(Image CC BY-NC 2.0 by Christopher Michel)

In which guest blogger Lars Doucet provides a translation of the article “Den nye oljen” [The new oil] by Anne Margrethe Brigham and Jonathon W. Moses.

Translator’s Preface

Hi, my name’s Lars Doucet and I’ll be your guest blogger today here at SLIME MOLD TIME MOLD. Today is the 17th of May, Norwegian Constitution day, so I asked SMTM if I could share a fascinating paper from my motherland, publicly available in English for the first time right here. Thanks to SMTM for the venue, and to Jonathon and Anne Margrethe for letting me translate and share their work.

Norway confuses and annoys doctrinaire Capitalists and Socialists alike by pairing a dynamic market economy with an expansive social welfare state. But lurking unnoticed in the background is a third economic philosophy that has profoundly shaped this Nordic kingdom–Georgism. Georgism is a school of political economy that embraces both the free market and the private ownership of capital, while also attacking passive rent-seeking. Its chief aim is to ensure that those things which no man has created (such as land and natural resources) be put to the common benefit of all rather than monopolized by private interests. I’ve written previously on this subject over at Astral Codex Ten, Game Developer magazine, Naavik, and the Progress & Poverty substack. You can find a curated standalone collection of my work at gameofrent.com.

In online discourse, many people’s introduction to Georgism is the tongue-in-cheek meme, “Land Value Tax would fix this.” But there’s a lot more to Georgism than LVT, and Norway is a particularly instructive and successful example of how to apply Henry George’s lessons to a different kind of “land” – natural resources. Modern Norway is an energy powerhouse whose domestic economy runs almost entirely on zero-emission sources (mostly hydro-power). At the same time, their export economy houses one of the most economically successful and technologically advanced petroleum industries in the world.

The Norwegian hydro-power management regime was explicitly set up by Norwegian Georgists in the early 20th century, based on the idea that the nation’s water was the common property of the Norwegian people. These officials realized that when access to a natural resource is limited–either naturally through physical scarcity, or artificially through government regulation–an abnormally high rate of return known as a “resource rent” arises. This super-profit arises not from a private actor’s contribution of labor or capital to the free market, but instead from the monopolistic leverage that limited access to a bounded resource naturally gives.

So who should receive these bountiful “resource rents?” The resource’s owner of course–the Norwegian people. This doesn’t mean that private companies can’t be involved, quite the opposite in fact–just so long as they keep their hands off the resource rents. Norway’s Georgist management regimes for hydro-power and petroleum aike were founded on the same principles. Their success is an empirical refutation of the theoretical claim that private companies won’t be incentivized to discover and efficiently extract resources unless they’re allowed to keep the resource rents.

Norway now sits at a crossroads. The oil will not last forever, and the country cannot remain dependent on petroleum if it wants to transition to a green economy and tackle climate change. Norwegian politicians therefore seek a “New Oil” in emerging natural resource sectors–specifically aquaculture (fish farming), wind and solar power, and “bioprospecting,” the mining of organisms for useful new chemical compounds (think penicillin). Unfortunately, Norwegian policy makers have lost touch with their Georgist roots and have set up management regimes for these new sectors that will allow private companies to capture the entirety of any emerging resource rents. This means that even if one of these sectors becomes a “new oil,” the windfall profits will go not to the Norwegian people, but instead to literal “rent-seekers” passively extracting monopoly profits at public expensive.

The authors of “Den nye oljen” persuasively argue that Norway must learn from its own successful tradition of Georgist resource management policy in order to chart a sustainable path to the prosperous future it deserves.

The original Norwegian text can be found here:

https://www.idunn.no/doi/pdf/10.18261/issn.1504-2936-2021-01-01

If you find this article interesting, please look for the authors’ upcoming book, The Natural Dividend: Just Management of Our Natural Resources (Forthcoming, 2023, Agenda Press), which expands this argument to apply to the entire world, not just Norway, using case studies from around the globe.

The New Oil

Anne Margrethe Brigham (Senior Researcher, Ruralis)

Jonathon W. Moses (Professor, Department of Sociology and Political Science, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU)

English translation by Lars Andreas Doucet (independent researcher)

Copyright © 2021 Author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC-BY-NC 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

Abstract

Norway’s future economy will depend less on petroleum. There are at least two reasons for this: petroleum is a nonrenewable resource, and the need to limit climate change. For these reasons, the Norwegian authorities are seeking out greener opportunities in the fields of bioeconomy and renewable energy. This article considers how the management of key natural resources affects the opportunities available for funding Norway’s welfare state in the future. To do this, we compare the regime used to manage petroleum with those used on wind and hydropower, aquaculture and bioprospecting. The different management regimes play a decisive role in determining the size and scope for taxation of the resource rent that these resources produce. Our analysis shows a break in the Norwegian management tradition for natural resources. The government has opted out of the successful management regimes for hydropower and petroleum and replaced them with regimes that can neither ensure public control nor taxation of the resource rent from wind power, aquaculture and bioprospecting. We conclude that the current management regimes in these sectors cannot contribute to a level of public wealth that can match the one that Norway has become accustomed to from oil.

Keywords

Resource rent, renewable energy, aquaculture, bioprospecting, natural resources

Introduction

Norway has begun to accept a sobering truth: in the future our economy must become less dependent on petroleum; not only because it is a non-renewable resource, but also because of increasing political pressure to reduce our nation’s contributions to climate change. This will not be easy, as we are dependent on the petroleum sector for both jobs and government revenue. Political authorities (and others) have therefore begun to actively seek a new, greener, economic foundation upon which Norway’s future may be built. Many hope to have found this alternative foundation in the so-called “bio-economy”, which, roughly speaking, can be understood as value creation based on the production and exploitation of renewable biological resources (NFD, 2016, p.13),[1] and renewable energy sources.

[1] In the government’s Bioeconomy strategy (NFD, 2016, p.13), bioeconomy is defined as “sustainable, efficient, and profitable production, extraction, and utilization of renewable biological resources for food, (animal) feed, ingredients, health products, energy, materials, chemicals, paper, textiles, and other products. Use of enabling technologies such as biotechnology, nanotechnology and IKT [information and communication technology] are, in addition to conventional disciplines like chemistry, central to development in modern biotechnology

Within the bio-economy and renewable energy fields, there are three sectors in particular that are often put forward as potential “green” replacements for oil and gas in Norway: aquaculture, wind- and hydro-power, and bio-prospecting. The optimism for these sectors is based on the country’s absolute advantages in terms of “clean” natural resources. In the first sector, aquaculture, Norwegian companies are already world leaders in salmon farming – see e.g. NFD (2015). In the second sector (renewable energy) Norway has a long tradition of exploiting its hydro-power potential, and now is turning its technical expertise to wind power. The third sector, bio-prospecting, is less well-known, but seems to have captured the attention of politicians who hope to encourage research and investment that will allow Norway to play a vital role in this sector in the future (NFD, 2016 and 2017). The government has prepared a strategy to encourage business growth in the bio-economy (see NFD 2016), in order to contribute to job growth as well as the financing of Norway’s comprehensive public welfare system.

Many people trust that Norway’s high standard of living can be maintained by a well-managed transition from a petroleum-based economy to one based on renewable resources. Aquaculture, renewable energy, and bioprospecting alike provide hope for an attractive economic future, because we can expect the demand for renewable resources to increase going forward. The potential for “resource rents” from Norwegian renewable resources have been brought forward in at least two recent NOU’s: NOU 2019:16 (concerning hydropower) and NOU 2019:18 (concerning aquaculture) [TRANSLATOR’S NOTE: “NOU” stands for “Norges Offentlige Utredninger”, meaning “Norwegian Public Reports,” where the government or a ministry creates a committee or working groups to report on different aspects of society.]

The Norwegian government’s ability to consistently collect resource rents has been crucial to harvesting public benefits for all the Norwegian people. The collection of new resource rents ought to be a vital part of the motivation in shifting to an economy based on “green” natural resources (sooner than shifting to e.g. industrial production or a service economy). This raises an important question, which is the motivation behind this article. Is it reasonable to expect that these new sectors will be able to bring forth tax revenue from resource rents in line with what Norway has generated from the oil business?

It is not easy to answer this question, since resource rents are shaped by the economic value of the resource (which can change significantly over time from market fluctuations) and the underlying management regime. Even if it is not possible to predict the future economic value of a natural resource, we can still consider whether the management regime is able to recognize and ensure a potential resource rent, should it arise. This article addresses this issue precisely, by comparing the management regime used in the petroleum sector with the regime used in aquaculture, wind- and hydropower, and bioprospecting. This involves us acknowledging that the management regime for petroleum has been a success. We therefore consider the degree to which this regime has been transferred to the management of alternate resources that many hope can contribute to the financing of our future welfare state. In other words, this is a survey of whether the Norwegian people’s economic interests are properly secured in these four sectors.

In this article we show that the present method for managing these renewable resources is very different from the one used for petroleum. Even if the commercial value of these renewable resources today is low compared to petroleum, it is likely that their relative worth will grow in the future. Since the potential for resource rents changes significantly over time, in line with changing market conditions and ongoing technological progress, we will not attempt to estimate the precise size of future resource rents in these sectors. Nevertheless, it can be reasonable to expect that these natural resources will be even more valuable in the future, and that the potential resource rent will grow, even if it would go too far to say that their worth would be close to what the oil sector gives us today. It is therefore important to discover whether the authorities have the ability to collect this value on behalf of the community. We find that the authorities have traded away the successful management regime typical of the oil sector, and replaced it with regimes that can secure neither commensurate public control nor similar tax revenue from the wind-power, aquaculture, or bioprospecting sectors. It is only in the hydro-power sector that (a portion of) the resource rents are reclaimed by the community.

For over a century the authorities have protected public ownership of the community’s natural resources, and collected the resulting resource rents from private companies. We feel it is remarkable that the authorities now abandon this system for our renewable resources, and in its stead have introduced a number of competing management regimes that focus primarily on increased efficiency. As a consequence, there is a real chance that private investors (both Norwegian and foreign) will be allowed to capture the full resource rents that are created by Norway’s management of natural resources.

The argument that follows has five parts. In the first part we define what we mean by “resource rents,” and how they can be measured and obtained on the basis of the work of Henry George (1886). This makes up the theoretical foundation for the survey that follows. In the second part we give a short description of the method we have used. In the third part we document Norway’s present dependence on the resource rents of petroleum, and the economic benefits that Norway has harvested from the oil business over time. The fourth part of the article gives an overview of the management regimes in the three renewable “candidate resources” that Norway hopes can replace petroleum in the future: aquaculture, renewable energy production (wind and water) and bioprospecting.

The fifth part concludes that Norway’s “new oil” must be managed in a manner that looks beyond the successful management regime of “the old oil.” When we compare the potential for public value creation across the old and new resource sectors, it is clear that our “new oil” cannot generate a public fortune (or be subject to public control) in a way comparable to what we have been used to. This is because any eventual resource rent, regardless of its size, will not be collected for the benefit of the public, but instead will be captured by the private sector.

On Resource Rent

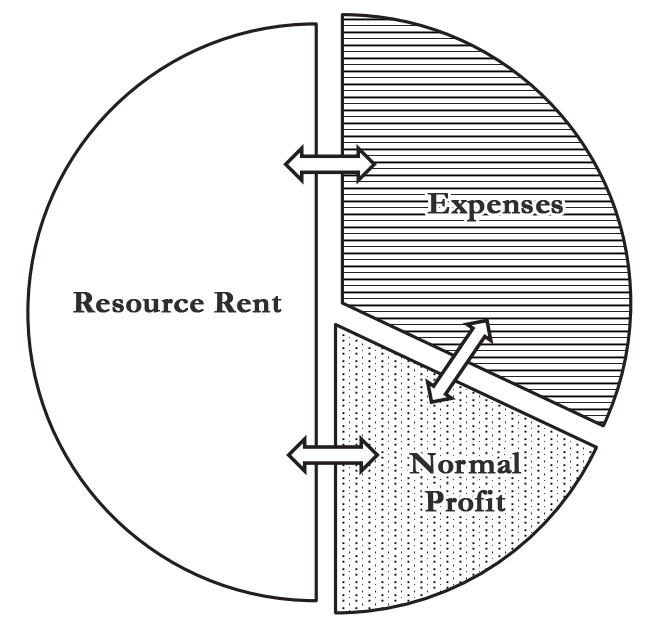

Resource rent is an extra-ordinary value derived from the use of a natural resource, and it is measured by subtracting all costs, as well as a normal-sized profit, from revenue (see figure 1). The reason that natural resources can produce resource rent is that they are limited by nature and/or politics. They are limited by nature in that there are only a certain amount of them (with variations in quality and productivity), while they are limited by politics when the authorities regulate their exploitation and access. When it is not free for just anyone to invest in the exploitation of natural resources that produce positive returns, a sort of monopoly is formed which in turn contributes to an artificially high profit for the “chosen” producers. As Greaker and Lindhold (2019, p. 1) write, it means “…that one can achieve positive profit on the basis of a natural resource over a longer period of time, without new providers wanting to establish themselves. In other words, the limited access hinders the free establishment that otherwise would have pushed down the profit from the operation towards a normal return on capital.” Which is to say, the regulation itself causes the profit to be greater because the market prices will become higher than they otherwise would have been (see Skonhoft, 2020).

The potential for resource rent is also determined by market forces. Not all natural resources are capable of bringing forth notable amounts of resource rent: sometimes it is simply too expensive to gain access to or produce the resource, relative to the price it fetches in the market. Other times the way in which the resource is managed causes its exploitation to be too expensive or lead to overexploitation (i.e. the tragedy of the commons) [3]. Therefore it is difficult to separate resource rent from the method the community uses to regulate access to its resources [4]. Speaking very generally, political authorities have two main tools for achieving their management goals: ownership, and collection/taxation.

[2] If there was free competition in the market for natural resources, companies/actors engaged in that market would not be able to harvest an abnormally large return. The fact that international oil companies are among the most profitable companies in the world, is in and of itself an indication that there is not free competition in the petroleum markets. Similar cases of disproportionally large incomes are emerging in the aquaculture sector.

[3] See for example, Brox (1987), where Norwegian wild fishery resources and agriculture yielded negative resource rents.

[4] Given our broad definition of resource rent, above. In The Condition of Labor, George (1982 [1893], p.13-15) distinguishes between “monopoly ground rent” and “natural ground rent”–where the latter gives birth to unusually large profits which simply stem from location. See Giles (2017, p. 68). Others distinguish between the ground rent and the regulation rent. See, for example, Skonhoft (2020). [TRANSLATOR’S NOTE: in the original Norwegian, the authors use the term ‘grunnrente’ throughout this piece, which I have consistently rendered (at their indication) as ‘resource rent’. This is what the term effectively means in Norwegian, but it also corresponds perfectly to what Henry George meant by the term ‘ground rent.’]

Ownership

The first tool is used on property rights, and concerns various forms of contracts (for example, licensing agreements, production sharing agreements, licenses, and patents). These tools limit access to resources and help to establish resource rents. While the actual motivation for limiting access to a resource can be to protect it from over-exploitation (for example), the regulation can nevertheless create a resource rent.

It is important to underscore that natural resources are owned by the people. Public ownership of natural resources are anchored in Norwegian laws (and customs) more than a hundred years old, in addition to international agreements such as the UN’s resolution from 1962 concerning permanent sovereignty over natural resources and Article 1 of the International Convention of Civil and Political Rights (UN General Assembly, 1962; 1966). This was clarified in a supreme court decision from 2013, which stated that (wild)fisheries belong to the Norwegian people. For this reason the state has a responsibility to ensure that the people it represents get to enjoy the benefits of the value created from the resources that they own. In order to discover and produce these resources, as well as deliver them to market, the state often gives private business actors with expertise in the given sector (for example petroleum, fisheries, energy) permission to do it on their behalf. These companies receive in these situations a license (often called a “concession”) that ensures their access to use a limited amount of resources on behalf of the community of people who own them.

These licenses/concessions will naturally vary somewhat according to the resource’s characteristics. Some resources are renewable (e.g. waterfalls), while others are not (e.g. petroleum). Some resources are easy to recover, monitor, and control (e.g. aquaculture), while others are more volatile (e.g. wind and solar). Access to the more volatile resources like wind and solar can also be limited, something sailboat racers and sunbathers can attest to. As more and more of our common resources are transformed into market goods, it is important that the community asserts its rightful ownership of them before they are effectively privatized.

In order to attract relevant producers with the proper skills, the licenses/concessions must be generous enough to provide a basis for a healthy return on investment and labor. If they are sufficiently easy enough to obtain that they attract many producers in the market, the resulting (market) value of the licensed resource will be relatively low. This value, like the market value of anything else, is roughly determined by the supply of the resource available on the market, for any given level of demand. By limiting access to these resources the state is able to increase and stabilize their value, and in reality creates a monopoly situation. In this way even the harvesting of sea salt can secure a significant resource rent when the state restricts access [5]. Under such conditions where production is limited, the expected profit will be far higher than what is required to attract competent market actors. In other words, it is the licensing scheme that produces the “resource rent”, as George (1886, p.169) [6] simply described as, “the price of monopoly. It arises from individual ownership of the natural elements — which human exertion can neither produce nor increase.”

[5] Take for example Mahatma Gandhi’s salt march (Salt satyagraha) from 1930.

[6] George was of course not the only modern economist who was concerned with resource rents. He was also not the first (see, Anderson, 1777). He shared this interest with among others David Ricardo (1817), Nassau Senior (1850), and Karl Marx (1981 [1865], Vol 3, p. 882-813), but George was alone in making the taxation of land a central element in a political campaign for the redistribution of public wealth. See for example O’Donnell (2015).

Collection and Taxation

The second tool is used to secure the public a share of this resource rent, since it belongs to the community: “It is the taking by the community, for the use of the

community, of that value which is the creation of the community.” (George, 1886, p.431). To ensure that the licensed company is not left with the entire resource rent (which belongs to the community), the state must collect a portion of it [7]. This must be done in a way that undermines neither the incentive for private companies to do the job of extracting the resource (i.e., their profit), nor competitiveness in the international market. This can be done in several ways. One is to ensure that access to the limited resource (e.g. licenses) is evenly distributed across a number of small producers, and/or to require that local workers, technology, and subcontractors must be employed. Another way is to use purely economic means in the form of fees, royalties, and taxes.

Last, but not least, it is important that the size and structure of the instruments which secure the community’s portion of the resource rents can change over time. It is therefore important for political authorities to implement a licensing and taxation system that is flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances, and gives the possibility for updates (Moses and Letnes, 2017a, pp. 64-5). By spreading the awarding of licenses over time, and by giving shorter license periods (but long enough for investors to secure their legitimate returns and establish efficient production routines), the political authorities can ensure that the resource rents accrue to the community [8].

[7] This is especially important when the resource is non-renewable, as with petroleum. In these situations it is important to protect revenue from the sale of resources, and build up an alternative fortune when the one on the sea floor is reduced.

[8] Here we can give a little warning. Affected investors constantly insist that a resource rent tax threatens their ability to secure an acceptable return on their invested capital, hinders necessary investments, or provokes capital flight. See, for example, the statements from Geir Ove Ystmark, administrative director of Norwegian Seafood in Widerstrøm (2019). These threats, and active lobbying (see Kristiansen and Wiederstrøm 2019), reflect a general ignorance of the nature of resource rents and property rights (or a willingness to pull the wool over the public’s eyes). The authorities can secure a fair share of the resource rents in many different ways, and almost all of these are sensitive to the need to ensure investors and workers a fair return on labor, time and money, as the resource rent (by definition) comes on top of the normal return.

As we will see below, much of Norway’s success in the oil sector can be ascribed to a management regime that generated a resource rent, which has been taxed and used to finance the Norwegian welfare state. In contrast to many other countries, the Norwegian authorities recognize that the majority of (if not all) of the resource rents should return to the community, who own the underlying resource. (e.g.: Finansdepartementet, 2018a; see also NOU 2019:18, p. 9). What many are not clear about, is that the resource rent regime in the oil sector builds upon the licensing and taxation system from hydropower:

Norway’s petroleum resources are the Norwegian people’s property and shall be for the benefit of the whole society. This was the starting point for the management of petroleum resources over the last 50 years. The licensing legislation from 1909 concerns the regulation of hydropower, but has also been relevant for the oil business. The legislation provided for the right of restitution, emphasized that it is the Norwegian people who own the water resources, and that the resource rent should accrue to the community. The same principles have been followed in the management of petroleum resources. (OED, 2011, p. 5)

The politicians who developed this system over 100 years ago, relied on the American economist Henry George [9]. The acceptance for the collection/taxation of resource rents can weaken if the underlying understanding of natural resources as the property of the community is lost. In this respect it is noteworthy that the recent reports on the taxation of hydropower (NOU 2019: 16) and aquaculture (NOU 2019: 18) clearly did not have a mandate that included a reflection on the political and moral justifications for ensuring that the resource rents accrue to the community as a whole.

[9] It is not perfectly clear how large of an influence George had, since most of the discussion around the original licensing law concerned the right of restitution and to what degree it was in line with the constitution’s protection of private property rights, but we know that George’s works were translated by the prominent leftist Viggo Ullmann, and that Ullman was the first leader of the “Henry George movement” that published the magazine Retfærd. Tidsskrift for den norske Henry George bevegælse [Justice. Journal of the Norwegian Henry George movement]. Other well-known and influential people in this movement were Arne Garborg and Johan Castberg. For more about the Georgists’ impact on Norway’s hydro-power regime, see Thue (2003, chapter 3).

Method

We are interested in finding out to what degree politicians have tried to transfer the management regime in the petroleum sector to the bio-economy and renewable energy sectors. Given the success Norway has had with its petroleum management, and the explicit desire to finance future public spending with revenues from the bio-economy and renewable energy sectors, we should believe that the Norwegian authorities will want to use the most important instruments from the petroleum management system in the “New Oil” sectors. After all, it was exactly this which happened in the 1960’s and 70’s, when the fifty-year old licensing regime concerning hydropower was taken and used for the new petroleum sector.

We have chosen three cases studies from the bio-economy and renewable energy sector: aquaculture, hydro- and wind-power, and biotechnology. This does not mean that they are the only relevant cases, and we had initially thought to include a number of other sectors (such as agriculture, forestry, solar energy, and fisheries). We landed nevertheless on the above, not only because they are renewable, but because they have been emphasized by the authorities as especially important for Norway’s future, and because the growth potential of each of them is dependent on innovation in both technological and legal developments.

We compare and contrast the existing management regimes in these sectors with regards to the two tools for capturing resource rents that we described in the theoretical review above, namely ownership and collection/taxation. We look at four specific aspects of management:

- Is public ownership of the resource explicitly recognized?

- Do the authorities control access to the resource, and if so, how?

- Have they introduced tax rules that enable the collection of eventual resource rents?

- Have they actually collected any resource rents that have appeared?

Points three and four are not only important in sectors where it has already been established that resource rents exist, but also in sectors that today have relatively poor profitability. This is because it will give public officials the authority to collect (parts of) the resource rents if market conditions change such that these sectors also begin to generate disproportionately large profits (so-called “super-profit”). Our focus is therefore not on the current size of the resource rent, but on the state’s abilities to recognize a resource rent as it arises, and its right to reclaim it from private to public hands.

The analysis is supported by three kinds of sources. The information about the petroleum management sector is largely based on the authors’ prior research [10]. When it comes to the other sectors, we have relied on available literature and interviews with relevant private, public, and political actors in the autumn of 2019 [11]. In addition to collecting information such as we could use indirectly in our analysis of the management regimes, we used interviews (and follow-up conversations) to map out further relevant primary sources and documents within each sector (see the list of references). Next, we analyzed this documentation with regards to ownership and collection/taxation, in order to assess the regime’s potential for capturing resource rents. It soon became clear to us that there was a large amount of secondary literature around the regulatory processes, but that this literature for the most part dealt with the environmental (and sometimes moral)[12] consequences of the management regimes. Even though this literature is important, it is not directly relevant to our purpose, so to avoid diluting our argument we have not referred to this particular literature to any significant degree.

[10] See for example Pereira et al. (2020); Moses (2010 and 2020); Moses and Letnes (2017a and 2017b); and Edigheji et al. (2012).

[11] After conducting a literature review and acquainting ourselves with the relevant documents, articles, and books, we wished to collect information from key people in Norwegian natural resource management that could elaborate on what we found in this literature. We therefore created a list of 13 experts who had extensive experience and knowledge related to regime management in aquaculture, renewable energy, and bio-prospecting. This expertise was based on factors such as their official role, professional competence, education, or experience. From this pool of thirteen, six experts were ultimately interviewed (either personally, via video conference, and one person by e-mail). Thereafter we used the snowball method to include a larger cross-section of experts in each of the three sectors, which we contacted with less formal inquiries (see, e.g., Van Audenhove, 2007; Bogner et al., 2009; Meuser and Nagel, 2009). The information that was obtained was used to identify additional literature, and as a backdrop for understanding it. The interviewees were promised anonymity in accordance with permission from NSD, and we therefore do not quote them, and we have not seen the need to include anonymized statements. The formal NSD permit and interview guides are available, upon request, from the authors.

[12] See for example Sagelie et al. (2020).

Norway’s oil dependence

When it comes to the collection of resource rents, Norway’s petroleum management has not changed significantly over time [13]. The management regime is still based on a system of allocation of licenses for offshore exploration and production which is intended to limit the number of actors and the amount of oil and gas that is recovered from the seabed. In the early years, when the authorities were unsure whether they were even going to find any significant oil reserves, the government was eager to allocate many blocks and offered very lucrative terms (e.g., low taxes). The intention at the time was not to secure the resource rents (which were still quite uncertain), but to try to attract the necessary international expertise to find and recover any resources. At this time, most of the state’s oil revenues came from royalties (in addition to ordinary corporate taxes).

[13] This part builds upon Moses and Letnes (2017a) to a large degree.

After it became clear that there were significant amounts of oil and gas on the Norwegian continental shelf, the power relationship between the Norwegian authorities and the foreign oil companies changed. The authorities could now be more strategic and make greater demands with respect to the allocation of licenses. This resulted in, for example, fewer blocks being laid out at once, and the most promising licenses/concessions being given to Norwegian companies. In short, the conditions changed to benefit Norwegian producers, Norwegian authorities, and the Norwegian people. This was completely in line with Norway’s “10 oil commandments” (OED, 2011, p.8) that laid the foundation for the development of Norwegian oil expertise (and capital), and made possible the establishment of Statoil (now Equinor).

Today the petroleum management system is not as explicitly political, but it has retained a good deal of its original building blocks. In order to secure itself a part of the resource rents that are created within the licensing system, the authorities use a variety of taxes and fees, although the content and scope have changed significantly. Today the oil companies that operates in Norway must pay the ordinary corporate tax (which is 22%, but has a generous depreciation scheme to incentivize further development). Additionally, after a so-called “lift” is subtracted from income (as an incentive towards investment), the remaining tax base is subject to a petroleum resource rent tax of 56% (see Moses and Letnes, 2017a, p. 104; Deloitte, 2014, p.16). In reality the petroleum producers in Norway are effectively subject to a tax rate of 78% (OED, 2019). This high tax rate is used to ensure that the resource rent, which is a consequence of Norwegian petroleum management, is returned back to the community which owns the underlying resource [14]. Oil companies still receive a significant return on their investments; the oil workers are still able to secure favorable wages and safe working conditions; and the environment is still protected–but private companies are not allowed to retain the entire resource rent.

[14] While the majority of Norway’s oil revenue comes from these taxes, a significant portion (around 30-40%) come from direct (co-)ownership of licenses that have already been granted (so-called SDØE). For an overview of the sources of Norway’s petroleum revenues, see Moses and Letnes (2017a, p. 101, figure 5.4)

It is important to note that the Norwegian authorities have used the licensing system–the power to give certain chosen actors exclusive access to a limited resource–as a tool to achieve a variety of political goals. A few examples of such goals are requirements to use Norwegian workers and subcontractors, protections for the environment and workplace safety standards, investments in Norwegian research and development (R&D), as well as to ensure that portions of the resource rent from petroleum accrue to the Norwegian people. Over time many of these explicitly political goals have faded, among other reasons because Norwegian companies no longer need special conditions or protections in order to compete with larger international actors, but the way in which Norway collects resource rents from petroleum extraction has not changed significantly since the 1970’s.

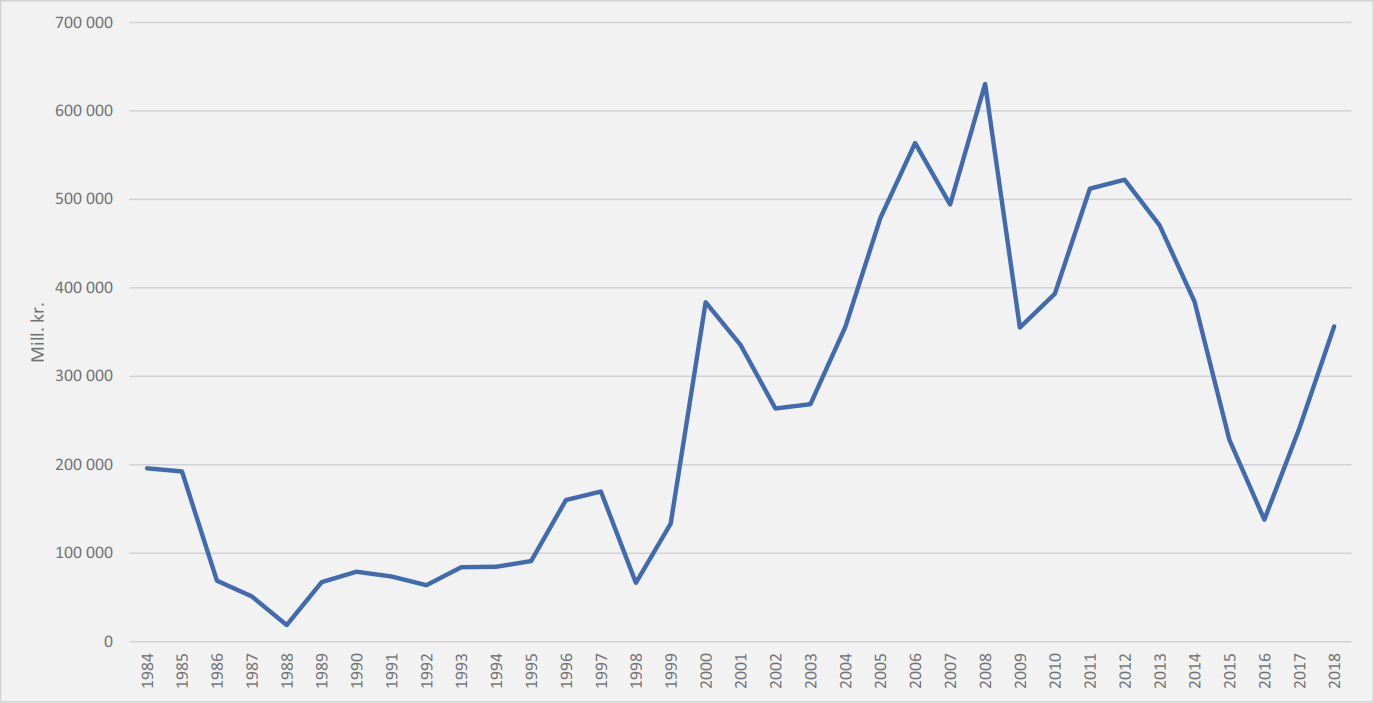

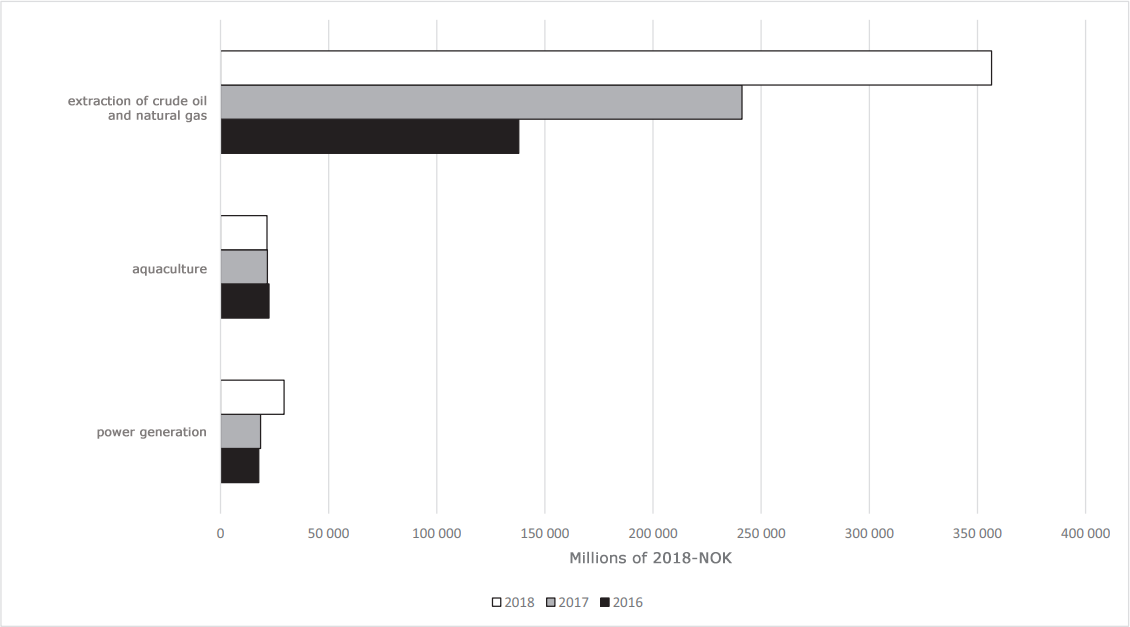

The result is that Norway has become an affluent country, and much of the oil fortune stems directly from the tax on resource rents. Because this is affected by the global price of oil, it varies significantly from year to year. In a survey of Norway’s resource rents from petroleum extraction, Greaker and Lindholt (2019) estimate the resource rents for 2018 to be nearly 360 billion kroner [~38 billion USD], down from a peak of over 630 billion kroner [~67 billion USD] in 2008 (see figure 2).

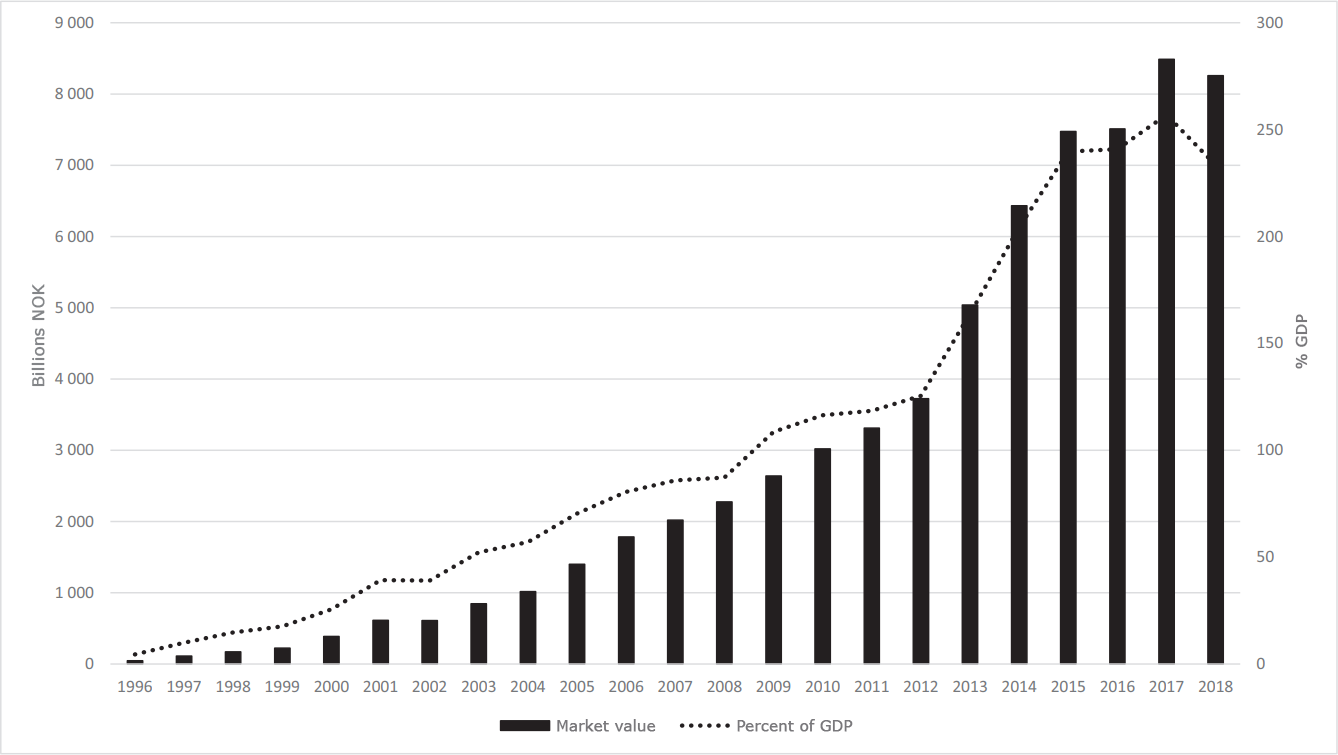

Now, it is not the case that the entirety of the resource rent accrues to the state; some of it remains in private hands in the form of profits to the oil companies. The part that has accrued to the community, however, has been transferred to the GPFG [The Government Pension Fund, Global or Statens Pensjonsfond Utland], or the “oil fund” as it is commonly known. As we can see in Figure 3, the value of this fund has increased every year until 2017, both in terms of number of kroner and as a percent of GDP. We can also see that the fund began relatively modestly in 1996, and has since seen formidable growth, even in the middle of the financial crisis which began in 2008. The fund is now growing as much from returns on investments as it is from new receipts from petroleum activity in Norway (which are declining, but still large).

The GPFG is the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund. In 2017 the value increased to over 1 billion dollars USD (equivalent to 8,488 billion NOK in Figure 3) (NBIM, 2017), and the investments amount to approximately 1.3% of total investment in all the world’s listed companies (Moses and Letnes, 2017a, p.135). Before the Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), it was estimated that the government’s total net cash flow from the petroleum industry would be approximately 238 billion NOK in 2019, increasing to 245 billion NOK in 2020 (OED, 2020).

Alternatives to Oil

In this part we compare and contrast resource management in three relevant sectors in the emerging fields of bio-economy and renewable energy: aquaculture, wind- and water-power, and bioprospecting. We wish to investigate to what degree the practices and principles of the petroleum resource management regime have been transferred to these sectors. In each sector we therefore consider:

a) forms of licensing/concessions

b) applicable means to tax the sector, and

c) potential resource rents (in 2018)

What we find is that the “new” natural resources are being managed in a manner different from the old ones, and that the new regimes do not aim to capture (nor even acknowledge the existence of) the resource rents that can arise as a result of the manner in which access to the natural resources are regulated. While the resource rents in some of these sectors are relatively modest (or even non-existent) as of today, they may grow and become significant in the future (which is what happened with petroleum).

Renewable Energy

Hydro-power has traditionally been an important source of renewable energy in Norway, while wind power both on land and offshore are still emerging. Norway’s licensing system in hydro-power was developed in the first years after the country’s independence from Sweden, and was originally designed to limit foreign ownership over Norwegian waterfalls, but quickly developed into an important method for ensuring public control over, and effective use over, resources. The most unique aspect of this licensing system was “hjemfallsretten,” the right of restitution, which built on the recognition that the Norwegian people give private individuals access to use natural resources (through a license) for a limited time period, and that “ownership” of the waterfalls and means of production should return to the state after e.g. 60 to 80 years [15].

In other words, private companies received permission to set up the necessary structures and equipment (such as dams and power stations) around waterfalls, but these would be turned over to the state in good condition once the license expires. There was an expectation that the companies would have good opportunities to cover their costs of investment over the course of the license period, in addition to securing a reasonable return on invested capital. This right of restitution ensured that the state could update the licensing terms in line with the varying resource rents, and eventually periodic updates to the terms of the license also ensured better technology and environmental protections. This general framework remains in place for regulating hydro-power production, even if the regulations have become more complex [16].

[15] For more on the development of the Norwegian power regime, see Thue (2003).

[16] Small hydro-power plants must seek a license in accordance with the Water Resources Act. Larger hydro-power plants (over 40 GWh) receive licenses in accordance with the Watercourse Regulation Act. Procurement of larger waterfalls requires a license under the Waterfall Rights Act. Electrical installations such as wind turbines, hydro-power generators, transformer stations and power lines all require a license in accordance with the Energy Act (NOU 2019: 16, p.33).

After a court challenge from the EFTA’s overseeing agency (ESA), the right of restitution for hydro-power has fallen away, but it has been replaced by an even stronger requirement for public ownership over these installations and resources. [TRANSLATOR’S NOTE: Norway is not part of the European Union, but is a member of the EFTA (the European Free Trade Association). Norway’s relationship to the EU is governed by the European Economic Agreement (EØS in Norwegian), between EFTA and EU member states]. In the legal process and following legislation, the Norwegian government clarified that public ownership of natural resources (especially petroleum and hydro-power) remains a central part of Norway’s resource management strategy. In response to changes in the Norwegian regulatory framework, which are necessitated by the ESA-challenge, the Storting [Norwegian Parliament]’s Energy- and Business committee highlighted:

The majority places emphasizes that resource politics, resource management, and public ownership of natural resources are not affected by the EØS-agreement, neither the petroleum nor the hydro-power sector, and that the main lines of the current licensing policy can be maintained (Energi- og industrikomiteen [Energy and Industry committee], 1992, p.6)

Today’s licensing awards are therefore still based on the Industrial Act of 1917 (NVE, 2010), and:

The basic gist of the law from 1917 is that a license is required from the authorities in order to acquire waterfalls or power plants. Furthermore, the law is based on a founding principle that hydropower resources are the property of the community, and therefore in principle ought to be publicly owned. To the extent private interests are given access to acquire waterfalls or power plants after section 2 of the Act, in these cases the law only allows the authorities to grant time-limited licenses with conditions of restitution to the state at the end of the licensing period. In this sense, the purpose of the law since the beginning has been to secure future public ownership. (OED, 2008, p. 13, emphasis ours)

Even if the concessions for wind power production are given by the same authorities (Norwegian Watercourse and Energy Directorate, or NVE) and deals with many of the same problems, the underlying licenses can still be very different. First of all, time limits are still used for wind power licenses, typically 25-30 years (NVE, 2019c). In wind power, “the area must be returned to the original state of nature as much as is possible” (NVE, 2019c) when the license period expires. The technical installations are not required to be returned to the state (in good condition), as with the restitution rules for hydro-power, but when the “tenancy” expires after the end of the licensing period, the installations must be removed and the area where the installations stand must be returned to the public sector “in good condition” (even if it is still too early to know how this will actually play out in practice). In addition, the regimes are different in that they use differing tax rules, and there is no explicit recognition of who actually owns the underlying wind-resource, even if the energy that is produced stems from wind, wind being a natural resource from the commons in the same way as waterfalls.

Licenses in wind power are chiefly regulated by two laws: the Energy Act (1990, no. 50) and the Planning and Building Act (2008, no. 71). The aim of the Energy Act is to “ensure that the production, transformation, transmission, turnover, distribution, and use of energy take place in a socially rational way, hereunder with regard to both public and private interests that are affected” (§ 2). In this law we find the legal basis for the state to grant licenses through a process dominated by NVE and the Oil-and Energy Department (OED) (Fauchald, 2018, p.1). The other legal basis concerns the planning of land use via the Planning and Building Act, which has as an explicit goal, “promoting sustainable development for the good of the individual, the community, and future generations”, to “coordinate national, regional, and municipal tasks and provide a basis for decisions about use and protection of resources”, along with “ensuring openness, predictability, and participation for all affected interests and authorities” (§ 1-1). None of these laws discuss or even recognize that the wind/air are a public resource, owned by the people. The resource is just there – apparently freely available for exploitation.

In other words, the authorities are chiefly concerned with making sure the licenses are awarded in a fair, safe, and “socially rational” way, in accordance with local laws and regulations, through which to minimize the danger of conflicts of interests (Saglie et al, 2020). In order to accomplish this, the authorities have subsidized wind power development via a certificate system. There is apparently a wish to encourage the production of renewable energy to cover society’s energy demand (and to provide exports), and an implicit recognition that the licenses can produce local revenues and jobs–but the idea that those who own the particular resource (the wind) should get back (a part of) the resource rents, is completely absent from the NVE report on “Licensing of Wind Power Development” (NVE, 2019b).

The rules for taxation of wind power are also very different from those that apply to hydro-power (and petroleum). In hydro-power there is an explicit understanding that the resource is owned by the people, and the taxation regime is designed to capture (the eventual) resource rent (see Table 1). Hydro-power is currently subject to a number of specific taxes which stem from the fact that the industry makes use of a natural resource from the commons. In addition to the usual corporation tax, an additional resource rent tax of 37% of net income is imposed, a licensing fee that is based on hydro-power’s maximum capacity, and a natural resource tax based on the amount of power produced. Furthermore, hydro-power plants must sell up to ten percent of maximum capacity at a reduced price to the municipalities they are located in, and the property tax includes–unlike in most other industries–a tax on production equipment (NOU 2019: 16, p. 10, 50, 60, 70, and 72) [17].

When it comes to wind-power, however, there is no recognition of public ownership in the underlying resource, and the resulting tax regime has no means of collecting all or even part of the resource rents if and when they should arise. Additionally, the tax burden on wind power is much lighter: it is not subject to special natural resource taxes, licensing powers, or licensing costs. Wind power companies pay only one corporate (income) tax, and a local property tax where applicable (NOU 2019: 16, p. 147). Nevertheless, this tax regime can be changed in the future as the public committee that looked at the taxation of hydro-power recommended that the government consider introducing a tax on the resource rents generated in wind power (NOU: 2019:16, p.155) [18].

[17] In 2018, a public committee was appointed to review the current tax regime for the hydro-power industry. The committee recommends (in NOU 2019:16, p. 154-55) to abolish the license fee and the sale of power at a reduced rate to counties, as well as removing the property tax on production equipment, as they believe these types of taxes can lead to lower investments in new production capacity. They further recommend keeping the natural resource tax, and increasing the tax on resource rents by two percent, to 39 percent of net income.

[18] It bears mentioning that the industry and the wind power municipalities prefer a natural resource tax rather than a resource rent tax. As with the taxation of aquaculture, there is controversy over the question of whether the tax revenue should go to the local or the national authorities. See LNVK (2018). In general, a resource rent tax should be profit-dependent, while a natural resource tax is profit-independent.

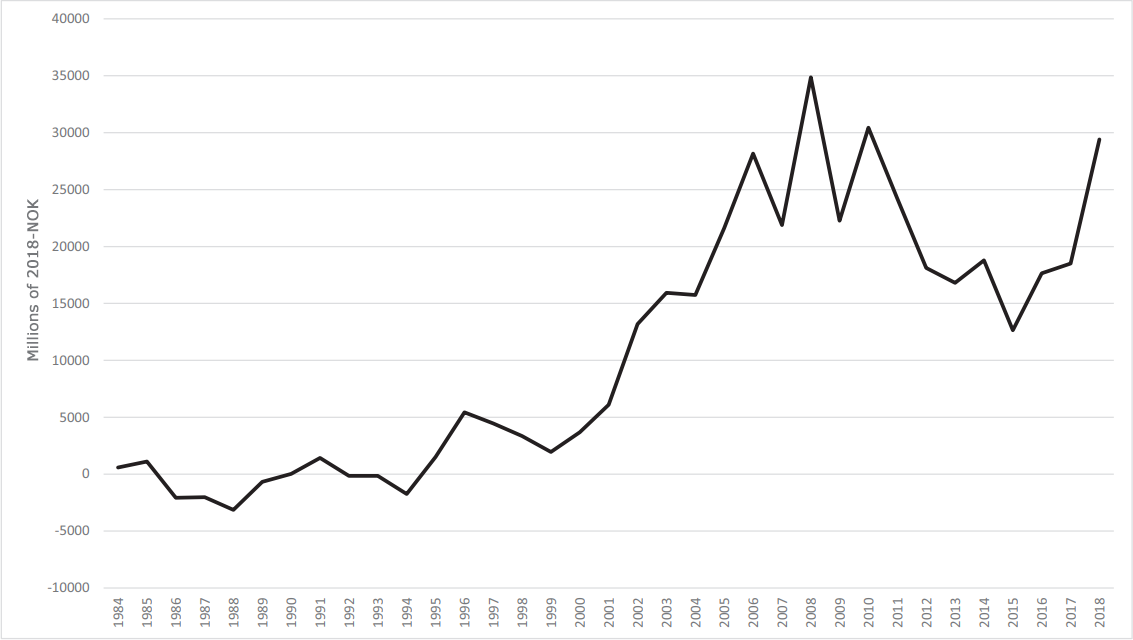

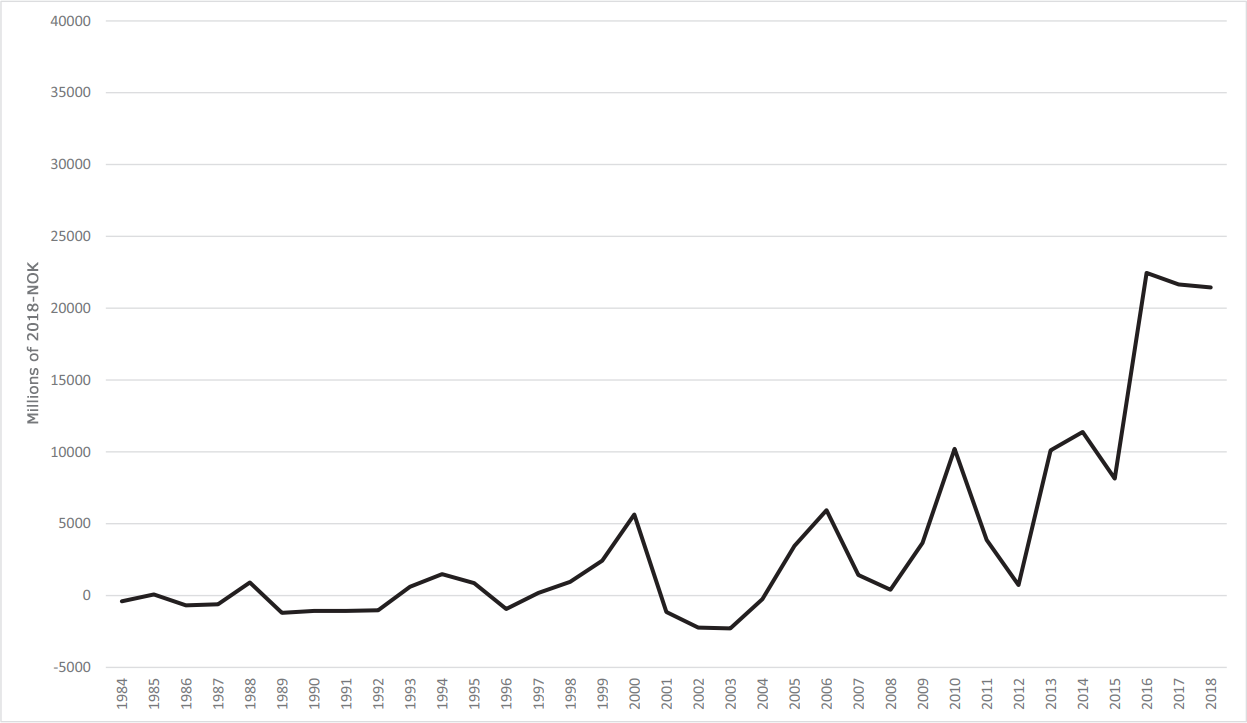

Even if the management regime for wind- and hydro-power are quite different, the resource rents from these renewable resources can be high. As we see in figure 4, the resource rents from hydro- and wind-power vary considerably over time, such that in some years there is zero or even negative resource rents (e.g. 1988 and 1994), while in other years (when energy prices are very high) they can be significant (whether it comes from wind or from water). When we look at these two sources of energy together, we see that highest resource rent to date was 30 billion NOK in 2018 [19].

The electrical power that comes from wind and waterfalls is in demand, and this makes them valuable resources, but it is the state’s issuance of (time-limited) licenses that creates the resource rent. In hydro-power most of these resources and resource rents remain in public hands due to Norway’s long-standing licensing regime. When it comes to wind, however, a large portion of the licenses are granted to companies with significant foreign ownership interests, and regardless of the resource rents generated by the licensing process, these remain in the hands of private companies [20].

[19] Figure 4 is reproduced from the data in the appendices of Greaker and Lindholt (2019), who are the first to estimate a measure of resource rents in the power sector that only includes wind and hydro-power (combined). “Previous SSB-studies of resource rents have published figures for the whole group ‘electricity-, gas-, and hot water supply’, but this is the first study that has separated power production (hydro-power and wind power)” (ibid., p.3). More specifically, they take basic value for hydro- and wind-power and deduct costs related to wages, capital, etc. See Greaker and Lindholt (2019) for details. It is not possible to distinguish between resource rents from hydro-power and from wind power in this figure, and we have also not been able to find any studies where this separation has been conducted.

[20] 93.3% of Norwegian hydro-power production is owned by the public (NOU 2019:16, p.32). In the wind power sector, by contrast, a majority of production (56.5%) lies in private hands, and 49.2% of the private share is owned by foreigners (NOU 2019:16, p.33).

Aquaculture

In Norway there are many places that are particularly suitable for fish farming, and several official reports boast of our unique conditions for aquaculture:

Norway has natural advantages for farming salmon and trout in the sea, and Norway is the world’s greatest producer and exporter of Atlantic salmon (Finance Department 2018b)

and

There are only a few places in the world where sea temperatures, currents, and more enable the efficient production of salmon at sea. Chile is the next largest producing nation, followed by Great Britain (NFD, 2015, p. 24)

These favorable conditions are found in Norwegian fjords and along the Norwegian coast, and are owned by the people and the community.

Fish farming is not open to just anyone. Permission for this is given by the Norwegian authorities, following input from a number of different government agencies. Compared with the other sectors the process is fairly easy, and it is described by the Directorate of Fisheries (2017a) as being “two-stepped”[21]. In the first step the directorate decides which applications are qualified to receive licenses. This step does not include permission to actually farm. Then comes the next step, where a number of government agencies headed by the county municipality makes the actual decision about locations, and which companies will receive access [22]. The resulting license gives a limit on production, measured in the form of the maximum permitted biomass (MPB) at two levels: the company level and the site level (NFD, 2015, p.29-30). In contrast to the licenses for petroleum and power production, there is no time limit on these licenses. Furthermore, a few are awarded at market price via auction (where pre-approved actors may participate), but most of them are awarded in a “neutral way” through a lottery system (see FKD, 2005, p.34). There is little recognition of public ownership over either the underlying resource, or the resource rent generated by the licensing process [23].

From figure 5 we can see that a significant resource rent has been created in aquaculture in the past few years. Because the government does not tax this resource rent, it remains in the hands of private individuals and companies, instead of being returned back to the authorities that have facilitated these extraordinary profits by restricting access to the exploitation of the underlying natural resource, and ultimately to the society who actually owns it [24]. Today, the aquaculture industry pays only an ordinary corporation tax on profits, even though so-called “floating farms” can fall under the local (municipal) property tax. They also pay a “market fee” and a “research fee” when the fish or the fish products are exported, but there is currently no attempt to collect any part of the resource rent.

[22] Actual commercial actors send an application to the Fishery Directorate’s regional office; these are afterwards sent out for closer handling and commentary by a number of agencies (The County Governor, the Norwegian Food Safety Authority, the Norwegian Coastal Administration, the County and NVE) and on the basis of this feedback, the application is either approved or rejected.

[23] The current system requires that existing license holders pay an application fee, while new applicants are included in an auction for licenses. Prior to 2002 the licenses were awarded free of charge, but from 2002 to 2012 the applicants had to pay “a relatively modest fee” (Ministry of Finance, 2018b). After 2016, it was decided that the tax revenues from the aquaculture industry should be distributed to counties and municipalities via the Aquaculture Fund. Of these funds 87.5% goes to the municipalities and 12.5% to the counties. Before 2016 the counties’ share was lower, and before 2013 nothing went to the municipality nor to the county.

[24] “Thus, the ground rent from aquaculture has mainly accrued to the owners of aquaculture permits. Over time the ownership in aquaculture licenses have been concentrated in fewer, larger, companies” (NOU 2019:18, p.9) and further: “Several companies have also a significant element of international funds on the owners’ side. The majority of the circa 100 Norwegian fish farming companies are, however, companies with majority Norwegian ownership with a few main shareholders. About 50 percent of the total production capacity is owned by four companies, which in turn are dominated by four ownership environments” (NOU 2019:18, p.10).

Bioprospecting

Bioprospecting can be defined as intentional and systematic exploration for components, bio-active compounds, or genes in organisms. The purpose is to discover components that can be used in products or processes with commercial or socially beneficial value, for example in medicine, food, or animal feed, as well as bio-fuel, oil and gas (FKD, 2009, p.8, 13). Bio-prospecting is an important building block of the new bio-economy that is now starting to emerge as the future’s alternative to today’s petroleum-based economy.

Norway is considered to have large and relatively unique biological resources, especially in marine regions in the north. While much of the bioprospecting until now has taken place in the temperate and tropical regions, we are now seeing a shift in focus over to biological components that can be found in cold, northern areas. Furthermore, especially high expectations are attached to both marine resources and to resources that can be found in undersea oil reserves in the north. The Norwegian government wishes therefore to focus on marine bioprospecting to lay the foundation for business development in the marine sector (especially in the northern regions) and a viable national economy “after oil” (FKD, 2009, p.14, 8).

The government sees marine bioprospecting as a central area for developing Norway in the direction of an important nation in bio-economy and a means of developing knowledge-based jobs related to the traditional sectors like aquaculture, agriculture, and forestry (FKD, 2009, p.14)

The management regime in bio-prospecting differs considerably from those in petroleum, hydro- and wind-power, as well as aquaculture, in that the Norwegian authorities are focusing on making the natural resources used in bio-prospecting as easily accessible as possible, for as many as possible. The only thing that is demanded of private actors who want to harvest biological material, is that they report this activity to the Directorate of Fisheries. The most significant part of this is that the authorities finance a system for harvesting, describing, and to some extent screening, of the biological organisms, and that the results are stored in public bio-banks. Norwegian and foreign researchers can thereafter access these descriptions virtually free of charge, in order to try to find scientific evidence for a desired effect. This entails relatively large costs for the public sector regarding, for example, research vessels, analysts, laboratory equipment, public education of researchers, etc. By providing the information free of charge to commercial actors, the authorities actually subsidize the industry, and the virtually free access can be seen as a form of non-monetary benefit sharing [25], with parallels to the “local content” policy which ensured the development of the Norwegian petroleum industry. Instead of introducing monetary benefit sharing by affirming the community’s ownership of the resource and obtaining a resource rent (as with petroleum), the authorities focus only on facilitating (subsidizing) value creation where all profits – including any resource rent – accrue to private business actors.

[25] This is a reference to the “benefit-sharing” mandates in the Convention on Biological Diversity (1994).

It was not a given that Norway would follow this management regime for bio-prospecting. Both the Biodiversity Act and the Marine Resources Act (both from 2009) confirm that genetic material from nature is a natural resource that belongs to the community at large and should be managed by the state (just like oil, waterfalls, wind, or coastal waters), and further emphasis is put on there being a rational and fair distribution of the benefits from the use of such material (KDF, 2009, p. 17). Furthermore, two very different “bio-prospecting regulations” have been sent out for consultation over the last six years. The first, which came in 2013, focused on the community’s ownership of biological resources, and provided for the taxation of any resource rent. After many critical inputs in the consultation round, there came a new proposal for regulations in 2017, where the desire for resource rent taxation had been completely abandoned. In this draft no spotlight is put on public ownership of the underlying natural resources (which is in line with the state of wind and aquaculture), but it is offered freely for private use. In hindsight the work on such a regulation has been put on ice, and the authorities are following an “open access”-line for the bio-prospecting industry.

It looks like the authorities think of this relatively new industry as a regular commercial industry, and not as one that belongs in the natural resource sector. Instead of emphasizing that the biological material (the underlying resource that is exploited via bioprospecting) belongs to the community, the government believes that “Commercialization of research results related to marine bio-prospecting does not differ significantly from commercialization of other research results. The breadth of market opportunities for the marine bioprospecting makes it appropriate to use general [regulatory] tools on the commercialization side” (FKD, 2009, p.8).

There are a number of characteristics of the bio-prospecting industry that may explain why the authorities, instead of restricting access to the natural resource through licenses and concessions, instead attempt to give as many people as possible access to it by subsidizing the harvesting, description, and (parts of) the analysis. First, only a few specimens of a species are required in order to describe the relevant compounds, enzymes, and genes that it contains. Once this description is available, the component can be reproduced synthetically, which is to say that one does not need further natural specimens in order to mass produce the gene or the enzyme. There is therefore neither a concern that the industry will deplete a limited resource (as in the petroleum industry) or degrade the environment through the extraction of the resource (as in hydro- and wind-power and aquaculture). Furthermore, no “monopoly” is created as a foundation for extraordinary profit by the authorities giving access to the resource only to a relatively small number of actors, while other actors are locked out. On the contrary, access to the resource is subsidized so that as many as possible will have access to it. In addition, the technology develops within the industry in such a way as to complicate both the collection of an eventual resource rent as well as the legal basis for sharing out the benefit (among other things, challenges regarding the digital description of the biological materials, traceability given that genes are one of many input factors, and foreign patents).

A challenge with this management regime is that the subsidization of bio-prospecting often does not lead to industrial jobs or income in Norway, because the lucrative research results are patented and sold to foreign companies that generate income and profits outside of the country. Once again, potentially great values are created through monopoly power, but the monopoly is created by patents based on the extraction of a common resource, and not by restricting access to the underlying resource. Since the market for products and processes built from bio-prospecting often are global, these patents are filed in the countries with the largest markets, and not where the original resource was found. In such cases the “people”, who own the original source of inspiration (nature), lose control of the subsequent usage of it, along with any resource rent.

As with wind power there is little recognition of the potential for resource rent. nature is made freely available for utilization in the hope that it will create jobs and revenue, while much of the income goes abroad. There is no target for resource rents here, because it arises as a result of patent rights, which are often registered abroad. Any resulting resource rent is privatized, and it is the Norwegian and foreign authorities’ issuance of patents that creates the monopoly, while the resource itself, which is the basis for the patent, is offered free of charge with no preconditions.

Conclusion

Norway’s current wealth is built on a management regime tradition that explicitly recognizes the public ownership and control over our natural resources and ensures that the resource rents they produce are returned to the community. When Norway tries to move to an economy based on biological resources and renewable energy, we could expect that these well-proven traditions will lay a foundation for the country’s future management of these resources. It is remarkable that this does not seem to be the case. It seems that today’s politicians and officials do not see natural resources as part of the community’s inheritance, but as a mere means of production that can almost be given away.

Of the natural resources we have discussed in this article, it is only in hydro-power and petroleum that the authorities have explicit control over the public resource, and therefore the ability to collect resource rents. There is surprisingly great variation in the way private actors gain access to use the various natural resources that are owned by the community. One would expect a more consistent approach that protects the public interest–as the resource management regime for petroleum does.

We are not aware of any calculations of resource rents in the field of bio-prospecting. This is a sensational fact in itself. When it comes to the other resources, the current resource rents in hydro- and wind-power and aquaculture are modest when compared to petroleum (see Figure 6). We can add that these ground rents may become considerably higher in the future as the bio-economy replaces the petroleum economy both nationally and globally.

The challenge is that the current management regimes do not give us the opportunity to ensure that the people will get a share of these resource rents (and future resource rents, if, when, and where they should arise). Instead private actors receive licenses that give them a disproportionately large return on their investments.

If Norway were to introduce consistent regimes inspired by hydro-power and petroleum, it would first have to recognize public ownership and establish a management regime that can capture the resource rent when it arises. When resource rents are secured, one can discuss how they should be shared out politically, economically, and geographically.

This is relatively easy with wind-power and aquaculture, but political will is lacking. Bio-prospecting is a more challenge case, so the authorities here must follow two parallel tracks. The first is to search for solutions for how the resource rent from the exploitation of our common biological building blocks can be returned to the Norwegian people. This may, for example, concern stricter requirements for registration when harvesting from nature and withdrawals from public bio-banks, and forming contracts that contain an obligation for the sharing of monetary benefits, and routines for tracking the path from biological inspiration to finished product (through description, screening, patenting, and commercialization). If this should be shown to be too complicated to handle in practice, it would become even more important to ensure that more of the bio-prospecting value chain (and revenue) remains domestic. This tracking would entail an expansion of the so-called “local content” policy such that in addition to encouraging Norwegian research and development in the early stages of industry, it would include to a much greater degree measures that contribute to Norwegian ownership, production, and commercialization of the results of bio-prospecting. In this way, the community can at least get some of the value creation that is based on our resources, through jobs and ordinary personal and corporate taxes.

We would like to thank Eirik Magnus Fuglestad, Espen Moe, Anders Skonhoft, and to anonymous colleagues for helpful comments.

Bibliography

Anderson; J. (1859 [1777]). An Inquiry into the Corn Laws; with a view to the New Corn-Bill Proposed for Scotland. London: Lord Overstone. Convention on Biological Diversity. (1994).

Convention on Biological Diversity: Texts and Annexes. Geneva: Interim Secretariat for the Convention on Biological Diversity, Geneva Executive.

Bogner, A., Littig, B. and Menz, W. (2009). Interviewing Experts. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Brox, O. (1987). Hvordan ivaretas grunnrenten i primærnæringene? NBIR-notat 1987: 101. Norsk Institutt for By- og Regionforskning.

Deloitte. (2014). Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative: Cash Flows from the Petroleum Industry in Norway 2013. Oppdatert desember 2014. Online at: http://www.eiti.no/files/2015/02/ 2014_EITI_rapport_engelsk_for_2013.pdf

Edigheji, O., El-Rufai, N., Busar, O. and Moses, J. (2012). In the National Interest: A Critical Review of the Petroleum Industry Bill 2012. Review No. 1. July. Abuja: Centre for Africa’s Progress and Prosperity.

Energi og industrikomiteen. (1992). Innstilling fra energi- og industrikomiteen om endringer i energilovgivningen som følge av EØS-avtalen. 28 oktober (Innst. O. nr. 17. (1992-93); Ot.prp. nr. 82 for 1991-92). Oslo.

Fauchald, O.K. (2018). Konsesjonsprosessen for vindkraftutbygginger – juridiske rammer. Report 1/2018. Lysaker: Fridtjof Nansens Institutt.

Fiskeridirektoratet. (2017a). Tildelingsprosessen. Oppdatert 24. april. Online at: https://www. fiskeridir.no/Akvakultur/Tildeling-og-tillatelser/Tildelingsprosessen.

Fiskeridirektoratet. (2017b). Forskrift 16 januar 2017 nr. 61 om produksjonsområder for akvakultur av matfisk i sjø av laks, ørret og regnbueørret.

Finansdepartementet. (2018a). Skatter, avgifter og toll 2019. (Prop. 1LS). Online at: https:/www. regjeringen.no/no/dokumeter/prop.-1-ls-20182019/id2613834/

Finansdepartementet. (2018b). Mandat for utvalg som skal vurdere beskatningen av havbruk. Oppdatert 7. september. Oslo: Finansdepartementet. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/dep/ fin/pressemeldinger/2018/utvalg-skal-vurdere-beskatningen-av-havbruk/mandat-for-utvalgsom-skal-vurdere-beskatningen-av-havbruk/id2610382/.

FKD [Fiskeri- og kystdepartementet]. (2005). Om lov om akvakultur (akvakulturloven) (Ot.prp. nr. 61(2004–2005). Oslo: Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet.

FKD. (2009). Marin bioprospektering – en kilde til ny og bærekraftig verdiskaping. Nasjonal strategi 2009. Rapport utarbeidet i samarbeid mellom Fiskeri- og kystdepartementet, Kunnskapsdepartementet, Nærings- og handelsdepartementet, Utenriksdepartementet i tett dialog med Miljøverndepartementet. Oslo: Fiskeri- og kystdepartementet.

George, H. (1886). Fremskridt og Fattigdom: en Undersøgelse af Årsagerne til de industrielle Kriser og Fattigdommens Vækst midt under den voksende Rigdom. Oversatt av Viggo Ullman. Kristiania: Huseby.

George, H. (1982 [1893]). The Condition of Labour in The Land Question and Related Writings. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation.

Giles, R. (2017). The Theory of Charges for Nature. How Georgism became Geoism. Redfern, NSW, Australia: The Association for Good Government.

Greaker, M. and Lindholt, M. (2019). Grunnrenten i norsk akvakultur og kraftproduksjon fra 1984 til 2018. SSB Rapport 2019/34. Online at: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/ 207ae51e0f6a44b6b65a2cec192105ed/no/sved/1.pdf.

Kristiansen, B.S. and Wiederstrøm, G. (2019, 12. november). Suksess for lakselobbyen. Klassekampen, s.10-11.

LNVK. (2018). Skatteutvalget vil også vurdere skatt på vindkraft. 28 November. Medlemsorganisasjonen for Norges vindkraftkommuner. Online at: https://lnvk.no/2018/11/28/ skatteutvalget-vil-ogsa-vurdere-skatt-pa-vindkraft/

Marx, K. (1981 [1865]). Capital. Volume 3. Translated (to English) by David Fernbach. Introduction by Ernest Mandel. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Meuser, M. and Nagel, U. (2009). The Expert Interview and Changes in Knowledge Production. In Bogner et al. (Ed.), Interviewing Experts (s. 17-42). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Moses, J. (2010). Foiling the Resource Curse: Wealth, Equality, Oil and the Norwegian State.» I O. Edigheji (Ed.), Constructing a Democratic Developmental State in South Africa: Potentials and Challenges (s.126-145). Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Moses, J. (2020). A Sovereign Wealth Fund: Norway’s Government Pension Fund, Global. Forthcoming in E. Okpanachi og R. Tremblay (Eds.), The Political Economy of Natural Resource Funds. Palgrave Macmillan.

Moses, J. and Letnes, B. (2017a). Managing Resource Abundance and Wealth. The Norwegian Experience. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moses, J. and Letnes, B. (2017b). Breaking Brent: Norway’s response to the recent oil price shock. Journal of World Energy Law and Business, 10, 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1093/jwelb/jwx004

NBIM. (2017, 19. September). A Trillion Dollar Fund. Online at: https://www.nbim.no/en/the-fund/ news-list/2017/a-trillion-dollar-fund/?_t_id=1B2M2Y8AsgTpgAmY7PhCfg%3d%3d&_t_q= trillion+dollar&_t_tags=language%3aen%2csiteid%3ace059ee7-d71a-4942-9cdcdb39a172f561&_t_ip=66.165.1.186&_t_hit.id=Nbim_Public_Models_Pages_NewsItemPage/_ 7ea5e620-5eae-4ec3-a8d8-5ad4de19973e_en-GB&_t_hit.pos=1.

NFD [Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet]. (2015). Forutsigbar og miljømessig bærekraftig vekst i norsk lakse- og ørretoppdrett (Meld. St. 16 (2014-2015)). Online at: https://www.regjeringen.no/ no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-16-2014-2015/id2401865/.

NFD [Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet]. (2016). Kjente ressurser—uante muligheter. Regjeringens bioøkonomistrategi. Oslo: Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet.

NFD. (2017). Forslag til forskrift om uttak og utnytting av genetisk materiale (bioprospekteringsforskriften). Høringsfrist 3.okt 2017. Oslo: Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet. Online at: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/61c7cb809a7b4df3891df59b45e45fbb/ horingsnotat-med-forskrift-og-merknader.pdf.

NOU 2019:16. (2019). Skattlegging av vannkraftverk. Oslo: Finansdepartementet.

NOU 2019:18. (2019). Skattlegging av havbruksvirksomhet. Oslo: Finansdepartementet.

NVE [Noregs vassdrags- og energidirektorat]. 2010. «Konsesjonshandsaming av vasskraftsaker. Rettleiar for utarbeiding av meldingar, konsekvensutgreiingar og søknader». Veileder 3/2010. http://publikasjoner.nve.no/veileder/2010/veileder2010_03.pdf.

NVE. (2019a). Større vannkraftsaker. Oppdatert 23. april. Online at: https://www.nve.no/ konsesjonssaker/konsesjonsbehandling-av-vannkraft/storre-vannkraftsaker/.

NVE. (2019b). Konsesjonsbehandling av vindkraftutbygging. Oppdatert 23. april. Online at: https://www.nve.no/konsesjonssaker/konsesjonsbehandling-av-vindkraftutbygging/?ref= mainmenu.

NVE. (2019c). Trinn 6 – Oppfølging av innvilget konsesjon. Oppdatert 28. november. Online at: https://www.nve.no/konsesjonssaker/konsesjonsbehandling-av-vindkraftutbygging/trinn-6- oppfolging-av-innvilget-konsesjon/. O’Donnell, E.T. (2015). Henry George and the Crisis of Inequality. New York: Columbia University Press.

OED. [Olje- og energidepartementet]. (2008). Om lov om endringer i lov 14. desember 1917 nr. 16 om erverv av vannfall, bergverk og annen fast eiendom m.v. (industrikonsesjonsloven) og i lov 14. desember 1917 nr. 17 om vassdragsreguleringer (vassdragsreguleringsloven) (Ot.prp. nr. 61 (2007-2008)). Oslo: Det Kongelige Olje- og Energidepartementet.

OED. (2011). En næring for framtida – om petroleumsvirksomheten. En næring for framtida – om petroleumsvirksomheten (Meld. St. 28 (2010 – 2011)). Oslo: Olje- og Energidepartementet. Online at: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/19da7cee551741b28edae71cc9aae287/no/ pdfs/stm201020110028000dddpdfs.pdf

OED. (2019). Petroleumsskatt. Norsk Petroleum. Oppdatert 7. oktober. Online at: https://www. norskpetroleum.no/okonomi/petroleumsskatt/.

OED. (2020). Statens Inntekter. Norsk Petroleum. Oppdatert 7. februar. Online at: https://www. norskpetroleum.no/okonomi/statens-inntekter/.

Pereira, E., Spencer, R. and Moses, J. (Ed.) (2021). Experiences of Managing Wealth, CSR and Local Content Policy: Sustainable Development of Extractive Resources Industries. Sveits: Springer International.

Ricardo, D. (1817). The Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo, Vol. 1: Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. Online Library of Liberty. Online at: https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/ ricardo-the-works-and-correspondence-of-david-ricardo-11-vols-sraffa-ed.

Saglie, I.-L., Inderberg, T.H. and Rognstad, H. (2020). What shapes municipalities’ perceptions of fairness in windpower developments? Local Environment, 25(2), 147-61. DOI: 10.1080/13549839.2020.1712342 Senior, N. (1850). Political Economy. Third Edition. London og Glasgow: Richard Griffin and Company.

Skonhoft, A. (2020). Lønnsomhet og rente i oppdrettsnæringen. Samfunnsøkonomen, 1, 12-14. Online at: https://samfunnsokonomene.no/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Samfunnsokonomennr.-1.pdf Thue, L. (2003). For egen kraft: kraftkommunene og det norske kraftregimet 1887-2003. Oslo: Abstrakt.

UN General Assembly. (1962). UN Resolution on Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources. Online at: http://legal.un.org/avl/ha/ga_1803/ga_1803.html

UN General Assembly. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI) of 16 December 1966 entry into force 23 March 1976, in accordance with Article 49. Online at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CCPR.aspx.

Van Audenhove, L. (2007). Expert interviews and interview techniques for policy analysis. Vrije University, Brussel. 9. mai utkast. Online at: https://www.ies.be/files/060313%20Interviews_ VanAudenhove.pdf.

Vormedal, I., Larsen, M.L. and Flåm, K.H. (2019). Grønn vekst i blå næring? Miljørettet innovasjon i norsk lakseoppdrett. FNI Report 3/2019. Fridtjof Nansens Institutt. Wiederstrøm, G. (2019, 1. november). Vil skatte storfiskane. Klassekampen, s. 12.