Walking into the Liberty Lake library, you can tell staff have spent a lot of thought and effort trying to get children and teens excited about reading. The Young Adult section is open and inviting. One section is devoted to nonfiction for teens, and another to graphic novels. It all sits in a wide section in the back, begging to be discovered.

The section dedicated to adult books is a more traditional library stack. The shelves are taller and closer together, divided into sections covering everything from romance to science fiction, memoir to world history.

It is down one of these tall, narrow aisles off in a corner that the book Gender Queer sits, shelved at eye-level to the average grown-up, in the adult nonfiction section. A colorful sticker on the spine announces the book as a graphic (meaning illustrated, not explicit) memoir. Flipping through the pages, readers find autobiographical illustrations by the author Maia Kobabe, drawn in a soft, cartoonish art style, sketching out their personal story of coming to terms with their identity as a gender-queer person. Two panels show the main character preparing for a pap smear. Another two panels illustrate a sexual interaction between two people, although no naked body parts are depicted in those images. Of the book’s 241 pages, five depict either nudity or sexually explicit activity.

Some readers might find those five pages inappropriate, but it would be hard to make a good-faith case that the book is a work of hardcore pornography.

And yet, Gender Queer was the most challenged library book in the US in 2022, the charismatic megafauna of a nationwide push to keep books with queer themes away from children. To Liberty Lake resident Erin Zasada, it was obscene enough that she thought it should be removed from the library entirely, preventing not just children, but any other adults from checking it out. “The entire point of my complaint,” Zasada wrote, “is that there IS a book in the public library CLEARLY marketed towards children that is completely inappropriate and explicit.”

Gender Queer is marketed to adults.

Liberty Lake Library Director Jandy Humble told RANGE that Zasada’s challenge was the only one she was aware of in the library’s two-decade history. (Reached by phone Monday, Zasada declined to comment for this story.)

And while Zasada’s initial challenge, which was made in December 2021, was denied by the Liberty Lake Library Board of Trustees (BOT), and a subsequent appeal to the Liberty Lake City Council in May 2022 was also denied, it has kicked off a two-year conversation about the difference between literature and obscenity. This has, in turn, led to a struggle for control between the library board that usually decides what books to buy and the city council that funds it.

Both groups claim democracy is on their side.

A vote tonight would be the culmination of a nearly two-year power struggle over who has ultimate policy-making control over the library. Policy updates finalized by the library board in September 2022, stripped the city council of the power to review library board decisions on challenged books. This ordinance would give them that power back and more, including proactive control of collections policy to restrict or allow what books are purchased in the first place, and to give the body more control over the process for what happens when a book’s presence in the library is challenged. Right now that authority lies — as it does with most libraries in the United States — with the library’s BOT.

This is all coming to a head now because, if advocates of giving control of collections to the city council want to win, they must pass the resolution while they have a super-majority strong enough to override Liberty Lake Mayor Cris Kaminskas’ likely veto. Kaminskas already vetoed a similar resolution this past spring, and the council that supports control will lose its supermajority on January 1.

Council Member Annie Kurtz hopes to blunt what she sees as the worst aspects of the ordinance by introducing language that commits the body to preserving diversity in library material. But with a conservative supermajority – which could override a repeat mayoral veto of the ordinance – residents like Kurtz fear conservatives will use that narrow window to shut the door on a library that serves and represents all Liberty Lake residents.

‘These types of things.’

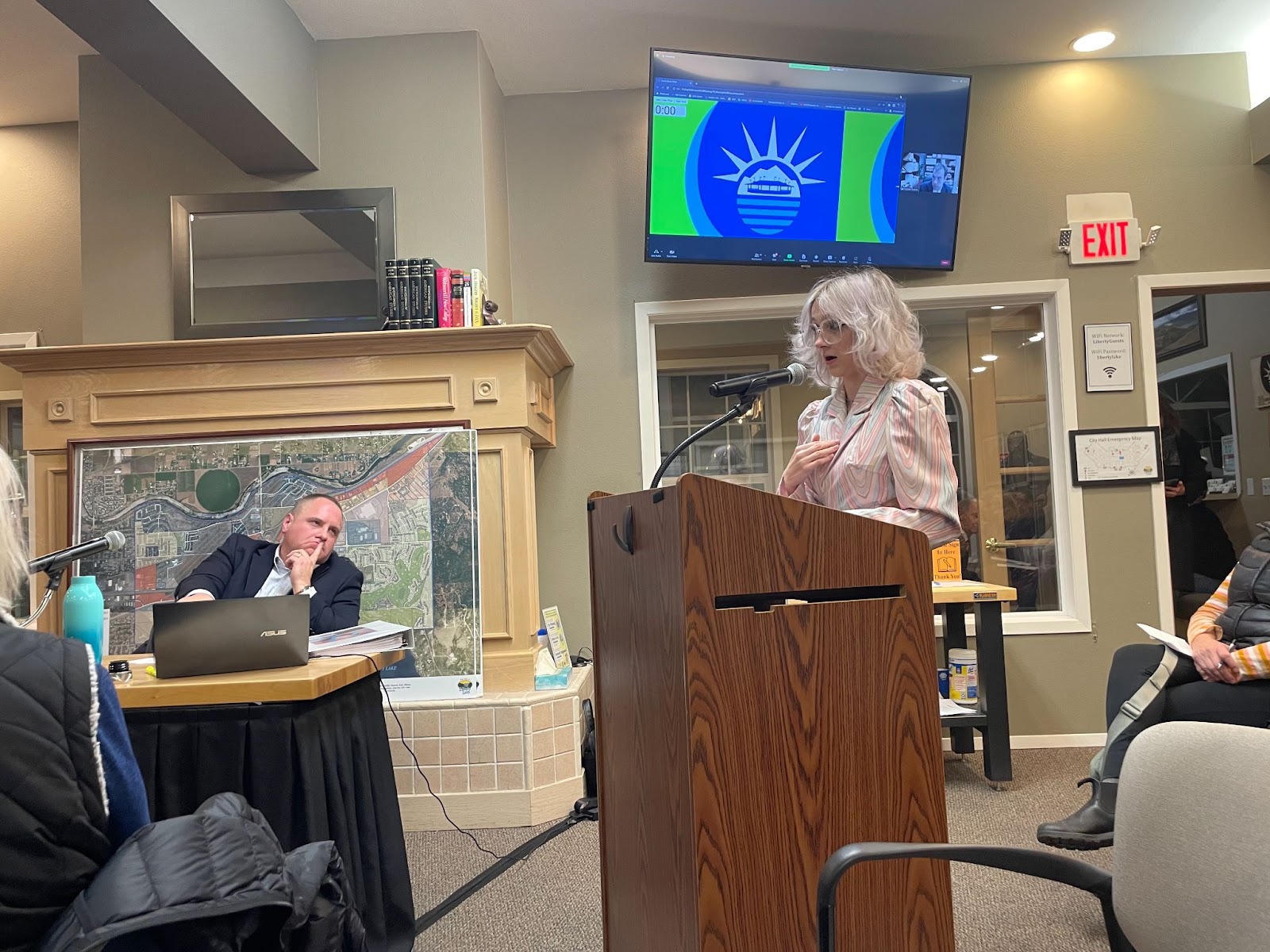

At the November 21 City Council meeting in which the new ordinance was introduced, Natalie Gauvin, a local realtor and friend of Zasada’s, was the only person to speak in favor of the ordinance. (Many written comments submitted also supported it.)

She spoke passionately, saying, “We don’t allow the library to buy Hustler. We don’t allow the library to buy X-rated movies. We don’t allow the library to buy Playboy.”

Her comment embodied an increasingly popular opinion among people proposing book bans: that books like Gender Queer fall into the same category as adult magazines — pornographic, obscene and unfit for public consumption, even among adults.

In reference to those two panels on page 167, she wrote, “There you will find two graphic pictures depicting two people engaging in oral sex…one of which is using a strap-on penis for lack of a better term. By definition, that is pornographic material and is completely inappropriate in a public library.”

Zasada wrote that even though the book was shelved in the adult section, she felt like it was marketed to children, and by trying to have it banned, she was “fighting for the kids who don’t have parents protecting them, educating them in an age-appropriate way about the pervasiveness of our country’s hyper sex-focused and ‘sexual identity culture.’”

On the original complaint form, she checked a box acknowledging that she had not read the entire book.

The book is categorized on Amazon as being for ages 18 and up and won the American Library Association’s Alex Award, which is given to books written for adults that have special appeal to young adults. If searched on Twitter or Google, the two panels on page 167 — many times censored — fill pages of results. Zasada wrote in her appeal to council members that she wanted them to spend just about five minutes with the book, paying particular attention to page 167, before deciding whether the work in its entirety “deserved to remain on the shelves of our public library.”

Whatever Zasada’s reason for not reading the entire book, websites like BookLooks.org, which USA Today described as “the go-to resource for anyone seeking to ban books – especially books about gay people or sexuality,” collate any pages, quotes or references they find to be objectionable for children, allowing parents and concerned citizens to submit book ban requests of any titles on the website without actually having read them. Though BookLooks explicitly states the website is run by “concerned parents” and are not affiliated with Moms for Liberty, they do “commonly allow these entities to use our work and accept suggestions for books to look at.”

Moms for Liberty, a conservative activist organization that the Southern Poverty Law Center has labeled an “extremist” group, recommends BookLooks on their website as a resource for parents.

The “book report” on Gender Queer published by BookLooks does cite the panels on page 167, including pictures of the offending content in its list of concerning material. It also cites quotes like “My two favorite coworkers, AJ and Fish, both out gay men,” and “Having a nonbinary or trans teacher in junior high would have meant the world to me,” in its 15-page list of inappropriate material. The review also contained a profanity counter.

Efforts like BookLooks reflect a massive and coordinated campaign in the United States by Groups like Moms for Liberty to ban queer literature, which PEN America, a nonprofit that advocates for freedom of expression said in a report last year is metastasizing across the country. Kobabe’s own website has a link of resources for communities facing a book challenge for their book, and the author penned an op-ed for the Washington Post responding to allegations that the work was pornographic.

Language used in Zasada’s challenge mirrors the national angst over literature with queer storylines: “pornographic” is the primary complaint against Gender Queer.

Reviews on BookLooks are written by a volunteer group of parents, and those reviews are not signed by the authors. Content that gets flagged as inappropriate varies. Gender Queer was rated a 4 out of 5 (5 being the most inappropriate for children) and a summary of concerns at the top of the review said the book contained “obscene sexual activities and sexual nudity; alternate gender ideologies; and profanity.”

One passage listed as inappropriate involves a character saying, “Aww, gay penguins.”

Liberty Lake Library Director Jandy Humble told RANGE libraries rely on a much more rigid and clear standard when it comes to questions of obscenity and pornography. Collections staff at Liberty Lake and most other public libraries rely on the courts: if a piece of media is found to be obscene by a judge, Humble said the library doesn’t carry it.

According to the Citizen’s Guide To U.S. Federal Law On Obscenity, produced by the US Justice Department, obscenity can be determined by using the three-pronged “Miller test”:

“1. Whether the average person, applying contemporary adult community standards, finds that the matter, taken as a whole, appeals to prurient interests (i.e., an erotic, lascivious, abnormal, unhealthy, degrading, shameful, or morbid interest in nudity, sex, or excretion);

2. Whether the average person, applying contemporary adult community standards, finds that the matter depicts or describes sexual conduct in a patently offensive way (i.e., ultimate sexual acts, normal or perverted, actual or simulated, masturbation, excretory functions, lewd exhibition of the genitals, or sado-masochistic sexual abuse); and

3. Whether a reasonable person finds that the matter, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.

In order for a piece of material to be obscene, it would have to fulfill all three criteria. All 50 states have their own obscenity laws in addition to the federal ones.

In the only extant legal ruling on Gender Queer, a Virginia court in 2022 dismissed a lawsuit that sought to have the book declared obscene under that state’s laws.

Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the director of the American Library Association’s (ALA) Office of Intellectual Freedom, said libraries are focused on closely following obscenity laws. “Librarians are aware of these laws and do not collect illegal material. They may collect materials that some find controversial for themselves or their families. But we firmly believe that the decision about materials, what young people read, should be guided by their parents.”

Proponents of the council’s control measure, though, say obscenity is beside the point.

“So long as it’s part of the city, so long as it receives about 25% of the city’s property tax revenue, there has to be oversight,” Council Member Chris Cargill told RANGE. “And there has to be accountability, and you cannot hold an unelected board accountable.”

Both sides say Tuesday’s vote is about giving “the people” control.

The people seeking control

The arguments in favor of the council taking policy control of the library are careful to avoid far-right partisan talking points, and especially the hot-button issues surrounding queer and trans visibility and critical race theory in schools or places children can access. Some of the proponents of the policy, though, have connections to groups seeking to do just that.

Zasada couched her complaint about Gender Queer as that of a single concerned parent and citizen. She was also, though, listed as a vice chair for a political action committee focused on the Central Valley School District (CVSD) called Citizens for CVSD Transparency in a 2022 Spokesman article. CVSD includes Liberty Lake schools and CVSD Transparency called itself a group of all-volunteer “conservative traditionalists who believe there is NO place in our children’s education for ‘woke culture’ or ‘political correctness.’”

The group sent a letter to district parents recruiting people wanting to fight back against “liberal, progressive sex education curriculum which panders to multiple genders, no sexual boundaries, and the abandonment of traditional morals.”

Besides her involvement with the hyper-local PAC, campaign finance disclosures show that Zasada also donated to the political campaigns of Natalie Poulson — who told RANGE she invited Mayor Woodward to hang out with Sean Feucht — and Jessica Yaeger, the head of Spokane County’s chapter of Moms for Liberty, who also appeared onstage with Feucht, Matt Shea and Woodward in August.

Cargill, one of the most vocal advocates for city council control over library policy, has spent nearly fifteen years working for conservative think tanks in the Inland Northwest, first at the Washington Policy Center (WPC). In August 2022, he became the founding president of the libertarian Mountain States Center (MSC), a think tank with the motto “Free Markets First.”

MSC is based in Idaho, but also works in Washington, Montana and Wyoming. Cargill has mostly focused on economic issues and how government is structured.

WPC focuses on free markets as well, but has used that free-market focus to engage social issues, specifically what kinds of material should appear in school libraries. In an article on its website, WPC blamed Critical Race Theory (CRT) as the reason voters in Moses Lake rejected a school levy. The think tank also hosted Christopher Rufo, one of the chief architects of the conservative strategy to attack perceived CRT and diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) policies to roll back racial- and gender-inclusive education in schools. .

These connections situate both Zasada and Cargill squarely in the center of national conversations about book banning, censorship and culture wars. In some states, governing bodies have weaponized budgets to bludgeon libraries into cutting content like Gender Queer (a playbook Cargill’s council ally Phil Folyer may have studied — in the same meeting the ordinance was discussed, he also proposed a new interpretation of property tax policy that would cut the library’s budget by over $50,000.) In Alabama, the governor pressured the state’s library service to pull out of the ALA, the organization that created the guiding principles cited in Liberty Lake library collection development policy. Under presidential hopeful, Florida governor and internet meme sensation Ron DeSantis, Florida has become the poster child for wholesale book bans under the guise of protecting children from pornography.

Democratic values vs. democratic values

Each side fighting over who controls the library says it’s angling for the best version of democracy.

The council’s conservatives and their allies believe libraries should answer directly to voters — and therefore policy decisions should be made by directly elected officials. (The library board is appointed by the council, not elected directly.)

“Look at the legislative body of the city or of the county or of the state or of the federal government: the legislative body is the policymaking body, period …. And that’s because we’re the ones who are closest to the people,” Cargill said. “We’re the ones who are elected by the people. And the people can hold us accountable. If they don’t like a policy that we adopt or we sign off on, they can go to the polls and they can vote us out of office.”

Librarians and proponents contend libraries should be insulated from political trends like the coordinated opposition to queer literature that has consumed the United States.

This specific battle over the topic of representation is relatively new. The question of control is quite old.

In 1938, the longtime American librarian Forrest Spaulding had been watching — from his perch as the director of the Des Moines Public Library — a troubling anti-democratic specter sweep across the library industry. It was happening across the Atlantic – Nazis and Communists alike were banning and burning literature inconvenient to their political goals. Around this time, people were banning and burning books in the United States, too, everything from Grapes of Wrath to Mein Kampf.

Spaulding thought this robbed people of the ability to access material they need. So he drafted a four-part values framework for library governance. The one-page document focused on his own library, declaring it would represent everyone and would be free of political whims.

And while Spaulding was writing during the fight against fascism, when far-right books were on the chopping block, that trend would reverse and intensify after WWII, with the advent of the Cold War and the Red Scare that followed.

By the 1940s, Spaulding’s view had become the prevailing sentiment among library professionals and advocates, and remains so to this day: libraries have a responsibility to shelve diverse materials, and the best way to achieve that result is self-governance.

“The library has an obligation to have resources and materials that are representative of the needs and interests of the communities they serve,” Patrick Roewe, the executive director of the Spokane County Library, told RANGE. “We don’t live in a monoculture. There are a variety of beliefs, opinions, lived experiences out there, and a library, as an entity that serves the public at large, has an obligation to have resources that reflect it.”

This stance took such hold of the library industry that the American Library Association expanded and adopted the Library Bill of Rights in 1939, and it became a font of industry statements enshrining the freedom to read and view material in public libraries. The Washington Library Association’s Intellectual Freedom Statement echoes these values and states structured their library policies based on the document.

Washington state requires library boards to be appointed by legislative bodies or be elected in their own right. But in all cases, trustees should have some level of independence over their own policymaking. The Revised Code of Washington says the “management and control of a library shall be vested in a board of either five or seven trustees.” That allows boards and librarians to bring in material that represents all groups of people, rather than only the most assertive, or politically connected ones.

Peter Bromberg, a library expert with the EveryLibrary Institute, an organization that advocates for intellectual freedom in American libraries, said this values framework mirrors constitutional safeguards against the tyranny of the majority. (Though Bromberg now works out of Salt Lake City, he told RANGE he got his start at the Spokane County Library District in 1992.)

“That’s why we have a Constitution and a Bill of Rights that lays out the areas that, regardless of what the majority of people want to do, these are the rights that are afforded to all Americans,” Bromberg said. “So it doesn’t matter if the majority says, ‘We don’t like this,’ because the Constitution says these are the areas wherein you can’t tread.”

And while questions of representative democracy lie at the heart of Cargill’s arguments for taking control of library policy, Library Director Jandy Humble offered what is perhaps the most libertarian argument for keeping things the way they are. The system as it is, Humble said, is already something like a direct democracy.

“People come in and check out the books they want to read.” If the library doesn’t have what they want, the person can ask the librarians to order it.

When the debate comes home

The particular dilemma that has manifested for the Liberty Lake City Council, according to Cargill, is two-pronged. The first prong deals with liability. Cargill worried in an interview with RANGE last week that if the library board makes a policy that inspires a lawsuit, the city would be on the hook for any political and monetary fallout.

When the trustees removed the city council’s ability to decide appeals of challenged books, Cargill believes they took away the council’s ability to defend itself in legal disputes.

But Liberty Lake City Attorney Sean Boutz expressed doubts that the old policy was adequate. Speaking to Council Member Phil Folyer during a city council meeting in 2022, Boutz said,“The policy that was in place, in my opinion, was fairly deficient … especially when it went from the board of trustees to the council.”

“There was no process,” Boutz continued. “There was nothing to advise the council what to do. There wasn’t anything as far as decision-making. It was almost as if [appealing to council] was an afterthought.” Boutz also told Folyer that the council had no authority over the trustees’ decisions.

The policy written by the library board to cut the council out of the appeals process clarified that the trustees’ decisions on book challenges would be final. The library board implemented the new book challenge policy only after consulting First Amendment case law, the city council, Boutz, the Washington State Library and the ALA, said Trustee Tom Olsen.

Humble said the library board also reviewed every public library in Washington state, and found no other library sends book challenges to a city council.

After the trustees’ report, Folyer asked to see a “red-lined” version – which would show the changes made to the policy – and a chance for the council to approve the changes. Humble, citing the city’s library code, told Folyer the board finalizes its rules independently.

“The city council doesn’t review policy updated by the library,” Humble told Folyer. “We provide you a copy with them, but it’s not something the council votes on.”

But Folyer protested: “You’re taking action away from the council in this presentation,” apparently referring to the trustees becoming the final authority on book bans.

Humble, who stood at the dais, and Trustee Shawna Deane looked surprised and vigorously shook their heads. Humble said, “No, no.” Deane, who had been sitting in the public seating section, got up and stood directly behind Humble with her hands on her hips.

Liberty Lake City Attorney Sean Boutz said in the meeting that the city council would have to change the ordinance governing the library to give itself control of such changes. “Right now, that ordinance provides the authority for the board of trustees to act and set those policies,” Boutz said.

The new policy appeared to rankle Cargill. “I don’t like being told out of the blue that the authority’s being removed,” he said in the meeting. “We’re now being told: nevermind, you don’t have any authority whatsoever, and we’ve decided to change the rules.” This led Folyer, Cargill and their allies to write the current legislation giving the council direct power over policy.

More than a year later, the trustees’ action still bothers Cargill.

“There has to be accountability, and you cannot hold an unelected board accountable,” he told RANGE last week. “Let’s say the Liberty Lake Library board now adopted some sort of discriminatory policy or some sort of policy that got the city into legal trouble. We have no recourse now. Because of the way that it’s set up, we would not be able to do anything other than remove the library board members.”

Asked if he thought the trustees were creating policy that would cause problems for the city, Cargill said nothing worried him aside from the board giving itself final authority over book challenges.

But library expert Bromberg pointed out that by trying to control the board – and potentially banning books in the future – the council is, perhaps counterintuitively, making itself more likely to be sued.

“Here’s the reality of what I see happening around the country,” Bromberg said. “When these board takeovers are happening or when city council or county governments are trying to claw back that control, they’re doing it because they want to take books off the shelf.”

This sets up an environment in which First Amendment advocates might file free expression lawsuits, and nationally, lawsuits have begun to flow.

“I’m trying to keep track of all the lawsuits that are popping up,” Bromberg said. “But, you know, all the places where these books have been pulled in violation of the First Amendment, the lawsuits are starting to catch up.”

It is not an abstract problem for Liberty Lake: as the council debated the initial attempt to control library policy this year, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Washington sent a letter to city council members saying it would “closely monitor” control of the Liberty Lake library. The ACLU has for a century filed lawsuits over book bans.

Asked if he would commit to an open library for everyone, Cargill demurred, declining to predict what might happen in the future.

“I don’t know what a future council is going to do,” he said. “I don’t know what a future library board is going to do.”

The second – and more encompassing – prong of Cargill’s concern is broader in that it strikes at the heart of the separation of powers in a representative democracy.

“The legislative branch is the one that makes the laws,” he said. “The executive enforces the laws. The judicial interprets the laws. It should never be delegated, that policymaking authority, to an unelected administrative body.”

In interviews, professional librarians and library experts challenged both the notion that city council control over library policy would better insulate the city from legal action and the notion that council control would be a more accurate reflection of democratic values.

Bromberg has worked on free-speech issues with local, state and federal libraries – said the best reflection of most state library policies, including Washington’s, is for a library to have an independent board.

“No one puts a gun to the head of the voters and says you have to have a public library,” he said. “But what Washington state law says, as many state laws say, is if you do choose to create a public library and tax yourselves to run it, you have to have a board that runs, manages and has control of the library.”

‘The library was an escape.’

At the Nov. 21 meeting, the talking points about control and property tax accountability that dominated the discourse from the council majority were largely divorced from the sentiment given during public testimony, which centered more on a desire to protect the library from censorship and foster a diversity of reading materials.

Many of the citizens who spoke in person or wrote in against the ordinance said the ordinance passing wouldn’t be a victory for democratic control, as Cargill described it, but a loss of liberty and welcoming space for queer people.

Bromberg said rhetoric about accountability for administrative parts of government was common among conservatives.

“They trot out this argument of, well, [library boards aren’t] accountable to the voters,” Bromberg said, “but a more accurate frame and the [reason] it’s set up this way initially is to create a buffer from the whims of the majority that might not be sensitive to and might be willing to take away the rights of minorities.”

An independent library, he said, is a more inclusive and welcoming place.

“With the power in the council members hands, I’m worried that they will make the library an echo chamber of their beliefs,” said Kylie Johnson, a teenager who introduced herself to every member of the council before delivering the remarks she’d prepared. “I think that everybody should have a choice to learn about what they want to believe, you know? I think they should all have a right to learn and choose their own path from there.”

Sage Warren, a 14-year-old in Liberty Lake, attended the meeting with Johnson, and told RANGE that they’d always seen the library as an escape.

“I was able to find lots of books of people who related to me,” they said. “I fear if this passes, kids won’t be able to find those same resources.

Kobabe, the author of Gender Queer, said in an interview with New York Times, “When you remove those books from the shelf or you challenge them publicly in a community, what you’re saying to any young person who identified with that narrative is, ‘We don’t want your story here.’”

With organizations like the Trevor Project estimating that between 40-50% of all queer teens consider suicide each year, at least one Liberty Lake parent made the connection between representation and mental health.

As Beth Miller, a parent in Liberty Lake, said during the November 21 meeting, “It’s a matter of life and death. It’s our role to make youth feel welcome and wanted.”

Sage Warren did not approach the podium until later in the evening. They hadn’t originally planned to speak, but felt moved to as the night went on. The notecards they’d written their comments on during the first half of the meeting shook in their hands.

“Books are not going to make your kids gay,” they said. “Don’t make the LGBTQ members of your community feel less safe because you’re afraid of a book called Gender Queer.”

A previous version of this story said a $200,000 budget cut was proposed by Cargill. The actual cut was over $50,000 and proposed by Cargill’s ally Folyer.