Abstract

Social media, one of the most pervasive forms of technology, has been widely studied in relation to the mental health and well-being of individuals. However, the current literature on social media and well-being has provided mixed and inconclusive findings, thus creating a polarizing view of social media. These mixed findings continue to extend into the pandemic, with researchers debating over the effects of social media in the new norms of social isolation. In light of these inconclusive findings, the aim of our meta-analysis was to synthesize previous research data in order to have a holistic understanding of the association between social media and well-being, particularly in the present context of COVID-19. The current meta-analysis systematically investigated 155 effect sizes from 42 samples drawn from 38 studies published during the COVID-19 pandemic (N = 43,387) and examined the potential moderators in the relationship between social media and well-being, such as the different operationalizations of social media usage and demographics. Overall, our study found that the relationship between social media usage and well-being was not significant in the context of COVID-19. Additionally, the impact of various moderators on the relationship between social media and well-being was found to vary. We discuss the various theoretical, methodological and practical implications of these findings and highlight areas where further research is necessary to shed light on the complex and nuanced relationship between social media and well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Since its inception in the 1990s, social media has been adopted by more than half of the 7.7 billion people in the world, and the number is projected to continue increasing (GlobalWebIndex, 2015; Pew Research Center, 2021; Statista Research Department, 2021b). Indeed, in the last decade alone, social media platforms have almost tripled their total user base, from 970 million in 2010 to more than 4.72 billion users in 2021 (GlobalWebIndex, 2015; Kemp, 2021; Pew Research Center, 2021; Statista Research Department, 2020). Social media, which was traditionally only used as a simple communication platform, has now evolved into a crucial platform for the creation and transmission of user-generated content, amongst various other uses (Hunter, 2020; Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010; Kim & Johnson, 2016; Lardo et al., 2017). In light of its pervasiveness throughout society, laypersons and researchers alike have taken an interest in the psychological effects of social media (David et al., 2018; Perloff, 2014; Saiphoo & Vahedi, 2019; Vogel et al., 2015).

In particular, one psychological implication of social media that has been widely studied is related to the mental health and well-being of individuals. Researchers have extensively covered the implications of social media on well-being, with many cross-sectional and correlational trend analyses finding a negative correlation between social media usage and well-being (Brunborg & Andreas, 2019; Ivie et al., 2020; Keles, et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2016; McPherson et al., 2006; Milani et al., 2009; Park et al., 2014). Interestingly, many meta-analytic studies on the relationship between social media usage and depressive symptoms reported small but significant effect sizes of r = 0.11 (Cunningham et al., 2021), r = 0.11 (Ivie et al., 2020) and r = 0.17 (Vahedi & Zannella, 2021) respectively. This suggests that the effect sizes are typically small but still significantly predict lower well-being. Indeed, recent meta-analytic studies have also reported that higher levels of social media usage were associated with lower psychological well-being (Huang, 2017), decreased self-esteem (Liu & Baumeister, 2016), increased loneliness (Song et al., 2014), as well as an increase in depressive symptoms (Cunningham et al., 2021; Ivie et al., 2020). Against this backdrop of a possible link between social media and depressive symptoms, researchers have even coined the term “Facebook depression” as a consequence of social media usage (O'Keeffe & Clarke-Pearson, 2011), further cementing the negative psychological impacts of social media on well-being.

Several lines of reasoning and empirical evidence have been presented to explain why social media usage is associated with lower well-being. One explanation is that the strength of relationships forged through social media might be weaker due to lower quality conversations that lack depth (Kraut et al., 1998; Lee, 2009). This is because communication on social media takes place online, thus lacking the necessary human touch and quality needed to provide the same benefits as real-life interactions (Christensen, 2018; Lee et al., 2011; Reich et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014). Indeed, studies have shown that face-to-face interactions with family and friends are associated with higher well-being (Adams et al., 2011; Sullivan, 1953) whereas communication via social media is associated with lower levels of well-being (Hunt et al., 2018; Lee, 2009; Newson et al., 2021). Additionally, researchers have also posited that social media might cause individuals to experience reduced social interaction (Hunt et al., 2018; Neto et al., 2015). This is also known as the “displacement hypothesis”, whereby increased time spent using social media reduces the time available for real-life interactions (Dunbar, 2016; Kraut et al., 1998). This view has been supported by several studies that have found a positive association between social media usage and loneliness (Hunt et al., 2018; Neto et al., 2015). Others argue that social media platforms (e.g., Instagram, Facebook) provide ample opportunities for peer comparison about self-presentation and image among individuals (Mascheroni et al., 2015). The facilitation of upward social comparison through social media can increase the psychological distress of individuals and result in stress, anxiety and lower levels of self-esteem (Chen & Lee, 2013; Feinstein et al., 2013; Fox & Vendemia, 2016). Lastly, other studies have also found that social media adversely affects well-being due to the high exposure of negative stimuli and experience such as derogatory content, cyberbullying, and unhealthy social comparison (Vogel et al., 2014; Whittaker & Kowalski, 2015).

Despite the seemingly negative implications of social media, a smaller body of research has also shown that social media usage is associated with higher well-being (Bucci et al., 2019; Ellison et al., 2007; Stern, 2008; Naslund et al., 2016). For instance, the social compensation hypothesis posits that online communication will benefit people who are socially anxious and isolated as they may feel more at ease when developing friendships online in a safe environment (Barker, 2009; Ellison et al., 2007; Zywica & Danowski, 2008). Another line of argument stems from the stimulation hypothesis, which posits that online communication stimulates communication with existing friends, leading to mostly positive outcomes and stronger friendships overall (Nesi et al., 2018; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). Indeed, studies have reported that social media usage was associated with an increase in social capital which is linked to positive psychological effects (Chan, 2015; Chen & Li, 2017; Nieminen et al., 2010). Consistent with this, an increase in self-disclosure, communication and friending via social media was also found to have a positive effect on psychological well-being (Chen & Li, 2017). Other studies also found that social media usage was associated with a higher quality of friendship (Ellison et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2019) and social support (Bucci et al., 2019; Naslund et al., 2016), which are both related to higher levels of well-being (Asante, 2012; Chu et al., 2010; Cuadros & Berger, 2016).

Taken together, the association between social media and well-being still remains a polarizing issue due to the mixed findings of both positive and negative correlations. Several explanations have been hypothesized to explain the mixed findings regarding the link between social media and well-being. One of the plausible theories attributes the mixed findings to the duality of social media ― the freedom of expression and different functionalities on social media can create a myriad of potential harm and benefits to an individual (Baccarella et al., 2018; Pavlíček, 2013). Indeed, one researcher coined it “the social media see-saw” (Weinstein, 2018) suggesting that it is a balancing act between both positive and negative impacts of using social media and that social media does not consist of only one of these effects. Another reason for the mixed findings could be due to the different operationalizations of social media. For example, some studies operationalized social media usage as a coping mechanism (Eden et al., 2020; Teresa et al., 2021) while others did not (Alam et al., 2021; Riehm et al., 2020). Moreover, many studies utilised subjective and self-report measures instead of objective measures which might be a better indicator of social media usage (McCain & Campbell, 2018). Additionally, different studies also measured social media usage differently (i.e., number of times an individual checks their phone versus total time spent on using their phone). Indeed, the variation in operationalizations and methodologies across the present literature has made it difficult to reach a conclusion whether social media usage is positive or negative for an individual.

While there has been extensive research on the topic of social media and well-being, the recent development of the COVID-19 pandemic has warranted a need to investigate how the dynamics of the relationship between social media and well-being has changed, as well as the potential benefits and detrimental effects of utilising social media during COVID-19. During this pandemic, staying at home has become the norm for individuals around the world (Engle et al., 2020). This period of social isolation has accelerated the rate of social media adoption which can be observed through the engagement and growth rates of social media around the world. For example, Tik Tok’s annual user growth rate in the US was 85.3% in 2020 alone (Statista Research Department, 2021a). Furthermore, the average time spent on social media by US users in 2020 also grew from 54 to 65 min per day (Statista Research Department, 2020).

The global increase in social media usage during COVID-19 has been commonly attributed to the increasing reliance on social media as a form of coping against loneliness (Cauberghe et al., 2021). Several studies have shown that the pandemic has resulted in an increase in loneliness due to self-isolation and social distancing (Groarke et al., 2020; Killgore et al., 2020) and people are trying to find different ways of coping with it. As mentioned earlier, research conducted before the pandemic found that social media usage is associated with multiple benefits including increases in social capital and social support (Chen & Li, 2017; Wang et al., 2019). Consistent with this, studies conducted during the pandemic have reported that higher social media usage is negatively correlated with loneliness (Groarke et al., 2020). Therefore, people might be increasing their tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism against loneliness, which instead could make social media a potential protective factor that enables individuals to obtain the interaction and social support that they seek during the pandemic. Thus, we hypothesize that there will be a positive correlation between social media and well-being in the context of COVID-19. Additionally, we hypothesize that the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism will be positively correlated with higher levels of well-being.

Considering the high prevalence of social media, as well as the increased reliance on social media to cope with social isolation due to COVID-19, there is a need to re-investigate the link between social media and well-being. Although some research has been conducted in the context of COVID-19, many of those studies had mixed results (Fumagalli et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2020; Masciantonio et al., 2021). Therefore, there exists a need for a meta-analysis to test the conflicting hypotheses about the relationship between social media and well-being. A meta-analytic study can additionally provide the grounds for examining the potential moderators such as different operationalizations of social media and well-being. Additionally, the current meta-analysis aims to shed light on the individual differences in the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism. Through the synthesis of previous research findings, we will be able to have a clearer picture of the potential boundary conditions of the harms and benefits of social media on well-being in the context of COVID-19.

Method

Search strategy

The present meta-analysis focused on synthesizing findings on the association between social media and well-being in the context of COVID-19. Social media provides an online platform with multiple functionalities (e.g., communication, entertainment, media sharing) that may have an impact on the mental health of individuals. Therefore, the search strategy involved the review of the multiple measures of social media and their various impacts on different aspects of well-being. With that, a literature search was conducted in EBSCOhost ERIC, EBSCOhost PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science using the following keywords: ("Social Media" OR "Online Friend" OR "Online Friends" OR "Social Network" OR "Social Networking Sites" OR "Social Media Technology" OR "Online Community" OR Facebook OR Twitter OR Blog* OR Youtube OR Tumblr OR Discord OR Reddit OR Instagram OR Tiktok OR Snapchat OR Pinterest OR LinkedIn OR "Chat Room*" OR "Online Forum*") AND ("wellbeing" OR "well-being" OR "well being" OR "mental health" OR satisfaction OR happiness OR happy OR "positive affect" OR "negative affect" OR mood OR anxiet* OR anxious OR sadness OR "Cantril Ladder" OR lonel* OR self-esteem OR self-efficacy OR depress* OR self-worth OR "quality of life") AND (COVID-19 OR COVID19 OR "corona virus" OR coronavirus OR 2019-nCov OR SARS-CoV-2). Databases were searched for all reports available by June 2021.

Furthermore, we conducted manual searches using the keywords “social media” AND COVID-19 in journals related to computers and new media, mental wellness, and mental disorders, namely: (1) Computers in Human Behaviour, (2) Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, (3) Journal of Affective Disorders, (4) Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, (5) Journal of Mental Health, (6) New Media & Society, and (7) Social Indicators Research. To capture unpublished literature, manual searches were also conducted in ProQuest Dissertations & Theses and Google Scholar using the same keywords "social media" AND COVID-19.

Inclusion criteria

In total, the search resulted in 2591 potentially eligible records. After removing duplicates using the Mendeley Desktop version 1.19.4 (Mendeley, n.d.), a total of 1704 records were screened for inclusion based on titles and abstracts independently by the first and second author who then discussed and resolved discrepancies. Agreement between the two authors was good, with an average of 98.00% for the abstract screening stage. Based on abstracts, 592 irrelevant records were removed, leaving 1112 full-text records to be screened for inclusion based on the following criteria:

-

1.

Studies were included if they provided quantitative data and specified that the study was conducted during COVID-19), regardless of other methodological characteristics. Studies were also included regardless of their peer review status. Only the peer-reviewed version was kept if two versions of the same study were available (e.g., as part of a thesis and as part of a journal article). There were no restrictions on any sample characteristics such as age or gender.

-

2.

Studies were included as long as they subjectively or objectively measured and reported social media usage (i.e., duration of social media usage, number of times social media was accessed, frequency of social media usage). Subjective measures could be single- or multiple-item self-reports assessing any form of social media usage, while objective measures included screenshots of screen time usage or time spent on social media.

-

3.

Studies were included if they reported at least one measure of well-being. Well-being represents the presence of indicators of psychological adjustment such as life satisfaction or positive affect, and the absence of indicators of psychological maladjustment such as negative affect, or depression (Hartanto et al., 2021a, b; Houben et al., 2015). Common measures of well-being include, but are not limited to, the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985), the General Anxiety Disorder Scale (Spitzer et al., 2006), the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2003), and the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, 1996).

-

4.

Studies were included if the information necessary to compute effect sizes were reported. If a study was eligible but did not report the appropriate statistics, the original authors of the study were contacted directly to obtain usable data. Out of the 37 authors contacted, 15 authors provided the requested data. The remaining 22 did not respond despite three repeated requests.

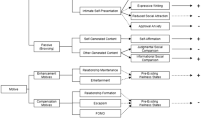

Based on the examination of the potentially eligible full-text records, 38 records (38 studies) met all criteria and had sufficient data to compute effect sizes (Al-Qahtani et al., 2020; Alam et al., 2021; Aymerich-Franch, 2020; Bonsaksen et al., 2021; Boursier et al., 2020; Chakraborty et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021a; Chen et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021b; Chen et al., 2021c; Clavier et al., 2020; Cuara, 2020; Drouin et al., 2020; Eden et al., 2020; Ellis et al., 2020; Fernandes et al., 2020; Fumagalli et al., 2021; Hammad et al., 2021; Hikmah et al., 2020; Ikizer et al., 2021; Krause et al., 2021; Krendl et al., 2021; Lake, 2020; Lemenager et al., 2021; Lisitsa et al., 2020; Magson et al., 2021; Masciantonio et al., 2021; Patabendige et al., n.d.; Reiss et al., 2020; Rens et al., 2021; Riehm et al., 2020; Şentürk et al., 2021; Sewall et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2020; Teresa et al., 2021; Wheaton et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021; Zhao & Zhou, 2021). 34 studies (89.47%) contributed one sample each, with the remaining 4 studies contributing multiple samples each, providing a total of 42 independent samples with a total unique N of 43,387 (Mdn = 603, M = 1058.22, SD = 1220.59, range = 46–6329). Based on available reports, the range of the mean age of the samples was 10.32–75.2 years (Mdn = 31.70, M = 28.98, SD = 13.29) with a median gender proportion of 67.70% female (M = 65.74%, SD = 15.17%). All eligible studies were conducted from 2020 to 2021, in 26 countries across five continents. The overall selection process of the studies to be included in this meta-analysis is demonstrated in the PRISMA flowchart in Fig. 1 (Moher et al., 2009).

Data extraction

The entire coding process was completed independently by the first and second authors who then discussed and resolved discrepancies after the initial coding process. Agreement was generally good, with an average of 99% (ranging from 98 to 100%) agreement between the two authors (see Table 1).

Firstly, we coded the zero-order Pearson correlation r or unadjusted odds ratio (OR) quantifying the association between social media usage and well-being. Thereafter, the following study characteristics were also coded: (a) publication source of the record (journal articles, unpublished data, dissertations, thesis, book chapters), and (b) country where the study was conducted. Additionally, the following demographic characteristics were coded: (a) the proportion of the sample which was female, and (b) the age range and mean age of the sample. Furthermore, we coded (a) the type of well-being that was assessed (e.g., loneliness, stress), (b) the exact measure used to assess well-being (e.g. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [PANAS], Generalized Anxiety Disorder [GAD], Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale [DASS-21]), (c) the social media platform used (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), (d) the mean number of times social media was accessed per day, and (e) the mean time spent on social media in hours per day. Lastly, we also coded for possible moderators such as (a) the source where the sample was retrieved from (community, schools, hospitals) and (b) whether studies measured the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism. For moderators which were not reported in the results section (e.g., FOMO, social media addiction), this was because there was insufficient data reported in the included studies to conduct an analysis.

Meta-analytic approach

The main effect size index used was Pearson’s correlation coefficient r, which summarizes the strength of the bivariate relationship between two quantitative variables and is a measure of linear correlation between two sets of data (Allen, 2017). We also investigated overall differences in well-being scores between the groups with social media usage and without social media usage. Thus, another index we used was the OR, which provides an estimate for the relationship between two binary variables (Bland & Altman, 2000). Lastly, we converted OR effect sizes to r so that we could combine all the effect sizes. Effect sizes were coded or otherwise calculated such that positive values indicated an effect consistent with the hypothesis that individuals with higher social media usage will have higher overall well-being scores as compared to individuals with lower social media usage.

With some samples completing multiple measures of well-being, it was possible for samples to contribute multiple effect sizes, therefore violating the assumption of independent effect sizes in a meta-analysis. As a result, the overall meta-analytic effect sizes were computed using a four-level meta-analytic approach (Pastor & Lazowski, 2018), with each individual effect size nested within the sample it was retrieved from, which was further nested within the study it was part of.

Transparency and openness

This meta-analysis’s design and analysis plan were not pre-registered. All data used in the current work has been made publicly available on Researchbox (#683). All analyses were conducted in R version 4.1.1 (R Core Team, 2020) using the meta-analytic package metafor version 3.0–2 (Viechtbauer, 2010) and the package psych version 2.1.3 (Revelle, 2022).

Results

Overall effect size

Two overall meta-analytic effect sizes were calculated. All of the included studies utilised a between-subjects design. The first was calculated in terms of the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism and well-being scores. The second was calculated in terms of overall social media usage and well-being scores. The two different operationalizations (i.e., actual social media usage versus the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism) may have a different effect on well-being and thus lead to different associations between social media and well-being. Therefore, it is important to separate the two so that we can have an accurate understanding of the relationship between normal social media usage and well-being, as well as the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism and well-being. The first effect size was calculated from 5 studies contributing a total of 5 samples and 72 effect sizes. The result suggests that the overall effect size was small, and that individuals with higher tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism had significantly lower well-being as compared to individuals with a lower tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism (transformed r = -0.06, Fisher’s z = -0.06, SEz = 0.02, 95% CIz = [-0.10, -0.02], p = 0.001).

The second effect size was calculated from 33 studies contributing a total of 37 samples and 83 effect sizes, with the exclusion of the 5 studies which measured the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism. These 5 studies were excluded to differentiate actual social media usage with the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism. The result suggests that there was no significant association between social media usage and well-being (transformed r = -0.06, Fisher’s z = -0.06, SEz = 0.03, 95% CIz = [-0.13, 0.001], p = 0.055).

Methodological moderator analyses

Operationalization of social media usage

We found that the association between social media usage and well-being was small in magnitude and non-significant regardless of the operationalization of social media usage (ps ≥ 0.079; see Table 2). The association between social media usage and well-being was non-significant when social media usage was operationalized as overall time spent on social media and when operationalized as the number of times social media was accessed.

Study quality

The effect sizes (145 effect sizes from 37 samples and 34 studies) from peer-reviewed journal articles (95% CI = [-0.14, -0.01]) were not significantly different from the effect sizes (10 effect sizes from 5 samples and 4 studies) from unpublished theses, preprints and dissertations (95% CI = [-0.11, 0.17]) given the overlapped 95% CIs. The results suggest that peer review status was not a significant moderator at least in the current study.

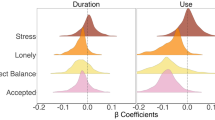

Operationalization of well-being

We found that regardless of how well-being was operationalized, the association between social media usage and well-being association was small in magnitude (see Fig. 2). Evidence from comparing the 95% CIs obtained suggests that none of the operationalizations of well-being produces social media-well-being relationships that are statistically different from each other (see Fig. 2).

Summary forest plots for operationalizations of well-being. Note. n = number of studies, m = number of samples, k = number of effect sizes. Numbers on the right indicate estimates of meta-analytic effect size in the form of Fisher’s z and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Squares represent estimates of meta-analytic effect size in the form of Fisher’s z, with the size of each square representing total sample size. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals. All outcomes were coded such that positive effect sizes indicate higher levels of well-being for groups with higher social media usage

Sample analyses

Demographic factors

Table 2 provides a summary of moderator analyses (using all of the 38 studies where data was available) with reference to various demographic factors. Subgroup analyses found that the association between social media usage and well-being was small but significant for samples recruited from the community (number of studies = 25, number of samples = 27, number of effect sizes = 113, transformed r = -0.08, Fisher’s z = -0.08, SEz = 0.03, 95% CIz = [-0.15, -0.01], p = 0.016), but not for samples recruited from schools and mixed sources (ps ≥ 0.861; see Table 3). However, moderation analyses did not find age, gender, and sample source to be significant moderators, as evidenced by the overlapping 95% CIs of the categorical variables.

Publication bias

To rule out potential threats to the validity of the meta-analysis due to small-study effects and selective reporting, we ran Egger’s test (Egger et al., 1997) for publication bias (Sterne & Egger, 2001). A statistically significant p-value (p < 0.05) obtained from Egger’s test would indicate that publication bias was present in the included data. Upon conducting Egger’s test for publication bias, we found that b = 17.88, SEb = 6.59, 95% CIb = [4.97, 30.79], p = 0.007 for the relation between social media usage and well-being, suggesting that publication bias was present in the current meta-analysis and skewed towards a negative effect size (see Fig. 3). This suggests that the negative association between social media usage and well-being found in our study might have a higher likelihood of being biased.

Discussion

The current literature on social media and well-being has provided mixed and inconclusive findings, thus creating a polarizing view of social media. These mixed findings continue to extend into the pandemic, with researchers debating over the effects of social media in the new norms of social isolation (e.g., quarantines, lockdowns, social distancing). In light of these inconclusive findings, the aim of our meta-analysis was to synthesize previous research data in order to have a holistic understanding of the association between social media and well-being, particularly in the present context of COVID-19. Furthermore, we also considered the effects of various moderators—such as demographics, as well as different operationalizations of social media usage and well-being to potentially explain the mixed findings in the current literature. Overall, our results show that the relationship between social media and well-being was non-significant in the context of COVID-19 which is inconsistent with the majority of the current findings that social media is linked to poorer psychological outcomes.

The lack of association found in our study does not support our initial hypothesis of a positive correlation between social media usage and well-being in the context of COVID-19. Nevertheless, our results provide additional support suggesting that the relationship between social media and well-being is not measure-specific across different operationalizations. Indeed, the consistent results across all measures of well-being in our study is in line with past findings which have suggested that different operationalizations of well-being such as negative affectivity, anxiety and depression are highly related (Tanaka-Matsumi & Kameoka, 1986; Ryff, 1989; Sandvik et al., 2009). These results further supported the robustness of the current findings regarding the null effect in the association between social media usage and the different operationalizations of well-being. Similarly, our moderation analyses of demographic variables found that none of the moderators except community were significant. One possible reason for the nonsignificant findings could be due to social media usage being prevalent across the different demographics in our current society (GlobalWebIndex, 2015; Kemp, 2021; Pew Research Center, 2021; Statista Research Department, 2020). As a result of globalization and the rising adoption rate of technology, we speculated that social media usage has become the norm and individuals around the world tend to use social media for relatively similar amounts of time (GlobalWebIndex, 2015; Kemp, 2021; Pew Research Center, 2021; Statista Research Department, 2020). Therefore, this could explain why we did not see differences in effects across different demographic variables. Interestingly, community was the only significant moderator across all demographic variables. One possible reason could be that within the broader community, there might be more individuals who are depressed, lonely, or lack social interaction during COVID-19. These individuals with poorer levels of well-being could have had an over-reliance on social media, thus contributing to an overall negative correlation between social media usage and well-being. Future research should thus conduct more longitudinal studies to explore sample source as a moderator and ascertain directionality of the relationship between social media usage and well-being.

Futhermore, our nonsignificant results are contrary to previous meta-analytic findings which have found that social media is significantly correlated with lower levels of well-being and may harm users by exposing them to negative experiences such as unhealthy social comparisons and feelings of inferiority (Vogel et al., 2014; Whittaker & Kowalski, 2015). Additionally, the nonsignificant effect size between social media usage and well-being in our study was inconsistent with previous studies which reported an effect size of r = -0.22 (Marino et al., 2018) and r = -0.20 (Yang et al., 2019) respectively. Similarly, previous meta-analytic studies on the relationship between social media usage and depressive symptoms also reported an effect size of r = 0.11 (Cunningham et al., 2021), r = 0.11 (Ivie et al., 2020) and r = 0.17 (Vahedi & Zannella, 2021) respectively. One possible reason for this nonsignificant relationship could be because the data was collected during pandemic periods. During a pandemic, individuals might experience heightened levels of loneliness due to social isolation. In the context of COVID-19, it is physically impossible to have face-to-face interactions with friends, thus increasing the importance of social capital during COVID-19. One of the few ways that an individual can have meaningful social interactions and obtain social support might be through social media (Hartanto et al., 2020). This supports previous research findings of social media usage being associated with increases in social capital (Chan, 2015; Chen & Li, 2017; Nieminen et al., 2010) and social support (Bucci et al., 2019; Naslund et al., 2016), which are both related to higher levels of well-being (Asante, 2012; Chu et al., 2010; Cuadros & Berger, 2016). Indeed, during pandemic periods, social media might be a potential tool for individuals to obtain the social support and that comfort that they seek, therefore attenuating the negative correlation between social media usage and well-being.

Additionally, our study was also interested in exploring the individual differences in the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism. Contrary to our hypothesis, the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism was negatively correlated with higher levels of well-being, which suggests that individuals who have a higher tendency to use social media as a form of coping are more likely to experience poorer emotional well-being than individuals who have a lower tendency to use social media as a form of coping. One plausible explanation for this finding could be because social media might not be a healthy coping mechanism. Supporting this line of argument, past findings have shown that an over-reliance on social media as a coping mechanism against life’s stressors might lead to problematic social media use which is associated with lower levels of well-being (Worsley et al., 2018; Kırcaburun et al., 2019).

At first glance, the findings for our two hypotheses may appear to be contradictory. We found that during a pandemic, social media may serve as a communication channel for social support and comfort. At the same time, we also found that over-reliance on social media as a coping mechanism against life’s stressors might be problematic. However, it is important to note that relying on social media as a coping mechanism may only lead to negative outcomes when it is excessive (Marttila et al., 2021). During a pandemic, normal usage and reliance of social media in order to stay connected with one’s loved ones may reap positive benefits. Moreover, although our results may suggest that the tendency to use social media as a form of coping is harmful, it is important that we cannot rule out the possibility of reverse causation. For instance, the detrimental physical and psychological impacts arising from COVID-19 factors could have caused individuals to experience lower levels of well-being in general (Stanton et al., 2020). Individuals with poorer levels of well-being could have turned to social media as a form of coping, thus contributing to an overall negative correlation between the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism and well-being (Hartanto et al., 2021a, b; Song et al., 2014). For example, a previous meta-analysis studying the relationship between loneliness and Facebook usage found that loneliness led people to use Facebook more often (Song et al., 2014). The uncertainty regarding the directionality of the relationship between social media and well-being highlights the importance of longitudinal studies. Indeed, our meta-analysis found that most of the studies on social media usage and well-being were cross-sectional in nature. Therefore, future studies should consider employing longitudinal designs to ascertain the directionality of the relationship.

Taken together, our study observes that there was a negative but non-significant correlation between social media and well-being during pandemic times. Our non-significant finding contributes to the present literature by suggesting that the relationship between social media and well-being is dynamic and dependent on different contextual factors. Furthermore, our study has identified several contextual factors whereby social media can be used as a potential avenue of support for dealing with pandemic-related stressors. During a pandemic whereby face-to-face interaction is difficult, social media may serve as a communication channel to provide social support and comfort (Chan, 2015; Chen & Li, 2017; Nieminen et al., 2010). Additionally, we found a negative association between the tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism and well-being, which is line with the present literature (Kırcaburun et al., 2019; Worsley et al., 2018). Moreover, our study also discovered several gaps in the current literature. Through our meta-analysis, we found that there was a lack of sufficient data to conduct analysis on many moderators (e.g., FoMO, problematic social media usage). This highlights the need for future researchers to look at different moderators when conducting studies on social media and well-being. Moreover, most of the studies on social media usage and well-being were cross-sectional in nature which highlights the importance of longitudinal studies to ascertain directionality. There were also great variations in the operationalizations of social media (i.e., tendency to use social media as a coping mechanism versus non-coping) and the methodologies of measuring social media usage (i.e., subjective versus objective measures, total time spent on social media versus number of times social media was accessed) across the studies included in our meta-analysis. Our meta-analysis thus highlights the need for a standardization of methodologies and operationalizations when conducting studies on social media usage.

However, our study has one important limitation: We found that publication bias was significant in our study which suggests that our findings might be biased. This highlights the importance of taking into account non-significant findings for future research. In sum, our meta-analysis can serve as an important guideline for future studies to improve its operationalization and methodological rigors as well as to shed light on the potential use of social media as an important avenue of social support during the pandemic.

Data availability

This meta-analysis’s design and analysis plan were not pre-registered. All data used in the current work has been made publicly available on Researchbox (#683).

References

References marked with an asterisk (*) indicate studies included in the review.

Adams, R. E., Santo, J. B., & Bukowski, W. M. (2011). The presence of a best friend buffers the effects of negative experiences. Developmental Psychology, 47(6), 1786–1791. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025401

*Alam, M. K., Ali, F. B., Banik, R., Yasmin, S., & Salma, N. (2021). Assessing the mental health condition of home-confined university level students of Bangladesh due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Health, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01542-w

Allen, M. (2017). The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. SAGE Publications.

*Al-Qahtani, A. M., Elgzar, W. T., & Ibrahim, H. A. F. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Psycho-social consequences during the social distancing period among Najran City population. Psychiatria Danubina, 32(2), 280–286. https://doi.org/10.24869/psyd.2020.280

Asante, K. O. (2012). Social support and the psychological wellbeing of people living with HIV/AIDS in Ghana. African Journal of Psychiatry, 15(5), 340–345. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v15i5.42

*Aymerich-Franch, L. (2020). COVID-19 lockdown: Impact on psychological well-being and relationship to habit and routine modifications [Preprint]. PsyArXiy. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/9vm7r

Baccarella, C. V., Wagner, T. F., Kietzmann, J. H., & McCarthy, I. P. (2018). Social media? It’s serious! Understanding the dark side of social media. European Management Journal, 36(4), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.07.002

Barker, V. (2009). Older adolescents’ motivations for social network site use: The influence of gender, group identity, and collective self-esteem. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(2), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0228

Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (2000). The odds ratio. British Medical Journal, 320(7247), 1468–1468. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1468

*Bonsaksen, T., Schoultz, M., Thygesen, H., Ruffolo, M., Price, D., Leung, J., & Geirdal, A. Ø. (2021). Loneliness and its associated factors nine months after the covid-19 outbreak: A cross-national study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 1–1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062841

*Boursier, V., Gioia, F., Musetti, A., & Schimmenti, A. (2020). Facing loneliness and anxiety during the COVID-19 isolation: The role of excessive social media use in a sample of Italian adults. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 586222–586222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586222

Brunborg, G. S., & Andreas, J. B. (2019). Increase in time spent on social media is associated with modest increase in depression, conduct problems, and episodic heavy drinking. Journal of Adolescence, 74, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.06.013

Bucci, S., Schwannauer, M., & Berry, N. (2019). The digital revolution and its impact on mental health care. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 92(2), 277–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12222

Cauberghe, V., Van Wesenbeeck, I., De Jans, S., Hudders, L., & Ponnet, K. (2021). How adolescents use social media to cope with feelings of loneliness and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdown. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(4), 250–257. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0478

*Chakraborty, T., Kumar, A., Upadhyay, P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2021). Link between social distancing, cognitive dissonance, and social networking site usage intensity: A country-level study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Internet Research, 31(2), 419–456. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-05-2020-0281

Chan, M. (2015). Mobile phones and the good life: Examining the relationships among mobile use, social capital and subjective well-being. New Media & Society, 17(1), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813516836

Chao, M., Xue, D., Liu, T., Yang, H., & Hall, B. J. (2020). Media use and acute psychological outcomes during COVID-19 outbreak in China. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74, 102248–102248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102248

Chen, W., & Lee, K. H. (2013). Sharing, liking, commenting, and distressed? The pathway between Facebook interaction and psychological distress. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(10), 728–734. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0272

Chen, H.-T., & Li, X. (2017). The contribution of mobile social media to social capital and psychological well-being: Examining the role of communicative use, friending and self-disclosure. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 958–965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.011

*Chen, I. H., Chen, C. Y., Pakpour, A. H., Griffiths, M. D., & Lin, C. Y. (2020). Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 school suspension. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(10), 1099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.06.007

*Chen, C. Y., Chen, I. H., O’Brien, K. S., Latner, J. D., & Lin, C. Y. (2021a). Psychological distress and internet-related behaviors between schoolchildren with and without overweight during the COVID-19 outbreak. International Journal of Obesity, 45(3), 677–686.

*Chen, I.-H., Chen, C.-Y., Pakpour, A. H., Griffiths, M. D., Lin, C.-Y., Li, X.-D., & Tsang, H. W. H. (2021b). Problematic internet-related behaviors mediate the associations between levels of internet engagement and distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 lockdown: A longitudinal structural equation modeling study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(1), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00006

*Chen, Y., Wu, J., Ma, J., Zhu, H., Li, W., & Gan, Y. (2021c). The mediating effect of media usage on the relationship between anxiety/fear and physician–patient trust during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology & Health, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2021.1900573

Christensen, S. P. (2018). Social media use and its impact on relationships and emotions [Master Thesis, Brigham Young University]. BYUScholarsArchive. http://hdl.lib.byu.edu/1877/etd10188

Chu, P. S., Saucier, D. A., & Hafner, E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(6), 624–645. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2010.29.6.624

*Clavier, T., Popoff, B., Selim, J., Beuzelin, M., Roussel, M., Compere, V., Veber, B., & Besnier, E. (2020). Association of social network use with increased anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic in anesthesiology, intensive care, and emergency medicine teams: Cross-sectional web-based survey study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(9), e23153–e23153. https://doi.org/10.2196/23153

Cuadros, O., & Berger, C. (2016). The protective role of friendship quality on the wellbeing of adolescents victimized by peers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(9), 1877–1888. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0504-4

*Cuara, J. M. (2020). Social Media Use and the Relationship between Mental, Social, and Physical Health in College Students [Doctoral dissertation, California Baptist University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. https://www.proquest.com/openview/33a4d12aa4c7ac04c047a64baacb92e6/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Cunningham, S., Hudson, C. C., & Harkness, K. (2021). Social media and depression symptoms: A meta-analysis. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(2), 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00715-7

David, J. L., Powless, M. D., Hyman, J. E., Purnell, D. M., Steinfeldt, J. A., & Fisher, S. (2018). College student athletes and social media: The psychological impacts of Twitter use. International Journal of Sport Communication, 11(2), 163–186. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2018-0044

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Dougall, A. L., Hyman, K. B., Hayward, M. C., McFeeley, S., & Baum, A. (2001). Optimism and traumatic stress: The importance of social support and coping. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(2), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00195.x

*Drouin, M., McDaniel, B. T., Pater, J., & Toscos, T. (2020). How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 23(11), 727–736. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0284

Dunbar, R. I. (2016). Do online social media cut through the constraints that limit the size of offline social networks? Royal Society Open Science, 3(1), 150292. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150292

Ebrahim, A. H., Saif, Z. Q., Buheji, M., AlBasri, N., Al-Husaini, F. A., & Jahrami, H. (2020). COVID-19 information-seeking behavior and anxiety symptoms among parents. OSP Journal of Health Care and Medicine, 1(1), 1–9.

*Eden, A. L., Johnson, B. K., Reinecke, L., & Grady, S. M. (2020). Media for coping during COVID-19 social distancing: Stress, anxiety, and psychological well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3388. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577639

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

*Ellis, W. E., Dumas, T. M., & Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 52(3), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000215

Ellison, N., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Exploring the relationship between college students. Use of Online Social Networks and Social Capital’. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Engle, S., Stromme, J., & Zhou, A. (2020). Staying at home: mobility effects of Covid-19. Available at SSRN 3565703.

Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., & Davila, J. (2013). Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a mechanism. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(3), 161. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033111

*Fernandes, B., Biswas, U. N., Tan-Mansukhani, R., Vallejo, A., & Essau, C. A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on internet use and escapism in adolescents. Revista de Psicología Clínica Con Niños y Adolescentes, 7(3), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2020.mon.2056

Fox, J., & Vendemia, M. A. (2016). Selective self-presentation and social comparison through photographs on social networking sites. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(10), 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0248

*Fumagalli, E., Dolmatzian, M. B., & Shrum, L. (2021). Centennials, FOMO, and loneliness: An investigation of the impact of social networking and messaging/VoIP apps usage during the initial stage of the coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 620739–620739. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.620739

GlobalWebIndex (2015). Use of social media by Generation Insights Infographic. GWI. https://www.gwi.com/reports/social-media-across-generations

Groarke, J. M., Berry, E., Graham-Wisener, L., McKenna-Plumley, P. E., McGlinchey, E., & Armour, C. (2020). Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 psychological wellbeing study. PLoS ONE, 15(9), e0239698–e0239698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239698

Güngör, A., Karaman, M. A., Sarı, H. İ, & Çolak, T. S. (2020). Investigating the factors related to Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on undergraduate students’ interests in coursework. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 7(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.17220/ijpes.2020.03.001

*Hammad, M. A., & Alqarni, T. M. (2021). Psychosocial effects of social media on the Saudi society during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0248811–e0248811. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248811

Harkness, K., Cunningham, S., & Hudson, C. C. (2021). Social media and depression symptoms: a meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 49(2), 241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00715-7

Hartanto, A., Yong, J. C., Toh, W. X., Tng, G. Y. Q., & Tov, W. (2020). Cognitive, social, emotional, and subjective health benefits of computer use in adults: A 9-year longitudinal study from the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS). Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106179

Hartanto, A., Lua, V. Y., Quek, F. Y., Yong, J. C., & Ng, M. H. (2021a). A critical review on the moderating role of contextual factors in the associations between video gaming and well-being. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4, 100135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100135

Hartanto, A., Quek, F. Y., Tng, G. Y., & Yong, J. C. (2021b). Does social media use increase depressive symptoms? A reverse causation perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 641934. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.641934

Hayran, C., & Anik, L. (2021). Well-being and fear of missing out (FOMO) on digital content in the time of covid-19: A correlational analysis among university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041974

*Hikmah, K., Prisandy, L., Melinda, G., & Ayatullah, M. I. (2020). An online survey: Assessing anxiety level among general population during the Coronavirus disease-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 8(T1), 451–458. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2020.5386

Houben, M., Van Den Noortgate, W., & Kuppens, P. (2015). The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 901. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038822

Huang, C. (2017). Time spent on social network sites and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(6), 346–354.

Hunt, M. G., Marx, R., Lipson, C., & Young, J. (2018). No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37(10), 751–768. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751

Hunter, P. (2020). The growth of social media in science: Social media has evolved from a mere communication channel to an integral tool for discussion and research collaboration. EMBO Reports, 21(5), e50550–e50550. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202050550

*Ikizer, G., Karanci, A. N., Gul, E., & Dilekler, I. (2021). Post-traumatic stress, growth, and depreciation during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Turkey. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1872966–1872966. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1872966

Ivie, E. J., Pettitt, A., Moses, L. J., & Allen, N. B. (2020). A meta-analysis of the association between adolescent social media use and depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.014

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

Kemp, S. (2021). Half a billion users joined social in the last year (and Other Facts). Social Media Marketing & Management Dashboard. https://blog.hootsuite.com/simon-kemp-social-media/

Killgore, W. D., Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C., Miller, M. A., & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Three months of loneliness during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113392–113392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113392

Kim, A. J., & Johnson, K. K. (2016). Power of consumers using social media: Examining the influences of brand-related user-generated content on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.047

Kırcaburun, K., Kokkinos, C. M., Demetrovics, Z., Király, O., Griffiths, M. D., & Çolak, T. S. (2019). Problematic online behaviors among adolescents and emerging adults: Associations between cyberbullying perpetration, problematic social media use, and psychosocial factors. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(4), 891–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9894-8

*Krause, A. E., Dimmock, J., Rebar, A. L., & Jackson, B. (2021). Music listening predicted improved life satisfaction in university students during early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 631033–631033. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.631033

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukopadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53(9), 1017–1031. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.53.9.1017

*Krendl, A. C., & Perry, B. L. (2021). The impact of sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults’ social and mental well-being. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(2), e53–e58. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa110

*Lake, C. (2020). Social isolation, fear of missing out, and social media use in deaf and hearing college students [Master Thesis, Rochester Institute of Technology]. RIT Scholar Works. https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses/10671

Lardo, A., Dumay, J., Trequattrini, R., & Russo, G. (2017). Social media networks as drivers for intellectual capital disclosure: Evidence from professional football clubs. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-09-2016-0093

Lee, S. J. (2009). Online communication and adolescent social ties: Who benefits more from Internet use? Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(3), 509–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01451.x

Lee, P. S. N., Leung, L., Lo, V., Xiong, C., & Wu, T. (2011). Internet communication versus face-to-face interaction in quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 100(3), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9618-3

*Lemenager, T., Neissner, M., Koopmann, A., Reinhard, I., Georgiadou, E., Müller, A., Kiefer, F., & Hillemacher, T. (2021). Covid-19 lockdown restrictions and online media consumption in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010014

Lin, L. Y., Sidani, J. E., Shensa, A., Radovic, A., Miller, E., Colditz, J. B., Hoffman, B. L., Giles, L. M., & Primack, B. A. (2016). Association between social media use and depression among US young adults. Depression and Anxiety, 33(4), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22466

Lin, C.-Y., Broström, A., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2020). Investigating mediated effects of fear of COVID-19 and COVID-19 misunderstanding in the association between problematic social media use, psychological distress, and insomnia. Internet Interventions : The Application of Information Technology in Mental and Behavioural Health, 21, 100345–100345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2020.100345

*Lisitsa, E., Benjamin, K. S., Chun, S. K., Skalisky, J., Hammond, L. E., & Mezulis, A. H. (2020). Loneliness among young adults during Covid-19 pandemic: The mediational roles of social media use and social support seeking. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 39(8), 708–726. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2020.39.8.708

Liu, D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2016). Social networking online and personality of self-worth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 64, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.06.024

Liu, D., Baumeister, R. F., Yang, C., & Hu, B. (2019). Digital communication media use and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 24(5), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmz013

Liu, H., Liu, W., Yoganathan, V., & Osburg, V.-S. (2021). COVID-19 information overload and generation Z’s social media discontinuance intention during the pandemic lockdown. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 166, 120600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120600

*Magson, N. R., Freeman, J. Y. A., Rapee, R. M., Richardson, C. E., Oar, E. L., & Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9

Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., & Spada, M. M. (2018). The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 226, 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.007

Marttila, E., Koivula, A., & Räsänen, P. (2021). Does excessive social media use decrease subjective well-being? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between problematic use, loneliness and life satisfaction. Telematics and Informatics, 59, 101556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101556

Mascheroni, G., Vincent, J., & Jimenez, E. (2015). “Girls are addicted to likes so they post semi-naked selfies”: Peer mediation, normativity and the construction of identity online. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2015-1-5

*Masciantonio, A., Bourguignon, D., Bouchat, P., Balty, M., & Rimé, B. (2021). Don’t put all social network sites in one basket: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, and their relations with well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0248384–e0248384. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248384

McCain, J. L., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Narcissism and social media use: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 7(3), 308. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000137

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Brashears, M. E. (2006). Social isolation in America: Changes in core discussion networks over two decades. American Sociological Review, 71(3), 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100301

Mendeley. (n.d.) . Mendeley Desktop v1.19.4 [Software]. Mendeley. https://www.mendeley.com/autoupdates/installers/1.19.4

Milani, L., Osualdella, D., & Di Blasio, P. (2009). Quality of interpersonal relationships and problematic Internet use in adolescence. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12(6), 681–684. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2009.0071

Misra, R., Crist, M., & Burant, C. J. (2003). Relationships among life stress, social support, academic stressors, and reactions to stressors of international students in the United States. International Journal of Stress Management, 10(2), 137–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.10.2.137

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., the PRISMA Group. (2009). Reprint—Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Physical Therapy, 89(9), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/89.9.873

Nakagomi, A., Shiba, K., Kondo, K., & Kawachi, I. (2020). Can online communication prevent depression among older people? A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(1), 733464820982147–733464820982147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820982147

Naslund, J. A., Aschbrenner, K. A., Marsch, L. A., & Bartels, S. J. (2016). The future of mental health care: peer-to-peer support and social media. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796015001067

Nesi, J., Choukas-Bradley, S., & Prinstein, M. J. (2018). Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: Part 1—A theoretical framework and application to dyadic peer relationships. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(3), 267–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0261-x

Neto, R., Golz, N., & Polega, M. (2015). Social media use, loneliness, and academic achievement: A correlational study with urban high school students. Journal of Research in Education, 25(2), 28–37.

Newson, M., Zhao, Y., El Zein, M., Sulik, J., Dezecache, G., Deroy, O., & Tuncgenc, B. (2021). Digital contact does not promote wellbeing, but face-to-face does: A cross-national survey during the Covid-19 pandemic. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211062164

Nieminen, T., Martelin, T., Koskinen, S., Aro, H., Alanen, E., & Hyyppä, M. T. (2010). Social capital as a determinant of self-rated health and psychological well-being. International Journal of Public Health, 55(6), 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-010-0138-3

O’Keeffe, G. S., & Clarke-Pearson, K. (2011). The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics, 127(4), 800–804. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0054

Oksanen, A., Oksa, R., Savela, N., Mantere, E., Savolainen, I., & Kaakinen, M. (2021). COVID-19 crisis and digital stressors at work: A longitudinal study on the Finnish working population. Computers in Human Behavior, 122, 106853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106853

Oxford, L., Dubras, R., Currey, H., & Nazir, M. (2020). Digital 2020: 3.8 billion people use social media. We Are Social. https://wearesocial.com/blog/2020/01/digital-2020-3-8-billion-people-use-social-media

Park, N., Song, H., & Lee, K. M. (2014). Social networking sites and other media use, acculturation stress, and psychological well-being among East Asian college students in the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.037

Pastor, D. A., & Lazowski, R. A. (2018). On the multilevel nature of meta-analysis: A tutorial, comparison of software programs, and discussion of analytic choices. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 53(1), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2017.1365684

*Patabendige, M., Gamage, M. M., Weerasinghe, M., & Jayawardane, A. (n.d.). Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among pregnant women in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics, 15(1), 150–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13335

Pavlíček, A. (2013). Social media–the good, the bad, the ugly. IDIMT-2013, 139.

Perloff, R. M. (2014). Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles, 71(11), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6

Pew Research Center. (2021). Demographics of social media users and adoption in the United States. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 250. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250

Reich, S. M., Subrahmanyam, K., & Espinoza, G. (2012). Friending, IMing, and hanging out face-to-face: Overlap in adolescents’ online and offline social networks. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 356. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026980

*Reiss, S., Franchina, V., Jutzi, C., Willardt, R., & Jonas, E. (2020). From anxiety to action—Experience of threat, emotional states, reactance, and action preferences in the early days of COVID-19 self-isolation in Germany and Austria. PLoS ONE, 15(12), e0243193–e0243193. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243193

*Rens, E., Smith, P., Nicaise, P., Lorant, V., & Van den Broeck, K. (2021). Mental distress and its contributing factors among young people during the first wave of COVID-19: A Belgian survey study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 575553–575553. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.575553

Revelle, W. (2022). psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. R package version 2.2.3, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

*Riehm, K. E., Holingue, C., Kalb, L. G., Bennett, D., Kapteyn, A., Jiang, Q., Veldhuis, C. B., Johnson, R. M., Fallin, M. D., Kreuter, F., Stuart, E. A., & Thrul, J. (2020). Associations between media exposure and mental distress among US adults at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(5), 630–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.008

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Saiphoo, A. N., & Vahedi, Z. (2019). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.028

Sandvik, E., Diener, E., & Seidlitz, L. (2009). Subjective well-being: The convergence and stability of self-report and non-self-report measures. In Assessing well-being (pp. 119–138). Springer, Dordrecht.

*Şentürk, E., Geniş, B., Menkü, B. E., Cosar, B., & Karayagmurlu, A. (2021). The effects of social media news that users trusted and verified on anxiety level and disease control perception in COVID-19 pandemic. Klinik Psikiyatri Dergisi, 24(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.5505/kpd.2020.69772

*Sewall, C. J., Goldstein, T. R., & Rosen, D. (2021). Objectively measured digital technology use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Impact on depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among young adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 288, 145–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.008

Song, H., Zmyslinski-Seelig, A., Kim, J., Drent, A., Victor, A., Omori, K., & Allen, M. (2014). Does Facebook make you lonely?: A meta analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 446–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.011

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Stanton, R., To, Q. G., Khalesi, S., Williams, S. L., Alley, S. J., Thwaite, T. L., Fenning, A. S., & Vandelanotte, C. (2020). Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: Associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114065

Statista Research Department. (2020). Number of social network users worldwide from 2017 to 2025 (in billions) [Graph]. Statista. https://www-statista-com.libproxy.smu.edu.sg/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/

Statista Research Department. (2021a). U.S. TikTok user growth 2024 [Graph]. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1100842/tiktok-us-user-growth/

Statista Research Department. (2021b). Topic: Social media use During coronavirus (COVID-19) worldwide. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/7863/social-media-use-during-coronavirus-covid-19-worldwide/

Stern, S. (2008). Producing sites, exploring identities: Youth online authorship (pp. 95–118). MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Initiative.

Sterne, J. A., & Egger, M. (2001). Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(10), 1046–1055.

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. Norton.

*Sun, R., Rieble, C., Liu, Y., & Sauter, D. (2020). Connected despite COVID-19: The role of social interactions and social media for wellbeing [Preprint]. PsyArXiy. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/x5k8u

Tanaka-Matsumi, J., & Kameoka, V. A. (1986). Reliabilities and concurrent validities of popular self-report measures of depression, anxiety, and social desirability. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(3), 328.

*Teresa, M. T., Guss, C. D., & Boyd, L. (2021). Thriving during COVID-19: Predictors of psychological well-being and ways of coping. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0248591–e0248591. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248591

Vahedi, Z., & Zannella, L. (2021). The association between self-reported depressive symptoms and the use of social networking sites (SNS): A meta-analysis. Current Psychology, 40(5), 2174–2189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-0150-6

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2007). Online communication and adolescent well-being: Testing the stimulation versus the displacement hypothesis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1169–1182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00368.x

Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Roberts, L. R., & Eckles, K. (2014). Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3(4), 206. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000047

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Okdie, B. M., Eckles, K., & Franz, B. (2015). Who compares and despairs? The effect of social comparison orientation on social media use and its outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.026

Wang, W., Qian, G., Wang, X., Lei, L., Hu, Q., Chen, J., & Jiang, S. (2019). Mobile social media use and self-identity among Chinese adolescents: the mediating effect of friendship quality and the moderating role of gender. Curr Psychol, 40, 4479-4487 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00397-5

Weinstein, E. (2018). The social media see-saw: Positive and negative influences on adolescents’ affective well-being. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3597–3623. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818755634

*Wheaton, M. G., Prikhidko, A., & Messner, G. R. (2021). Is fear of COVID-19 contagious? The effects of emotion contagion and social media use on anxiety in response to the Coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 567379–567379. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567379

Whittaker, E., & Kowalski, R. M. (2015). Cyberbullying via social media. Journal of School Violence, 14(1), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.949377

Worsley, J. D., McIntyre, J. C., Bentall, R. P., & Corcoran, R. (2018). Childhood maltreatment and problematic social media use: The role of attachment and depression. Psychiatry Research, 267, 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.023

Wrzus, C., Wagner, J., Hänel, M., & Neyer, F. J. (2013). Social network changes and life events across the life span: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 53–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028601

Yang, C., Brown, B. B., & Braun, M. T. (2014). From Facebook to cell calls: Layers of electronic intimacy in college students’ interpersonal relationships. New Media & Society, 16(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812472486

Yang, F. R., Wei, C. F., & Tang, J. H. (2019). Effect of Facebook social comparison on well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Internet Technology, 20(6), 1829–1836. https://doi.org/10.3966/160792642019102006013

*Yang, X., Yip, B. H., Mak, A. D., Zhang, D., Lee, E. K., & Wong, S. Y. (2021). The differential effects of social media on depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among the younger and older adult population in Hong Kong during the COVID-19 pandemic: Population-based cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 7(5), e24623. https://doi.org/10.2196/24623

*Zhao, N., & Zhou, G. (2021). COVID-19 stress and addictive social media use (SMU): Mediating role of active use and social media flow. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 635546–635546. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.635546

Zywica, J., & Danowski, J. (2008). The faces of Facebookers: Investigating social enhancement and social compensation hypotheses; predicting Facebook™ and offline popularity from sociability and self-esteem, and mapping the meanings of popularity with semantic networks. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.01429.x

Funding

This research was supported by grants awarded to Andree Hartanto by Singapore Management University through research grants from the Ministry of Education Academy Research Fund Tier 1 (21-SOSS-SMU-023) and Lee Kong Chian Fund for Research Excellence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

No new data was produced in this work.

Conflict of Interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, J., Yi, P.X., Quek, F.Y.X. et al. A four-level meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media and well-being: a fresh perspective in the context of COVID-19. Curr Psychol 43, 14972–14986 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04092-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04092-w