This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On a bleak St. Patrick’s Day in 2020, with holiday festivities canceled as COVID-19 swept across the U.S., Lawrence Abrams sent messages to ten of the largest ransomware gangs in the world. Stop attacking hospitals and other medical facilities for the duration of the pandemic, he pleaded. Too many lives were at stake.

As the founder and owner of the most influential news website dedicated to ransomware, Abrams was one of the few people with the connections and credibility to make such a request. His site, BleepingComputer, was one part demilitarized zone, one part neighborhood pub: a place where victims, media, law enforcement, cybersecurity buffs, and criminals all mixed.

Ransomware is one of the most pervasive and fastest-growing cybercrimes. Typically, the attackers capitalize on a cybersecurity flaw or get an unsuspecting person to open an attachment or click on a link. Once inside a computer system, ransomware encrypts the files, rendering them inaccessible without the right decryption key — the string of characters that can unlock the information. In recent years, hundreds of ransomware strains with odd names like Bad Rabbit and LockerGoga have paralyzed the computers of companies, government offices, nonprofit organizations, and millions of individuals. Once they have control, the hackers demand thousands, millions, or even tens of millions of dollars to restore operations.

Concentrated in countries such as Russia and North Korea, where they appear to enjoy a measure of government protection, the attackers are often self-taught, underemployed tech geeks. When Abrams wrote to them, he appealed to them as ordinary, decent people with parents, children, and partners they loved. How would you feel, he asked, if a member of your family were infected with COVID and couldn’t receive lifesaving treatment because the local hospital was hit by ransomware?

The next morning, Abrams awoke to a flurry of replies. Responding first, the DoppelPaymer gang agreed to his proposal, saying that its members “always try to avoid hospitals, nursing homes … not only now.” If they hit a hospital by mistake, they would “decrypt for free.”

Still, realizing that Abrams would make its pledge public on BleepingComputer, DoppelPaymer warned other victims against posing as health-care providers to avoid paying a ransom: “We’ll do double, triple check before releasing decrypt for free.”

As if it were a legitimate tech company, the Maze gang followed the well-worn corporate-PR strategy of circumventing the media and addressing the public directly. “We also stop all activity versus all kinds of medical organizations until the stabilization of the situation with virus,” it wrote on its dark-web site.

More followed suit. “We work very diligently in choosing our targets,” one group messaged Abrams. “We never target nonprofits, hospitals, schools, government organizations.”

Gathering the responses, Abrams wrote an article for BleepingComputer under the headline “Ransomware Gangs to Stop Attacking Health Orgs During Pandemic.” Its lead art was a rendering of a dove interlaced with an EKG readout forming the word PEACE in capital letters.

Undercutting this optimism, the NetWalker gang spurned Abrams’s proposal. Ignoring numerous examples to the contrary, NetWalker insisted that no ransomware group would hack into a hospital. But if “someone is encrypted” by accident, the group continued, “then he must pay for the decryption.” From Ryuk, a Russia-based gang that had been rampaging for a year and a half, Abrams heard nothing.

Still, he was satisfied. He felt that he was helping frontline workers and COVID patients and that he was right to have faith in the hackers’ humanity: “For the most part, they all resoundingly said, ‘We will not target health care.’ ”

Sarah White, who had spent years helping Abrams battle ransomware gangs, wondered if he had been gulled. “It was a good idea, but you can never trust a threat actor’s word,” she said.

Aaron Tantleff, a Chicago lawyer who advised ransomware victims, including medical facilities, during the pandemic, read Abrams’s article and discussed it with colleagues and clients. “In my mind, this was hysterical,” he said. “Hackers with a heart of gold.”

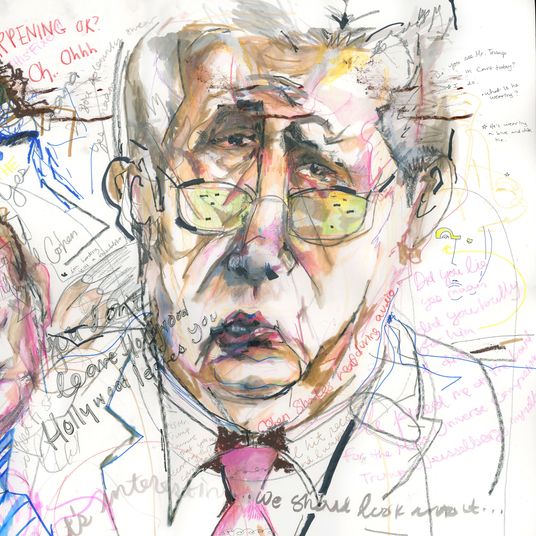

Abrams is in his early 50s with broad shoulders, a ruddy face, and graying hair. He lives with his wife and twin teenage sons in the New York area, where he grew up. From a young age, he was drawn to computers; he got his first one in second grade and was soon playing video games and preparing accounting spreadsheets for his friends’ parents. As a teenager, he browsed virtual bulletin boards, where he learned cybersecurity tips and was intrigued by the early hackers who lurked there. There was a “mystique about hackers and cybercriminals and cyberattacks,” he said.

After graduating from Syracuse University with a degree in psychology, he joined a Manhattan computer-consulting business, where he fixed IT problems for publishing houses, accounting firms, and Diamond District stores. Sitting at his office desk one day in 2002, Abrams read an article about somebody who had set up a fake server, a “honeypot,” to lure hackers in order to observe their tactics.

Curious, Abrams created his own honeypot, and a short time later someone broke into his virtual machine. He was amazed to be watching a hack in real time and couldn’t resist the urge to engage with the hacker. He opened Notepad and wrote a message to let the hacker know he was watching. He pressed ENTER and the cursor blinked on the next line. To Abrams’s wonder, the hacker wrote back, “What are you doing?” “Well, I just set this up,” Abrams typed. The two continued to banter. It was “a very bizarre experience,” Abrams said. “He found it amusing. I found it amusing. He wasn’t doing any damage. He was very amicable.”

In 2008, after four years of working on BleepingComputer as a side project, Abrams quit his consulting job to devote himself to the site full time. As traffic grew, he hired three staff reporters, but Abrams covered cybersecurity himself and developed contacts among both white- and black-hat hackers. His talent was in spotting the next big cybersecurity challenge, identifying the most promising people to work on it, and pulling them into his orbit.

That’s exactly what he did as ransomware emerged as a major threat. Victims began flocking to BleepingComputer’s forums, where they begged for help in recovering their files. A coterie of researchers responded, cracking the codes that had locked victims’ documents and photos and developing free tools for them to regain access without paying the attackers.

In 2016, Abrams helped organize the most dedicated of these volunteers, spread across the U.S. and Europe, into what became known as the Ransomware Hunting Team. This invitation-only band of about a dozen tech wizards in seven countries soon proved indispensable to victims who couldn’t afford, or refused out of principle, to pay ransoms to cybercriminals. Without charging for its services, the team has cracked more than 300 major ransomware strains and variants, saving an estimated 4 million victims from paying billions of dollars in ransom. Abrams functions as the team’s project manager and publicist, chronicling his collaborators’ achievements in his BleepingComputer posts.

Over the years, though, the gangs have gotten savvier and their cryptography has improved — partly owing to the pressure put on them by Abrams and his team. When the hunters identified a flaw and began supplying keys to victims, attackers would notice a slowdown in ransom payments. Realizing they had been outwitted, they would find and fix the flaw and make the strain tougher or impossible to decode.

As the pandemic forced businesses, schools, and nonprofit organizations to operate only online, making them more vulnerable to multimillion-dollar ransomware demands, the team was busier than ever. One weekend, Michael Gillespie, a 29-year-old from suburban Bloomington, Illinois, who had begun working with Abrams even before the team was officially formed, solved three types of ransomware. One invoked the pandemic in its name — DEcovid19 — and ransom note. “I am the second wave of COVID19,” the note said. “Now we infect even PC’s.”

On March 18, 2020, the same day that Maze promised to “stop all activity versus all kinds of medical organizations,” the group posted the personal data of thousands of former patients of Hammersmith Medicines Research, a London company that had refused to pay ransom. Hammersmith ran clinical trials for drug companies and later would test a coronavirus vaccine. When Abrams sought an explanation, the hackers said they had attacked Hammersmith on March 14, prior to the truce. “They basically said, ‘We locked them before this. We have not broken our pledge. This is not a new victim,’” he said.

Abrams urged them to take down the data, but they refused. On BleepingComputer, he acknowledged that the Hammersmith attack had raised doubts about the hackers’ commitment to the truce. “We will have to see if they keep this promise, which to most has already been broken,” he wrote.

Only direct patient care was off-limits for Maze. Once, the gang ensnarled the computer network of a small U.S. hospital’s parking system. The infected files contained data such as key codes that doctors and nurses used to drive into the garage. When the hospital requested a free decryptor, citing the truce, Maze balked. Because the files weren’t crucial, the hospital rejected the $35,000 ransom demand. Insurance covered the remediation costs.

Maze’s narrow interpretation of the truce set the pattern. Over the ensuing months, the gangs mostly abided by its letter — but not always its spirit. For example, they continued to target manufacturers of medicines and equipment vital to treating COVID patients. They rejected Abrams’s request for a cease-fire on drugmakers, whom they scorned as profiteers exploiting the crisis. The pharmaceutical industry “earns lot of extra on panic nowdays, we have no any wish to support them,” DoppelPaymer wrote.

DoppelPaymer, which had been the first gang to accept Abrams’s proposal, attacked Boyce Technologies, Inc., a company producing 300 ventilators a day for desperately ill COVID patients in New York hospitals. The gang encrypted Boyce’s files and posted stolen documents such as purchase orders.

Beyond drawing such fine distinctions, the truce participants were bound to make mistakes. In September 2020, DoppelPaymer paralyzed 30 servers at University Hospital in Düsseldorf, Germany, forcing the cancellation of outpatient and emergency services. The gang, which apparently had intended to hit the affiliated Heinrich Heine University, provided a free decryptor. Still, some things can’t be undone. After being redirected to a hospital 20 miles away, delaying her treatment for an hour, a 78-year-old woman died. As panic spread throughout Western Europe, authorities weighed charging the hackers with negligent homicide.

“She may have died due to the delayed emergency care,” a senior public prosecutor in Cologne said. German authorities ultimately closed the investigation, unable to prove that timelier treatment would have saved her life.

Truce participants did try, however half-heartedly, to leave patient care alone, but other gangs that had rebuffed or ignored Abrams’s overtures routinely assaulted hospitals and health services.

Contradicting its insistence to Abrams that it would never attack a hospital, NetWalker hit one medical facility after another. The group “specifically targeted the health-care sector during the COVID-19 pandemic, taking advantage of the global crisis to extort victims,” according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

“Hi! Your files are encrypted,” its ransom note read. “Our encryption algorithms are very strong and your files are very well protected, you can’t hope to recover them without our help. The only way to get your files back is to cooperate with us and get the decrypter program … For us this is just business.”

In June 2020, NetWalker attacked a Maryland nursing-home chain and breached the private records of almost 48,000 seniors, which included Social Security numbers, birth dates, diagnoses, and treatments. When the company didn’t pay the ransom, the gang dumped a batch of data online.

That same month, NetWalker stole data from and shut down several servers for the epidemiology-and-biostatistics department at the University of California, San Francisco, demanding a $3 million ransom.

“We’ve poured almost all funds into COVID-19 research to help cure this disease,” the university’s negotiator pleaded. “That on top of all the cuts due to classes being canceled has put a serious strain on the whole school.”

NetWalker’s representative was skeptical: “You need to understand, for you as a big university, our price is shit. You can collect that money in a couple of hours. You need to take us seriously. If we’ll release on our blog student records/data, I’m 100% sure you will lose more than our price.”

NetWalker scorned counteroffers of $390,000 and $780,000: “Keep that $780k to buy Mc Donalds for all employers. Is very small amount for us … Is like, I worked for nothing.” After six days of haggling, they compromised on $1.14 million and UCSF received the decryption tool.

The Ransomware Hunting Team was unable to crack NetWalker. “It’s one of the most sophisticated ransomwares now. Very secure,” Gillespie, the team member from Bloomington, said.

But in a rare moment of success for that time, the FBI disrupted NetWalker’s operations and took down its most profitable affiliate. Although the group’s developers were based in Russia, the alleged affiliate, Sebastien Vachon-Desjardins, was a Canadian citizen living in Quebec. An IT technician for the Canadian government’s purchasing agency and a convicted drug trafficker, Vachon-Desjardins apparently hooked up with NetWalker by answering an ad that a gang member named Bugatti had posted on a cybercriminal forum in March 2020. The ad explained how to become a NetWalker affiliate and asked applicants about their areas of expertise and experience working with other ransomware strains.

“We are interested in people who work for quality,” Bugatti wrote. “We give preference to those who know how to work with large networks.”

Sebastien Vachon-Desjardins and his co-conspirators committed dozens of ransomware attacks in 2020, raking in at least $27.7 million, according to court documents in the U.S. and Canada. Vachon-Desjardins kept 75 percent of the profits with the rest going to NetWalker.

During a conversation in November 2020 with Bugatti, Vachon-Desjardins referred to an attack on a public utility as his “latest big hit.” “I hit them hard bro,” he wrote. “Very locked.” He added that he would visit Russia soon, but the trip didn’t materialize. In December, Vachon-Desjardins was indicted on computer-fraud charges in federal court in Florida, where one of his first victims, a telecommunications company, was headquartered. When Canadian authorities, which were also investigating him, searched his cryptocurrency wallets in January 2021, they found $40 million in bitcoin — the largest cryptocurrency seizure in Canadian history. He was arrested and extradited to the U.S.

By mostly avoiding direct attacks on patient care, the ransomware gangs that agreed to Abrams’s truce might have forgone some revenue. They compensated for this by attacking another vital and vulnerable sector: schools.

Before the pandemic, schools infected with ransomware could still hold in-person classes. But once they went online to avoid spreading COVID, ransomware could shut them down, increasing the pressure to pay. School closures and cancellations associated with ransomware tripled from 2019 to 2020.

Maze was one of the truce participants that targeted schools. The group penetrated and posted data from the nation’s fifth- and 11th-biggest districts: Clark County, Nevada, and Fairfax County, Virginia.

DoppelPaymer disrupted schools from Mississippi to Montana. After the school district in rural Chatham County, North Carolina, rejected its $2.4 million ransom demand, the gang posted stolen data online that included medical evaluations of neglected children.

Also among the leaders in school attacks was a major gang that had ignored Abrams’s proposal: Ryuk. On the evening of Tuesday, November 24, 2020, a Ryuk attack that officials described as catastrophic took down websites, networks, and files of the nation’s 24th-largest district, Baltimore County, whose 115,000 students were attending classes online.

The county schools were susceptible. An audit by the state legislature completed in February 2020 found that servers weren’t properly isolated and, “if compromised, could expose the internal network to attack from external sources.”

The ransomware attack closed schools for three days and reverberated for months. The school system couldn’t generate student report cards, and it struggled to supply transcripts for seniors applying to college and graduates seeking jobs. With payroll records inaccessible, the district had to determine staff pay based on canceled checks and obtain permission from the Internal Revenue Service to extend the deadline for filing and generating W-2 tax forms. Teachers couldn’t make deposits in or withdrawals from their retirement accounts.

The attack disabled laptops belonging to about 20 percent of the teachers — those who were online and connected to the schools’ network that night. One was Tina Wilson, a 17-year veteran of the district and a language-arts teacher at Catonsville Middle School. When she could finally log on a week later, her files were frozen and they had a new extension: .ryk.

She had lost her lesson plans. So on the first day back, she read The Maze Runner, a young-adult science-fiction novel, to her students. They were scrambling too. She had assigned them to write research papers on how to prepare for natural disasters, but they couldn’t get into the database she had suggested.

“What bothered me is that the district had loopholes in the system that they had never fixed,” Wilson said.

The suburban district tried to negotiate with the hackers. “They had to try to find a way to bring classes back as soon as possible,” said Joshua Muhumuza, then a Dundalk High School senior and the student representative on the school board. But the county government, which funds the district, warned of “legal, financial and reputational consequences to an independent decision by BCPS to pay the ransom. Those consequences will be wide-ranging and long-lasting.” School officials apparently heeded the admonishments. Although the district hasn’t discussed the matter publicly, one insider said that it didn’t pay. Recovering from the attack cost Baltimore County nearly $8 million.

For Ryuk, attacking schools was a sideshow. After crippling the DCH Regional Medical Center in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and other hospitals in 2019, it doubled down on health-care attacks in October 2020, sowing anxiety and confusion among patients and providers across the country. The timing suggests that Ryuk was avenging one of the biggest and most damaging actions taken against ransomware.

Since 2018, Microsoft’s Digital Crimes Unit — more than 40 full-time investigators, analysts, data scientists, engineers, and attorneys — had been investigating TrickBot, the Russian malware Ryuk used to hack into victims’ computers. Microsoft investigators analyzed 61,000 samples of the malware as well as the infrastructure underpinning the network of infected computers. They discovered how TrickBot’s command-and-control servers communicated with these computers, and they identified the IP addresses of the servers.

Microsoft then parlayed this evidence into an innovative legal strategy. Contending that TrickBot’s malicious use of Microsoft’s code was violating copyright, the company obtained a federal court order to dismantle the botnet’s operations. In October 2020, with the help of technology companies and telecommunications providers around the world, Microsoft disabled IP addresses associated with TrickBot, rendered the content stored on its command-and-control servers inaccessible, and suspended services to the botnet’s operators. Within a week, Microsoft succeeded in taking down 120 of the 128 servers it had identified as TrickBot infrastructure.

Before going to court, Microsoft had shared its plans with law-enforcement contacts. Word reached U.S. Cyber Command, which oversees Department of Defense cyberoperations. Reflecting the U.S. military’s new, more aggressive cyberstrategy, Cyber Command mounted its own offensive against TrickBot. Without identifying itself, it penetrated the botnet, instructing infected systems to disconnect and flooding TrickBot’s database with false information about new victims.

TrickBot’s hackers were impressed by the then-unknown assailant’s expertise. “The one who made this thing did it very well,” a coder told the syndicate’s boss. “He knew how bot worked, possibly saw the source code, and reverse engineered it … This appears to be sabotage.” These triumphs, however, proved temporary. Ryuk paused only a week to restructure operations before launching an assault on hospitals. “I was super-surprised that the actors behind TrickBot decided to use the limited infrastructure they had left to try to attack the most vulnerable systems out there during a pandemic,” said Amy Hogan-Burney, general manager of Microsoft’s Digital Crimes Unit.

One early victim in this onslaught was Dickinson County Healthcare System in Michigan and Wisconsin, which Ryuk hit on October 17, 2020. “Salute DCHS,” the ransom note read. “Read this message CLOSELY and call someone from technical division. Your information is completely ENCODED.” Giving an address at ProtonMail, Ryuk advised, “Get in touch with us.” Its electronic systems were down for a week, and its hospitals and clinics had to rely on paper records.

On October 26, a cybersecurity researcher named Alex Holden learned that Ryuk was about to strike more than 400 health-care facilities in the U.S., including hospitals and clinics. “They are fucked in USA,” one Ryuk hacker wrote to another. “They will panic.”

Holden immediately shared the information with the Secret Service, including indications that the malware had penetrated some hospital networks. Based in part on his tip, the federal government warned of “an increased and imminent cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and health-care providers.”

Along with federal officials, Microsoft, and major cybersecurity firms, Holden quickly alerted as many of the targeted hospitals as possible to fortify their defenses. As a result, he said, at least 200 locations averted attacks and the impact wasn’t as widespread as feared. But not all of the facilities in danger could be identified in time.

In the intercepted communications from Ryuk, Holden saw references to one particular target with domain names that included the prefix SL. But he couldn’t connect the initials to any particular facility. Then, at eight minutes after noon on October 26, an employee at Sky Lakes Medical Center in Klamath Falls, a city in southern Oregon, received an email that purported to contain “Annual Bonus Report #783.” The employee, who had worked at the community hospital in support services for less than a year, wondered if the message was related to a recent meeting she’d had with human resources. She clicked on a link and her computer froze, which annoyed her, but she didn’t report it.

Not until more than 13 hours later, in the early morning of October 27, did the hospital’s IT staff learn, in a phone call from clinicians, that the system was slow. It took two more hours and a failed attempt to reboot before they realized Sky Lakes was under attack. Ryuk’s ransomware had spread throughout the network, compromising every Windows-based machine.

At a time when COVID was surging after a summer lull, Sky Lakes doctors and nurses lost access to electronic records and images for more than three weeks, curtailing treatments, reducing revenues, and increasing chances for medical errors. “This was a huge blow,” said John Gaede, director of information systems at Sky Lakes. At the FBI’s urging, the hospital decided not to pay the ransom.

Sometimes patients who needed emergency care couldn’t remember what medications they were taking; instead of checking an electronic database, the hospital pharmacist had to call the other pharmacies in Klamath Falls and ask what their records showed. Doctors’ ability to diagnose illnesses was also hampered. Ordinarily, oncologists detect breast cancer by comparing a patient’s new mammogram to older ones, but those images weren’t available.

Sky Lakes sent some cancer patients to Providence Medford Medical Center in Medford, Oregon, a 70-mile drive over the Cascade Mountains. Among them was Ron Jackson, a retired carpenter and heavy-equipment operator for the Oregon Institute of Technology, a public university in Klamath Falls. In September 2020, Jackson had a seizure and couldn’t remember common words like squirrel. He was diagnosed with glioblastoma, the aggressive brain cancer that had killed senators Ted Kennedy and John McCain. The tumor was removed a month later, on October 7. Jackson was about to begin a 30-day regimen of radiation and oral chemotherapy when the Ryuk attack disabled the hospital.

Jackson’s doctor called and gave him a choice: He could wait for radiation services to reopen, and there was no telling how long that would take, or he could go to Medford. Since the doctors had told him that he needed treatment as soon as possible, he and his wife, Sherry, opted for Medford. Although the hospital there was willing to provide housing, Jackson demurred; he wanted to stay in Klamath Falls to help his 97-year-old mother with groceries and doctors’ appointments. He and Sherry also declined offers from friends and family to chauffeur them. “We’re not used to asking for help,” Sherry said. “We’re used to giving help.”

Jackson had always done the driving, but the surgery had affected his vision. So for 17 days, until he could resume treatments at Sky Lakes, Sherry drove their Jeep Grand Cherokee over the mountains to Medford, sometimes through ice and snow. “It was a white-knuckle drive,” Sherry said. “Ron was holding on tight.”

Because roadside restaurants were closed for the pandemic, the Jacksons occasionally had to relieve themselves in the woods. “Sometimes those water pills didn’t make it to Medford,” said Jackson, who was taking diuretics to offset the fluid retention that is often a side effect of chemotherapy.

Still, he and Sherry agreed with the hospital’s decision not to pay the ransom. “We feel the hospital could be hit again by the same group for more money and again stop Ron’s treatments,” she said. “How could you trust that they would not continue to come back over and over again?”

Jackson battled valiantly against the cancer and underwent a second brain surgery in June 2022. “Ron is the love of my life and has been for 56 years,” Sherry wrote in a July email. “He still winks at me and today it brought me to tears.”

For 23 days, Sky Lakes went back in time, reverting to the long-abandoned practice of keeping medical records on paper and by hand. Once it replaced the 2,500 infected computers, all the paper records that had accumulated in the weeks while its systems were down still had to be entered into the system manually — a slow, laborious process. The hospital had prudently invested in a new backup system six months before the attack, and it recovered almost all of its files. Out of 1.5 million mammogram films, just 764 were missing.

Although Sky Lakes is insured, its policy “won’t even come close to covering all of our losses,” which were between $3 million and $10 million, a hospital administrator said. Plus its insurance premiums rose as a result of the claim.

Retracing what had gone wrong, Gaede and two other managers interviewed the employee who had accidentally exposed Sky Lakes to Ryuk’s ransomware. They felt that, since a vigilant workforce is a primary defense against cyberattacks, it was crucial to understand why she hadn’t obeyed warnings to be on the lookout for suspicious emails.

They told her she wouldn’t be punished and they just wanted to learn from her experience. But as they gently questioned her in the second-floor meeting room, the significance of her mistake dawned on her and she went pale. Not long afterward, she quit her job.

Today, the hospital has reconfigured its defenses and sends regular cybersecurity-awareness messages to all staff. While it hasn’t been struck by ransomware again, Sky Lakes is seeing an increase in hacking attempts from overseas, Gaede said. Hospitals that haven’t experienced a ransomware attack, he added, “have no idea how impactful this is and what it takes to actually recover.”

Since the attack on Sky Lakes, ransomware groups such as Hive and Maui, which is backed by the North Korean government, have locked records at dozens of U.S. health-care organizations. Overall, attacks are as prevalent and damaging as ever, and the Ransomware Hunting Team has its hands full. But Abrams’s initiative started a trend. Whether they agreed to his proposal or not, many gangs have adopted what amounts to a cease-fire on hospitals and shifted their sights to lower-profile targets such as colleges and midsize businesses. Especially with the U.S. government stepping up its efforts to fight ransomware, they don’t want to attract undue attention.

At the peak of the pandemic, Abrams was in communication with ransomware attackers around the world. Some were defiant, but others confided their worries that they or their families would fall ill. “They would sign off saying, ‘Stay safe, stay healthy,’ ” Abrams said. “They realized, in many cases, that it’s not as important to make money by targeting hospitals because they’re under extreme stress. I think it carried over as time has gone on.”

Adapted from The Ransomware Hunting Team: A Band of Misfits’ Improbable Crusade to Save the World From Cybercrime, by Renee Dudley and Daniel Golden. To be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux on October 25.