Strategy, Project Management, and the Marble Machine

Imagine a one-man band. He's got a drum kit on his back that he works using a series of levers and pulleys attached to his feet, a harmonica positioned just in front of his mouth, and a guitar in his hands. It's… a lot. And while he can probably make some amazing music, he's fighting against the public perception of a sideshow novelty; he's no Mozart.

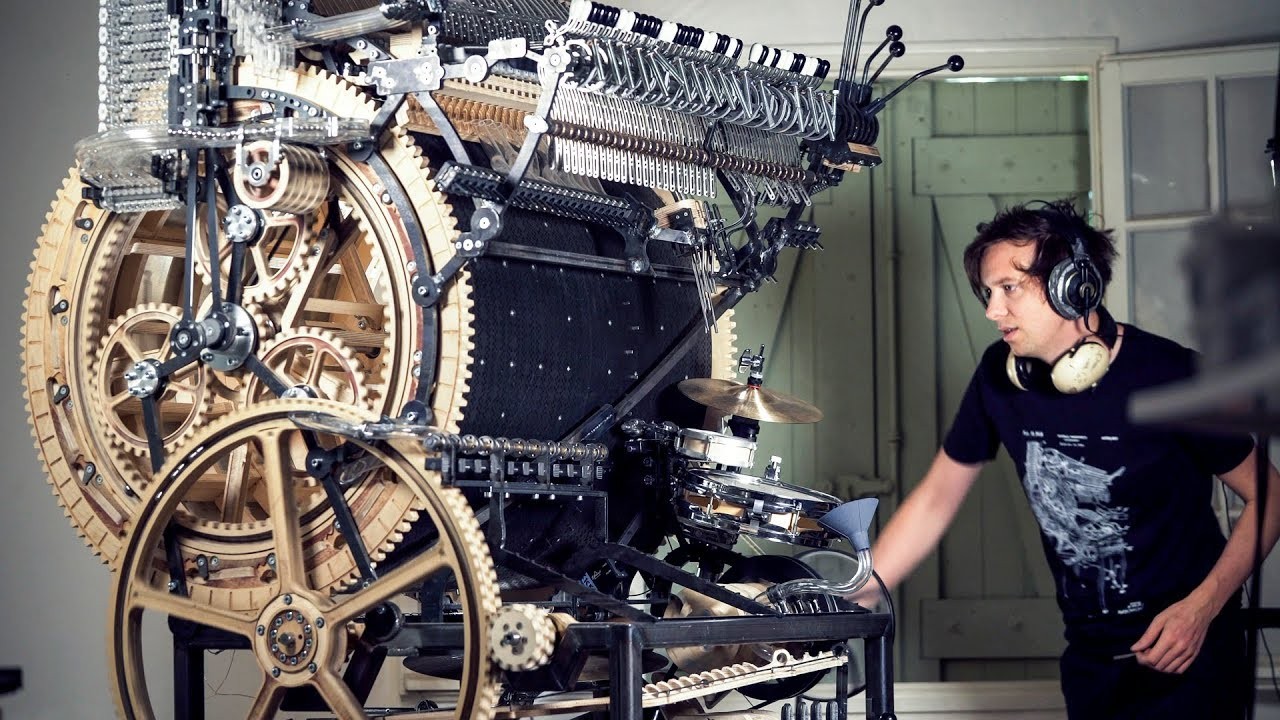

Now imagine taking this concept and morphing it into something truly marvelous. Add over a thousand moving parts. Add a vibraphone. Add the ability to program looping melodies. Now build the whole thing out of plywood. Let's call this new monster the marble machine. It's a series of gears turned via hand crank that drops marbles on the vibraphone, drum kit, and bass guitar individually and in unison, all controlled by a giant, programmable wheel.

Introducing mad scientist and musical genius Martin Molin of the Swedish band, Wintergatan. Martin built the original marble machine as an experiment in musical engineering. With literally thousands of moving parts, it's a wonder that it works at all, and miraculous that it makes music. Check it out here:

The original video of the marble machine, posted in March of 2016, has amassed over 110 million views on YouTube and inspired covers of the original song and copycat machines worldwide.

But Martin didn't stop there. He wanted to go on a world tour with this plywood Frankenstein's monster, but version 1 wouldn't make the cut. It was fragile and changing the programmatic melody of the marble drops was so difficult that doing it during a live show was nigh unto impossible. Due to a series of mechanical problems, the marble machine was retired after recording just one song.

So Martin set off on the design and construction of the Marble Machine X: a larger, more robust metal beast of an engineering marvel that would shore up all of version 1's shortcomings and add features that would allow for more musical expression. That was over two years ago. Martin has documented the design and construction of the Marble Machine X through a series of videos on his YouTube channel: Wintergatan. Following along with his videos has been a consistent highlight of my Wednesday since I first found them several months ago.

As a consultant I couldn't help but see the genius in this undertaking through the lens of strategy, project management, and solutions architecture. I've learned a lot from watching Martin's videos and I'm hoping to share some of that learning here.

Learnings

Begin with the End in Mind

The Marble Machine X's goals are three-fold: new music, new videos, and a world tour. Martin has mentioned at least one of these goals in every construction video of his that I've watched. There have been times where he's admitted to getting caught up in the thrill of building something new, but from an outsider's point of view, he's always driven toward the same end. Martin has made choices to scrap ideas, revisit functioning pieces, and compromise on novel concepts because he knows where the Marble Machine X (MMX) is going.

We should be approaching projects the same way. Never lose sight of the end goal and be willing to make hard choices for the greater good.

Proofs of Concept

Martin spent two years creating the first marble machine. It worked long enough to film a hugely successful music video but was not robust enough to make more music or tour with. He made the extremely difficult decision to retire two years' worth of effort and start from scratch. That decision will ultimately enable new music, new videos, and a world tour, but there has been a huge effort involved with getting there.

How often on our projects do we decide to slap Band-Aids on a proof of concept that was never meant to scale in an effort to save cost and time? We need to consider putting forth a real effort and produce something that's built to last.

Small Experiments Drive Innovation

Getting the vibrato figured out for the vibraphone proved to be a far more difficult undertaking than I thought it would be. Originally, the marble machine had a box with a set of sliders that moved back and forth in time with the wheel, creating vibrato as the box was repeatedly opened and closed beneath the vibraphone bars. Normally, vibrato is created on a vibraphone using a pipe with a spinning disk at the pipe's entrance that sits just below the bars. After many experiments with a single vibraphone bar and pipe, Martin landed on a design that fit in the machine and allowed for a spinning disk. The issue then was getting the whole thing mic-ed up. One microphone at the top of the pipe didn't properly catch the vibrato, while one below the spinning disk picked up too much interference. Two microphones created sound conflict that could be sorted out in post production, but was rough on the ears live. After several iterations, Marin was getting a little frustrated; he had sunk a lot of time into this very specific problem. Maybe the vibraphone didn't need vibrato? But taking that away would mean losing a key characteristic of the instrument.

This was tough. So difficult in fact that the previous approaches were more or less impossible without significant redesign to the machine as a whole. Martin decided to think a little outside the box and ended up going with a third party, custom microphone set that produced vibrato digitally. It meant losing a visually appealing set of pipes that made the machine look even more complex than it already was, but saved on set up and complexity while also guaranteeing consistency of sound quality. Using a series of small experiments ultimately saved countless hours and heartache that may have been a threat to performing with the machine, but it took a lot of time and dedication to get there. He used the experiments to prove a negative, and then considered alternate, if less-than-ideal, solutions. The final approach involved compromise that saw a loss in the natural sound and visual draw of the machine in favor of overall performance ability. I'm hoping the parallels to our projects are obvious.

Use small experiments to prove possibility, use said experiments as a launch pad for innovation, and be flexible enough to sacrifice what’s cool for what’s best.

Systems Thinking

The Marble Machine X is a single, complex system. An input becomes an output that again becomes an input as we follow the journey of a single marble. Starting at the loading chutes, the marble slowly descends as each marble before it is loaded into a drop chamber and subsequently released into the world to land on its intended instrument. After falling and hitting the vibraphone, for example, the marble bounces into a wire catch and falls down a chute that feeds into another chute, ad nauseum, until finally reaching the bottom of the magnetic lifts. Before being loaded on the fish stair that will raise the marble to the top of the machine, a set of oppositely polarized magnets are spun near the marble as it falls from the magnetic gear, demagnetizing it and allowing it to move freely. The marble’s next stop is the "fish stair", a series of individual sloped steps that raise and lower the height of the stairs directly preceding it. This allows a marble to be loaded on the first step and slide down onto the second, which then rises to the height of the third step where the marble again rolls down onto the third step which rises to the fourth, etc. After reaching the top of the steps, the marble rolls back to the loading chutes where it falls into the first available slot and begins its journey down the length of the machine once again.

The marble, in this case, can be a stand in for whatever it is in your project that needs to move through the system. Inputs to the system must flow from each step so seamlessly that it's impossible to fall out of or prevent the system from working. If a marble in the machine at any point leaves the enclosed system, then we've got an imbalance that will eventually lead to system collapse. More than just leaving the system, what if a marble were to become stuck in a loading chute? You'd have an entire note or drum pad that can't be played. If a marble becomes stuck in a gear of the fish stair then you'd run the risk of damaging the main flywheel. What I'm getting at is that the integrations between each piece in your system must be considered holistically. Perfecting the marble drop but neglecting the loading chutes would create a system where music can only be maintained for as many marbles were preloaded in the machine.

Make sure you understand the path from input to output or risk system failure in the long run.

Scaffolding

At Martin’s own admission, the original marble machine was created mostly on the fly. Pieces were created, changed, added, and scrapped based on a series of constantly shifting variables, requirements, and limitations. The fragility of the original design can be partially attributed to the ad hoc approach to creation. Before construction of the Marble Machine X had even started, Martin was inundated with feedback from engineers in the community calling for a defined back-log of parts, tracking of whether pieces had been created already, and requests to be involved in construction. Martin answered these calls in a few ways.

The first was to figure out the best way to accept feedback from the community at large. He tried a Patreon where only paying community members could comment, a stickied YouTube comment where all feedback needed to be given in the same place, and finally settled on a Reddit community. Deciding on the feedback mechanism wasn't a quick task, each iteration needed time to prove it's worth or insufficiency before settling or moving to the next, but since settling on a Reddit community dedicated to the machine gathering input has been streamlined and a burgeoning community has grown to over 7,000 members. Martin has taken an extremely organized approach with regards to the backlog of parts. He, with the help of engineers in the community, designed each of nearly 4,000 parts in a CAD tool and stored them by name in a Google sheet. The sheet also includes whether the part has already been physically created, whether they encountered a design problem in the CAD tool, and a unique ID so that the piece can be stored in a bag on a shelf and found quickly. As you can imagine, without this clean and thorough backlog, keeping track of 4,000 pieces would be impossible for a single person or even a small team.

Setting up scaffolding around a project can lead to its ultimate success or failure. It may take some time to solidify the feedback mechanisms and create a concrete backlog of features, stories, and tasks, but taking the time to get it right before you start may make all the difference.

Incorporating Feedback

Martin tackled the involvement of external engineers in an elegant way. The end user of the MMX is Martin himself. He has known from the beginning that he's the one that needs to be happy with the design, sound quality, and functionality of the MMX and has made sure that other's opinions have been taken into account without superseding his own thoughts. He happily takes feedback from the community where appropriate, but ultimately knows what he's shooting for and is careful to not let the community sway him. In my experience, this is a skill that isn’t talked about often but is crucial to success both professionally and personally. How are we supposed to know when to accept and incorporate feedback, and when to nod our heads and smile while understanding that some feedback will not always be to our ultimate benefit? It's something that I'm still trying to figure out so let me know if you have ideas.

Martin has accepted help in machining pieces several times and always makes sure that the people who made those pieces for him get a personal shout out in his videos. What's cool is that he doesn't always use those pieces in the form that they're given him. For example, Martin requested help in creating the marble drop chutes, and an external member of the engineering team machined them and sent them to him completed. On reception of the pieces, Martin realized that there were some changes he needed to make, so he thanked the creator, and then cut them into little bits and only used the parts that he needed. Eventually Martin scrapped the chutes altogether and is planning on a totally different approach to dropping marbles. I've seen examples where a colleague has been afraid to make changes to a peer's creation for fear of offending them, and I think that kind of sensitivity is important.

Find ways to make sure your team feels validated and appreciated while not being afraid to make or request changes to their contributions.

In Conclusion

These are just a few of the things that I've learned from watching Martin and his team build the Marble Machine X, and I'm sure that there's more I'll pick up in the future. I'm excited to see this effort come to fruition and hope that I'll be able to catch a live show with this marvel of music and engineering when they go on tour.

Please feel free to reach out to me if you have any questions and be sure to give Martin and Wintergatan your support by watching their videos, subscribing to their YouTube channel, or even becoming a Patreon supporter.

Senior Software Engineering Manager at Pariveda Solutions (Cloud, AI/ML, Healthcare, & Emerging Tech Enthusiast)

4yGreat insights, Johnson!