In another extreme ruling, the Supreme Court has removed foundational, decades-old constitutional limits on religion in public schools. Its Monday decision in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District overruled a half-century of precedent to elevate the rights of public school officials over students. The ruling will allow these officials to engage in coercive sectarian prayer on the job. Justice Neil Gorsuch’s 6–3 decision is another maximalist attack on the separation of church and state, stripping students of their First Amendment freedom against religious indoctrination. His opinion also embraces a false narrative of faith-based persecution, illustrating yet again that this court will manipulate facts to reach its desired outcome.

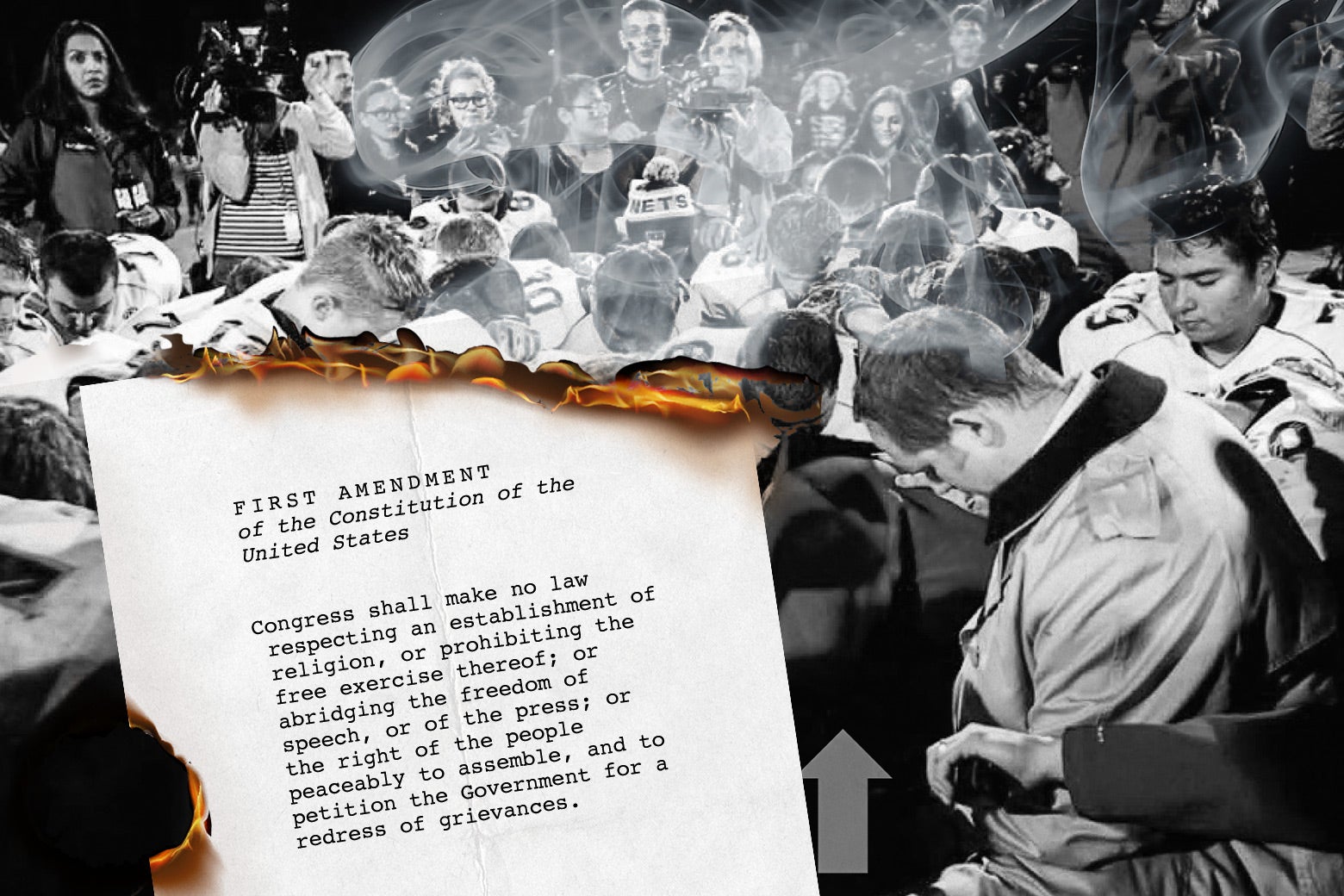

Joseph Kennedy, the plaintiff in Monday’s case, worked as a football coach at a public high school in Washington State. In 2008, he began reciting Christian prayers at the 50-yard line after games, allowing students to join him. Eventually, a majority of the team consistently formed a prayer circle with their coach. During these invocations, Kennedy would lift a helmet while kneeling students surrounded him. He also led Christian prayers in the locker room before games. In 2015, the school district learned of this practice and asked Kennedy to stop, asserting that his conduct violated the First Amendment’s establishment clause (which bars the government from “respecting an establishment of religion”). The district noted that non-Christian students could be alienated by his behavior and asked him to pray privately, or while he was off-duty.

Kennedy refused. Instead, he hired a team of far-right lawyers and fomented a media firestorm, framing himself as a martyr facing oppression from anti-Christian secularists. The coach continued to kneel in prayer after games, and even students who hadn’t played would race onto the field to join; after one game, zealous students created a “stampede” that injured several classmates. Parents informed the district that their children only joined the prayer circles for fear of being ostracized or denied playing time. Finally, exasperated school officials placed Kennedy on paid administrative leave, and when his contract expired at the end of the season, he did not reapply. He then filed a lawsuit alleging a violation of the First Amendment rights to free speech and free exercise.

Under precedent that existed until Monday, Kennedy’s lawsuit was frivolous. The Supreme Court has long held that the establishment clause outlaws the recitation of prayer in public school. It has forbidden prayer at graduation ceremonies and football games, explaining that schools must avoid “state endorsement” of religion and religious “coercion” of students. These rules derive from the “Lemon test,” which the court created in 1971 and refined in 2005. The gist is that the government violates the establishment clause when a “reasonable observer” would view its actions as endorsing religion.

For decades, conservative judges have criticized this rule as unjustifiably hostile toward religion in the public square. Now they have prevailed: In his opinion for the court, Gorsuch overruled Lemon as well as its “offshoot,” the endorsement test, wiping out dozens of precedents in one fell swoop. With remarkable mendacity, the justice actually claimed that the court had already overruled these cases, citing a series of concurrences and dissents. (He disregarded defenses of these tests as a useful gauge of a law’s purpose and effect on religion.) Gorsuch replaced the test with a novel, amorphous standard: The establishment clause, he asserted, must be interpreted with “reference to historical practices and understandings,” by asking what “the Founding Fathers” would have thought. Once again, the Supreme Court has compelled judges to become amateur historians, substituting bright-line legal standards for mushy and subjective appeals to “tradition.”

Gorsuch then declared that Bremerton School District violated Kennedy’s free speech and free exercise rights by asking him to pray privately or off-the-job. The district’s policy was not “neutral” or “generally applicable,” he wrote, because it targeted “religious speech for special disfavor.” (Not long ago, SCOTUS actually directed schools to target such speech to maintain the wall of separation between church and state.) Moreover, Gorsuch argued that the policy impermissibly suppressed Kennedy’s speech, because it was “quiet” and therefore not made “pursuant to his official duties.”

This claim requires a heroic suspension of disbelief. In 2006’s notorious Garcetti v. Ceballos, the Supreme Court’s conservatives held that government employees have no free speech rights while performing their official duties. Kennedy was obviously in the midst of his official duties when he kneeled on the field, in uniform, responsible for the conduct of his students. And when he led his prayer circles, he was not “quiet,” but loud and prominent by design. His expression was a quintessential example of on-the-job “government speech” that, according to Garcetti, falls outside the First Amendment.

To reach his conclusion, Gorsuch simply rewrote the facts. In his account, Kennedy had been suspended exclusively for his silent prayer—not the spectacle he created by hijacking football games with prayer circles. And because this prayer was allegedly so “quiet,” it qualified as “private” expression shielded by the First Amendment. The coach’s prayer, Gorsuch insisted, was “not delivered as an address to the team, but instead in his capacity as a private citizen.” So even though he was in the middle of a field that he could only access because he was performing his job responsibilities, his speech bore no imprint of government approval, and was totally unconnected to his work as a coach.

As Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in dissent, Gorsuch’s “myopic framing” contradicts precedent that requires courts to assess the “taint” of “past practice,” because “reasonable observers have reasonable memories.” To promote its preferred narrative, the court had to ignore Kennedy’s “years of inappropriately leading students in prayer in the same spot, at that same time, and in the same manner.” Sotomayor also criticized the majority’s whole repudiation of Lemon, the endorsement test, and the “reasonable observer” standard. But she pointed out that the opinion goes further than that: It also defanged the very heart of establishment clause jurisprudence, the principle that states may not coerce individuals into worship. “The coercive pressures” of Kennedy’s conduct were “obvious”; even Justice Brett Kavanaugh acknowledged during oral arguments that students might fear retaliation if they did not join. In case there was any doubt, students did come forward to attest that they felt coerced into prayer.

Gorsuch’s response to these kids? Get over it. “Learning how to tolerate” public prayer, he wrote, is just “part of learning how to live in a pluralistic society.” A “tolerant citizenry” must live with the coercion of children into a particular faith at school; so long as they are not forced to join at risk of formal retaliation, they have no right to demand the freedom from indoctrination in their schools.

The implications of this embrace of school prayer will be sweeping. Previously, the court was sensitive to the “subtle coercive pressure” that school officials exert when practicing their faith alongside their students. No longer. The establishment clause now permits this conduct; in fact, the free speech and free exercise clauses compel schools to tolerate it. After Kennedy, what remains of the 60-year bar on prayer in public schools? Can a district bar teachers from praying at the start of class and inviting (but not formally requiring) students to participate? How about a principal at the start of an assembly? School districts will likely be too fearful of a lawsuit to limit this conduct. After all, any teacher who’s told not to pray can now launch a lawsuit that may take years, and millions of dollars, to litigate—all the while turning themselves into a cause célèbre.

The roughly 5,000 students in Bremerton School District practice dozens of different faiths. Yet Gorsuch evinced no concern for the religious liberty of Muslims, Jews, Hindus, and atheists who may now be subjected to thinly veiled pressure to practice Christianity at school. These students do not matter to the Supreme Court’s conservative majority. Reading Kennedy with last week’s decision forcing Maine to fund private sectarian schools, a principle emerges: Under the guise of defending religious freedom, Christians have a First Amendment right to impose their faith on the rest of us.