This Old Store: Rural groceries were once centers of small-town life

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

They once dotted the countryside and villages of northern Door County: the little grocery stores that met so many needs. In the days when many families had no automobile — or women did not drive — homemakers depended on a store being within walking distance. They needed a shop where they could send a child for an item that was needed immediately, such as an ingredient for a cake that was already in process or extra pork chops when unexpected company arrived.

Many of the little stores started as butcher shops, so they generally had some method of refrigeration — even if it was just ice cut from the lake or bay and stored in sawdust — when few homes did. Store owners who did not butcher their own meat had it delivered regularly, and fresh meat was especially valued when the home-canned or salted supply ran out. Flour and sugar were sold by the pound out of barrels, and vinegar also came in a barrel with a pump for dispensing the desired amount.

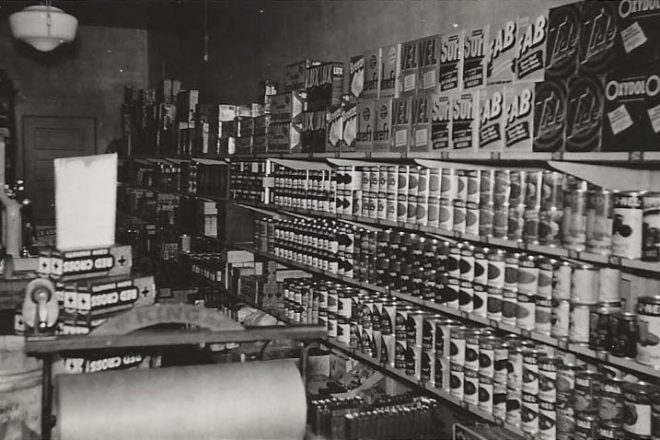

Stores’ shelves contained rows and rows of canned goods and staples such as crackers and cereal, and there was often a box of hard candy on the counter for children and cheese samples for adults. There were no shopping carts or baskets. Customers either handed their list to the grocer or recited the needed items, which were retrieved and boxed up. There were no paper bags and certainly no plastic ones.

Many little grocery stores also carried a multitude of nonfood items such as clothing, shoes, housewares, lanterns, chicken feed and — if they were near a harbor or campground — the many supplies that boaters and campers needed.

The stores served as community centers as well: repositories of news and places to find camaraderie. Most were heated by pot-belly stoves, which made them a convenient place for men to gather — usually with a spittoon nearby. For many farmers’ wives, the “butter and egg money” they earned each week was their only personal income, and it provided their chance to visit with other women while their orders were being filled. It may have been their only nonfamily social contact in weeks.

Travel from Northern Door to Sturgeon Bay during the early 1900s was not an everyday occurrence. Unless it was a necessity — acquiring a part for broken-down machinery at harvest time, for instance — shopping near home was much easier. Many of the little stores had a gas pump out front, which was a convenience for locals and tourists alike, but the pumps worked by gravity and weren’t dependable in hot weather.

People felt a connection to “their” store. Even if a small town had two or three, families usually shopped exclusively at one of them. Many of the grocers were available in emergencies, day or night, because it was common for their families to live behind or over the shops.

Those little old stores were blessings to their communities for so long. Often they had one of the first telephones in town, and it was not unusual to find a shelf or two of books in back — a sort of early lending library. And in the days when a family’s income depended mainly on a successful harvest, most grocers understood the need to buy food “on credit.”

So what happened to these old stores? They didn’t all disappear at once. Many were gone by the middle of the 20th century, but some hung on until the early 1990s, and a few even remain open today. In most cases, there were no longer family members who were willing to put in the long hours. Ten to 13 hours a day, Monday through Saturday, was not unusual, and some village stores opened on Sunday mornings for farm families whose only trip to town was for church services.

As roads improved and cars became more common, the lure of lower prices and a greater variety of merchandise in Sturgeon Bay stores drew people out of their neighborhoods. What was lost? The convenience of a store just down the road and a valuable part of the community.

What replaced those little stores? The Piggly Wiggly in Sister Bay, built in 1983; and Main Street Market in Egg Harbor, built in 1987. Gas stations such as Baileys 57 in Baileys Harbor and other BP stations near Carlsville and Fish Creek that have increased their grocery offerings far beyond the basic bread and milk. The morning coffee klatch at Baileys 57 is, in some ways, a politically correct version of the old Reinhard-Nippert Store’s “BS group” — a nickname so commonly used that there was even a sign directing travelers to the Ephraim Airport and the BS Store.

And then there are the historical little groceries that never left: the Fish Creek Market, established in 1895; the Pioneer Store in Ellison Bay, established in 1900; and Bley’s Grocery Store in Jacksonport, established in 1956.

To kick off the series that looks at these stores, the people who worked their counters, and the role they played in their corner of Door County, we take a look at Washichek’s, the old story that stood for nearly a century at Peninsula Center. More stories will follow each week in the Peninsula Pulse.

Washichek’s

Joseph Washichek had already been a cheesemaker for 13 years when he married Rose Nottling in 1907. Two years later, they purchased land at the southwest corner of the intersection of Highways A and E — known to locals as Peninsula Center — with a loan of $800 from the Merchants Exchange Bank in Sturgeon Bay.

After clearing the land, they built a small cheese factory attached to a two-story building that housed a general store and the family’s kitchen and living room on the ground floor and their bedrooms upstairs. The oldest of the couple’s five daughters died in infancy. Their daughters Julia and Nettie married and moved to Sturgeon Bay, but daughter Agnes, who married Cletus Zettel, and daughter Ann stayed to help their parents run the store.

The fact that Joseph Washichek was a genial storekeeper who spoke Polish and German, as well as the English and Czech he’d learned from his parents, helped the store become a community center. It was open 8 am to 9 pm six days a week.

At some point, the cheese factory was converted into a storeroom for bags of chicken feed, salt blocks and other necessities for farm animals. Up a few steps, shoppers could find clothes, shoes, pots and pans, lanterns and food.

Washichek died in 1946. Rose was killed three years later, when she was hit by a truck on a dark, rainy afternoon in November as she was crossing Highway E to return a “setting hen” — she called it a “cluck” — to her neighbor, Hattie Anschutz.

Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten, the granddaughter of Agnes and Cletus, grew up just south of the store, where her father, John, had a cherry orchard and sold, repaired and rented snowmobiles. Her parents helped Ann run the store after Agnes died in 1988. Jen remembers feasting on blueberries each summer when her grandfather delivered a truckload of them — and Michigan peaches — to the store.

John Zettel enjoys a peach off the back of the delivery truck at Washichek’s, circa 1970. Photo courtesy of Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten.

Washichek’s in 1961. They still had the big windows out front by the door. Photo courtesy of Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten.

Julia’s son, Greg Smith, visited the store often as a child. He remembers big wheels of cheese and the wood-burning cook stove in the kitchen, even after the building had electricity. There were always cats sleeping under the stove, and his aunts had a succession of dogs — usually collies and all named Daisy May.

Nettie Washichek married Clem Habermann, the agriculture teacher at Sevastopol High School.

Their daughter, Mary Penny, remembers that her family would hurry to her grandparents’ store when her father got home every Friday so her mother could help her sisters. Friday night was usually the busiest time of the week, when most people went to shop. Groceries were packed in boxes, not bags, and farm families bought a lot — especially during harvest seasons — because they were feeding a lot of people. The children made friends with all the food salespeople, who also made a habit of visiting the store on Friday evenings.

Mary and the other grandchildren loved to run around the store, but when it was busy, they received a couple of pieces of candy from the big box at one end of the counter and were chased down to the family quarters behind the warehouse. The bedrooms above the store were out of bounds for the grandchildren, except at Christmas time, when they were shooed upstairs to play with a stuffed bunny toy. When they heard Santa’s bells, it was their signal to rush down to find a decorated tree and presents. (Because the stairs were steep, the safest way to descend in a hurry was to sit on their bottoms and bump down one step at a time.)

Like Greg, Mary remembers the cats, but she says they were “working cats,” responsible for keeping mice out of the storeroom, and they did not like the children.

On Nov. 7 and 8, 1969, Washichek’s celebrated its 60th anniversary with free ice cream cones, lunch served on both days, and prizes. Mrs. Wilbur Haack of Baileys Harbor won an electric corn popper for having the closest guess (4,431) about the number of beans in a jar (4,472). Items in the store’s Door Reminder ad that week included girls’ shoes for $2.99 (24 pairs, three kinds, not all sizes); popsicles, two for a nickel; pullet eggs, two dozen for 59 cents; and large Chef Boyardee frozen sausage pizzas for 57 cents.

The family tried to keep the store going for a while after Ann’s death in 1991, but the building was sold in 1998 to Bill and Denise Hanusa, who opened the railroad-themed restaurant PC Junction. The little electric trains in the restaurant deliver food to customers in the old cheese factory, while those who can’t get seating on that level watch from upstairs, where the general store was once located.

The Washicheks’ great-granddaughter Jen Zettel-Vandenhouten is delighted with the new life the Hanusas have given the corner where Joe and Rose Washichek built their cheese factory and store 110 years ago. And the black walnut trees Clem Habermann planted behind the store three generations ago are still there, too.