Netflix is not a tech company

Way back in 1992, just as the ‘Internet’ was starting to sound interesting, a company in the UK used technology to disrupt television.

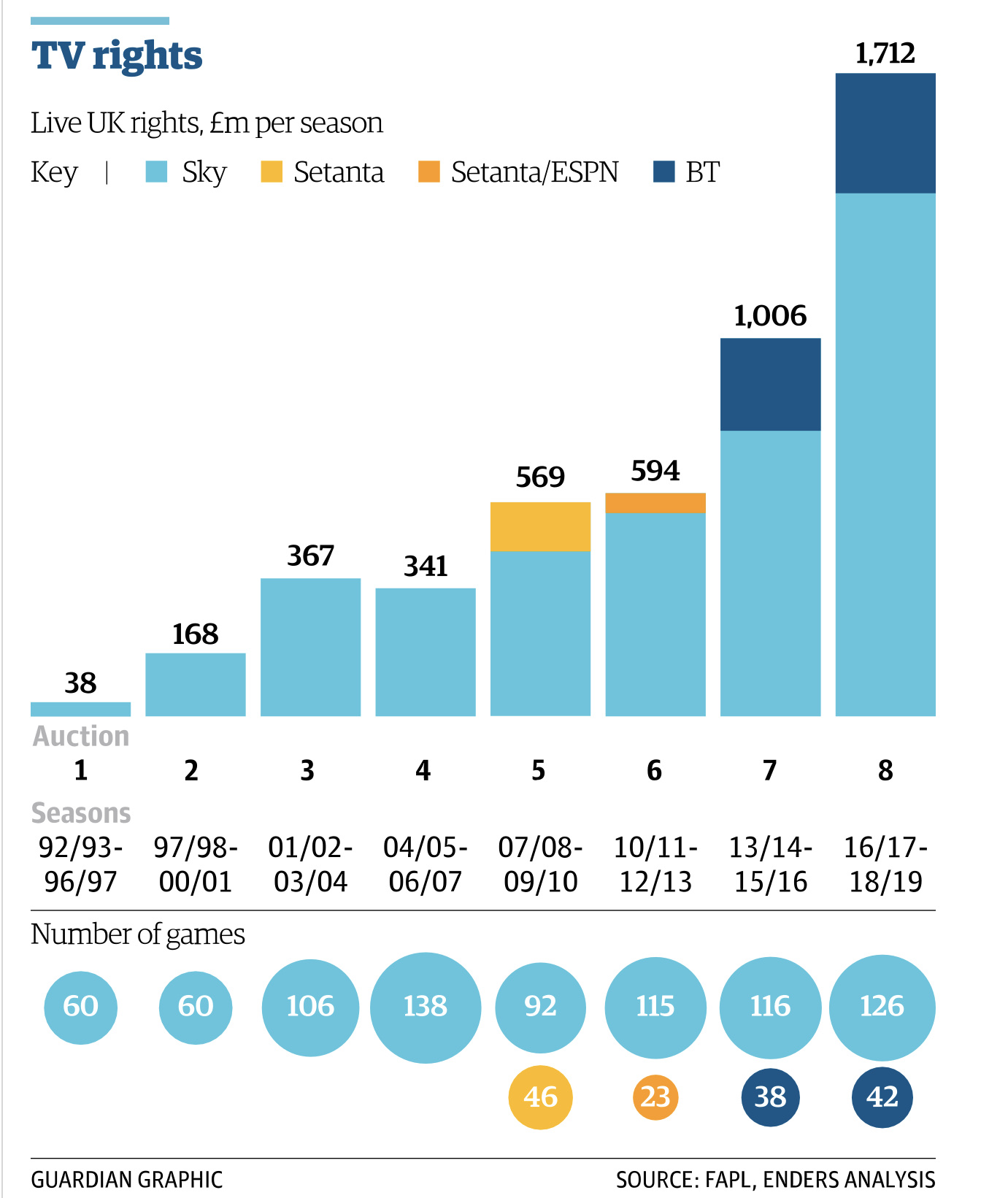

Rupert Murdoch’s Sky realised that you could buy football rights for far more than anyone had ever thought of paying before, and you could make your money back by selling the games on subscription instead of pay-per-view or advertising, and you would be able to deliver that subscription using encrypted satellite channels. This was a big deal, both for Sky and for the UK Premiership league, and it was the beginning of something much bigger.

Sky used technology as a crowbar to build a new TV business. Everything about how it executed that technology had to be good, and by and large it was. The box was good, the UI was good, the truck-rolls were good, and the customer service and experience were good. Unlike American cable subscribers, Sky subscribers in the UK are generally pretty happy with the tech. The tech has to be good - but, it’s still all about the TV. If Sky had been showing reruns of MASH and I Love Lucy no-one would have signed up. Sky used tech as a crowbar, and the crowbar had to be good, but it’s actually a TV company.

I look at Netflix in very much the same way today. Netflix realised that you could spend far more money on far more hours of scripted drama than anyone had ever spent before, and you could (hopefully) make your money back by selling it on subscription directly to consumers instead of going through aggregators, using a new technology, broadband internet, that both gave you that access and made it possible for people to browse that vast selection of shows. And like Sky, Netflix has built a big business. It has around 150m paying customers, and the analyst consensus is that it will spend around $15bn on content this year, which is more than any of the US incumbents will spend, excluding sports rights. (It’s also 4x more than the combined budget of all the UK broadcasters.)

Like Sky, Netflix has used technology as a crowbar to build a new TV business. Everything about how it executed that technology has to be good. The apps are good, the streaming and compression are good, the UI is good, the recommendation engine is good, and the customer service and experience are good. Unlike American cable subscribers, Netflix subscribers are generally pretty happy with the tech. The tech has to be good - but, it’s still all about the TV. If Netflix was only showing reruns of Frasier and Ally McBeal no-one would have signed up. It used tech as a crowbar, and the crowbar had to be good, but it’s actually a TV company.

An interesting word to think about here is ‘commodity’. It’s challenging to call things like user experience or indeed software commodities, especially when talking to people who work in software. These are certainly not easy things to do, and when incumbents from other industries try to build them (‘we can just hire some techies!’) they often mess them up. But that doesn’t mean they‘re defensible, and it doesn’t mean they’re what determines success.

You can see this pretty clearly if you contrast Netflix with Hulu. The reasons that Hulu doesn’t have 150m paying customers have nothing to to with its technology, which is actually pretty good, even though Hulu is owned by legacy content manufacturers. Hulu is smaller than Netflix because of TV questions, not tech questions - because of rights and channel conflict and its shareholders’ broader strategies for monetizing their assets.

I think this framing is important - ‘what kind of questions matter for this business?’ The questions that mattered for Hulu were all TV questions - ‘what rights will it get?’ The same for Sky - ‘what happens to football and movie rights?’ - and the same for Netflix. As I look at discussions of Netflix today, all of the questions that matter are TV industry questions. How many shows, in what genres, at what quality level? What budgets? What do the stars earn? Do you go for awards or breadth? What happens when this incumbent pulls its shows? When and why would they give them back? How do you interact with Disney? These are not Silicon Valley questions - they’re LA and New York questions. I don’t know the answers - indeed, I don’t even know the questions.

The more that we see new companies using software to create new businesses in industries outside of technology, the more generally this applies. In particular, I find this a useful way to look at, for example, the explosion of so-called ‘D2C’ - companies that are creating new consumer goods and selling them online ‘directly to consumers’ instead of going through existing retailing channels (at least to begin with). For all of these companies, it’s crucial to execute the online channel properly - the user acquisition model and funnel and browsing and shopping cart and logistics and so on all have to be good. It’s not easy to do this, and we often see legacy, physical retailers struggling. But again, executing this properly is not the same as defensibility. Selling online per se - even selling online really well - is fundamentally a commodity. Hence, one asks whether there is something unique and defensible about this company’s online channel - which would probably be some kind of network effect. Or, is this a makeup/bag/shoe/soap company, with a website? Is the online channel the crowbar you’re using to enter the market, but success is actually all about the makeup (in which case, is there something about the makeup that only tech people can do)? In other words, how much are we asking ‘tech’ questions and how much are we asking CPG questions? Do we even know what to ask, and who does?

Coming back to TV, there’s an irony here in the fact that the tech industry has spent decades wanting to get into the living room, get into TV, break up the cable bundle and move TV from scheduled linear to on-demand, and yet now that it’s happening, it’s happening in the TV industry, not the tech industry.

There are several things to unpack here. First, the tech industry did get into the living room, and did break out of the hobbyist niche of the PC, but the way to do that at the scale of billions of people turned out to be with smartphones, not smart TVs or games consoles or ‘interactive TV’. The actual television hardware itself is just a low-margin smartphone accessory.

Second, and perhaps more interesting, though, is the way that content has largely lost its strategic value for technology companies, as I argued in detail here. When we bought content (whether music, ebooks, video or indeed VHS cassettes), we were committing ourselves to one standard or to one company’s platform, and so getting the content onto your company’s platform or device or standard was a way to get a customer and then to keep that customer. Buy a different device and you lose all the music you already bought. But now that we’ve gone to cloud and subscription, you can access the same service on any device (Netflix, Spotify, Kindle), or the same content on any service (music, books), or both. Content doesn’t stop you switching - unless it’s exclusive, and that’s a totally different budget. That changes its strategic value.

Hence, Netflix isn’t using TV to leverage some other business - TV is the business. It’s a TV company. Amazon is using content as a way to leverage its subscription service, Prime, in much the same way to telcos buying cable companies or doing IPTV - it’s a way to stop churn. Amazon is using Lord of the Rings as leverage to get you to buy toilet paper through Prime. But Facebook and Google are not device businesses or subscription businesses. Facebook or Google won’t say ‘don’t cancel your subscription because you’ll lose this TV show’ - there is no subscription. That means the strategic value of TV or music is marginal - it’s marketing, not a lock-in.

Apple’s position in TV today is ambivalent. You can argue that the iPhone is a subscription business (spend $30 a month and get a phone every two years), and it certainly thinks about retention and renewals. The service subscriptions that it’s created recently (news, music, games) are all both incremental revenue leveraging a base of 1bn users and ways to lock those users in. But the only important question for the upcoming ‘TV Plus’ is whether Apple plans to spend $1bn a year buying content from people in LA, and produce another nice incremental service with some marketing and retention value, or spend $15bn buying content from people in LA, to take on Netflix. But of course, that’s a TV question, not a tech question.