The app for independent voices

Rob Reiner (March 6, 1947 to December 14, 2025) entered American living rooms not as a director, not as a tastemaker, but as an argument.

On All in the Family, he played Michael “Meathead” Stivic, the earnest, college-educated, morally certain son-in-law who stood in constant opposition to Archie Bunker’s bluster and prejudice. Meathead believed history bent toward justice if you just explained it clearly enough. Archie believed history bent toward Archie. The miracle of the show was that neither man was allowed to be simple. Reiner played Meathead with conviction and vulnerability, often losing the laugh not because he was wrong, but because righteousness without rhythm is a tough sell. In that crucible, Reiner learned something vital. Being correct is not the same as being compelling. Story wins by understanding people, not defeating them.

That lesson became the throughline of a career defined by range, empathy, and an almost mischievous refusal to be boxed in.

His directorial debut, This Is Spinal Tap, did not shout its brilliance. It whispered it, deadpan and merciless. By treating absurdity with seriousness, Reiner revealed how thin the line is between confidence and delusion. Rock stars were not mocked from above. They were observed from eye level. The joke landed because it loved its subjects just enough to let them hang themselves. That balance, affection paired with precision, would become a signature.

From there, Reiner pivoted to Stand by Me, a film so emotionally honest it still feels like a shared memory. Childhood was not romanticized. It was respected. Fear, loyalty, cruelty, and wonder all occupied the same space. The boys were not symbols. They were people on the brink of knowing too much. Reiner understood that growing up is less about finding courage than about realizing you already used it.

Then came The Princess Bride, a film that somehow managed to parody fairy tales while becoming the best one ever made. It worked because Reiner trusted sincerity. Romance was allowed to be romantic. Adventure was allowed to be joyful. Humor never undercut heart. The film spoke fluently to children and adults because it respected both. It winked without smirking. That is harder than it looks.

With When Harry Met Sally, Reiner turned his attention to adulthood and discovered that love is mostly conversation, timing, and unresolved baggage. The film succeeded because it refused fantasy. Relationships were awkward. Desire was inconvenient. People argued not to win but to survive themselves. Reiner let dialogue carry the weight, trusting that honesty, especially funny honesty, would do the work.

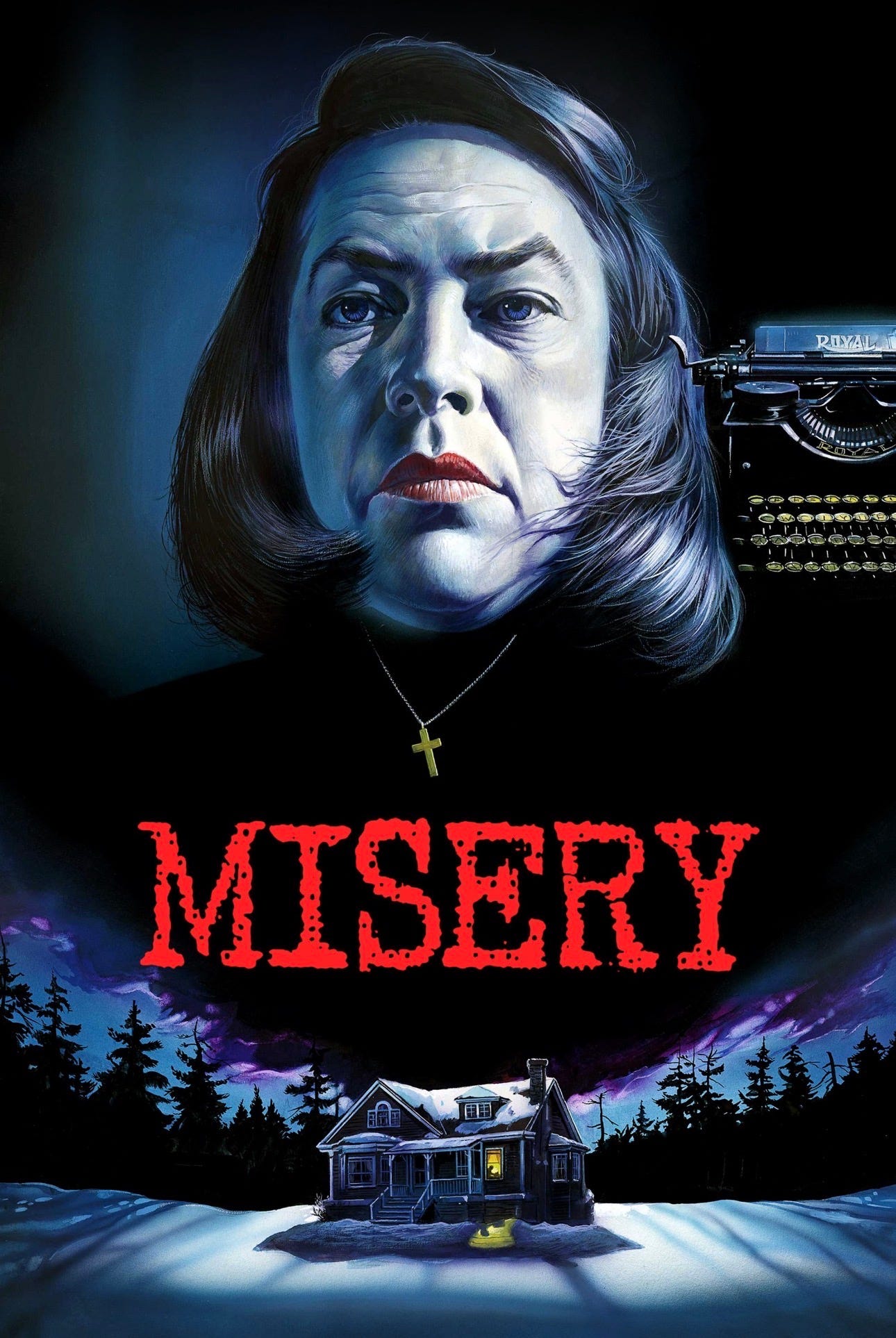

Then he shifted again. Misery stripped away warmth entirely, replacing it with intimacy of the most terrifying kind. Obsession became claustrophobic. Control became violence. The restraint of the direction made the horror unbearable in the best way. Reiner proved he did not need spectacle to generate dread. He needed focus.

Then there was A Few Good Men, a film that put power itself on trial. It asked whether authority deserves obedience and whether truth survives institutions designed to bury it. Reiner staged morality as a collision between certainty and conscience. The courtroom became a theater of belief. The famous line worked not because it was loud, but because it revealed fear beneath confidence. Another Archie moment, sharpened by decades of observation.

Looking back, the arc feels inevitable. Meathead arguing principles. Spinal Tap skewering ego. Children learning mortality. Lovers learning timing. A writer trapped by control. A soldier crushed by command. These are not disconnected works. They are chapters in a long study of how humans justify themselves, fail each other, and occasionally get it right.

Rob Reiner’s gift has never been flash. It has been clarity. He sees people as they are, not as archetypes. He believes comedy and drama come from the same place. He understands that stories last when they respect their audience enough to tell the truth with warmth.

He started as a foil to Archie Bunker. He ended up directing films that understand both Archies and Meatheads. That range is not accidental. It is earned.

And it is a lot