All Hail Dead Week, the Best Week of the Year

The week between Christmas and New Year’s Eve is a time when nothing counts, and when nothing is quite real.

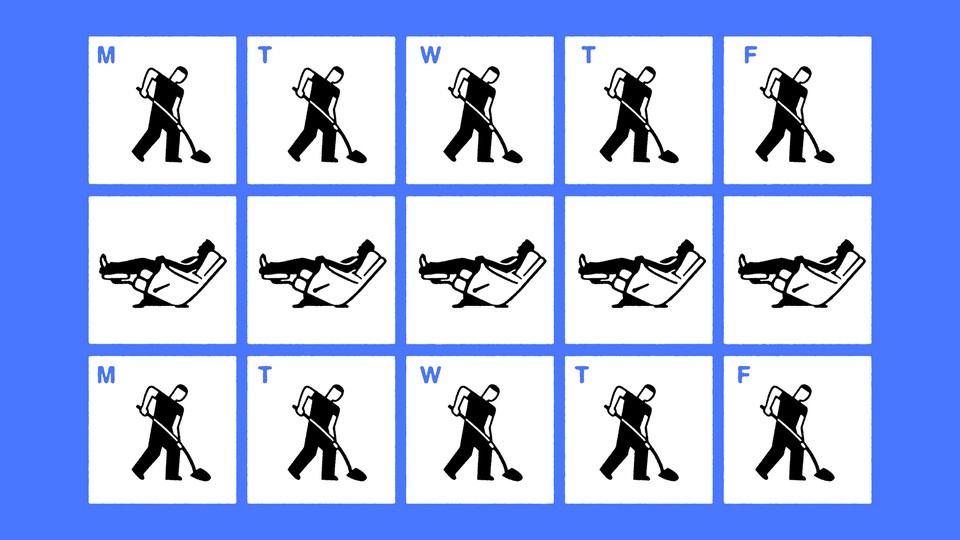

Christmas is over and we have arrived at the most wonderful time of the year—nominally still the holidays, but also the opposite of a holiday, a blank space stretching between Christmas and New Year’s Eve when nothing makes sense and time loses its meaning. For many of us, this is the only time of year when it feels possible, and even encouraged, to do nothing. I look forward to it all year long.

The time from December 26 until the afternoon of December 31 is generally considered part of “the holidays.” Kwanzaa, and very occasionally Hanukkah, falls during this period. But for many of us, whether still celebrating holidays or having just finished Christmas festivities, this week is like a long hangover. To some degree, I think all of society feels a little aimless during these few days. We’re waiting for the new year, with all its resolutions and hopes for starting over, but we’re not quite done with the old one. In between the end of the old year and the beginning of the new one is this weird little stretch of unmarked time. For most people, this week isn’t even a week off from work, but at the same time it also isn’t a return to the normal rhythm of regular life. Nobody knows what to do with this leftover week, awkwardly stuck to the bottom of the year. I call it “Dead Week,” a time when nothing counts, and when nothing is quite real.

The British call this week “Boxing Week,” an extension of the more formal holiday Boxing Day, on December 26. Boxing Day is an older tradition that may stem from wealthy families giving presents to their household staff the day after Christmas; in its current form, it is a day to box up and get rid of extra stuff, or regift unwanted gifts. Boxing Week has become an excuse for Black Friday–type sales and the accumulation of more stuff. In Norwegian, Dead Week is known as romjul, a word that combines the Norse words for “room” or “space” and Jul, or “Yule”; it literally means “time and space for celebrating the yuletide.” But it also echoes the Old Norse word rúmheilagr, which means “not adhering to the rules of any particular holiday.” The week has neither the religious gravity of Christmas nor the flat-out party atmosphere of New Year’s Eve, but is stuck halfway between one and the other. Dead Week is a holiday without expectations, which are how we usually understand holidays. Romjul traditions include general holiday activities such as partying, eating a lot, visiting family, and resting.

American culture doesn’t have an official name for this time (though maybe Dead Week will catch on), but we celebrate it all the same, by eating cheese and cake for breakfast, getting drunk at inappropriate hours, not looking at calendars or clocks, forgetting what day it is, wearing outfits that make no sense, ignoring our phones, and falling into a pointless internet rabbit hole for hours. Lots of people have either just returned from family visits or are still there, stuck in the half-familiarity of being an adult in the spaces of childhood. We celebrate Dead Week by having no idea what to do during Dead Week and, within that confusion, quietly luxuriating in what might be the only collective chance for deep rest all year.

Most people do work during Dead Week in the United States. In recent years, a few companies have shifted to giving employees the entire week off, a tacit admittance that it is both still part of the holidays and a useless time to expect any kind of productivity. But far more workers have no possibility of taking this time off; in retail, for instance, this is one of the busiest and most hellish weeks of the year.

Even so, it is still the closest thing we have in our society to some kind of a communal pause. Nothing is ever as quiet as it is during those few days, cities emptied out and small towns sleepier than usual, people drifting around not interested in accomplishing anything. There is a collective sense that, for these few days, we are not going to do any more than we must. It doesn’t really matter if you don’t brush your hair, if you stay up all night, if you don’t send that work email. Many people aren’t checking email anyway, and nobody wants to be asked to do more work than they absolutely have to.

Dead Week isn’t a week off for everyone, or at least the thing it is a week off from isn’t work. Rather, it is a week off from the forward-motion drive of the rest of the year. It is a time against ambition and against striving. Whatever we hoped to finish is either finished or it’s not going to happen this week, and all our successes and failures from the previous year are already tallied up. It’s too late for everything; Dead Week is the luxurious relief of giving up.

These five days are the purest unit of nothing time that the year offers. Nothing time is different from free time; Dead Week is not a vacation and not a holiday, but we are afforded so little truly unmarked and nonurgent time that five days when nothing really matters can feel like something more precious than either one. In American society, we spend most of the year receiving the message that we are supposed to try harder, do better, achieve more than the person next to us, rack up a bigger pile of stuff and a longer list of accomplishments. For once, the insistent push to hustle and climb grows quiet, and there is a break from the screeching sense that every day must be optimized for efficiency.

My favorite part of Dead Week is getting up early, drinking coffee, and looking ahead to the long stretch of nothingness that fills the day. The nothingness doesn’t have to be slothful; sometimes I leave the house and sometimes I don’t, but the point is that it doesn’t matter. If I don’t go outside, I don’t feel bad about it, and if I do, everybody else I encounter looks equally confused and at loose ends, frittering away these leftover days. It is the only time of year when the days feel slow to me, when the time outside of whatever tasks I have to do does not somehow vanish into further worry and busyness. It is the only time I don’t feel like I am perpetually late to my own life, and that easing of guilt offers a deeper rest than any vacation would.

Dead Week is forgiving—everyone loses track of time; everyone forgets; everyone decides not to worry about it until January. These days at the end of the year offer a kind of grace, a time when simply existing is enough, outside the records of success and failure.