For the last two years, we’ve all been focused on China’s wobbly economy. And all this time, China’s small neighbor Vietnam has been ever so quietly heading toward a banking crisis.

On Nov. 2, Danh Van Thanh, chairman of the nation’s eighth largest lender, Sacombank, resigned without offering a reason. Hints are surfacing in Vietnamese media, which is heavily controlled by the government, that all is not well at the institution. Last week local newspaper Tuoitre News quoted a State Bank of Vietnam official saying Sacombank was being “monitored” and that the central bank was prepared to step in and “support” the lender. In August, police arrested the former chief and co-founder of Vietnam’s Asia Commercial Bank (ACB) for breaching “state regulations on economic management,” causing a run on deposits.

Banks lent enormous sums to state-owned companies because the government told them to. Vietnam, a Communist one-party state, ditched central planning in the 1980s, then tried to create a form of state-controlled capitalism like China’s. The government decided to copy Beijing’s policy of growing large, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that dominates important industries. And starting around 2005, the Vietnamese government encouraged state-owned banks to lend monster sums to those government-backed companies, which fattened up quickly by expanding into businesses they largely did not understand.

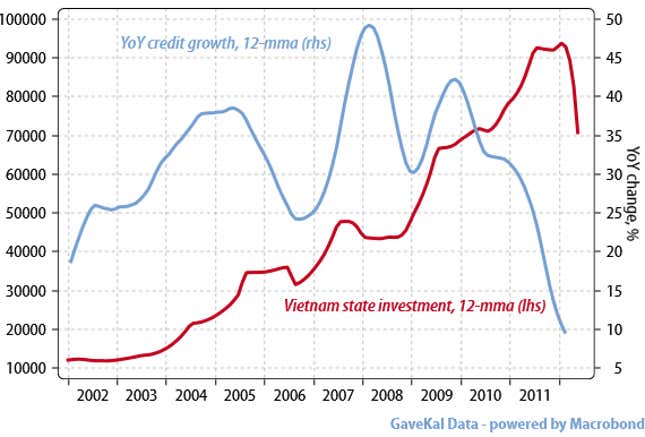

Here is a chart showing the credit explosion and fast expansion of the state-owned sector in Vietnam:

And the state-owned enterprises spent the cash on bizarre expansion plans. Vinashin, a state-owned shipbuilder, almost went bankrupt in 2010 after expanding into unrelated sectors such as finance and beer. Nine of the companies’s top officials were jailed in March for misusing state resources. Another state owned company that extended itself into unfamiliar areas was Vietnam National Shipping Lines, known as Vinalines. Its former chairman was arrested last month for alleged economic crimes. Vinalines ran up debts of over $2 billion after diversifying into industries including finance and real estate.

No one really knows the extent of the banks’s problems. Vietnam’s prime minister said today that the country was tackling its bad loans problem. The country’s central bank says bad loans are 8.82% of total assets, but Fitch Ratings says the figure is closer to 13%. Meanwhile, Gavin Bowring, South East Asia analyst at economics consultancy GaveKal, told me that when he visited Vietnam in June and interviewed bankers and fund managers, “the median estimate people gave me for bad loans was around 20% of total loans.” Standard & Poor’s, which has not estimated the exact level of bad debts, wrote in a late September note that it expects Vietnam’s non-performing loans to increase over the next two years.

Vietnamese lenders themselves do not provide much clarity. The banking industry, on aggregate, says bad loans are just 4.5% of the total, according to S&P, but Vietnam’s accounting standards are rather generous on that score. Under Vietnamese standards, as soon as a banking manager restructures a bad loan, perhaps by agreeing to new terms with the borrower, it can be classified as current instead of non-performing. So Vietnamese banks can flatter the figure by refinancing borrowers who are not paying them back, confirms an analyst who follows these lenders but asked not be quoted on the “sensitive” topic of bad debt classification.

But Vietnamese banks do not really have foreign debt, so their troubles are not creating shockwaves in world credit markets. The Vietnamese lenders are not heading towards a major loan or bond default that would disrupt international credit markets, says Ivan Tan, who tracks South East Asian Banks for S&P. “Vietnamese banks do not really have foreign creditors,” he told me. “There is only one Vietnamese bank that has issued foreign currency bonds offshore.”

It is uncertain how the Vietnamese government will bail out its banks. For now, the Hanoi administration is pursuing what Tan calls a “private sector solution where banks consolidate, with stronger institutions acquiring those with weaker balance sheets.” Hanoi could also do what China did in the late 1990s to bail out its lenders: buy bad loans from the banks, then park them in so-called “asset management companies” that do not really have a chance of recovering much cash.

Vietnam’s international creditors do not appear concerned yet. In late September, Moody’s downgraded the country’s sovereign credit rating to B2, well into junk territory, on the back of fears about a looming banking crisis. International bond investors, perhaps flush with cash from all the quantatitive easing going on in America, have not punished Vietnam too much. As Reuters Breaking Views said put it on Nov. 6:

For a country whose bonds are rated as junk, Vietnam doesn’t borrow like one: last week, yields on its 10-year U.S. dollar bonds dropped to 4.18 percent – the lowest level since they were issued in 2010. That’s just 2.5 percentage points above equivalent U.S. Treasuries. The cost of insuring Vietnam’s debt has dropped to its lowest in two years.

That is partly because Vietnam may have a bright future ahead, if the government stops mismanaging the economy. Global manufacturers are flocking there from China to take advantage of lower wages. The country has a young population and a good trade relationship with the US.

But the bank crisis is an extremely sensitive topic in Vietnam, signaling the situation may be worse than it appears. One Vietnam-based fund manager, when called by Quartz for comment on the banking sector, declined to comment because “the government is closely monitoring who talks to foreign media or analysts about the banking sector.” It is worth questioning why the Hanoi administration is feeling so sensitive. Publicly, the country’s leaders say they are taking quick and decisive action. Vietnam’s prime minister said in a press conference today: “Resolving bad debt is an urgent task which needs to be done swiftly and resolutely, but with a reasonable roadmap and tight procedures.”