The app for independent voices

A moment of crises in Costa Rica

Costa Rica, the first (and so far only) country in the world that has legally abolished its army, has seen better days. The current president is Rodrigo Chaves-Robles, whose mandate began in 2022 after winning in the second round of elections.

After the pandemic hit and airports were closed, the country was severely impacted and lost one of its primary sources of revenue: tourism, which accounts for approximately 8% of the GDP. Jobs were lots, and four years later, the country still hasn’t recovered. Unemployment is at 7.0% according to the country’s census bureau (INEC). Still, informal employment (for instance, Uber drivers, who do not pay taxes or contribute to the social healthcare system) is incredibly high at 38%. The social healthcare system, affectionately known as La Caja or Cajita (“the Box”) is under considerable strain, with a low birth rate and critical infrastructure essentially falling apart. The current Chaves administration actively opposed the construction of a new hospital for the province of Cartago, allegedly because it was going to be “built on a swamp”, even if no studies proved that.

Public education, which is, for the most part, free, provides essential services (such as meals) for the poorest economic strata of the country. Yet, the current Chaves administration has gutted its budget, barely giving enough money to account for inflation. This follows the same trend as the previous Alvarado administration, which slashed the education budget while also effectively prohibiting strikes nationwide.

Security is a significant issue right now, and many would argue that it’s the most pressing one. Costa Rica used to be a country where drugs coming from South America would simply pass through the country on their way to México, Europe or the US. In recent years, however, local consumption has greatly increased, and ports are being used to distribute drugs to Europe, with notable cases involving cocaine packages stuck inside pineapples on the way to the Netherlands. Locally, there are now gangs armed with Kalashnikovs and M16S fighting for territory and carrying out targeted assassinations (sicariato) in front of schools and the general public. “Gangs”, of course, is the wrong label for these armed groups, as their members are sometimes more armed than the local police and special forces, which nonetheless manage to carry out arrests. The security situation is so dire that it’s the first concern for Costa Ricans, with unemployment being the second. And yet the current Chaves administration has also removed drug-control police forces from airports and ports, and moved a coast-guard school from Quepos, a strategic location against drug trafficking because of its position near the Pacific Ocean, to Guápiles, a place nowhere near the ocean. Recently, former security minister during the Chinchilla and Solís administrations, and magistrate, Celso Gamboa, has been arrested on charges of drug trafficking and is on his way to being extradited to the US. It is clear that for some time, officials in the highest spheres of political power and positions have been involved with drug trafficking, with many cases coming to light recently. President Chaves, however, seems more concerned with sending laws to the legislative assembly to increase working hours for Costa Ricans for less pay.

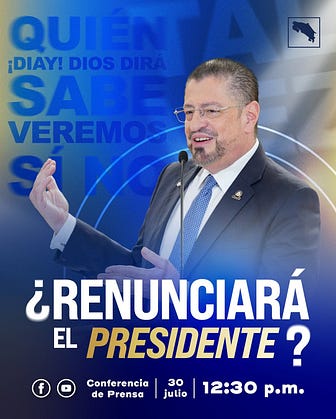

However, with all those crises, an even bigger crisis is brewing in Costa Rica. Rodrigo Chaves, the president, follows much of the style of populism brought into the world by Trump. Chaves holds weekly press conferences on Wednesdays, where he often lies or skews the truth to his convenience. He constantly blames the legislative and judicial branches for all the problems that Costa Rica is facing. He states that those branches “don’t let him work”, and yet his absence of projects presented to the legislature, or concrete actions against drug trafficking, are notable. Chaves also attacks the TSE, the country’s electoral tribunal, and for Costa Ricans, its most respected institution. It is the first time in the living memory of many Costa Ricans that there have been direct, constant attacks on other powers by the executive. After all these continuous attacks on other powers over the last three years, there’s a recent rumour, propelled initially by President Chaves himself in his weekly conferences, in which he might actually resign as the president of the country, which he can legally do by the end of July. The motivations for this are unclear, although he would run to become a member of parliament to continue having immunity against the many accusations he faces (although there’d be a nine-month period in which he wouldn’t have immunity). Chaves’ resignation might be followed by the resignations of both vice-presidents, which would mean that the president would be the head of the legislative assembly, in this case Rodrigo Arias (from the beleaguered Liberación Nacional party, a different one from Chaves). Arias is also an elderly man who has had recent bouts of bad health. This would send Costa Rica into an unprecedented constitutional crisis, akin to a self-inflicted coup, propelling the country into the abyss until the next elections, scheduled for February of next year. This incredibly irresponsible act, if it were to happen, would be an affront to people who voted for Chaves, to Costa Ricans, and to democracy. The reputational damage to the country, known to be one of the most solid democracies in Latin America, would be immeasurable and would exacerbate all the other problems mentioned before, with gangs perhaps taking advantage of the unstable political situation to expand their territories. It is a sad time in the country when all political discussion revolves around this alleged, possible self-coup instead of the urgent problems the country has been facing for a long time, which the current government has now exacerbated. I hope that these rumours, started by President Chaves himself, are just that - rumours - and that he will remain the country’s democratically elected president. It is the responsible thing to do, and Costa Ricans demand it.