Venmo’ing $1,000 to a total stranger on the internet is a pretty reliable sign that something has gone wrong in your life. When Amy Webb prepared to send that not-at-all-insignificant amount of money to Keith Williams, both parties would’ve actually preferred not to be part of the transaction: Ideally, Webb would’ve bought tickets to Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour directly from Ticketmaster, and Williams wasn’t exactly thrilled to have tickets he felt a moral obligation to sell. But the thing is: Williams’s tickets were meant for people with accessibility needs.

The Taylor Swift Eras Tour ticket rollout failed fans across the board, hard stop. From the bug- and bot-riddled presales to the abruptly canceled general sale, the entire ordeal was a nightmare for anyone who wanted to scream-shout the lyrics to “Anti-Hero” alongside Taylor herself. But the disability community was left particularly disappointed in a fumble that got far less attention than the wider snafu. The main difference between the nightmare most Swifties faced and the one that Swifties with accessibility needs faced was that the latter group one hundred percent saw it coming.

“Tickets for Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour [are] going to be hard to come by for everyone, but for the disability community, it’s going to be nearly impossible,” Webb, an author and disability rights advocate, predicted on Instagram days before the first presale was scheduled to start.

She was, unfortunately, correct. For many, getting ADA (Americans With Disabilities Act)-compliant accessible seating for the tour was an exercise in futility—and a tragic case study of all the ways people with disabilities are failed, forgotten, and outright discriminated against when it comes to live entertainment. During the presale, Webb tried and failed to get ADA accessible tickets for her daughter, who lives with limb differences and uses a wheelchair. On Twitter, she ended up connecting with Williams, who discovered that the tickets he had secured for his wife and 15-year-old daughter were for ADA-compliant seating. Williams, for his part, tried to rectify the situation right away.

“I called the venue [Paycor Stadium in Cincinnati] and asked, ‘Hey, is there any way to trade these?’ And they said, ‘No, you can’t do anything,’” Williams recalls. “They just kind of said, ‘Just enjoy the tickets,’ and I was like, ‘Well, that’s not what I want to do.’”

More than a quarter of American adults live with a disability of some kind, with mobility issues being the most common. These numbers are on the rise, particularly in the aftermath of the pandemic. It’s been more than 30 years since the Americans With Disabilities Act was supposed to usher in a new era for people with disabilities. So why are we still dealing with this clusterf*ck when simply trying to enjoy a concert?

Nothing New (Taylor’s Version)

If you’re not a member of the disability community (which, for the purposes of this article, refers to anyone who lives with a disability/an accessibility issue and their close friends and family), it’s depressingly easy to go through life unaware of these issues—and this is coming from someone who learned that lesson firsthand.

As a person living with an invisible disability, even my knowledge of the ADA was limited until five years ago, when I was matched with my service dog. Overnight, my disability went from completely invisible to, if not exactly visible, certainly strongly telegraphed. Just as suddenly, my accessibility needs changed too.

My service dog makes it possible for me to live my life in ways I had previously opted out of because, in the wise words of John Mulaney, it is so much easier not to do things than to do them. With my service dog, I started to remember I did actually want to do things and, more importantly, I was capable of doing them. So it’s ironic that the very thing that makes concerts accessible for me can often make the logistics of accessing public spaces a nightmare.

At many venues, my 70-pound service animal won’t fit at my feet in a standard seat. I quickly learned after early experiences buying aisle seats that having a dog the weight of an 11-year-old human hanging in the aisle of a darkened venue can range from simply inconvenient to a legitimate safety hazard.

Cut to me the second that tickets for the Eras Tour went on sale, nervously vying for the limited number of ADA accessible seats available at any venue within a six-hour drive of my home in Kentucky.

If you’re not a member of the disability community, you might assume that because the ADA exists, people with disabilities are able to access venues and live their lives like the varied humans with varied interests they are—but you would, in many cases, be wrong.

“Anytime someone brings up inaccessibility, people are like, ‘Oh my god, that should be illegal,’ but this is just what we encounter,” explains Cassie Wilson, whose own accessibility needs related to dwarfism inspired her to found Half Access, a nonprofit that facilitates crowdsourced accessibility information on venues around the world, when she was 18. “It’s so normal to me that inaccessibility is everywhere. It’s almost surprising to hear how non-disabled people react to it, because they’re like, ‘Oh my god, that’s horrible. That should be illegal.’”

The ADA might seem like a benevolent authority ready to save the day, but—as people across the disability community know all too well—it isn’t. In fact, it has no designated enforcement agency, meaning that, in practical terms, the only recourse for someone whose ADA rights are violated is to file a lawsuit…which is never a particularly attractive option, from a time/money/emotional well-being POV.

Death by a Thousand Cuts

Even when public spaces meet the minimum requirements for ADA compliance, people with disabilities can run into a range of practical challenges. For a popular event like a Taylor Swift concert, that includes just accessing tickets in the first place.

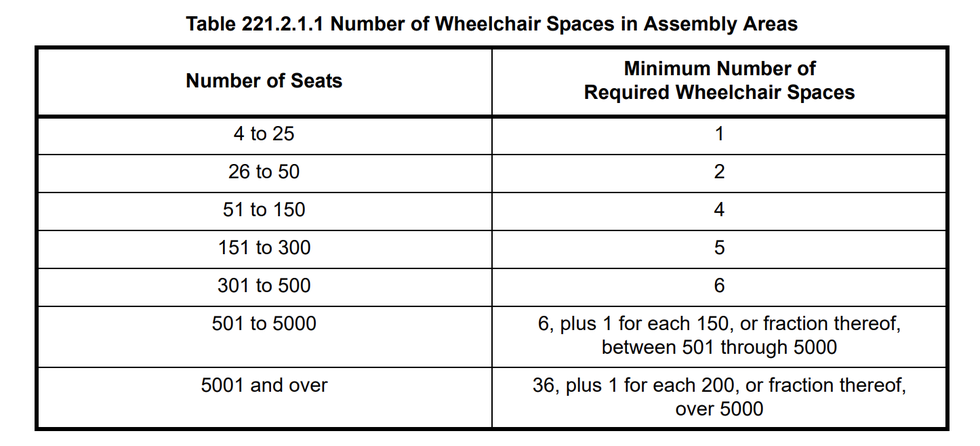

According to the law, 80,000-seat venues (like the biggest stadiums hosting Taylor) should have a minimum of 411 wheelchair spaces for ADA compliance, which works out to roughly 0.005 percent of total seats. That math ultimately means people in the disability community must compete for an excruciatingly limited number of seats.

Although the ADA regulations regarding ticket sales officially require venues to offer accessible-seating tickets across all price categories for a given show, there’s often little transparency about how (or if) venues implement this policy.

When Tessa Carpenter, who lives with multiple chronic illnesses and deals with mobility challenges, made it through the digital queue for the Eras Tour, there was ADA seating available but it was all prohibitively expensive—and not a fit for her specific needs. Tessa hoped to purchase seats that accommodated limited use of walking and stairs but didn’t see any listed. Because ADA accessible seating wasn’t a feasible option for her, Tessa ultimately bought tickets “up in the nosebleeds” but says she’s worried about her ability to climb the stairs required to get to them.

“I don’t feel like ADA seating should be $300 a ticket,” she says, noting that her earnings are also limited because of her disability. “People don’t realize that people with disabilities maybe don’t have that kind of money.”

Even when people in the disability community want to splurge on the best possible seats to see their favorite artist, that’s rarely—if ever—an option. Derrick Saenz-Payne has been dealing with ADA accessibility issues since 2007, when injuries from a car accident resulted in him having paraplegia.

“There’s always just this inherent base discrimination that no matter how much money I can even afford to spend, I’ll never be able to get to the front. I’ll never be able to get to the goal line or the floor seats,” he says. Because the ADA doesn’t require venues to offer ADA accessible options for many premium seats, he explains, venues simply don’t do it. “I know for a fact no matter what, as a father, I can never take my son or my wife to go see somebody front row in most of these venues because they don’t offer that.”

Vigilante Sh*t

After my own failed attempt to buy tickets during the Eras Tour presale, I looked on StubHub and was deflated to see that ADA seats were being immediately resold for as much as $5,400. Unfortunately, the ADA does little to ensure that accessible seats are sold to people who need them. That’s because the ADA (for very valid reasons) prohibits businesses from asking customers for proof or details about their disabilities. What’s more, the ADA explicitly prohibits venues from requiring ADA seats only be resold to others with disabilities, creating a perfect loophole for scalpers.

If this leaves you wondering where the blame lies and what can be done about the systemic mess that is ADA seating at live entertainment venues—same.

Enter: Vigilante Legal, a group of lawyers and other professionals (all of whom are self-identified Swifties) that formed in the wake of the Eras Tour presale, bonded by a mutual desire to do something not just about the ADA issues but also in response to the ways the Ticketmaster sale fell apart at every level.

Vigilante Legal aims to arm people with knowledge of how to advocate for their rights because, as the group’s founders say, karma is a well-informed public. Cofounder and legal scholar Jordan Burger says the group is also prepared to go further and has been compiling statements from fans affected by issues in the Eras Tour sale to send to the Department of Justice. They ultimately hope the DOJ will take action against Ticketmaster for antitrust violations.

“If the government won’t act, then yes, we would be, I think, at that stage prepared to take it on because at the end of the day, Ticketmaster needs to be held to account,” he said.

Ticketmaster released a public statement of its own after the mess, saying, “We want to apologize to Taylor and all of her fans—especially those who had a terrible experience trying to purchase tickets,” later releasing an explanation of what happened. Cosmopolitan reached out to Ticketmaster weeks ago for comment but has not heard back as of press time. Vigilante Legal has since sent a letter to the Federal Trade Commission asking the agency to investigate Ticketmaster for alleged fraud, misrepresentation, Americans With Disabilities Act violations, and multiple antitrust violations.

Although Ticketmaster’s own guidelines actually state that “accessible seating is reserved solely for fans with disabilities and their companions” and that “fans who abuse this policy could have their order canceled,” that’s a repercussion rarely enforced. Just look back at what happened to Keith Williams, the guy who sold his ADA tickets to Amy Webb and her daughter but was told by the venue to simply “enjoy the seats.”

Williams said the first and only indication he was purchasing ADA seats came on the final screen of his purchase, when hitting a back arrow could have meant exiting the Eras Tour sale completely. He decided to complete the purchase, assuming the venue would help sort out any mistakes. When the venue made it clear it couldn’t (or at least wouldn’t), he took matters into his own hands.

For her part, Webb says the problem starts with Ticketmaster—and any other company that looks to do the bare minimum for customers with disabilities. “At this point, all companies need to be addressing accessibility in a much more aggressive manner,” she says, adding that she hopes this situation will inspire more artists to take a stand in prioritizing accessibility and refusing to play venues that continue to fail fans with disabilities. In the meantime, she says the disability community and their allies are the ones who take on the burden of ensuring fair access.

“When systems fail us, it’s community that steps up,” she says. “That really has been my experience with my daughter as a wheelchair user. There’s the ADA, but I don’t think people understand just how bare bones that really is. That should always be seen as the jumping-off point rather than the ceiling.”