise when a consumer values compatibility across multiple purchases from a specific firm over time. These can include repeat purchases of the same product or purchases of complementary goods.

Switching costs can be divided into three broad groups:

- Financial - Financial Switching Costs include those which are transparently monetary from the outset. For ERP, these would include the purchase of both a new database and the sum total of its complementary applications.

- Procedural - Procedural Switching Costs stem from the loss of familiarity with the product or from the risk and uncertainty associated with the adoption of a new product. When employees have invested time and effort to learn the particulars of how to use a certain product, there can be a significant cost to retraining them in a different system.

- Relational - Relational Switching Costs are those tolls that would result from the breaking of emotional bonds built up through the use of the product and through interactions with other users and service providers. Often a customer establishes a close relationship with the provider’s sales and service teams. Such familiarity, ease of communication, and mutual positive feelings can create resistance to the prospect of severing those ties and switching to another vendor.

Benefit - A company that has embedded Switching Costs for its current customers can charge higher prices than competitors for equivalent products or services.

Barrier - To offer an equivalent product, competitors must compensate customers for Switching Costs. The firm that has previously roped in the customer, then, can set or adjust prices in a way that puts their potential rival at a cost disadvantage, rendering such a challenge distinctly unattractive.

Example - Traditional on-premise software, like SAP's ERP solution leveraged by many enterprises, is a classic business that benefits from switching costs. The initial implementation of SAP is expensive, not only from a dollar perspective but typically because of heavy investment in customizing the platform to handle a company's unique workflows as well as the significant training to get the team up-to-speed on how to leverage the sophisticated software. The prospect of ripping out the solution and replacing it with an alternative becomes both an expensive and daunting proposition, encouraging customers to stick with their existing solution even when an alternative becomes available promising superior functionality.

Example - Gmail. You’ve already given your email address to all your friends and used it to sign up for hundreds of services. Gmail’s UI isn’t bad enough to justify the hassle of switching all this.

Example - Photoshop, or complicated tools in general. In this case, the customer lock-in rests in the sunk cost of mastering a complex tool and learning its idiosyncrasies.

Power 5: Branding - A business that leverages branding enjoys a higher perceived value to an objectively identical offering that arises from historical information about the seller.

Branding is an asset that communicates information and evokes positive emotions in the customer, leading to an increased willingness to pay for the product.

There is a positive feedback loop at play with brands and distribution channels. The more people know your brand, the more they expect to see it on the shelves of their favorite store, giving you more leverage over it. That allows you to get better deals with these stores — which, in turn, act as a channel for people to discover your brand, furthering its reputation, etc…

Benefits - A business with Branding is able to charge a higher price for its offering due to one or both of these two reasons:

- Affective Valence - The built-up associations with the brand elicit good feelings about the offering, distinct from the objective value of the good. (eg Coca Cola is preferred to store brand's Cola, irrespective of flavor)

- Uncertainty Reduction - A customer attains “peace of mind” knowing that the branded product will be as just as expected. (eg People thinking that coffee will be OK at Starbucks)

Barriers - A strong brand can only be created over a long period of reinforcing actions (hysteresis), which itself serves as the key barrier.

Efforts to mimic another brand run the risk of trademark infringement actions as well with their attendant cost and unclear outcomes.

Example - Tiffany's jewelry is a classic example of a brand that has become a standard for wealth and luxury. Customers are willing to pay a hefty premium for the same diamonds they could find elsewhere. Tiffany was able to achieve this initially through a strong focus on silver craftsmanship, winning numerous awards for its high-quality jewelry, as well as inventing the now-classic Tiffany setting. But in addition to their focus on product quality, they also carefully curated their image. Take their signature Blue Box that all their jewelry comes in. Any woman can quickly recognize when they have been gifted Tiffany's because of it. Tiffany has cultivated its brand name for more than a century. It's no wonder Tiffany's to this day commands a significant margin premium over modern alternatives like the Blue Nile.

Power 6: Cornered Resource - A business that leverages a cornered resource has preferential access at attractive terms to a coveted asset that can independently enhance value.

Resources can be material as well as human: some firms have gotten so good at acquiring and retaining extremely educated talent from microscopic pools that one could argue they’ve effectively cornered that market - like Google with AI PhDs.

Benefit - Produces uncommonly appealing product

Barrier - Unacquirable commodity

It’s easy to fool yourself into thinking you have a cornered resource.

To qualify, it needs to pass these five screening tests.

1) Idiosyncratic - It repeatedly generates returns

2) Non-arbitraged - The price paid does not exceed the additional profit

3) Transferable - It could create the same returns at another company

4) Ongoing - The resource creates benefits over a long period of time

5) Sufficient - The resource must be sufficient to create continued differential returns.

Example - The Cornered Resource can emerge in varied forms, offering uniquely different benefits. It might, for example, be preferential access to a valuable patent, such as that for a blockbuster drug; a required input, such as a cement producer’s ownership of a nearby limestone source, or a cost-saving production manufacturing approach, such as Bausch and Lomb’s spin casting technology for soft contact lenses.

Example - A more unique example of this is Pixar, which has enjoyed an absolutely astonishing record in the movie business, releasing hit after hit, which is incredibly rare in the movie business. Their first 10 films had an average Rotten Tomatoes score of 94%, 8 Pixar films have been awarded an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, and two have been nominated for Best Picture. What was the cause of this extreme performance?

Central to their success were the three founders of Pixar, who formed the core of the Brain Trust at Pixar. This included Steve Jobs, the visionary and brilliant entrepreneur, Ed Catmull, a pioneer CGI computer scientist, and John Lasseter, the animation genius. They each were the masters of their domains, with John on creative, Ed on technical, and Jobs on business and finance with implicit trust for each other. What prevented others from just hiring one of them away? Nothing short of extreme loyalty to each other. While many others tried to replicate Pixar's success they were never able to do so in such a sustained way. It ultimately led to Disney realizing its only option was to acquire Pixar, which it did in a $7.4B acquisition.

Example - Intellectual property, like Disney’s on their characters, or Apple’s on iOS

Power 7: Process Power - A business that leverages process power has embedded company organization and activity sets that enable lower costs and/or superior products and which can be matched only by an extended commitment.

Benefit - A company with Process Power is able to improve product attributes and/or lower costs as a result of process improvements embedded within the organization.

Barrier - The Barrier in Process Power is hysteresis: these process advances are difficult to replicate, and can only be achieved over a long time period of sustained evolutionary advance.

Example - Toyota is probably the most famous example of exhibiting process power by developing its now renowned Toyota Production System. The TPS was a superior automobile manufacturing process that resulted in both higher quality as well as far more durable vehicles. American car manufacturers couldn't compete, even when they tried to become well-versed in the methodology that Toyota was using. Ultimately there was so much nuance in the Toyota way and it extended beyond their own four walls to the way they sourced from suppliers, even bringing some of their methodologies to those suppliers. The sophistication of the process was critical in it being a powerful barrier that ultimately allowed Toyota to compete so effectively against American car manufacturers and to grow its share.

Note: I learn by reading from different sources and noting down the key takeaways. This article is also part of my notes. If you find any errors or if you have any feedback, please let me know.

References

https://www.sachinrekhi.com/7-powers-hamilton-helmer

https://florentcrivello.com/index.php/2018/07/29/mind-the-moat-a-7-powers-review/

Optimizing the Supply Chain

1yYehudah Schwartz the best summary of the book 7 powers. Well done Nikita Maloo