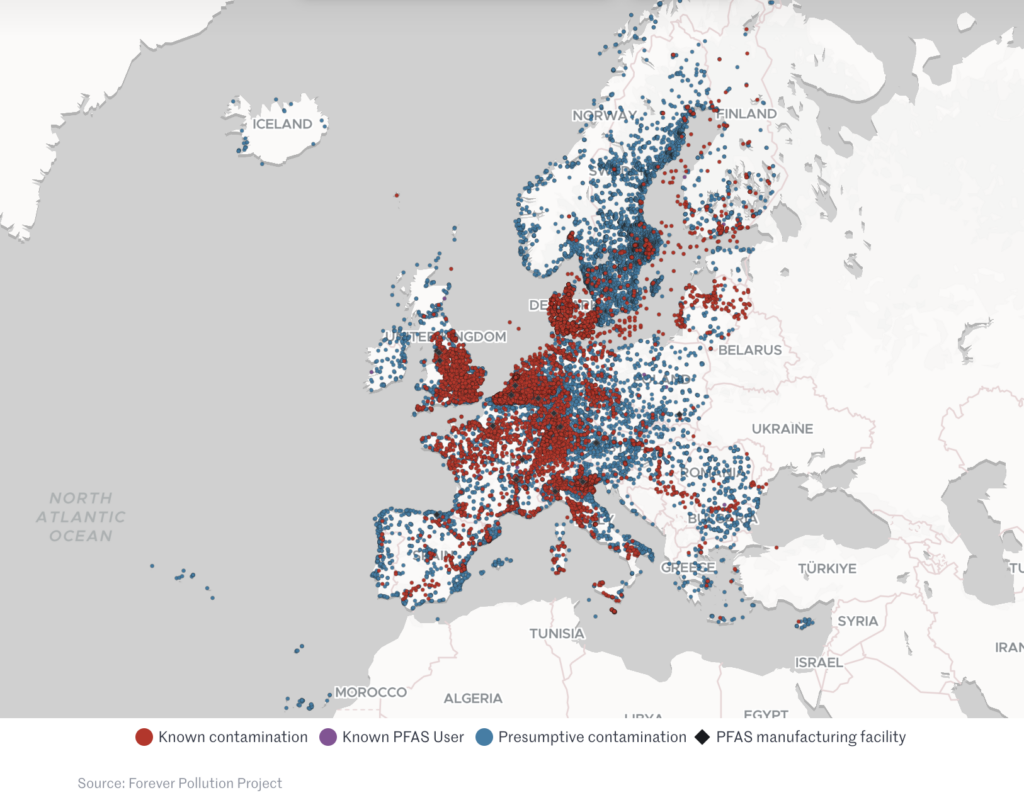

In early 2023, the Forever Pollution Project showed that nearly 23,000 sites all over Europe are contaminated by the “forever chemicals” PFAS. This unique collaborative cross-border and cross-field investigation by 16 European newsrooms revealed an additional 21,500 presumptive contamination sites due to current or past industrial activity. PFAS contamination spreads all over Europe.

Read more

In early February 2023, the European Chemicals Agency ECHA published a ban proposal on all PFAS – or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. In an unprecedented experiment of “expert-reviewed journalism” involving twenty-nine journalists and seven scientific advisers, the Forever Pollution Project revealed that there is way more contamination all over Europe than has been publicly known. The journalists gathered 100 datasets and filed dozens of FOI requests to build a first-of-its-kind public interest tool in the form of a free, online, interactive map of PFAS contamination in Europe. The scientific methodology behind this data collection is borrowed from the PFAS Project Lab and the PFAS Sites and Community Resources Map in the U.S.

“It is a necessary and also scary result that you have achieved here,” said Phil Brown (Northeastern University, Boston), who coordinated the work behind the American map. “Something similar has been missing for Europe,” said Martin Scheringer, an expert in environmental chemistry at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (Zürich, Switzerland). “Your contribution is therefore extremely important and valuable.”

The project shows that there are 20 manufacturing facilities and more than 2 100 sites in Europe that can be considered PFAS hotspots – places where contamination reaches levels considered to be hazardous to the health of exposed people. The problem: It is extremely expensive to get rid of these chemicals, once they have found their way into the environment. The cost of remediation will likely reach the tens of billions of Euros. In several places, the authorities have already given up and decided to keep the toxic chemicals in the ground, because it’s not possible to clean them up.

PFAS are used in a lot of different industries, from Teflon to Scotchgard to make non-stick, non-stain or waterproof products. They don’t degrade in the environment and are very mobile, so they can be detected in water, air, rain, otters and cod, boiled eggs and human beings. PFAS are linked to cancer and infertility, among a dozen other diseases. It was estimated that PFAS put a burden of between 52 and 84 billion euros on European health systems each year.

PFAS emissions are not regulated in the EU yet, and only a few Member States have adopted limits. All the PFAS experts we interviewed were adamant that the thresholds set by the EU for implementation in 2026 are much too high to protect human health.

The Forever Pollution Project also uncovered an extensive lobbying process to water down the proposed EU-wide PFAS ban. Several dozen FOIA requests in Brussels and other European cities revealed that for months now, more than 100 industry associations, think tanks, law firms and major companies have been working to influence the European Commission and the Member States to weaken the forthcoming PFAS ban.

Over the course of several months of investigation, the Forever Pollution Project dissected more than 1 200 confidential documents from the European Commission and the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) as well as hundreds of open sources. Analysing these documents, the reporters behind The Forever Pollution Project can show how companies from Chemours to 3M or Solvay are trying to exempt their products from the ban.

All 23,000 contamination sites and all 21,500 presumptive contamination sites are available at lemde.fr/PFASmap and in the map and data section of this website.

The Forever Pollution Project was initially developed by Le Monde (France), NDR, WDR and Süddeutsche Zeitung (Germany), RADAR Magazine and Le Scienze (Italy), The Investigative Desk and NRC (Netherlands). The project was financially supported by Journalismfund.eu and Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU). The investigation has been further developed and investigated by Knack (Belgium), Denik Referendum (Czechia), YLE (Finland), Reporters United (Greece), Latvian Radio (Latvia), Datadista (Spain), SRF (Switzerland), Watershed Investigations / The Guardian (UK). The crossborder collaborative process was supported by Arena for Journalism in Europe.

Featured Articles

They do not degrade, but accumulate in the environment and in the body. They enter through food, tap water, breathing in house dust. Decades ago humans synthesised a type of unbreakable compound that makes pans non-stick, clothes waterproof, used in electronics and construction. And they are contaminating everything. They are PFAS. A carcinogenic element that above certain levels affects the immune system, the cardiovascular system, the reproductive system and is an endocrine disruptor. This transnational research has succeeded in mapping its presence across Europe. Industry has been delaying the ban for decades. This is the story.

Read morePFAS are used in many different sectors: to make non-stick pans, waterproof jackets, pizza boxes. They do not degrade in the environment and are very mobile, so they can be detected in water, air, rain, otters and cod, boiled eggs and humans. PFAS are linked to cancer and infertility, as well as a dozen other diseases.

Read moreMore than 1.000 contaminated sites and 5 of the 20 European PFAS production facilities have been identified in France. Manufactures in the “chemical valley,” seem to be at the origin of the largest PFAS pollution to date in the country. Le Monde also reveals that Rumilly, the hometown of the worldwide famous brand of non-stick cookware Tefal is highly contaminated.

Read moreSo far, the public has mainly been discussing a few PFAS hotspots. Now, for the first time, Panorama reporters, together with colleagues from WDR and “Süddeutsche Zeitung”, have found more than 1,500 sites polluted with PFAS for Germany, including more than 300 hotspots. And with 18 European partner media, they have located more than 17,000 places with relevant PFAS pollution throughout Europe in the “Forever Pollution Project”, including a good 2,000 hotspots with significant risks to human health.

Read more