A smart conspiracy theorist never wears a tinfoil hat. According to research done by MIT students in 2005, tinfoil can actually amplify mobile communication and satellite frequencies, including those used by the Federal Communication Commission. Based on these findings, the researchers (jokingly) speculated that tinfoil hats were a ploy propagated by the government to track the thoughts of U.S. citizens.

So remove the headgear, but stay frosty: There are conspiracies happening around you all the time, and thanks to evolution, you probably have suspicions about dozens of them—even in the face of logic and reason. Conspiracies are fun to dissect and debate, but there's a deeper appeal: Humans have a natural skepticism toward authority and power.

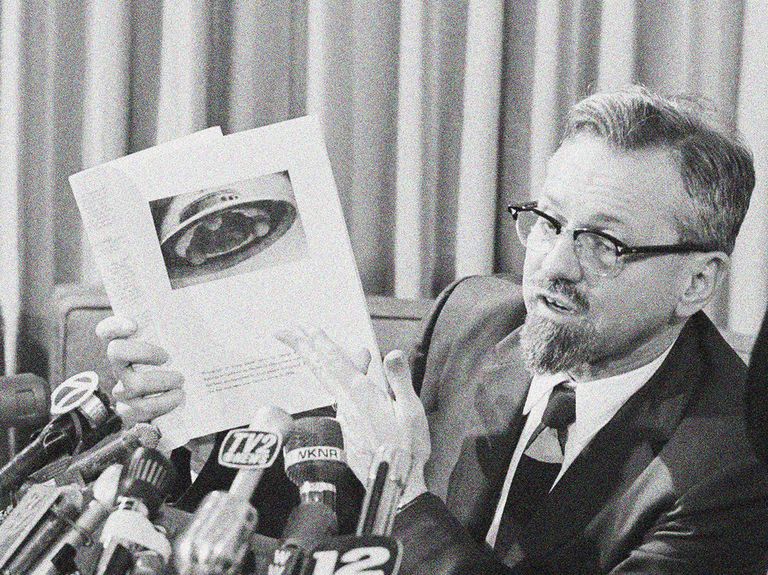

“We descended from primates that tended to notice dangerous, hidden things, like a predator in the grass,” says Dr. Michael Shermer, presidential fellow at Chapman University and bestselling author of Why People Believe Weird Things and The Believing Brain. “Our ancestors were the paranoid ones who assumed the worst and survived.”

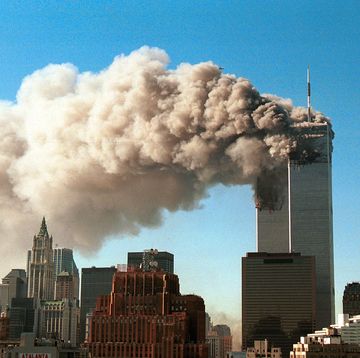

According to Shermer, a conspiracy theory concerns: a) two or more people, b) plotting in secret, c) to gain an immoral/illegal advantage over someone else, d) without that party’s knowledge. This definition includes outrageous conspiracy theories—Stanley Kubrick’s staged moon landing, Tupac Shakur’s fake death—but it also contains things like Watergate, Pearl Harbor, and the coordinated terrorist attacks on 9/11. Whether rooted in a Wikipedia deep dive or documented history, however, most conspiracy theories are hard to prove, which is part of what makes them alluring—and dangerous.

Conspiracy theories give us just enough facts to entertain our whispering, primitive, ancestral fears. But instead of a hungry sabretooth tiger working against our well-being, the modern danger might be the government, a powerful corporation, or—in the ugliest conspiracy theories—an entire ethnic group. We still look for danger in the grass, even in places that seem safe.

More people believe in conspiracy theories than you might expect. Over 50 percent of people—regardless of age, educational level, or political preference—believe the JFK assassination was the work of more than one person, according to a 2017 poll. A 2019 survey indicated 45 percent of American adults have doubts about the safety of vaccinations, while Gallup reports 68 percent of Americans believe the government is hiding information regarding UFOs. A 2016 Chapman University survey found most respondents believed the government is covering up information regarding 9/11, while an alarming 33 percent believed the government is concealing information about the legendary “North Dakota crash,” an incident you don’t remember because the researchers made it up.

There are swaths of evidence against all these theories (apart from the North Dakota crash), but a few wild-seeming conspiracies have been proven, or at least justified. The Roswell, New Mexico “weather balloon crash” of 1947 was a cover-up (just not of a flying saucer), and the U.S. government has admitted to investigating the existence of UFOs for years. In the 1930s, the government let 399 black men in Tuskegee, Alabama go untreated for syphilis so scientists could study the deceased. With that in mind, it’s not surprising that in 2005, 1 in 7 African Americans surveyed by the RAND Corporation and Oregon State University said they believed AIDS was created by the government to control the black population.

There have been legitimate threats by the Powers That Be before, so it makes sense why we’d be wary of continued threats now. This doesn’t excuse theories like the existence of shape-shifting lizard-aliens disguised as humans (something 4 percent of Americans believe and 7 percent aren’t sure about, according to a Public Policy Polling Survey), but it demonstrates the strange logic that persists behind our suspicions.

A thought experiment: You’re up for a promotion at work. It’s down to you and one other candidate. You’re sitting at your desk and you look up to see a coworker you clash with leaving your boss’s office. A couple of minutes later, your boss says you’re being passed over for the promotion. Did your coworker conspire to sabotage you?

Feeling stressed or conflicted over the promotion makes you more likely to believe your antagonistic colleague has it in for you, according to a study from the University of Texas and Northwestern University. That’s because in stressful, ambivalent situations, the human brain is inclined toward simplicity. That means you’d prefer to face down one spiteful coworker instead of the myriad questions that arise from your failure to secure the position: Are you good at your current job? Did you do something to offend your boss? Are you even in the right line of work? Your brain wants to eliminate those complications, so it poses an attractive alternative: Your co-worker screwed you over.

Classic conspiracy theories like the fake moon landing or the 9/11 inside job are more complex versions of this phenomenon. The official 9/11 narrative says a small group of radical terrorists felt such hatred for Americans they weaponized one of the country’s most common forms of transportation against an unprepared government. This is horrifying, and it raises difficult questions like: Can our government keep us safe? Could this happen again? Is American foreign policy causing more harm than good?

Against that ambiguity, it’s easier to handle the prospect of an inside job: There’s one clear enemy (the Deep State) and one clear response (resist!).

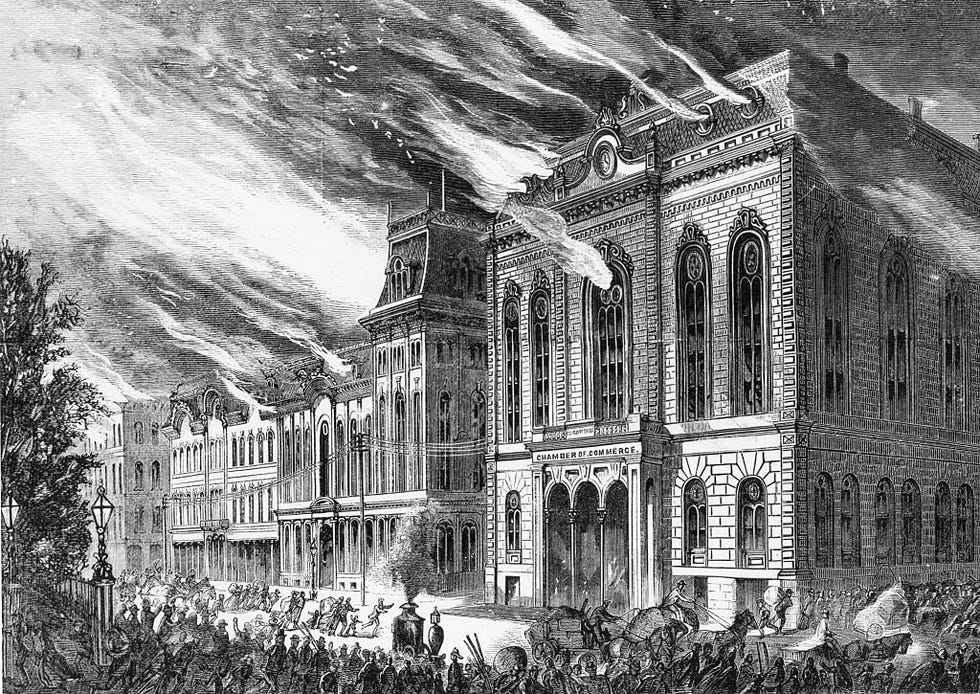

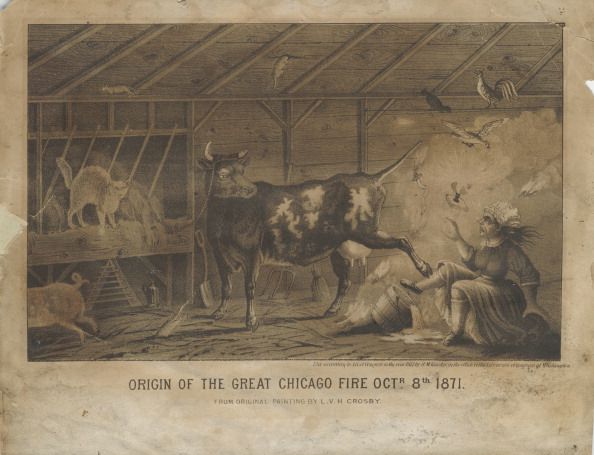

On Sunday, October 8, 1861, the Great Chicago Fire destroyed $200 million in property, killed 30 people, and left approximately 100,000 people homeless. To this day no one knows what caused the blaze, but at the time, a rumor spread that Catherine O’Leary, an Irish immigrant whose home had been spared, started the fire herself. An inquiry into O’Leary from the Board of Police and Fire Commissioners came up inconclusive, but the lack of an alternate explanation only fueled the rumors of arson. The Chicago Times reportedly described O’Leary as a villain, a “hag [who] swore she would be revenged on a city that would deny her a bit of wood or a pound of bacon.”

The truth behind the fire’s devastation is probably more nuanced. Chicago had gone months without rain at the time, and in those days, most homes in the city were made of wood, making them particularly flammable. After the fire started, reports indicate firefighters were sent to the wrong location. As the responders were delayed, 30 mile-per-hour winds created “convection whirls”—collisions between overheated air pockets and cooler surrounding air—that carried the flames and spread burning debris throughout the city. Chicagoans had the choice: believe their city was destroyed by happenstance, or at the hands of Catherine O’Leary. The immigrant never stood a chance.

In addition to xenophobia, O’Leary fell victim to “proportionality bias,” the logical fallacy that believes the cause of an event should feel as important as its impact. Proportionality bias lies behind many of the most popular conspiracy theories. For instance, it feels disproportionate that JFK, the so-called most powerful man in the world, could have been assassinated by one disturbed individual, or that Princess Diana,—a powerful, famous, real-world princess—was killed in a car accident.

“When the outcome of an event is significant, momentous, or profound in some way, we are inclined to think it must have been caused by something correspondingly significant, momentous, or profound,” says Rob Brotherton, PhD, author of Suspicious Minds: Why We Believe Conspiracy Theories. “Simply, we reckon big things have big causes.”

Proportionality bias is hard-wired into the human brain because proportional cause and effect is a core principle of nearly every action and reaction we face each day. This relates to Isaac Newton's third law, and it creates expectations for how the world works. If you hit your thumb with a hammer you might have to apply a bandage, but not amputate the digit. That’s a disproportionate effect. When the world defies those expectations, and random embers burn down a third of Chicago or lone individuals devastate a nation, we look for a conspiracy rather than the truth.

Faith in American institutions is low. The 2019 Edelman Trust Barometer Poll found only 48 percent of Americans trust the media, and just 19 percent believe “the system”—a combination of government, the media, businesses, and nongovernmental organizations—is "capable of solving our country's challenges." In the past, conspiratorial thinking has seemed to compound this mistrust. A 2012 survey by University of Miami associate professors Joe Uscinski and Joseph Parent found people more inclined to believe in conspiracy theories were less likely to vote, volunteer for a candidate, or run for office, though Uscinski now says the anti-establishment candidates of the 2016 election mobilized conspiracy theorists toward government participation, even if those candidates didn't alleviate any mistrust.

Conspiratorial thinking can be a logical, intelligent response to a world in which there really are institutional cover-ups and malicious actors, but conspiratorial thinking can also decay governmental participation, increase skepticism of people around us, and in the ugliest scenarios, intensify xenophobia and other modes of division. That’s how we go down the rabbit hole to a place where Osama bin Laden didn’t die in the raid at Abbottabad or the Holocaust didn’t happen.

“Once you accept one conspiracy theory, you’re more likely to tick the box for most of them, even if they contradict,” Shermer says. “People who believe Princess Diana was assassinated by a secret cabal are also more likely to believe she faked her own death. Those can’t both be true! She’s either dead or alive!”

So how do we hold on to a healthy skepticism without going too far? One way is to engage with what Shermer calls his “conspiracy protection kit,” a series of questions that help determine how likely a conspiracy theory is to be true or false. One such question: How many people would have to be involved in covering up a given conspiracy? The larger the number, the less likely the cover-up exists.

“Watergate just involved a handful of people trying to cover up the facts,” Shermer says. “But 9/11 being faked would require hundreds of thousands of operatives working in perfect harmony. There was someone controlling the flights, someone setting up explosive devices in the buildings … and after 19 years not one person involved in the inside job wants to go on 60 Minutes and talk about what they saw?”

Shermer also points to the value of negative evidence. Even though Wikileaks has released tens of thousands of incriminating documents about the American government, from happenings at Guantanamo Bay to sensitive foreign policy emails, none of these records appear to mention a 9/11 cover-up, Roswell, or Area 51. “If these things were true there should be a paper trail,” Shermer says. “The grander the conspiracy, and the less evidence there is, the less likely it is to be true.”

While Shermer’s toolbox is helpful, it’s also worth remembering that behind every conspiracy theory is an understandable, human desire for safety. We live on a planet where random embers of chance create catastrophic change, and our attempts to make sense of that can lead to truly bizarre, and sometimes harmful, beliefs.

“We’re all trying to understand the world and how it works. What binds us together is easy to take for granted,” Brotherton says. “That is a more productive place to start: We’re all in over our heads, and there’s more going on than we can possibly understand.” So behind everyone who says we’re being infiltrated by shape-shifting lizard-aliens is someone struggling with the complexity of everyday life.

Unless, of course, they’re a shape-shifting lizard-alien. Then you’re right where they want you.