The History of Russian Involvement in America's Race Wars

From propaganda posters to Facebook ads, 80-plus years of Russian meddling.

According to a spate of recent reports, accounts tied to the St. Petersburg-based Internet Research Agency—a Russian “troll factory”— used social media and Google during the 2016 electoral campaign to deepen political and racial tensions in the United States. The trolls, according to an interview with the Russian TV network TV Rain, were directed to focus their tweets and comments on socially divisive issues, like guns. But another consistent theme has been Russian trolls focusing on issues of race. Some of the Russian ads placed on Facebook apparently targeted Ferguson and Baltimore, which were rocked by protests after police killings of unarmed black men; another showed a black woman firing a rifle. Other ads played on fears of illegal immigrants and Muslims, and groups like Black Lives Matter.

Except for the technology used, however, these tactics are not exactly new. They are natural outgrowths of a central component of covert influence campaigns, like the one Russia launched against the United States during the 2016 election: make discord louder; divide and conquer. “Covert influence campaigns don’t create divisions on the ground, they amplify divisions on the ground,” says Michael Hayden, who ran the NSA under Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush and then became CIA director. During the Cold War, the Kremlin similarly sought to plant fake news and foment discontent, but was limited by the low-tech methods available at the time. “Before, the Soviets would plant information in Indian papers and hope it would get picked up by our papers,” says John Sipher, who ran the CIA’s Russia desk during George W. Bush’s first term. The Soviets planted misinformation about the AIDS epidemic as a Pentagon creation, according to Sipher, as well as the very concept of a nuclear winter. “Now, because of the technology, you can jump right in,” Sipher says.

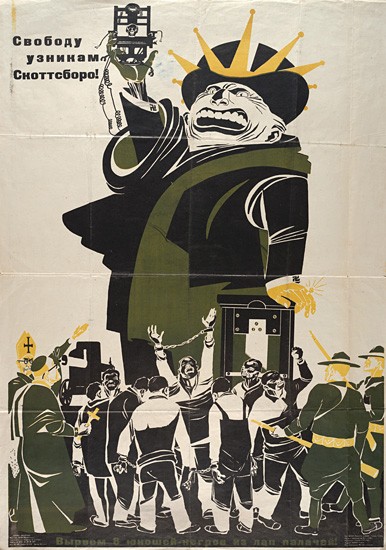

Neither is playing on racial tensions inside the United States a new Russian tactic. In fact, it predates even the Cold War. In 1932, for instance, Dmitri Moor, the Soviet Union’s most famous propaganda poster artist, created a poster that cried, “Freedom to the prisoners of Scottsboro!” It was a reference to the Scottsboro Boys, nine black teenagers who were falsely accused of raping two white women in Alabama, and then repeatedly—wrongly—convicted by all-white Southern juries. The case became a symbol of the injustices of the Jim Crow South, and the young Soviet state milked it for all the propagandistic value it could.

It was part of a plan put in place in 1928 by the Comintern—the Communist International, whose mission was to spread the communist revolution around the world. The plan initially called for recruiting Southern blacks and pushing for “self-determination in the Black Belt.” By 1930, the Comintern had escalated the aims of its covert mission, and decided to work toward establishing a separate black state in the South, which would provide it with a beachhead for spreading the revolution to North America.

The Soviets also exploited the oppression of Southern blacks for their own economic benefit. It was the height of the Great Depression, and the Soviet Union was positioning itself not only as a workers’ utopia, but as a racial utopia as well, one where ethnic, national, and religious divisions didn’t exist. In addition to luring thousands of white American workers, it brought over African-American workers and sharecroppers with the promise of the freedom to work and live unburdened by the violent restrictions of Jim Crow. In return, they would help the Soviets build their fledgling cotton industry in Central Asia. Several hundred answered the call, and though many eventually went back—or died in the Gulag—some of their descendants remain in Russia. One of Russia’s best-known television hosts, for instance, is Yelena Khanga, the granddaughter of Oliver Golden, an agronomist from Tuskeegee University who moved with his communist Jewish-American wife to Uzbekistan to develop the cotton industry there.

The beginning of the Cold War coincided with the beginning of the civil rights movement, and the two became intertwined—both in how the Soviets used the racial strife, and how the Cold War propelled the cause of civil rights forward. “Early on in the Cold War, there was a recognition that the U.S. couldn’t lead the world if it was seen as repressing people of color,” says Mary Dudziak, a legal historian at Emory, whose book Cold War Civil Rights is the seminal work on the topic. When, in September 1957, the Arkansas governor Orval Faubus deployed the National Guard to keep nine black students from integrating the Central High School in Little Rock, the standoff was covered by newspapers around the world, many of which noted the discrepancy between the values America expressed and hoped to spread around the world, and how it implemented them at home.

The Soviets, again, took full advantage of the opportunity. Komsomolskaya Pravda, the newspaper of the communist youth organization in the USSR, ran a sensational story, complete with photographs, about the conflict under the headline, “Troops Advance Against Children!” Izvestia, the second main Soviet daily, also extensively covered the Little Rock crisis, noting at one point that “right now, behind the facade of the so-called ‘American democracy,’ a tragedy is unfolding which cannot but arouse ire and indignation in the heart of every honest man.” The story went on:

The patrons of Governor Faubus ... who dream of nooses and dynamite for persons with different-colored skins, advocates of hooliganism who throw rocks at defenseless Negro children—these gentlemen have the audacity to talk about “democracy” and speak as supporters of “freedom.” In fact it is impossible to imagine a greater insult to democracy and freedom than an American diplomat's speech from the tribunal of the U.S. General Assembly, a speech in which Washington was pictured as the “champion” of the rights of the Hungarian people.

The point then, as it was in 2016, was to discredit the American system, to keep the Soviets (and, later, Russians) loyal to their own system instead of hungering for Western-style democracy. But it was also used in Soviet propaganda around the world for a similar purpose. “This is a principal Soviet propaganda theme,” says Dudziak of the Soviet messaging at the time. “What’s described as communist propaganda that circulated in India overplays the story sometimes but also very maudlin stories about things that actually happened. Sometimes, in Pravda, all they needed to do was to reprint something that appeared in Time Magazine. Just the facts would themselves inflame international opinion. On top of that, the Soviets would push the envelope.”

This came at a critical time for time for the United States. After World War II, the U.S. was a new global power locked in an ideological struggle with the Soviet Union. As the United States tried to convince countries to join its sphere by taking up democracy and liberal values, the U.S. government was competing with the Soviets in parts of the world where images of white cops turning fire hoses and attack dogs on black protesters did not sit well—especially considering that this was coinciding with the wave African countries declaring independence from white colonial rulers. “Here at the United Nations I can see clearly the harm that the riots in Little Rock are doing to our foreign relations,” Henry Cabot Lodge, then the U.S. ambassador to the UN, wrote to President Eisenhower in 1957. “More than two-thirds of the world is non-white and the reactions of the representatives of these people is easy to see. I suspect that we lost several votes on the Chinese communist item because of Little Rock.”

“The Russian objective then was to disrupt U.S. international relations and undermine U.S. power in the world, and undermine the appeal of U.S. democracy to other countries,” says Dudziak, and Lodge was reflecting a central concern at the State Department at the time: The Soviet propaganda was working. American diplomats were reporting back both their chagrin and the difficulty of preaching democracy when images of the violence around the civil rights movement were reported all over the world, and amplified by Soviet or communist propaganda. On a trip to Latin America, then-Vice President Richard Nixon and his wife were met with protestors chanting, “Little Rock! Little Rock!” Secretary of State John Foster Dulles complained that “this situation was ruining our foreign policy. The effect of this in Asia and Africa will be worse for us than Hungary was for the Russians.” Ultimately, he prevailed on Eisenhower to insert a passage into his national address on Little Rock that directly addressed the discrepancy that Soviet propaganda was highlighting—and spinning as American hypocrisy. Whenever the Soviet Union was criticized for its human rights abuses, the rebuttal became, “And you lynch Negroes.”

Moscow never abandoned these tactics, which became known as “whataboutism,” even after the Soviet Union collapsed. Russian propaganda outlets like Russia Today—now known as RT—have always focused on domestic strife in the United States, be it homelessness or Occupy Wall Street or the Ferguson protests. The Facebook ads focusing on divisive issues like Black Lives Matter are just another page from the old Soviet handbook. The difference this time is that the Russians got better at penetrating the American discussions on these fraught subjects. They became a more effective bellows, amplifying the fire Americans built.

The good news, though, is that America can do things to disarm the propaganda. In the 1950s and 60s, for example, this was one of the reasons that American presidents pushed through various civil rights victories, culminating in the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. This time, Americans can stop blaming the Russians and look at ourselves for what we do to fan the flames—to a far greater extent than the Russians ever could or do. “If there’s anyone to blame, it’s us,” says Sipher. “If we accept the stoking, it’s our fault.”