For Spokane International Airport (SIA) CEO Larry Krauter, there is no more important real estate in the world than the land around the airport’s tarmacs on the West Plains, which he is doggedly developing into a revenue-generating, economy-growing powerhouse. That work, more than anything else, draws economic activity to Spokane, increasing the capacity of the local skies. And the goal is more air traffic – always more.

Krauter is set up well for this, as he said in a May 2023 interview on Spokane County TV with Al French, the county’s longest-serving commissioner: “What might surprise people,” Krauter said of SIA, “is that it’s 6,400 acres in size. We’ve planned it well in order to have plenty of room to expand well into the future.”

Are there any limits to the airport’s development? “From an airfield perspective, no,” Krauter told the Spokesman in 2018. “We have enough land to support a parallel runway.” The only constraints — parking and security — would benefit from federal investment and increased capacity. That’s why the expansion of SIA’s Terminal C, then only conceptual but now nearing completion, is the largest expansion in the airport’s history — and one of the tallest feathers in Krauter’s well-decorated cap.

On the ground, things are good at SIA. But what Krauter didn’t mention in any interview was something that, for six years, has also been an object of his focus: the poison lurking beneath the surface.

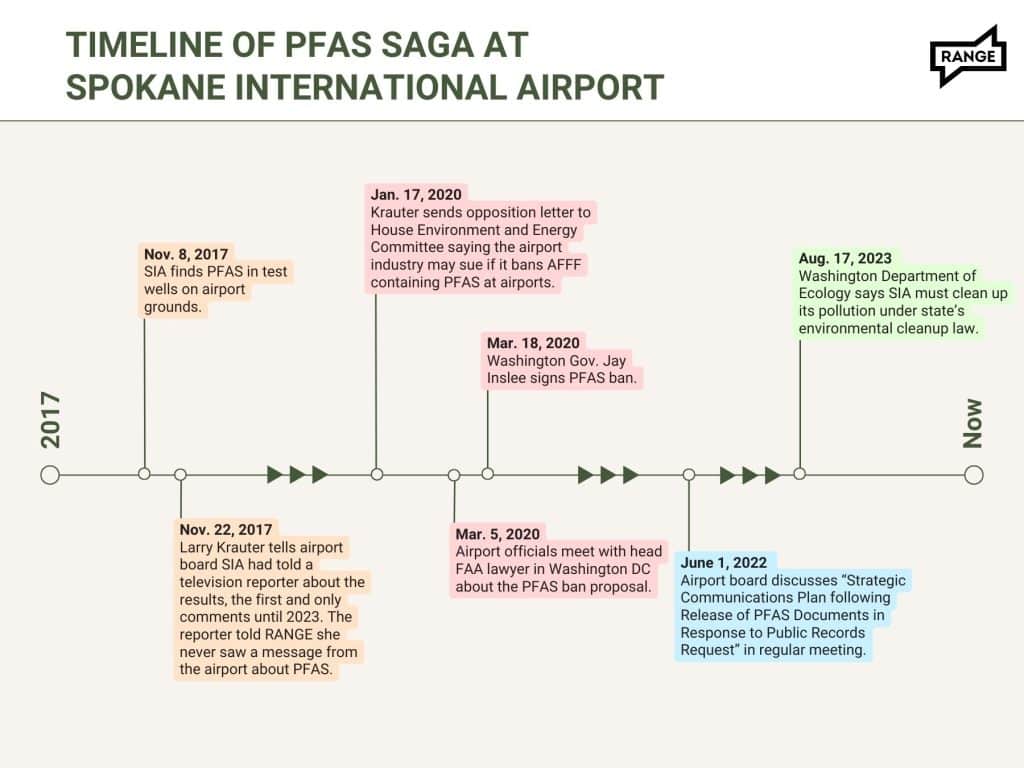

From 2017, when it first tested its well for PFAS, until August 2023, SIA talked publicly only once — in comments that got no traction in the news, and may not have even reached the reporter it sent them to — about the toxic chemical compounds it had put into West Plains groundwater as the result of federally-required firefighting drills using aqueous film forming foam (AFFF).

AFFFs are the best-known weapon for fighting petroleum-based fires, but the foam’s active ingredients were several kinds of so-called “forever chemicals,” known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) which have been linked to cancer, birth defects, liver and kidney problems and exist in many household products.

After a regulatory change by the Washington Department of Ecology (DoE) in 2021 requiring the disclosure of PFAS contamination, Krauter and SIA still didn’t disclose the West Plains contamination — even to Ecology itself. DoE only learned about the airport’s contamination after a private citizen requested the records and sent them to the state agency.

And while Krauter and his colleagues weren’t disclosing the contamination to the public, they also weren’t ignoring forever chemicals. In fact, PFAS was a top priority for airport officials.

They were actively lobbying to keep using them.

Internal emails obtained by RANGE through a public records request show that in 2020, SIA concentrated its efforts on keeping the state of Washington from regulating the chemicals at airports. Airport officials sent letters threatening legal action to the Legislature, which was considering legislation that would ban PFAS in AFFF at airports, and in 2020 even flew to Washington, D.C., in part to meet with the FAA’s top lawyer about that proposed legislation.

Krauter and SIA spokesperson Todd Woodard did not respond to a request for an interview.

Amid drinking water crisis, Fairchild volunteers as tribute

As SIA tried to stop the PFAS ban, people suffered.

West Plains residents, who did not know of SIA’s contamination, had been concerned with severe — sometimes deadly — liver and kidney problems and cancer cases that seemed to be surfacing with alarming frequency. People were dying.

It’s important to note that public health agencies have not identified a cancer cluster on the West Plains, and some data suggest there isn’t one. Kara Kostanich, a spokesperson for the Washington Department of Health, said the agency investigated kidney and pancreatic cancer rates on the West Plains and could not identify a cancer cluster.

“Age-adjusted rates of all cancer types combined and pancreatic cancer were significantly lower in the West Plains study area compared to Spokane County and Washington State as a whole, while age-adjusted rates of kidney cancer were not found to be significantly different within the study area compared to Spokane County and Washington State as a whole,” Kostanich wrote in response to questions from RANGE.

But that doesn’t jive with what activists on the ground in the West Plains have documented in speaking with their neighbors. West Plains Water Coalition (WPWC) founder John Hancock, who spent much of last year trying to produce better data about the contamination, says public health officials have not looked at where people diagnosed with cancer are getting their water — crucial information to determine if there is a cancer cluster.

In the United States, the baseline rate of pancreatic cancer hovers around seven cases per 100,000 people. “In our work together,” Hancock said in an email to RANGE, referencing the WPWC’s organizing, “with fewer than 1,000 people, we have names of at least five neighbors who died of pancreatic cancer, all of whom drank contaminated well water.”

If those numbers are correct, pancreatic cancer is over 70-times more common on the West Plains than the rest of the United States.

Pancreatic cancer kills 90% to 95% of people diagnosed with the disease within five years and is known to be caused by PFAS.

Fairchild Air Force Base (Fairchild) knew it had caused similar contamination from firefighting drills identical to those that had occurred at SIA. In contrast to SIA, Fairchild told the Spokane Regional Health District about the potential health hazard in 2017 and publicized information about the contamination, enabling the city of Airway Heights to buy clean municipal water from Spokane, which it does to this day. Fairchild established its own modest water program, delivering bottled water or installing expensive — but frequently malfunctioning — carbon filters for some private well owners who don’t benefit from the arrangement between Airway Heights and Spokane.

Despite learning of their contamination at approximately the same time, Krauter and officials from SIA quietly allowed Fairchild to bear the public burden of PFAS contamination on its own. The airport was growing and, for now, it had dodged any fallout for its own pollution.

Almost telling on themselves

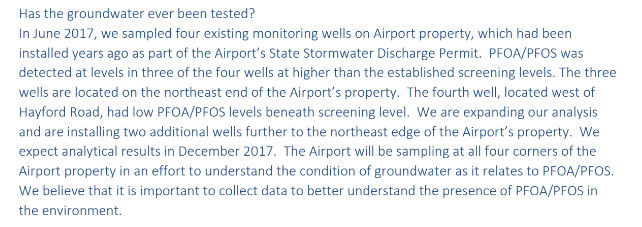

Just months after well samples taken from the SIA campus in mid-2017 showed dangerously high levels of the cancer-causing chemicals, Krauter sent the airport board an email claiming SIA had divulged the test results to KREM 2 News reporter Whitney Ward.

“In June 2017, we sampled four existing monitoring wells on Airport property,” Krauter said the airport wrote to Ward in November of that year. The chemicals, according to Krauter’s email, were “detected at levels in three of the four wells at higher than the established screening levels.”

It’s unclear from Krauter’s email when these comments — which appear to have been copied and pasted into the email to the board, omitting any email chain — had been sent to Ward, who had sent them or how they had been sent. But after RANGE forwarded her the message, Ward and her lead investigative producer searched their email histories. Neither account, Ward said, yielded the message. She said it was possible the remarks went to a lower-level producer who worked on that story at the time and they were lost in the news shuffle. In any case, Ward said she never heard directly from Krauter or Woodard about the test results.

Language that Krauter told the airport board had been sent to KREM 2 reporter Whitney Ward in 2017. Ward told RANGE she never saw the message.

These were the first and only publicly-facing comments made by anyone at the Airport on the PFAS situation until last August.

“I did not personally know about contamination in the groundwater at the airport until the last month or so,” Ward said in an email to RANGE this month. “In fact, when I heard about it last month, I remember saying, ‘What?!?’”

‘No choice’ but to sue

In the mid-2010s, several prominent lawsuits over the toxicity of PFAS — which chemical manufacturers understood through their internal research, but for decades hid from regulators — were prompting bans on some PFAS products, including in Washington, which barred the use of AFFF in firefighting drills.

But the state continued to allow AFFF at three kinds of places: oil refineries, manufacturing plants that make flammable liquids and airports like SIA, where the federal government required AFFF use in firefighting drills.

In December 2019, Rep. Beth Doglio, D-Olympia, sponsored legislation to eliminate those exemptions by requiring airports in the state to stop using AFFF. One month later, Krauter told the House of Representatives that the airport industry could sue it if it passed Doglio’s proposal.

Banning AFFF with PFAS at airports “would set a negative public policy precedent on the part of the State of Washington to improperly and unlawfully insert itself into areas of airport operations that are regulated by federal law,” Krauter wrote in a Jan. 17, 2020, letter addressed to the House Environment and Energy Committee. He said the “traveling public” would be harmed by the inherent conflict between banning AFFF use at airports when the FAA requires it.

“Accordingly, if this legislation is enacted into law then airports would have no choice but to challenge its validity in federal court,” Krauter wrote.

From Krauter’s Jan. 17, 2020 letter to the Washington state House of Representatives Environment and Energy Committee.

Doglio had worked to regulate the chemical industry for decades, first as an activist mother to an infant in the 1990s, when she lobbied the state to regulate toxic chemicals used in many plastics that were appearing in women’s breast milk. Now, as chair of the Washington House Environment and Energy Committee, Doglio told RANGE she was “taken aback” by Krauter’s opposition to a bill that had the support of firefighters, who are one of the main constituencies lobbying to ban AFFF with PFAS because they work so closely with it. (Doglio was not the committee chair when Krauter sent his letter.)

“There was such clear bipartisan support for the move away from PFAS in firefighting foam at airports,” Doglio said. “And I think firefighters in particular were like, ‘This is our livelihood. We are the ones who are on the front lines here.’ To have this kind of opposition just flies in the face of all the research and all the data and everything that we know. … I guess the economic incentives of continuing to use PFAS outweighed the public safety angle.”

After he sent the opposition letter, Krauter immediately forwarded it to the entire airport board, with a note that read, in part, “I think the bottom line is that state legislators need to take a wait and see approach before proposing any laws related to airports regarding this matter.”

‘He’s known and respected’

If Krauter had concerns about the health implications of PFAS, he didn’t express them publicly. Perhaps that’s because focusing on the economic role of the airport has served Krauter well in an industry that prizes large development projects.

He does it partly through a public development authority called S3R3 Solutions. S3R3 “marshals the resources of public and private service providers to recruit new and existing businesses into the West Plains Airport Area and drives economic prosperity through the creation of jobs,” according to its website. Krauter and French — the latter a powerful man in many realms of Inland Northwest politics — are vice chair and chair, respectively, of S3R3.

People higher up the industry ladder have noticed Krauter’s work. In 2017, he was named the Airport Director of the Year by Airport Revenue News, a magazine about the airport business. The city of Spokane’s website ran a story about Krauter’s accolade, quoting the magazine’s publisher, Ramon Lo: “After speaking to many aviation executives about a worthy candidate, the name of Larry Krauter was consistently raised. Larry is highly respected within the aviation world, with his efforts in advocating for the aviation industry in Washington, D.C. Additionally, he has increased air service at GEG [SIA’s location identifier] and expects to soon undertake a redevelopment and expansion of GEG.”

The love kept flowing for Krauter. In 2021, the American Association of Airport Executives (AAAE), the largest advocacy group for Krauter’s profession in the world, named Krauter its chair for a one-year term, a post French bragged was “the top of the ladder” when he interviewed Krauter. This spring, Krauter received another prize: AAAE’s award for distinguished service.

Krauter is famous across the state as a vocal airport booster, having testified often on the need to beef up air travel infrastructure in written and oral comments before the state and federal legislatures.

“He’s an extraordinarily well-respected leader out there,” Bruce Beckett, a lobbyist who has represented airports at the Washington Legislature, told RANGE. “He’s known and respected.”

And Krauter has helped win other legislative disputes for the airport industry, including testifying in the Washington Senate against a ban on the use of leaded gasoline at airports that was passed this year by the Washington House but later killed in the Senate.

Runaway plane

Krauter’s diligence on airport business helps explain a theme in documents RANGE reviewed for this story: He believes Washington state has no place regulating any airport activity that federal law touches.

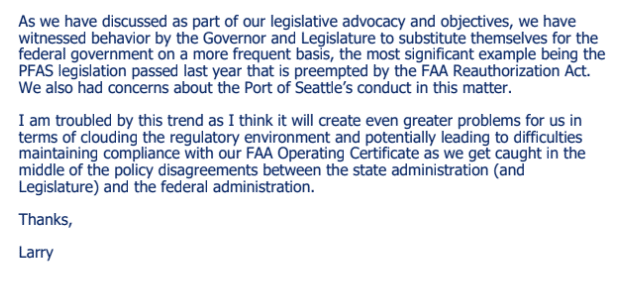

In September 2020, he sent the airport board an email criticizing Gov. Jay Inslee’s proclamation requiring airports in Washington to comply with state public health requirements designed to blunt the COVID-19 pandemic. He likened those public health requirements to Doglio’s proposed PFAS law.

“[W]e have witnessed behavior by the Governor and Legislature to substitute themselves for the federal government on a more frequent basis, the most significant example being the PFAS legislation passed last year that is preempted by the FAA Reauthorization Act,” Krauter wrote. “I am troubled by this trend as I think it will create even greater problems for us in terms of clouding the regulatory environment and potentially leading to difficulties maintaining compliance with our FAA Operating Certificate.”

Krauter’s Sept. 23, 2020, letter to the airport board lambasting Gov. Inslee’s proclamation that the airport must follow COVID guidelines.

His legal logic in opposing the AFFF ban seemed simple enough: Because the federal government required the use of AFFF at federally regulated airports, that requirement would make it impossible to follow any state regulation banning the substance.

This mirrored the sentiment of the rest of the airport industry in Washington, Beckett said. At the time the legislation was in the House, Beckett represented the Port of Moses Lake, which operates and develops the Grant County International Airport. That airport was also required by the FAA to stock AFFF with PFAS in it. Beckett told RANGE the Washington Airport Management Association and airport lobbyists — including Beckett — had the same concerns as Krauter about the bill and worked closely with Doglio to remedy them.

“So what Rep. Doglio did instead of her original bill,” Beckett said, “is to say, ‘Once the FAA has tested and approved an alternative product that does not contain PFAS, then airports have a two-year period in which to, one: get supply, and two: convert your equipment over to use that material. And if it’s not available, there’s a process for a third year.’”

The result: The new PFAS law grew less stringent than an outright and immediate ban. With the workaround to address the conflict between state and federal regulations now in place, the House overwhelmingly passed the bill on Feb. 16, 2020. Spokane Democrats Timm Ormsby and Marcus Riccelli and Spokane County Republican Mike Volz joined 92 other bipartisan lawmakers in voting yes; former Spokane Valley Rep. Matt Shea was one of four legislators to vote no, all Republicans.

After the bill was changed, Beckett said the Port of Moses Lake shifted its stance on the legislation from opposed to “neutral,” but “most airports remained troubled by the cost implications, and the uncertainty of supply of any alternative foam approved by the FAA.”

SIA was expressly unsatisfied even after the bill was amended, according to a second distress signal Woodard sent to FAA Chief Counsel Arjun Garg. SIA spokesperson Woodard wrote to Garg on February 17 — the day after the bill cleared the House — that the airport was now shifting its focus to the Senate, which was preparing to vote on its version of the bill.

“We are very concerned regarding the conflicted nature the proposed legislation would place us in between complying with State and Federal law simultaneously,” Woodard’s email to Garg read.

Two weeks later, Krauter, Woodard and French traveled to Washington, D.C. in part to meet with Garg about the legislation. (They would be in town that week “for congressional meetings and to attend an aviation legislative conference,” Woodard wrote to Garg.)

Garg confirmed a half-hour slice of time on March 5, 2020, when the conference-weary airport officials could visit his office. Krauter, Woodard, Garg and French did not return requests for interviews about that meeting.

On the day of SIA officials’ meeting with Garg, the Washington Senate passed its version of the bill 36-12. Spokane Democrat Andy Billig voted yes. Inslee signed it into law on March 18. Washington airports will eventually have to clean the tanks and firefighting equipment to prepare for new, PFAS-free fire-fighting foam. Beckett said this will be a big task.

“It’s more complicated than just buying new chemical foam,” he said. “The tanks, the trucks, the pumps all need to be intensively cleaned, and it’s extraordinarily expensive to do that. We’re talking $30,000 to $40,000 per tank. … It’s not just changing the dishwasher soap.”

Circling the wagons

For three years after they met with Garg, SIA officials remained quiet about the contamination it had caused, even after the State Department of Ecology (DoE) classified PFAS as hazardous substances, requiring people and organizations to report known spills of the forever chemicals beginning in 2021 — explicitly including past releases like the contamination at SIA and Fairchild.

Fairchild had already disclosed its contamination. Krauter and SIA chose not to disclose its own.

And while Krauter did not return a request for comment, documents reviewed by RANGE show he was concerned about the fallout once the public was made aware.

In 2022, the airport received a public records request for documents showing the well test results.

Krauter was so concerned about the request that he included it as a discussion item on the agendas for two Executive Committee meetings in 2022. The agenda item for the second meeting, on June 1, concerned the airport’s ground game as it braced for the public to react to the documents. It read: “Strategic Communications Plan following Release of PFAS Documents in Response to Public Records Request.”

Whatever came of that plan, the airport has been forced to speak up – at least in writing – since DoE deemed it liable for the cleanup last summer. SIA’s few statements have sought to shift blame, downplayed the severity of the crisis and avoided any in-person engagements with the affected public.

The first communication was a dour August 7, 2023, letter to DoE written by the D.C. lawyer Jeffrey Longsworth, who was representing SIA. Longsworth accused the department of lacking evidence to say the airport was responsible for the contamination, even though the agency was using SIA’s own documents to do so. Longsworth asked DoE to retract its accusation.

“Unnecessary and unfounded negative actions against [the airport] can damage its reputation and community role as well as harm the Airport economically,” he wrote. “Ecology’s ‘investigation’ and arbitrary conclusions and public statements … also have negative impacts that could have been avoided and should be avoided from this point forward.”

DoE reaffirmed its position in a further August 17 letter forcing the airport to begin an environmental cleanup under Washington’s Model Toxics Control Act (MTCA).

Writing in response to questions from the Seattle Times, Woodard emphasized that for at least some of the six years the airport kept quiet about its well tests, it was not legally required to report them.

“[I]n 2017, the Department of Ecology had not yet formulated mandatory reporting requirements for PFAS,” he wrote. “There was no requirement to report in 2017 or 2019.” The Times did not print any statement from Woodard addressing the requirement that bound the airport beginning in 2021.

On December 9, 2023, WPWC founder Hancock, whose group is building datasets and maps that will tell private well owners whether they should worry about PFAS, invited the airport to present at one of the coalition’s public meetings.

Woodard declined, saying the airport needed to be further along in the cleanup process before it could address the public.

“The sources and impacts of PFAS are a challenging and complex issue and part of an evolving national conversation given their reach and scope,” Woodard wrote to Hancock. “We are in the early stages of working with the Department of Ecology, the FAA, and other state and federal agencies and experts to more completely understand the complex issue of PFAS on the West Plains. Therefore, at this time, it is premature to engage in a meeting with the West Plains Water Coalition. In the interim, please visit our website for any updates.”

Hancock read the email aloud at a recent informational meeting with dozens of West Plains residents who are worried their water is poisoned.

The site referred to in Woodard’s email links to a two-page document stating that SIA “will continue investigating PFAS-related issues in a logical, data-driven manner,” and described SIA as spearheading the fight against PFAS contamination.

“Earlier this year, the FAA announced a transition plan to a fluorine-free firefighting foam and recently authorized its use,” according to the document. “As a leader in the industry, the Airport has taken immediate steps to authorize the purchase of the new [PFAS-free] AFFF.”

SIA’s cleanup will likely take between 11 and 12 years, DoE officials told residents at a WPWC meeting in December. Meanwhile, people continue to suffer. At a different WPWC meeting in December, Chuck Danner, who lives about two miles northeast of Fairchild but outside the area its water program serves, was speaking with Dr. Cartherine Karr. Karr is an epidemiologist in the School of Public Health at the University of Washington and had just given a presentation at the meeting about how PFAS affects children. Danner, 71, drinks from a private well and told Karr he had recently had his blood tested for PFAS — the results, which Danner allowed RANGE to read, showed the presence of some kinds of PFAS at more than double the amount to be expected through normal exposure. He has not tested his well, but he can’t imagine where else the PFAS in his blood came from. It is the same kind of PFAS used in AFFF. A well test costs between $350 and $400.

“I figure nothing’s gonna happen through SIA or Fairchild any time soon,” Danner told Karr. “I need to stop drinking PFAS.”

“But it’s really difficult,” Danner added. “For the last several years, I’ve had a filter on my refrigerator,” but a technician told him “that’s a joke.” After shopping around for months he bought a Culligan water dispenser with his own money.

Karr approved of Danner’s purchase: “That would be my best medical advice.”