At the end of 2021, Taylor Jenkins Reid’s novel The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo had been on the New York Times bestseller list for 37 weeks. With over a million copies sold by the end of March 2022, Netflix announced that the book would be adapted for television by Liz Tigelaar, the showrunner and executive producer behind the Hulu limited series of Celeste Ng’s novel Little Fires Everywhere. This would be a major achievement for a just-published book, but for one that first hit shelves several years ago, in 2017, it was the equivalent of lightning striking twice. “We cannot keep Evelyn Hugo on shelves,” says Sarah Arnold, marketing and communications manager for Parnassus Books in Nashville. What accounts for the miracle? BookTok.

The online landscape of “social read-ia” consists of vibrant communities on TikTok, Instagram, and beyond. Their collective enthusiasm sells books to the tune of tens of thousands of copies and millions of dollars. “Escapist genre fiction is the name of the game for a lot of trending titles. Spicy romance, expansive fantasy, page-turning mystery, and emotional fiction are all categories seeing exponential growth because of the #BookTok community,” observes Shannon DeVito, Director of Category Management at Barnes & Noble. The internet has mobilized fandom in ways that have rewired the music and film industries, and it’s no surprise that it’s reshaping books as well. This collision of one of our oldest cultural products with one of our newest technological advances has resulted in innovation, reinvention, and rediscovery in ways that no one—neither experts nor algorithms— predicted.

On platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter, readers are taking critical authority into their own hands to create new kinds of discourse and connection. Each platform works slightly differently, and, of course, the boundaries between them are permeable and ever-shifting. Katherine D. Morgan (@foreverabookseller) notes that “now, aspects of TikTok are taking over—look how reels are taking over Instagram! Instagram had its heyday, but now BookTok is taking over the world.” Though at least one influencer, Deedi (@deedireads), still prefers Instagram: In addition to the memes and reading challenges that thrive across platforms, “Bookstagram has deeper reviews, group-chat book-club-style discussions, and more conversation overall. For that reason, I think there’s more room for genres like literary fiction and nonfiction to thrive on Bookstagram.” Arnold agrees, suggesting that “Bookstagram seems to feature more literary fiction, memoirs, and social justice books than BookTok, whereas BookTok created such a community for those who have been implicitly or explicitly told that their taste in books isn’t ‘mature enough’ or is too nerdy.” Laynie Rose Rizer, BookTokker (@thelaynierose) and assistant store manager for East City Bookshop, says, “Where BookTok thrives is around diverse books about joy and love.”

Some influential readers are also pivoting from one platform or style of content to the other: Lupita Aquino (@lupita.reads) says that her growth on TikTok rapidly matched her established Instagram following, and because of the range and depth of her commentary there, she’s been tapped to judge literary awards and run her local bookstore’s book club: “I never anticipated moving toward TikTok, because I initially thought a lot of its content was silly. I didn’t take it seriously as a platform where one could (or would) really engage in discussions. I was absolutely wrong.” Bookstagram is known for its aesthetic curation: the well-lit #TBR (To Be Read) stack, the color-coded shelfie, and the artfully arranged “flatlay” tableau. But, as BookTokker Kevin Norman (@kevintnorman) observes, “With TikTok, anyone can be a content creator. You don’t need perfect edits, filters, or a following to make sure you reach an audience.” Freed from certain expectations of “curation,” creators are free to share the books that move them in ways that diverge from current sales pushes, and create new trends in their wake.

But BookTok’s advantage isn’t just breadth; the algorithm of the For You Page allows for a lot of specialization, and increasingly specific subcultures emerge around niche interests and themes. Norman notes, “BookTok can reach a wider audience than any other social media platform, and it is amazing at separating us into niches. You can find a pocket of the platform for any genre you might be interested in.” The impact of these social media conversations isn’t just on how we talk about books; BookTok is fundamentally shifting which books get to grow under the glow of public attention at all. These platforms mobilize #OwnVoices communities in ways that publishers have to take seriously. Rizer explains that social media shows publishers that “they have the sales to back it up, that readers of color, LGBTQ+, neurodivergent, and disabled readers exist and would love to see themselves represented in the books they’re reading.” This is a common sentiment; says Arnold, “I hope these platforms offer space for every niche to be represented. They’re groups of people who deserve to have their stories told! Queer voices, indigenous voices, voices of color—they’re all voices people want to hear.”

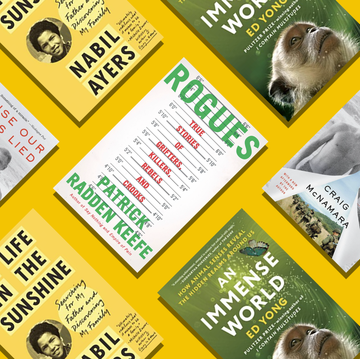

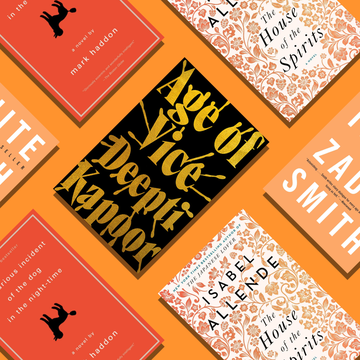

Because it’s driven by the personal interests and preferences of content creators, one person “rediscovering” an older or under-covered book can set off a cascade. Like Taylor Jenkins Reid, authors Adam Silvera (They Both Die at the End), Colleen Hoover (It Ends with Us), and Madeline Miller (The Song of Achilles) have seen sales of their older titles buoyed by unpredicted waves of interest brought about by “rediscovery” in certain virtual circles. DeVito notes, “#BookTok has been instrumental in elevating backlist books. Authors who have had books out for years are now selling thousands of copies per week.” It’s great to see backlist books getting this kind of attention, particularly in marginalized circles. The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo was rediscovered and reclaimed because many queer bookstagrammers identified and emphasized the book’s sapphic plot line, a twist that hadn’t initially been spotlighted.

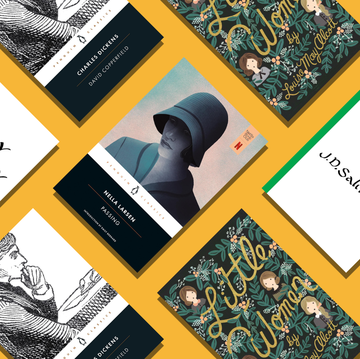

This effect goes beyond recent backlist—much older books are finding new fans and starting new conversations as well, thanks to the momentum of social media. Bookstagrammer Rod Kelly (@read_by_rodkelly) proudly declares, “We don’t read the same books,” convincing reluctant readers to give writers like Philip Roth a chance. Others are digging even further back, resurfacing books from almost a century ago. Bookstagrammer Hunter Mclendon (@shelfbyshelf) has begun a project reading every winner of the National Book Award for Fiction in addition to his #tbr stack, crowded with the latest trendy upcoming releases, and has been documenting his journey on his platform. “I find that if I can convince two or three people to pick up the book and post about it, eventually it’ll catch on,” he says. “Backlist titles keep catching the wave because people love to discuss their favorites with new readers.”

On social media, word of mouth is handed a megaphone: Here, voice and personality dominate. Megan Tripp, who is both a social media manager handling influencer marketing outreach for Penguin Random House and a bookstagrammer herself (@booksnblazers), observes how “content creators have so much more freedom to put all of their personalities into content, whereas obviously publishers and brands are more constricted by their business practices.” Rizer also notes that “publishers put a lot of effort into marketing books with their ads and influencer programs for a book that I'll barely see on my For You Page, and then I’ll see a book blow up purely on the strength of the unpaid content creators who loved it.” Publishers themselves are not the real movers and shakers of these social media spaces. Brand accounts are cropping up on TikTok now, but their engagement is lower, and they’re hopping onto trends rather than initiating them. However, Tripp continues, “that doesn’t mean that publishers’ content can’t be driven by personalities—in fact, publishers are tending to lean toward that now.” Prestige imprints like Riverhead Books are contracting with influencer personalities and letting them take over accounts with more centralized creative control.

Part of the popularity of BookTok may also have something to do with diminishing outlets for criticism. Books coverage across the board is getting cut; in one year of working as a book publicist, more than 75 contacts (outlets ranging from newspapers and glossy magazines to trendy digital media sources) were removed from my pitch rotation due to closure and turnover. The boom of book-related content and commentary on social media exists as a counterpoint to the state of literary conversation in legacy media. “In addition to getting book recommendations from new articles and morning shows, people are getting suggestions from content creators who look like them, who love like them, who share similar life experiences,” Rizer says. “I’m able to get LGBTQ+ book recs from people in my own community whose opinion I trust.”

“#BookTok is an amazing opportunity for booksellers and the book community as a whole,” DeVito says. After all, it’s at the cash register that bookstores see this social media momentum reaching out of our screens and into real life. DeVito cites how Barnes & Noble has created displays around viral titles and trends, and that the interest in these titles has also provided other booksellers a means for hand-selling other similar titles deserving of closer attention. Powell’s Book's Katherine D. Morgan says, “Along with being a bookstagrammer and writer myself, as a bookseller it’s interesting to see what people are connecting with and how they’re connecting with it.” She adds, “Before this year, I saw Colleen Hoover books selling now and again, but in the past couple weeks I’ve seen her books, or titles like The Love Hypothesis, by Ali Hazelwood, flying off shelves. I see it in what people are asking for, and what they bring up to the cash register. I’ve been a bookseller since 2017, and I don’t think I’ve seen social media this impactful since Instagram launched Rupi Kaur’s Milk and Honey.”

The rise of BookTok and other literary social media comes down to the feeling of trust between content creators and their followers. DeVito observes, “We seem to be in the midst of a reading renaissance, and people are either rediscovering their love of reading or finding it for the very first time.” In these spaces, influencers are supplementing the roles of critics and reviewers while building communities, offering alternatives to legacy media’s traditional books coverage, and uplifting titles deserving of deeper attention that might not otherwise have received it. It’s democratizing, it’s energizing, and it’s powerfully disruptive at a time when the book industry needed a reinvigorating shift. Hunter Mclendon says it best: The power of the literary internet is that “any book can receive attention if someone puts the right energy behind it.”