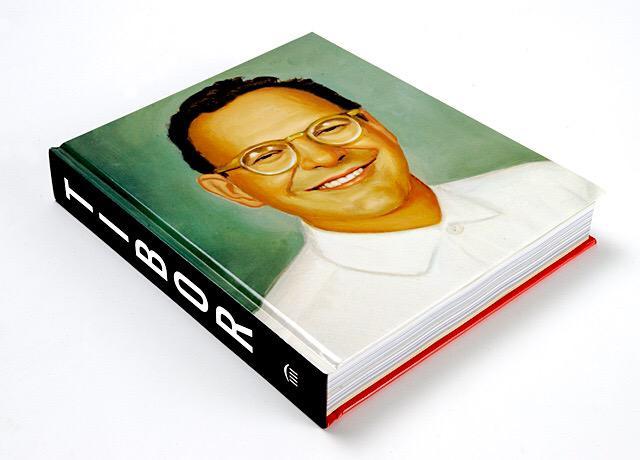

10 lessons from designer Tibor Kalman: Perverse Optimist

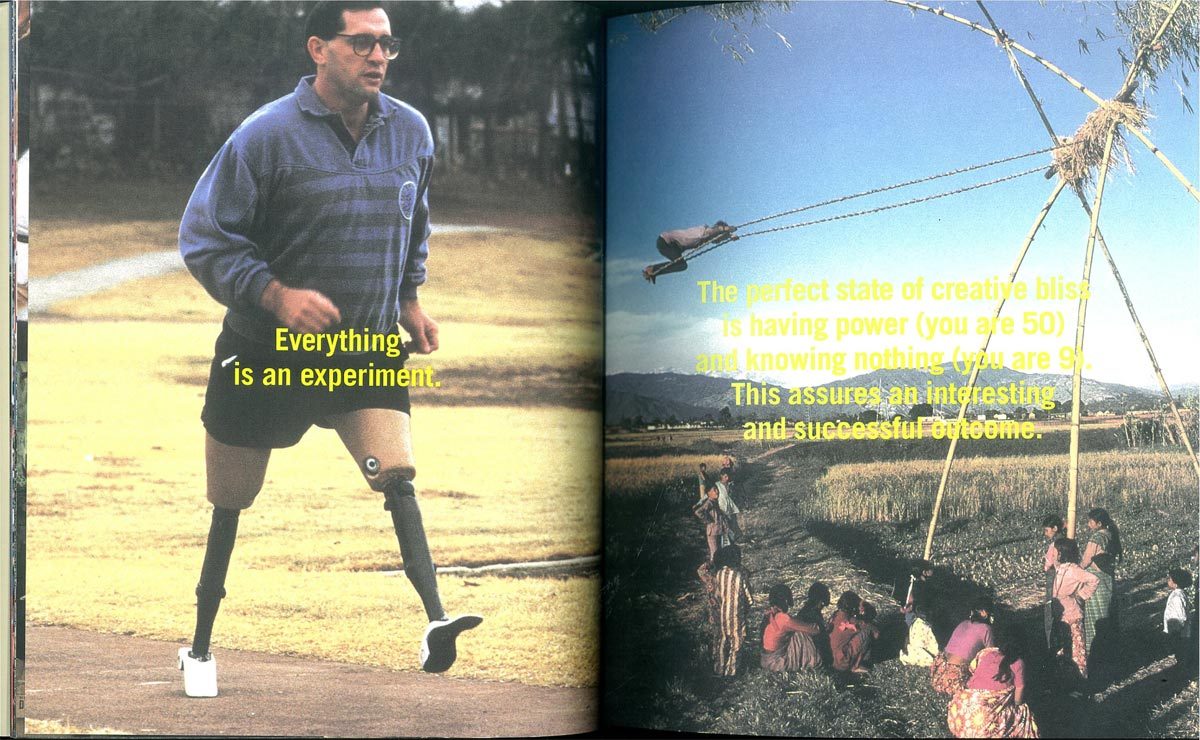

1. Everything is an experiment.

You can get a great feel for what Tibor Kalman (1949–1999) was about just from the opening pages of Tibor Kalman: Perverse Optimist…

2. Learn on the job.

Peter Hall points out that Tibor was always “learning on the job—or, as someone side of the journalistic vocation, conducting an education in public.”

One way he did that was to hire young designers more talented than him and learn from them:

That was the way I learned. I stood over their shoulders, and learned how graphic design is done. But I was always the boss. It has been a curious phenomenon in my life that I’ve continued pretty much throughout my career; I would try to get the job I couldn’t get, and not know how to do it, and then I would hire people who did know how to do it, and I would direct them. That to me is always the ideal way to work, because you learn very quickly and you have the means to do something, and yet you know nothing about the field, so you can do something original.

3. As soon as you learn how to do something, move on.

I did two of a number of things. The first one, you fuck it up in an interesting way; the second one, you get it right; and then you’re out of there… I think as long as I don’t know how to do something, I can do it well; and as soon as I have learned how to do something, I will do it less well, because it will be more obvious. I think that goes for most people. I think most people spend too much time doing one thing.

4. Having a style is a kind of death.

David Byrne, for whom Kalman designed many album covers, including Remain In Light:

Tibor and company don’t have a signature style, and that is a worthy ambition in life…. Having a recognizable style relegates you to the status of quotable icon. And while being an icon is flattering, I imagine, once it happens, you become irrelevent.

My own ambition is to write a song that sounds like I stole it—like “I” didn’t write it, but it has always been there. To get the “I” out of the song is the ultimate compositional coup, whether in music or design.

5. Visual literacy isn’t enough. Designers have to read everything.

Kalman said that “an enormous amount of graphic design is made by people who look at pictures but don’t know how to think about them.”

I started asking job candidates, “What have you read in the last year?” Because I suddenly began to realize that the difference between a good and a bad designer is how much did they know about everything else—biology, history. Because graphic design is just a means of communication, a language, and what you choose to communicate, and how and why on a particular project, that is all the interesting stuff.

6. You don’t necessarily have to be visually motivated to be a designer.

Rick Poynor on Kalman’s red-green colorblindness (I have it, too):

Most designers are designers because of an exceptional intensity in their response to visual form coupled with a degree of talent for manipulating it. Kalman is unusual among those who choose design as a profession in not being a visually motivated person in this sense. He is red-green color blind and, although this is not severe, it means that he treats color as an “idea” rather than as a sensation to which he responds according to intuition or taste. He will know intellectually that “sky blue” is called for to get an effect he wants to achieve without being able to specify for himself which shade of blue it should be.

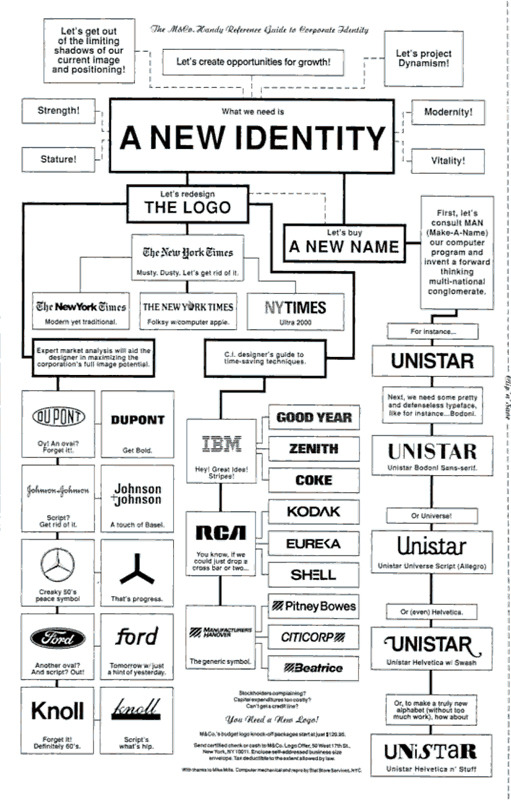

7. Don’t steal the style, steal the thinking behind the style.

Kalman said it was okay to borrow ideas, but “transform” is the key word: you have to know the context of the ideas and not de-contextualize them, but re-contextualize them:

Reference means just that: You refer to something. It gives you an idea. You create something new.

Real modernism is filled with historical reference and allusion. And in some of the best design today, historical references are used very eloquently. But those examples were produced with an interest in re-contextualizing sources rather than de-contextualizing them.

There’s an important difference between making an allusion and doing a knock-off. Good historicism is… an investigation of the strategies, procedures, methods, routes, theories, tactics, schemes, and modes through which people have worked creatively…. We need to learn from and interrogate our past, not endlessly repeat its recipes.

8. Photographs are neither true nor false.

Early in the history of photography models were used to enact situations for a camera to record. Later, we learned how to retouch images, first by hand, later by rearranging the tiny dots that make up the images. Meanwhile, there has always been the cheapest and easiest way of making photographs lie—simply changing the caption to change the meaning of the image. Some people accept this but still argue the photograph remains in some way uniquely “honest.” They say that for it to exist, some kind of real-life situation also had to exist. They claim that the fact that a camera can be set up by remote control to record whatever passes in front of it somehow confers objectivity. They cling to the idea that the photograph is an inherently “real” or honest image and as such is always on a different plan from an obviously subjective form of visual communication, such as painting. However, I believe that photography is just like painting and that it can lie just as effectively. I do not accept that there is necessarily a “true” moment that the camera captures, because that moment can be manipulated as much as anything else.

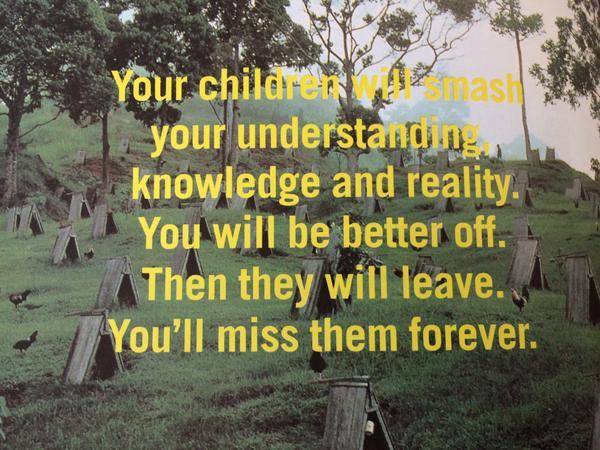

9. Children give you new ways of looking at things.

We chose to increase the complexity of our lives by having children. The greatest benefit of having those children has been to look at the world through their eyes and to understand their level of curiosity and to learn things the way they learn things.

10. Marry well.

At first, I only new Tibor Kalman as Maira Kalman’s late husband. Isaac Mizrahi might argue that’s as it should be:

Tibor’s most brilliant contribution was to marry Maira. If he hadn’t, I would have. I don’t mean to sound corny and romantic, just that his relationship with her is a work of art. She has an incredible in-born ability to be a touchstone, and pick out what’s good in a room, whether it’s a screenplay, a piece of music, or a piece of furniture. I never think of them seperately, or, his sense of humor or her sense of humor, I think about them together, how much he owes to her and she owes to him.

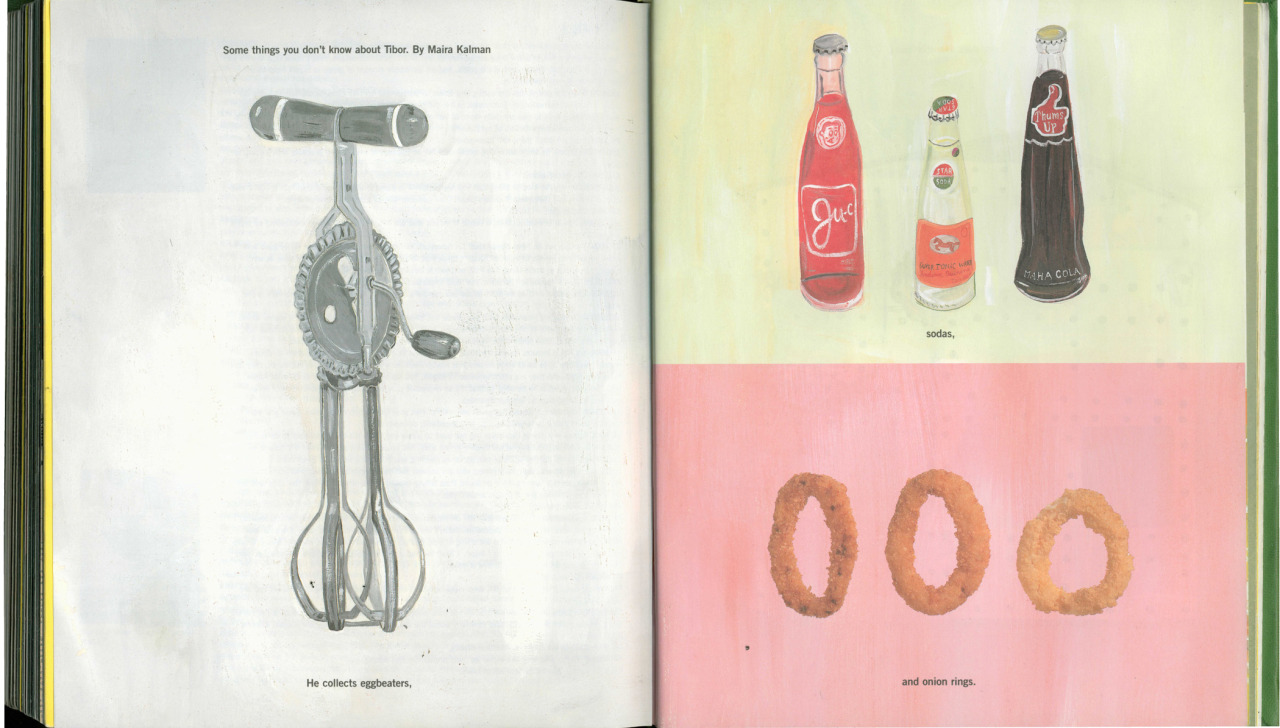

Maira Kalman painted the closing pages of the book:

It’s out-of-print and can be a little hard to get your hands on, but anyone interested in design should give Tibor Kalman: Perverse Optimist a read.

Filed under: my reading year 2015

betzistar

betzistar