In roulette, the Martingale system is a strategy where the gambler bets at near-even odds and doubles down after each loss, hypothetically allowing them to tuck away their wins and recoup their losses. It doesn’t always work out that way, as filmmakers Clay Tatum and Whitmer Thomas learned a few years ago when they used it to try financing an entire movie.

After several years of trying to get a small Alabama-set comedy called The Mailmen made, the project was stalling. So, they sketched out an idea for a different movie designed to be made in the most bare-bones way imaginable. It had a gambling element. Wouldn’t it be a fun story to finance it through roulette? They spent a week driving Thomas’s old champagne-colored Camry through the desert, to the nearest casino, two hours from their homes in Los Angeles. They parked themselves before the roulette machine with the pretty woman, and pointed at each other before each automated roll, yelling nonsense like “Money Tony!” and “Monkey mode!”

And it worked. After five trips, they almost had enough to finance their little movie. They were feeling invincible—until the sixth trip. That day, the ball stopped rolling their way, and, before they knew it, they lost it all and were back in the Camry riding through the vast desert in silence.

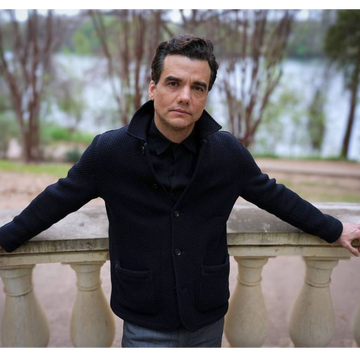

It’s an unseasonably warm February day, four years later, when Tatum and Thomas tell me this story over lunch at Spicy Village, in Manhattan’s Chinatown. The pair, who could pass as the Southern nephews of Zach Galifinakis and Jim Carrey, pause every now and then to slurp down soup and dumplings. They’re in town because not too long after the gambling loss their luck changed. An old friend called Tatum after seeing one of his shorts. He wanted to produce a feature, and had thirty grand to invest. Do you two have any ideas?

Now, here’s the thing about thirty grand: in the real world, it’ll buy you a dependable car, or cover a year’s rent. But in Hollywood? It gets you a pack of gum. It’s enough to finance one glorious motion-smoothed second of Avatar: The Way of Water, an accounting error on a Marvel movie’s cape budget, a lowball offer for rights to a Led Zeppelin song. In 1996, before inflation made eggs luxury goods, Swingers was made for $250,000 (about $470,000 today), and that was considered a feat of low-budget filmmaking.

But the bet Tatum and Thomas were willing to make—and they were playing with house money now, so why not?—was that they could make something with thirty grand that rivals the quality of a multi-million dollar movie. And not, mind you, by neglecting to pay their cast and crew. No. Their producers had access to basic equipment. And having spent years making short films and acting in some bigger budget fare, Tatum and Thomas saw ways to strip away the excesses of moviemaking: trailers, trucks, walkie-talkies, makeup tents, and so forth. “We keep saying [to other filmmakers], 'Why do you think you need all these things to make a movie?'” Thomas says.

The film they made is a supernatural buddy comedy called The Civil Dead, and it makes their case convincingly. When I first saw it, through last year’s virtual Slamdance (where it won the Audience Award), it brought to mind revered auteurs like Robert Altman and Albert Brooks. But it also felt like the product of a distinct new voice, a clear reflection of Tatum and Thomas’s offbeat sense of humor, brotherly chemistry, and veritable filmmaking prowess. As for the production value? If I’d stumbled across it on a streaming platform, I probably wouldn’t pick up on it having been made for 100 or 1,000 times less than most other content.

Tatum and Thomas, mind you, aren’t the only filmmakers who have pulled off this feat. The Civil Dead is the latest in a wave of microbudget features that are pushing what’s possible with no money. Over the past few years, as the “movies are dead” chorus has grown louder, tiny indies like Emma Seligman’s Shiva Baby, Jane Schoenbrun’s We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, and Kyle Edward Ball’s Skinamarink have shown that a dire industry landscape couldn’t suppress a rising swell of weird, wacky, and creative voices.

In February 2020, it would’ve almost seemed easy for Tatum and Thomas to hustle up half a million dollars to make The Mailmen. Thomas’s face was on billboards throughout Los Angeles, promoting The Golden One, his Tatum-directed HBO special about coping with the death of his mother. Then the pandemic hit, stifling all momentum. With the pair’s attempts to make a movie floundering, Thomas remembers his dad sending him an interview in which Matt Damon and Ben Affleck explain how they got Good Will Hunting made in the ’90s. “My dad was like, ‘See, this is how they did it,’” Thomas says, referencing how they wrote their own starring vehicle. “And I’m like, ‘That’s not how it’s done anymore.’ And I think Hollywood is still in this Good Will Hunting mode. And everything is just not the same.”

There is, of course, no one way to jumpstart a career making ambitious, original movies today. Even in the 1990s, it was rare for a couple of up-and-comers to star in a $10 million prestige drama they wrote on spec—and rarer still if they didn’t look like Damon and Affleck. But as Hollywood has become ever more polarized between big franchises and little indies, pulling a Matt-and-Ben has become increasingly farfetched. “It seems like a lot of financiers and companies are less interested in unique voices and taking risks, and more interested in selling to a big streamer,” says Tatiana Bears, who co-produced the raucous A24 slasher comedy Bodies Bodies Bodies.

Where the big streamers at first offered a bastion of possibility—throwing around money willy-nilly, supporting auteurs—the new oligopoly they’ve created has largely crowded out fresh talent. “From a producing perspective, if you're trying to pitch a project to the four or five streaming platforms who actually are able to pay for things, they want what the algorithm is telling them they want,” says Riel Roch-Decter, co-founder of MEMORY, an indie production company. “That means more true crime, more Emily in Paris, and not anything that challenges.”

Many aspiring filmmakers learned that lesson the hard way, spending years trying to break in through establishment channels before having a realization like Inspector Ike director Graham Mason’s: “With the movie industry, there's this notion that you want to get invited to their cool party. But what you actually need to do is make your own cool party with whatever limited means you have. Then hopefully the industry comes and they knock on your door and ask to be let in. And if they don’t, that’s OK too, because you didn’t just wait around.” (Mason was quick to point out that “it's privileged people who get to do that.”)

The do-it-yourself approach to building a filmmaking career is far from new. But as the proverbial party has shrunk, advances in filmmaking technology have made it easier for upstarts to create a party just as good as the industry’s. Over the past decade, high-quality cameras, lenses, lights, and sound equipment have become cheaper and more accessible, and all manner of filmmaking tutorials have proliferated on YouTube. Filmmakers who are strategic with their locations and able to find a cinematographer and sound op who own their equipment—and there are many—are left spending on insurance, labor (hopefully), food, and, potentially, music licensing, props, and wardrobe. Pete Ohs, whose superb $10K stalker-ghost movie Jethica was released on Fandor this month, has developed a process whereby he acts as his own crew, further reducing expenditures. “The technology has continued to develop to where the playing field is equal,” says Kentucker Audley, who co-directed Strawberry Mansion with Albert Birney. “But that's the more boring part of the change.”

A little over a decade ago, Audley–who speaks softly and has a formidable mustache–was growing disillusioned with mumblecore, the naturalism-prizing movement he’d helped shape. “[I was] coming to terms with just how disinterested everyone was in the movies I was making,” he says. Though Audley recognized the need to shift gears, he still wanted to champion work that was made in the spirit of mumblecore—films that are authentic, honest, and “feel like the expression of a human being rather than a template or a craft.” He remembers thinking, There isn't an audience for this kind of work, but there should be.

That impulse led Audley to create NoBudge, which, over the past twelve years, has blossomed from a curated Tumblr blog into a bonafide streaming platform for DIY short films and a bi-monthly live screening series in Brooklyn (which, full disclosure, has programmed films I’ve made). With a lower barrier to entry than digital platforms like Short of the Week or Vimeo Staff Pick, NoBudge is in no way a career-maker. But over the past decade, it is one of several outsider-embracing platforms—like MEMORY, The Eyeslicer, Future of Film Is Female, and the more recent Dezda Films and Eternal Family collective—that has fostered work from filmmakers who are throwing their own parties.

NoBudge is particularly significant because of its ongoing interplay between the digital and physical. Its recurring live screenings serve as a hub for the New York film scene, encouraging community-building and creative cross-pollination. “I don't know if people [in the scene] would've gotten to know each other without that connective thing,” says Ryan Martin Brown, a Brooklyn filmmaker who was introduced to Colin Burgess, the lead of his forthcoming debut feature, Free Time, through NoBudge. And NoBudge’s online dimension has placed a local scene within a broader constellation, with many micro scenes orbiting each other and sometimes colliding.

Not all of the filmmakers who have made invigorating microbudget features in recent years have ties to NoBudge, but many do. And the ethos of the site—which prizes a distinct voice, playful spirit, and independent mentality—is reflected in these films’ general trajectory. Where mumblecore was characterized by improvisational realism, a messy DV aesthetic, and postgrad malaise, today’s No-budgers tend to be scripted, aesthetically ambitious, and thematically unbound. They might make a Columbo-style ‘70s murder mystery, a future-set dream auditing sci-fi adventure, a zany suburban witness protection comedy, a Lynchian twin-on-the-run small town thriller, a square-framed queer Hebrew school coming-of-age drama, or a mother-daughter comedy about eviction.

These are, for the most part, highly personal works—about their authors’ identities, anxieties, and relationships—but they’re coming at self-expression from different angles. “Mumblecore was very self-obsessed and inward looking, and I think over the last five or ten years a lot of the successful filmmakers have gotten outside of themselves and looked at a wider scope of the world and not just these issues of love and finding love,” says Audley.

But where these filmmakers have figured out how to make professional-looking, yet idiosyncratic movies on the cheap, getting their films noticed without A-list stars and ample marketing capital remains tricky. “There are filmmakers everywhere doing cool stuff,” says Kyle Greenberg, head of marketing and distribution for the indie distributor Utopia. “It's harder than ever to get your stuff seen. And this has been the case for a while. The question is: How do you get through all the noise?”

“Just cast a celebrity in your movie,” Whitmer Thomas says with a sly grin. He and Tatum are scrunched into big, awkward director's chairs, sitting beside Joe Pera, who is moderating a post-screening Civil Dead Q&A in front of a packed theater at the Manhattan Alamo Drafthouse. Thomas is responding to an audience member who asked for advice on getting your movie bought—but he quickly revises his answer: “Or! Become a celebrity… Or! What do your parents do? Are they famous? No? Well, then you're kind of fucked.”

“My dad is Zac Efron,” Tatum deadpans.

The telepathic banter I’d observed over lunch, and which is palpable in their movie, carries onto the stage, with the pair riffing about everything from The Joker (Pera: “American Hamlet?”) to who they’d most like to be haunted by (Thomas: “Pamela Anderson!”). “Probably the funniest Q&A I’ve ever attended,” one Letterboxd reviewer later wrote of the event. Afterward, the pair takes pictures with fans and signs t-shirts with Thomas’s face on them.

This is surely what Utopia—which is distributing The Civil Dead—hoped for when it sent Tatum and Thomas on a tour around the country: sold-out shows, chortling crowds, the first flickers of buzz. The company has quickly established itself as something of a AAA24 since its 2018 founding. And despite its comparatively scant resources, it’s had success forging excitement around other recent microbudget features from freshmen filmmakers, such as Emma Seligman’s Shiva Baby and Jane Schoenbrun’s We’re All Going to the World’s Fair. “What I'm taking away right now is that word of mouth is everything,” says Seligman, who watched as Shiva Baby built momentum slowly over a nine month-long pandemic rollout that included many virtual festivals.

Unfortunately, there’s no foolproof formula for generating word of mouth without a Disney-level marketing budget. “Word of mouth is like this elixir that everyone knows works, but no one knows how to make it,” says Derek Thompson, author of Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction.

Utopia has been strategic about selecting projects, and employing what Thompson calls the “bowling ball strategy”: Identifying affinity groups for a given movie—in the case of Shiva Baby, the young queer and Jewish communities—and targeting them where they congregate, such that when you bowl you hit as many pins as possible. But Utopia has consistently bowled down one lane in particular. “A big part of what's led to debut film successes for us is younger audiences really coming out and supporting these films theatrically,” says Kyle Greenberg. “We're constantly going for these younger audiences, who frankly I think have been underserved and not always respected.”

But the key to breaking out, to Schoenbrun’s mind, comes down to making something “that the commercial landscape is going to be too conservative to actually invest in.” In that way, these films could be a bellwether for the broader industry. While the no-budgers’ films are thematically and aesthetically diverse, there are a couple throughlines. In particular, slowness and comedy. In an age of nonstop stimulation, part of the appeal of films like We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, Skinamarink, and this year’s Slamdance-winning drama, Waiting For the Light to Change, is their methodical pacing. They force the viewer to settle in and pay attention to small details. Similarly, at a time when Hollywood has all but abandoned big-budget comedies, many filmmakers were motivated to fill the void. “I think there's a vast pool of talent from the Brooklyn comedy scene, and it's been underutilized,” says Tynan DeLong, whose NoBudge-presented Dad & Step-Dad is hitting select New York theaters this month.

Preferences around things like pacing and genre, though, always go in waves. Right now, the bigger question for this group of filmmakers is whether—and how—the industry will make space for them.

Around the time Tatum and Thomas toured The Civil Dead around the country, Jane Schoenbrun and Emma Seligman were finishing postproduction on their sophomore features, I Saw the TV Glow and Bottoms. The success of their respective debuts had landed them both the sorts of situations most filmmakers dream of: formidable budgets (the former around $6 million, the latter around $10 million) to tell the weird, personal stories they wanted to tell–the way they wanted to tell them. Each of them was over the moon that Orion and A24, respectively, had given them the opportunity. “It was completely surreal,” Schoenbrun says. “Every day I was [on set] felt like I was living in a child's dream.”

But the jump in budget came with challenges. Seligman, in particular, was feeling “destroyed mentally and physically” from the mix of crazy hours and set politics. Leading a team of 200 some-odd people slowed the process–and sowed conflict. She noticed certain crew members “not wanting to work for a young woman” and “pretending they were listening to me when they weren’t,” which was a far cry from the experience of making Shiva Baby with a small group of like-minded friends. “I had a moment where I was like, Do I want to keep doing this? Every time I talked to a mentor I was like, This can't be what all my heroes go through every time they make a movie. They were like, No, this is universal. I had a nervous breakdown on my last movie.”

More money adds pressure to deliver a product that meets the expectations of more stakeholders. But it also adds union regulations. There are various budgetary thresholds that dictate the rules a production must adhere to, making some of the moviemaking machinery that Tatum and Thomas detest unavoidable. Still, microbudget films are no panacea. They frequently rely on free labor from friends. The ones that do pay, by necessity, do not pay well. Worse, low-budget indies are notorious for exploitative and unsafe behavior. “I'm very cautious of putting the idea of making art in this [DIY] way on a pedestal,” says Jess Zeidman, who wrote and produced the $120K queer coming-of-age drama Tahara (2020). “Because this is not the ideal. At this budget level, it can be hard to find the line between saving money and taking advantage of people's experience. It's very blurry.”

Some of these filmmakers also worry that Hollywood will take the wrong lessons from these movies. At the moment, the ability to make a $50,000 feature that rivals the quality of something made for $5 million is an exciting democratization, but it’s easy to imagine how that advancement might be exploited. “The second you tell people who finance movies that they're paying five million dollars for something they could be paying fifty grand for, we're just going to continue to erode at the idea that anyone could ever make a living doing this,” says Free Time director Ryan Martin Brown.

Derek Thompson thinks the gulf between the biggest and smallest movies will continue to widen. “The future is going to be city-states and empires,” Thompson says. “The biggest hits, like Avatar, are going to be bigger than ever. But the Internet also creates the possibility for hits that are incredibly niche.” This change, of course, has already hit movies, where a greater and greater share of the pie goes to just a few pieces of IP. But it remains incredibly difficult for a small indie—even one that’s critically acclaimed—to make its money back. Thompson wondered if something in the vein of Substack could make it easier for the microbudget filmmakers of the world to make a modest living: “How do we create a successful business model for these micro films?”

A lot of people in the business are wondering the same thing. Matt Grady’s Factory 25 has long supported these types of films in distribution, and arthouse streamers like Fandor and Mubi are quickly filling their libraries with them. Tatum and Thomas hope an independent studio crops up to do for comedy what Blumhouse has done for horror. The sense I get, though, is that the solution—if there is one—will involve theaters. There’s been a lot of handwringing over the past decade that streaming has killed the theatrical business for everything other than Marvel movies. Programmers, distributors, and independent studios though, say that that’s not totally true. Evenings like the one I witnessed with The Civil Dead or at NoBudge screenings were doing well, too. In other words: Events. “People really enjoy when there's a live component,” says Future of Film Is Female Executive Director and longtime programmer Caryn Coleman. “I like showing short films before features because you get their whole audience to come in.”

The No Budge Starter Pack

Where to watch the movement's biggest hits.

We're All Going to the World's Fair

At the moment, the theaters successfully pivoting in that direction are mostly in big cities with big populations of cinephiles. But could that change? Will more of an indie filmmaker’s livelihood come from touring? And would such a landscape strengthen cinema’s foundation, bolstering viewers’ voraciousness for all sorts of movies? Or will it cut the legs out from already endangered mid-tier movies? At times, I’ve thought I was witnessing a new generation of future stars—that talents like Inspector Ike’s Matt Barats, El Planeta’s Amalia Ulman, and Youngstown’s Stephanie Hunt would soon be household names. But maybe these performers' fame will increasingly be contained in siloed scenes. Maybe it’ll become more and more common for filmmakers to follow in the footsteps of Pete Ohs and make professional-grade features purely for the fun of it.

In an ideal world, microbudget movies will continue to be an avenue to bigger swings—while becoming a sustainable lane of their own. And filmmakers who do level up might be better able to retain the intimate, stripped-down workflow Tatum and Thomas are advocating for. There’s been a lot of talk in recent years about reforming on-set hours and toxic filmmaking norms. Ultimately, most of the filmmakers I spoke to were optimistic about the future—both for their own careers and the medium. Though, it’s still up in the air whether this crop of filmmakers is poised to take the industry by storm, or if this sort of film is. “We're in a changing period, and my outlook towards it is more positive than negative,” says Tatum. “More people are noticing that you can make more with less. I hope that in the next five years we're going to see lots of great new filmmakers making really interesting stuff for cheap. And it's going to also be profitable.”

Just before Tatum and Thomas caught a flight out of New York, I met them for burgers near their hotel. The previous night, after the Civil Dead screenings, we stopped by a party celebrating the release of Hannah Ha Ha, another charming film that premiered in New York that day. The pair were visibly tired, caught somewhere between appreciating the positive response to their movie and feeling like they’d only begun rolling the boulder up the hill. Studios weren’t suddenly knocking on their door with a bag of cash. But they’d recently found out that The Civil Dead was playing at one of their favorite Los Angeles theaters–and when they told me, they sprang to life. “Our whole dream was to have it play at the Laemmle Glendale,” says Thomas. “And it's playing there. So we did it.”

As for The Mailmen? “You know what, Clay?” Thomas says. “We should try to add a gambling element to The Mailmen.”

Tatum shakes his head. “He's obsessed. It's scary.”