The latest Israeli heightening of violence in an already violent region presents the Biden administration with one of its biggest challenges yet in keeping the United States out of a new Middle East war.

Israel’s bombing of an Iranian diplomatic compound in Damascus, killing a senior commander in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps and several other Iranian officials in addition to at least four Syrian citizens, was a marked escalation. Besides being as much an act of aggression in Syria as many previous Israeli aerial attacks, hitting the embassy compound constituted a direct attack on Iran.

Iranian leaders will feel heavy pressure to respond forcefully. The extent of that pressure can be appreciated by imagining if the roles were reversed. If Iran had bombed an embassy of Israel or the United States, a violent and lethal response would be not just expected but demanded by politicians and publics alike.

In Iran, too, popular sentiment can play a similar role in such situations, as illustrated by the outpouring of public emotion when a U.S. drone strike assassinated prominent Revolutionary Guard commander Qassem Soleimani four years ago. In a more calculated vein, just as a need to “restore deterrence” is often heard as a justification for violent responses by the United States or Israel, so too can such calculations figure in Iranian decision-making.

Speaking a day after the attack, Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei vowed revenge and said “Israel will be punished.” The Iranian representative at the United Nations Security Council asserted Iran’s right to a “decisive response to such reprehensible acts.”

Iranian leaders feel pressures in the other direction as well. Involvement in a new war would not be in Iran’s interests, and its leaders have not been seeking such a war.

Reasons include Iran’s decided military inferiority vis-à-vis Israel or the United States and its profound economic problems. A principal reason that regional tensions centered on the tragic circumstances in the Gaza Strip have not escalated any more than they have so far has been the restraint that Iran has displayed in the six months since Hamas’s attack on southern Israel (an attack that surprised Iranian leaders as much as anyone else).

But Iran will respond to the Israeli attack somehow. Predicting exactly which of the options available it will use is as difficult as Iranian leaders’ own decisions will be, as they try to balance the conflicting considerations weighing on them. All one can say with confidence is that Iranian responses will be at times and places of Tehran’s choosing.

Several possible lines of speculation could apply to Israel’s motives in attacking the embassy compound in Damascus. Perhaps Israel viewed this as one more operation in its years-long campaign of aerial bombardment of Iran-related targets in Syria. Intelligence presented a target of opportunity with the IRGC officers at the embassy compound, and Israel seized the opportunity.

Or one might view the attack as one more manifestation of the uncontrolled national rage that has characterized Israel since the Hamas operation in October. This may be the kind of damaging and careless striking out about which President Biden warned when he told Israelis last October that Americans understood “their shock, pain, and rage” but that Israel should not be “consumed” by that rage. He noted that the United States had “also made mistakes” amid its rage after 9/11 — an oblique reference to launching an offensive war against Iraq, a country that had nothing to do with the 9/11 attack.

But the bombing of the embassy facility in Damascus was a clear enough escalation (and expansion of Israeli offenses against the laws of war), that it probably reflected a carefully calculated decision at the highest levels of Benjamin Netanyahu’s government. The calculation did not have much to do with any dent, which is likely to be short-term and minimal, that loss of the IRGC officers would make in Iranian capabilities.

Rather, the attack was part of an effort to escalate Israel’s way out of a situation in which its declared objective of “destroying Hamas” is out of reach, the worldwide isolation of Israel because of its actions in Gaza is becoming undeniable, and even its habitually automatic U.S. backing has patently softened. For Netanyahu personally, escalating and expanding the war, insofar as this also means continuing it indefinitely, is also his only apparent hope for staving off his political and legal difficulties.

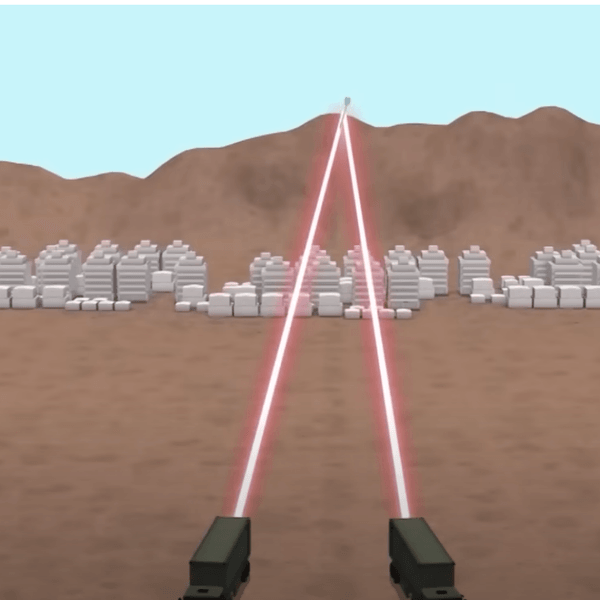

Escalation as an intended way for Israel to work its way out of the Gaza dead end has two elements. The main one is to provoke Iran to hit back, which can enable Israel to present itself as defending rather than offending and to push debate away from the destruction it is wreaking on Gaza and toward the need to protect itself against foreign enemies. The other element is to increase the chance of the United States getting directly involved in conflict with Iran. If it does, war in the Middle East would be seen as not just a matter of Israel bashing Palestinians but instead would involve equities of Israel’s superpower patron.

The United States could get dragged into an Israeli-Iranian conflict in either of two ways. One would be through political demands within the United States for Washington to act more directly to defend “our ally Israel” when under attack from Iran.

The other way is for Iranian reprisals against Israel to extend as well to U.S. targets. The plausibility of this — despite Iran’s military inferiority — becomes understandable with some more role-reversal thinking. There never is any hesitation in the United States to blame Iran for whatever recipients of its aid do, even if — as with Hamas’ October attack on Israel — Iran was not involved in the client’s action. Thus, for example, columnist David Ignatius writes that “Israel has a righteous cause in combating Hamas and its paymasters in Iran.”

Israel’s paymasters in Washington have provided it far more than Iran ever provided to Hamas or any of its other friends. This fact underlies the statement by the Iranian representative at the Security Council that “the United States is responsible for all crimes committed by the Israeli regime.” That, and the fact that the Israeli attack on the Iranian embassy compound in Damascus, like the Israeli flattening of neighborhoods in Gaza, was carried out with U.S.-provided advanced military aircraft.

A war with Iran would be highly damaging to U.S. interests for many reasons, including the direct human and material costs, the disruption to economic activity affecting Americans, the foreign resentment leading to additional violent reprisals, the torpedoing of worthwhile diplomacy, and the diversion of attention and resources from other pressing concerns of U.S. foreign policy.

Avoiding such a war requires not only deft statesmanship in dealing tactically with crises but also a more strategic distancing from the odd relationship with Israel that has gotten the United States into its current difficult and dangerous situation. The United States needs to move away from time-worn notions of who is an ally and who is an adversary and to pay attention to who is an aggressor and who is not.

Despite frequent references in symmetrical terms to a “shadow war” between Iran and Israel, a compilation of events in that war shows an asymmetrical pattern of Israel initiating most of the violence and Iran mostly responding. For the United States to distance itself from this pattern would be not only in U.S. interests but also the interests of regional peace and security.

- US is barreling toward another war in the Middle East ›

- Will US troops be drawn into the Israel-Gaza war? ›

- By caving to Israel, Biden opens the door to war ›

- Report: Iran says it won’t strike Israel if US gets Gaza ceasefire | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Biden should not follow Netanyahu into war with Iran | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Iran launches risky attack on Israel | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Iran's risky bid to redefine deterrence with Israel | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Israel can still drag the US into war with Iran | Responsible Statecraft ›

- What the US should learn from Israel's aerial tit-for-tat with Iran | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Iran, US mutual delusions pave a path to war | Responsible Statecraft ›

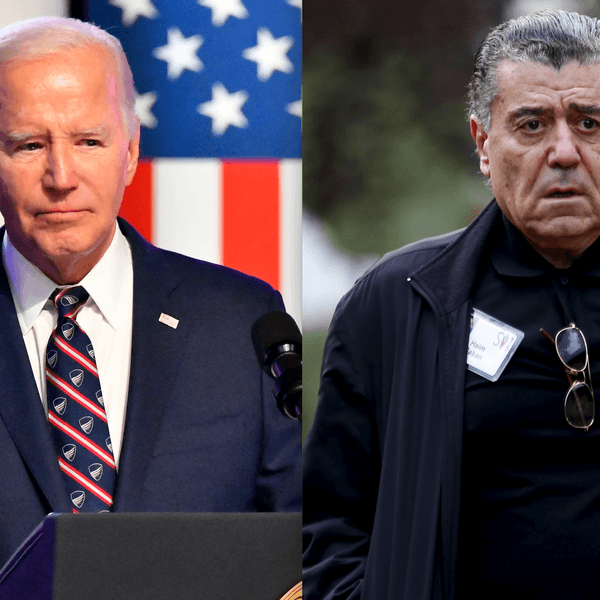

![Following a largely preordained election, Vladimir Putin was sworn in last week for another six-year term as president of Russia. Putin’s victory has, of course, been met with accusations of fraud and political interference, factors that help explain his 87.3% vote share. If this continuation of Putin’s 24-year-long hold on power makes one thing clear, it’s that he and his regime will not be going anywhere for the foreseeable future. But, as his war in Ukraine continues with no clear end in sight, what is less clear is how Washington plans to deal with this reality. Experts say Washington needs to start projecting a long-term strategy toward Russia and its war in Ukraine, wielding its political leverage to apply pressure on Putin and push for more diplomacy aimed at ending the conflict. Only by looking beyond short-term solutions can Washington realistically move the needle in Ukraine. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, the U.S. has focused on getting aid to Ukraine to help it win back all of its pre-2014 territory, a goal complicated by Kyiv’s systemic shortages of munitions and manpower. But that response neglects a more strategic approach to the war, according to Andrew Weiss of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, who spoke in a recent panel hosted by Carnegie. “There is a vortex of emergency planning that people have been, unfortunately, sucked into for the better part of two years since the intelligence first arrived in the fall of 2021,” Weiss said. “And so the urgent crowds out the strategic.” Historian Stephen Kotkin, for his part, says preserving Ukraine’s sovereignty is critical. However, the apparent focus on regaining territory, pushed by the U.S., is misguided. “Wars are never about regaining territory. It's about the capacity to fight and the will to fight. And if Russia has the capacity to fight and Ukraine takes back territory, Russia won't stop fighting,” Kotkin said in a podcast on the Wall Street Journal. And it appears Russia does have the capacity. The number of troops and weapons at Russia’s disposal far exceeds Ukraine’s, and Russian leaders spend twice as much on defense as their Ukrainian counterparts. Ukraine will need a continuous supply of aid from the West to continue to match up to Russia. And while aid to Ukraine is important, Kotkin says, so is a clear plan for determining the preferred outcome of the war. The U.S. may be better served by using the significant political leverage it has over Russia to shape a long-term outcome in its favor. George Beebe of the Quincy Institute, which publishes Responsible Statecraft, says that Russia’s primary concerns and interests do not end with Ukraine. Moscow is fundamentally concerned about the NATO alliance and the threat it may pose to Russian internal stability. Negotiations and dialogue about the bounds and limits of NATO and Russia’s powers, therefore, are critical to the broader conflict. This is a process that is not possible without the U.S. and Europe. “That means by definition, we have some leverage,” Beebe says. To this point, Kotkin says the strength of the U.S. and its allies lies in their political influence — where they are much more powerful than Russia — rather than on the battlefield. Leveraging this influence will be a necessary tool in reaching an agreement that is favorable to the West’s interests, “one that protects the United States, protects its allies in Europe, that preserves an independent Ukraine, but also respects Russia's core security interests there.” In Kotkin’s view, this would mean pushing for an armistice that ends the fighting on the ground and preserves Ukrainian sovereignty, meaning not legally acknowledging Russia’s possession of the territory they have taken during the war. Then, negotiations can proceed. Beebe adds that a treaty on how conventional forces can be used in Europe will be important, one that establishes limits on where and how militaries can be deployed. “[Russia] need[s] some understanding with the West about what we're all going to agree to rule out in terms of interference in the other's domestic affairs,” Beebe said. Critical to these objectives is dialogue with Putin, which Beebe says Washington has not done enough to facilitate. U.S. officials have stated publicly that they do not plan to meet with Putin. The U.S. rejected Putin’s most statements of his willingness to negotiate, which he expressed in an interview with Tucker Carlson in February, citing skepticism that Putin has any genuine intentions of ending the war. “Despite Mr. Putin’s words, we have seen no actions to indicate he is interested in ending this war. If he was, he would pull back his forces and stop his ceaseless attacks on Ukraine,” a spokesperson for the White House’s National Security Council said in response. But neither side has been open to serious communication. Biden and Putin haven’t met to engage in meaningful talks about the war since it began, their last meeting taking place before the war began in the summer of 2021 in Geneva. Weiss says the U.S. should make it clear that those lines of communication are open. “Any strategy that involves diplomatic outreach also has to be sort of undergirded by serious resolve and a sense that we're not we're not going anywhere,” Weiss said. An end to the war will be critical to long-term global stability. Russia will remain a significant player on the world stage, Beebe explains, considering it is the world’s largest nuclear power and a leading energy producer. It is therefore ultimately in the U.S. and Europe’s interests to reach a relationship “that combines competitive and cooperative elements, and where we find a way to manage our differences and make sure that they don't spiral into very dangerous military confrontation,” he says. As two major global superpowers, the U.S. and Russia need to find a way to share the world. Only genuine, long-term planning can ensure that Washington will be able to shape that future in its best interests.](https://responsiblestatecraft.org/media-library/following-a-largely-preordained-election-vladimir-putin-was-sworn-in-last-week-for-another-six-year-term-as-president-of-russia.jpg?id=34283894&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C77%2C0%2C77)