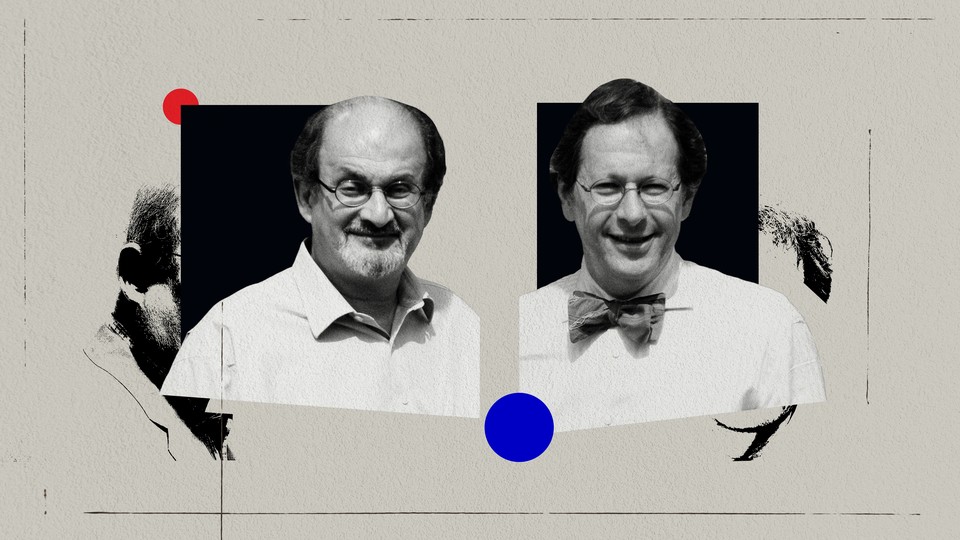

The man who was about to interview Salman Rushdie at the Chautauqua Institution last Friday when a would-be murderer ran onstage with a knife is a 73-year-old former telemarketing entrepreneur from Pittsburgh named Henry Reese. He wears bow ties and speaks with a low-key, husky voice and shuns attention. But Reese and his wife, Diane Samuels, are two of the more remarkable ordinary people in America. They’ve transformed a blighted Pittsburgh street into a haven for persecuted writers and artists from around the world. It’s called City of Asylum, and it’s a physical manifestation of the universal value of free expression. This achievement has something to do with what happened on Friday, two and a half hours north of Reese’s home turf.

The Chautauqua Institution is an idyllic lakeside community, with an entry gate and streets lined by picturesque Victorians, where paying visitors—a lot of them retirees from the Midwest, more middle class than coastal culture seekers—stay for a summer week or so, attending performances and lectures in art, music, literature, ideas, and religion. The institution was founded in 1874 on a tolerant and self-improving strain of American Protestantism that thrived then and is now scarce. I spoke from that stage six weeks ago, and Chautauqua seemed a world apart, rarefied, a little dreamlike and fragile. Of course, there was almost no security—violence in this setting was unimaginable.

Hadi Matar, the man accused of wielding the knife (and who has pleaded not guilty to all charges), may have believed he was enforcing the eternal laws of an ancient book. In fact he came from the contemporary world outside Chautauqua’s gates—a place of irrational hatreds and online threats, where ideas are not so much aired and debated as smothered by self-censorship, stifled by mob pressure, silenced by government decree, or put to death by the gun and the knife.

Reese and I spoke two days after the attack. What, I wanted to know, was he doing onstage with Salman Rushdie? Their paths first crossed in 1997, when Reese and Samuels—he a businessman and she an artist—happened to attend a lecture in Pittsburgh by Rushdie, who’d been invited by his friend Christopher Hitchens, then on the faculty of the University of Pittsburgh. The talk was part of Rushdie’s gradual reemergence into public life following the 1989 death sentence issued by Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. After the fatwa, still under imminent threat, Rushdie had helped found an organization called the International Parliament of Writers to provide solidarity and protection for writers in danger around the world, especially those in Algeria. The organization inspired cities in Europe to provide asylum for persecuted writers. When Rushdie mentioned these cities of asylum in his Pittsburgh talk, Reese and Samuels were struck by the idea of starting one in their hometown—a local, grassroots project.

In 2004 they founded City of Asylum on Pittsburgh’s north side, on a derelict street near a nuisance bar and a porn theater. They bought up adjacent rowhouses, five in all, and began to offer safety, shelter, and support to persecuted writers and artists from Ethiopia, Syria, Venezuela, Vietnam, El Salvador, Cuba, and Algeria. One by one, the tenants on Sampsonia Way brought the shabby block to full-color life, covering the facades with Chinese calligraphy, Burmese murals, Bengali prose, jazz art, and a mosaic based on a passage by the Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka, making the street itself a kind of library. Later Reese and Samuels added a garden and a bookstore. City of Asylum provided not a temporary refuge but a lasting community. (I spoke there in 2009 and sit on the advisory board.)

“The openness of writing is, in fact, social justice,” Reese told me. “The values of openness and protection are what enable a society to build justice. That is a dialogue, nonuniform, always in negotiation, and that’s really what Rushdie and this whole idea of cities of asylum evolved to.” In 2005 Reese invited Rushdie to address a fundraiser in Pittsburgh, and afterward the novelist and the entrepreneur stayed in touch. Last week they met again in Chautauqua and planned their public conversation the night before over dinner. Rushdie wanted to talk about writers in America from other countries and cultures who were “actually redefining what it meant to write American literature,” Reese told me. The larger theme was to be the origin and purpose of cities of asylum—what freedom of expression means, beyond just “abstract language.” Rereading Rushdie’s work, Reese had noticed the recurring imagery of flight and the weight of gravity: “I was really struck by phrases related to being grounded or not grounded, and what that really meant for someone who was migratory himself.” The epigraph of The Satanic Verses, the novel that inspired the fatwa, comes from Daniel Defoe’s The Political History of the Devil and describes Satan’s “vagabond, wandering, unsettled condition … for though he has, in consequence of his angelic nature, a kind of empire in the liquid waste or air, yet this is certainly part of his punishment, that he is … without any fixed abode, place, or space allowed him to rest the sole of his foot upon.” The whole point of cities of asylum is to give the free spirit of art a solid and safe place to land.

The attacker struck before Reese or Rushdie had said a word.

Reese didn’t want to discuss the attack with me; he preferred to talk about the values that had brought him and Rushdie together in Pittsburgh and then Chautauqua. But it became clear why Rushdie is alive. Reese is home in Pittsburgh recovering from a fairly superficial knife wound to his eyelid, which he sustained while holding down the legs of the man stabbing the novelist. At that same moment, audience members climbed onto the stage and subdued the attacker while the knife was still delivering savage thrusts. Judging from videos, these rescuers were white-haired men in shorts—the kind of people you normally see at Chautauqua. A retired doctor from Pittsburgh who is a supporter of City of Asylum attended to Rushdie onstage. Running toward the mayhem took courage.

All kinds of people show bravery in a crisis, and perhaps Rushdie would have been saved anywhere. But he was saved last Friday by members of two communities with similar values—one devoted to the open exchange of ideas, the other to freedom from persecution. “This is a very bold attack against the core values of freedom and ways of resolving differences short of violence, with art, literature, journalism,” Reese said. He experienced the assault as an intense embodiment of the kind of persecution that brings writers to City of Asylum. “It’s given a very visceral, momentary connection to me personally, and certainly to Salman, it’s probably never gone away in the back of his mind—but now it’s caught permanently, in a physical way.”

Freedom of expression—“the whole thing, the whole ball game,” Rushdie once called it—is a universal value that has to be enshrined in law to have any force. But it can’t survive as an abstraction. It depends on public opinion. “If large numbers of people are interested in freedom of speech, there will be freedom of speech, even if the law forbids it,” Orwell wrote; “if public opinion is sluggish, inconvenient minorities will be persecuted, even if laws exist to protect them.” Free speech needs some ground to stand on. It needs a community with enough tolerance and trust for people to refrain from killing one another over ideas. It needs a people willing to defend the right—the life—of someone who says things that they don’t want to hear.