"I don’t want other families to go through this," CJ's mother says. "It's too hard. It just shouldn't be like this.”

This article was made possible by the RGJ Fund and does not require a subscription. Please consider supporting Mark Robison's journalism by donating at RGJ.com/donate.

In a nearly empty hospital room on the sixth floor of Renown Regional Medical Center’s Sierra Tower over the Christmas holiday, 19-year-old CJ Stout lies curled in the fetal position.

Before his mother Shahna Stout enters, she puts up her hair, takes off her glasses and stows her phone so he can’t grab them.

She and CJ’s legal guardian, Austyn Mahon, call gently and repeatedly to wake him. It's about 11:30 a.m.

Eventually, CJ sits up, groggy, a single sheet and a thin blanket twisted around his waist. His mom and Mahon reach toward the dark red stretch marks near his armpits. They hadn’t noticed them appearing so angry before.

He’s gained about a third of his body weight in the eight months since being brought to Renown, in part due to psychiatric meds he’s on.

On the night of May 2, 2022, Reno police took CJ to the hospital after responding to a 911 call about an attack that left CJ's mother and big sister, Mechayla, bruised and bitten.

“I'm terrified of my son,” Stout said later in a second floor waiting area at Renown. “The night everything went bad back in May, I had to call the cops on my own child because he was hurting me. He was hurting me.”

Her voice is filled with anguish. She is a mother who doesn't know how to help her son.

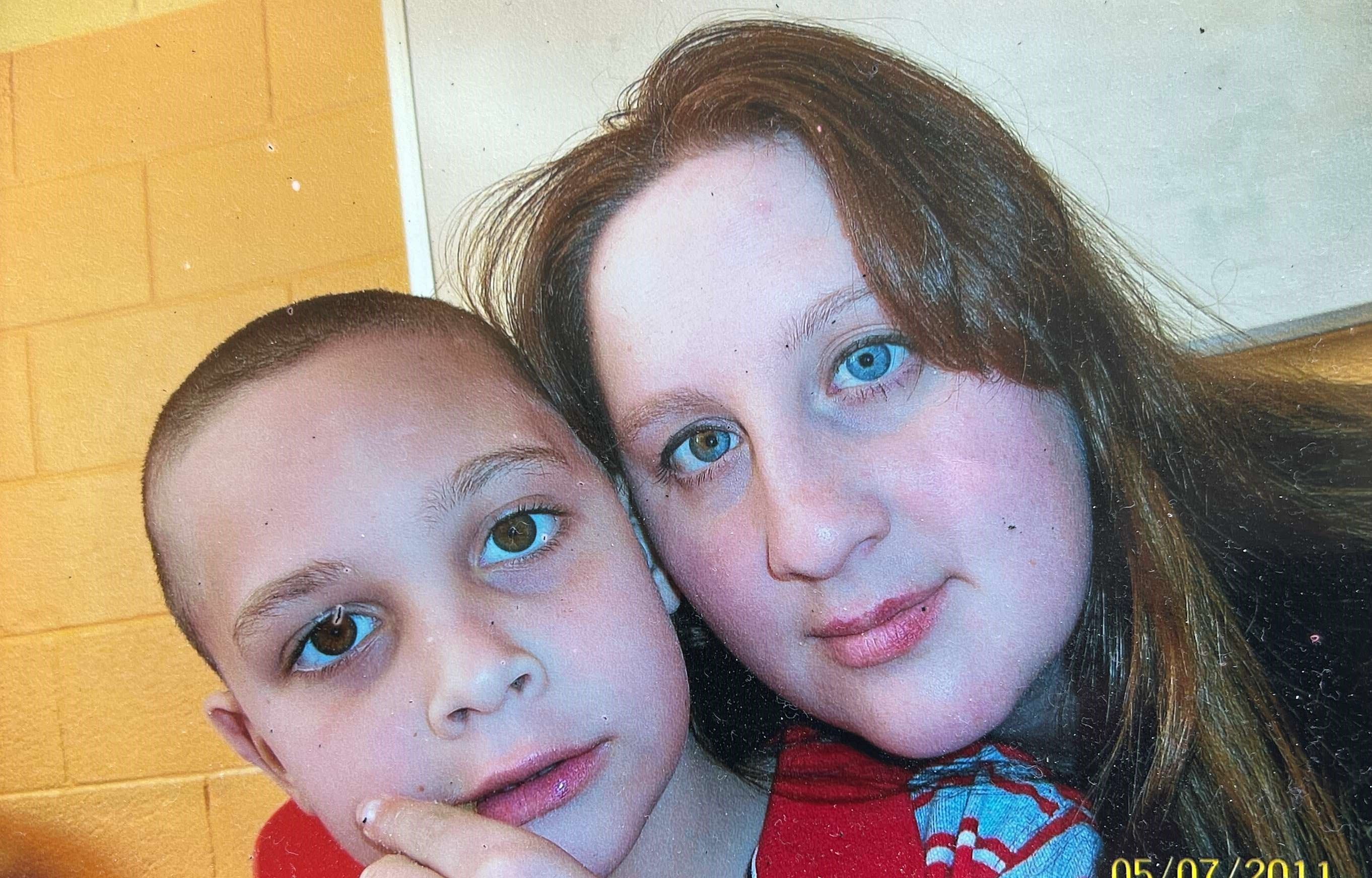

CJ has severe autism. His mental age is that of a 3-year-old, and he suffers from seizures. He also loves dinosaurs and spaceships.

Since turning 19, CJ has become more aggressive. He sometimes grabs things forcefully, including people.

Mahon and Stout suspect schizophrenia might also be an issue. It often manifests at this age – and it runs in the family. While she was being attacked, Stout said, CJ’s eyes had a strange smiling look, like he was hearing voices or seeing visions.

"Renown has said that any testing for schizophrenia would have to be done after he left the hospital," she said.

Although Renown says CJ’s behavior is improving, Mahon and CJ’s family worry he’s not getting enough social and mental stimulation and rarely leaves his room.

Signs of CJ’s agitation are all over. Smears of dried feces mark the walls, the windowsill, the window, the bathroom’s grab handles and the shower stall.

No one thinks Renown is the right long-term location, but the hurdles to reaching a good outcome for CJ are many:

- Renown is an acute-care hospital. It treats people who are sick or injured. CJ is neither, and it doesn’t have the trained staff or other resources to appropriately care for CJ, yet Renown doesn't feel it can ethically release him because he has nowhere else to go.

- The state of Nevada, which is charged with being a safety net for people like CJ, says there are “unprecedented staffing vacancies” with service providers that deliver around-the-clock care at group homes. The same situation is hitting communities across the nation. Efforts to find CJ a home anywhere – even outside Nevada – have been ongoing for months without success.

- Reno’s affordable housing shortage plays a part, too. Even when service providers can find enough staff, they often can’t find houses that would work as group homes for people with disabilities.

CJ’s court-appointed attorney, Dave Spitzer of Northern Nevada Legal Aid, calls Nevada a “resource desert” for services that help people like CJ.

“Nevada hasn't been able to attract them to our state in a way that allows people to be placed," he said, "especially in Northern Nevada."

All this means the best outcome – maybe the only outcome – will be that CJ is placed in a group home far away from the people who love him.

“Selfishly, I want services for my son, I want him to be OK – and he's not getting that here. He's not at all," Stout said of Renown. "I would love to find a good placement for him. I don’t want other families to go through this. It's too hard. It just shouldn't be like this.”

Renown not set up for patients with behavioral health needs

Renown Regional Medical Center is a Level II trauma center that receives many “social admissions” — people who aren’t sick or injured but who arrive at the hospital on Mill Street anyway.

“People generally see us as the place to go for help, so we get all manner of patients,” said Joe Macaluso, Renown’s director of risk management. His job is to make sure Renown is safe for patients and staff, to reduce injuries and lawsuits.

Macaluso said that in his eight years with Renown, he's only known of two patients, including CJ, who had a long-term stay because a placement couldn't be found.

Short-stay social admissions are a much bigger issue. Those are "where you have a person who lacks resources, lacks family, lacks the wherewithal, lacks decisional capacity, and they simply have no one or no place to go," Macaluso said.

"We see those patients probably on a daily basis, most of whom are not admitted," he said. "There's the homeless man who wants to get out of the cold so he comes in, complains of some condition. It's ruled out and we have to discharge him."

A patient like CJ who has no discharge plan is "extraordinarily rare," he said.

Macaluso meets daily as part of a team that discusses “complex discharge patients.” CJ is one of those. And he agrees with CJ’s mother that Renown is not a great place for CJ.

“He needs a special environment, which we simply don't have,” Macaluso said.

Sometimes the hospital has used “soft restraints” when CJ has acted out. It provides either a “safety sitter” or 24/7 security outside CJ’s door. He sees child-life specialists and social workers.

“We have special nurses who seem to do really well with him. We've been able to take him out to the children's healing garden,” Macaluso said.

“But it's difficult in that his behavior can be very unpredictable. So we find that some staff seem to work with him better than others. Those staff that feel intimidated – we don't schedule them to care for him. And we're consulting with as many experts as we can: psychiatrists, psychologists, (Nevada Health and Human Services) staff.

"It is a very, very, very difficult situation for everybody, including CJ and the staff.”

Money is also an issue. CJ is on Medicaid, which pays for medical care for those with low incomes. CJ's hospital stay, though, isn't for medical reasons, so there's nothing to bill Medicaid. Renown is not receiving reimbursement.

But that’s not the primary driver for wanting to find him new living arrangements, Macaluso said.

“For any patient who's in the hospital with no (acute medical care) needs, you need to move on,” he said.

Hospitals are full of sick people, and this creates dangers for long-term patients, he said. In fact, CJ contracted COVID in the hospital, and his family and guardian insist it wasn’t from them.

Some staff think CJ isn’t safe to be around either.

Three complaints have been filed by Renown staff with the Reno Police Department. Through a public records request, the RGJ viewed them.

The first one filed Nov. 27 says that a nursing supervisor was having an employee file the report about an incident a month earlier because "Renown's risk management team told her to start filing police reports for incidents with this patient due to the amount of incidents."

Two of the police reports categorize the incidents as "assault/battery," and one as a "sex crime." All three were closed by police. The reasons given for not pursuing them included that CJ's mental capacity made the officer "unable to determine probable cause to arrest him."

One of the complaints involved an administrative assistant who said that she's normally able to calm CJ down with snacks when he gets angry. But on May 20, "he reached up with both of his hands and grabbed her hair" before pulling her to the ground.

The clerk said it took six security officers to restrain CJ and get him back into his bed. According to the police report, "portions of her hair (were) ripped out as a result of this incident. She has also been attending physical therapy since this incident due to pain in her neck."

In another police report, a nursing team member said that "while checking his vitals he reached up and groped her breast. She swatted his hand and said, 'No CJ.' He reached up again and she blocked his hand. He then tried to grab her thigh and she felt his hand swipe across her pelvic region. She stepped back and he grabbed her arm and tried to pull her into the hospital bed. She was screaming for help and fighting against his grip. She was able to break free and get outside of the room. She had bruising on her upper arm where CJ had grabbed her."

The police reports contain comments that nursing staff are waiting for CJ to be accepted "into some type of high security mental health facility."

Macaluso said Renown encourages all staff to report assaults regardless of the perpetrator.

"They have a right to feel safe in the work environment and so we support them in that effort, if that's something that they want to do," he said.

He added that the hospital has teams of people – social workers, case managers, nurses, physicians, even its chief medical officer – “scouring the country looking for a place for CJ since he got to Renown.”

The possible places CJ could go have lengthy waiting lists, are expensive or both.

“Either you have to have really good insurance or a lot of money to be able to fund that kind of placement,” Macaluso said.

The bottom line: “We've been unsuccessful in getting CJ placed.”

Why doesn’t Nevada have enough services for people with severe autism?

The Nevada Department of Health and Human Services is the agency charged with helping people who need assistance, such as elderly people who can no longer care for themselves and people who have severe mental, intellectual or physical disabilities.

Its public information coordinator, Miles Terrasas, said by email that HHS “is aware the current service system is struggling to serve individuals with intensive behavioral support needs due to the complexity of the needs of the individual, staffing and available housing.”

People like CJ often have what’s called a “dual diagnosis” – two serious conditions at one time. In CJ's case, he has a dual diagnosis of autism and an intellectual disability, as mental retardation is now called.

People with a dual diagnosis who may have lived successfully in their family home faced new challenges during the pandemic, Terrasas said, and this resulted in many needing “out-of-home intensive services.”

In short, there’s more demand for the special type of group home CJ needs – yet the state is struggling to get enough of these group homes set up.

In bureaucratic parlance, the state contracts with "supported living arrangement" providers, who then work with "direct service" providers to staff these group homes.

The direct service providers are responsible for the day-to-day care of people within each home. They assist with laundry, cleaning, hygiene, shopping, medication management and socialization.

In homes with people who have complex behavioral needs like CJ, caregivers often need higher levels of training on topics such as positive behavior support, crisis intervention and working with various mental health diagnoses.

There was already traditionally high turnover among these in-home caregivers. A big reason for the inability to keep people in those jobs – besides "getting injured and wiping butts," as CJ's guardian Mahon put it – is the low pay. Average wages, Terrasas said, are $12 to $15 an hour.

Besides staffing shortages, many providers report difficulties in finding appropriate rental homes to open new 24-hour intensive supported living settings.

“The rental inventory for 3- or 4-bedroom homes is low in many Nevada communities,” Terrasas said. “Plus, the home may need other features such as a single story, varying levels of (Americans With Disabilities Act) accessibility, yard space, etc., depending on the needs of the individuals who will be residing at the home.”

There are times when the state finds an interested group-home provider, he added, but the provider can’t find a rental home to begin services.

There are 388 “Intensive Supported Living Arrangements” homes throughout Nevada, serving 1,160 people, according to state figures. Of those, 90 homes with 263 residents are in Washoe County. These group homes with intensive services generally have three to four residents each. Housing more than four requires special approval.

Getting the right mix of people in such a home is not easy, Terrasas said. For instance, it wouldn't work to place someone who exhibits physical aggression into a home with individuals who are considered medically fragile.

That is a challenge in finding placement for CJ.

As of Dec. 31, the waitlist for intensive supported living arrangement homes is:

- 8 – Reno area

- 8 – rural areas

- 157 – Las Vegas area

There are currently fewer than 10 adults who are residing in out-of-state placements because of a lack of in-state providers, Terrasas said.

October brought a bit of good news that could lead to more group homes in Nevada. The state was awarded more than $14 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds “to develop Intensive Behavioral Support Homes to better support individuals with intensive behavioral support needs in the community.”

How the hospital environment is affecting CJ

Reports of aggression by CJ at Renown make it harder for him to get placed in a group home.

Two psychologists who are assistant professors at the University of Nevada, Reno – Matthew Lewon and Bethany Contreras – say it’s not surprising CJ would act out at the hospital.

“When you have autism and communication difficulties, aggression becomes a way of communicating,” said Lewon, a board-certified behavior analyst and faculty advisor for service contracts with state agencies that help find placement for people like CJ.

“It’s a way of saying ... ‘This situation is aversive, there aren’t pleasant activities for me to do,’" Lewon said. "When you're left with that, all you can do is try to escape from it as much as you can.”

Contreras said she imagines any 19-year-old would rebel if stuck in a hospital room for months on end. And for someone with CJ’s issues, they “should be treated a little bit differently from a verbally competent adult – but it sounds like the hospital doesn’t have that training."

That lack of training has led to police reports. And police reports, Contreras said, don't help people like CJ.

“A police report isn't going to change his behavior,” she said. “There needs to be a different policy in place – and different treatment and different supports.”

The hospital is in a tough position, Lewon added, because there needs to be some recourse and help for staff who might get hurt.

Contreras mentioned the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore as the gold standard for the type of care that would benefit CJ. It treats children with a wide range of disabilities from age 6 to 21. It has a severe behavior unit and trains parents so those with aggression issues can potentially return home.

“It’s a really comprehensive, intensive model,” Contreras said. “But it requires a lot of training, a lot of facilities – and funding is a huge piece of that.”

If Renown staff had proper training in working with people who have severe behavioral issues, CJ’s aggressive outbursts might not have led to police reports or been viewed as sexual assault, Lewon said.

But because that training isn't in place – and not expected at an acute-care hospital – CJ's prospects are dimmer.

“The degree of aggression is going to be a problem in finding him a placement just because people are going to be a little bit squeamish about it,” Lowen said.

What’s next for CJ?

A single mom, Shahna Stout choked up more than once when talking about CJ, who remains in that nearly empty hospital room as the weeks roll by.

“My life was so intertwined with his that in May, when he got ripped away, I didn't even recognize what was left of me,” she said.

“After 19 years of living my life for this one person, when he was gone, it was hell. I'm still trying to figure it out almost eight months later.”

She wants what’s best for CJ, but in Northern Nevada, it’s not clear what that is.

“I still say to this day that if I had not called the cops that night, chances are somebody would have come over to check on us and found something really horrible,” she said.

“He probably would have killed me and my daughter and he would have killed our dogs because something is intrinsically wrong with him right now. And he needs help and there's nowhere to turn to.”

Mechayla Stout – inspired by the issues facing her little brother his whole life – got a degree in social work.

While interning at UNR’s Nevada Center for Excellence in Disabilities, she found that Nevada residents were having to send family members with disabilities to other states such as Utah, Arizona and California to find services “because Nevada just has nothing.”

Without a legal guardian, CJ would've been expected to go back home. If not, his mother would've been reported to Adult Protective Services for abandoning him. Putting the rest of the household's safety in danger was not an option, Shahna Stout said.

To help the family, Mahon – who was CJ’s one-on-one aide for three years – offered to become his guardian after the May 2 attack.

"I decided it would be better for someone I know to be the guardian, as I could trust Austyn to do what was in CJ's best interest, so I took him up on his offer," Stout said.

Renown wants Mahon to take in CJ. But Mahon said he doesn’t feel comfortable doing this because he's already taken in someone with issues similar to CJ's.

Due to this pressure, Mahon has filed to rescind his guardianship of CJ. A hearing is scheduled in April. If successful, Washoe County’s public guardian would become CJ’s legal guardian, one of about 270 cases it handles at any given time.

It’s not clear what difference a change in guardianship would make because there still isn’t any place for CJ to go.

With so few resources in Washoe County, Mahon hopes sharing CJ’s story might inspire the creation of a support group, a place where families can talk and feel less alone. He also wants CJ to know he's working to improve his situation.

As they hug at the end of the Christmastime visit, Mahon says, “I love you. I’m trying, OK? I'm trying.”

Mumbled words come out of CJ’s mouth, “Love you.”

Mark Robison covers local government for the Reno Gazette-Journal. His wages are 100% funded by donations and grants; if you’d like to see more stories like this one, please consider donating here. Send him your story ideas to mrobison@rgj.com.