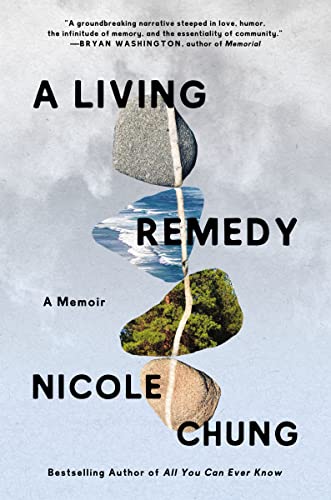

My parents didn’t understand my job. At least, not in its entirety. If asked, they might tell people that their daughter was a writer. They were both avid readers who read my first book and many of my stories; once, when I visited them, I found a newspaper article I’d written stuck to their refrigerator door. On visits, they would occasionally see me working—that is, staring at my computer screen, typing a bit, and staring some more, wrestling with a draft for hours or days. They might be interested in what I was writing, but sometimes it was difficult for them to see it as Work, and they would often mistake it for volunteer labor, a hobby, like the hundreds of stories they knew I’d written growing up. The editorial process, my entire career in publishing, seemed nebulous to them, mostly invisible labor—until I sent them something I’d written that had been published, something they could see and hold and read for themselves.

There were stretches when I made so little money writing or editing that I couldn’t blame my parents for assuming they were hobbies. They used to wonder how I could spend weeks revising work I had already done, months on an idea or project that might never sell. It was hard for me to explain these decisions, explain why I made them even when I could not necessarily afford to. I knew that they wouldn’t have taken such risks. I had grown up watching my parents do what needed to be done, which often meant improvising. My father worked in restaurants for most of my childhood, and my mother did administrative office work. When layoffs came or businesses closed, they found other ways to make ends meet: he stocked shelves at a snack-food company and did yard work for the family for whom my grandmother kept house; she took temp-agency assignments and worked in my middle-school cafeteria. Until a series of medical emergencies hit, they were mostly able to make ends meet.

I don’t know whether witnessing some of these challenges made me more cautious, or more likely to improvise—to grab at passing chances, be open to unlikely opportunities. As someone who grew up in a family that worried about money, I still feel deeply anxious when considering any move that might compromise my stability. At the same time, I’ve learned that it is impossible to pursue one’s creative goals without taking some risks. Though some of the risks I’ve taken have paid off, there are times when I wonder about the associated cost to my family, and whether it was too steep.

I became an editor by volunteering for an Asian American magazine, a nonprofit mission-driven labor of love where no one drew a salary. Ten to fifteen hours of unpaid labor a week in exchange for the editorial experience I wanted was, to me, an acceptable trade—nearly all my labor then was unpaid. I cared for my infant and toddler during the day, then went to writing class at night. I spent every spare moment I had and some that I didn’t pitching freelance pieces and working on my first book proposal.

Then one of my favorite indie websites hired me to edit on a part-time basis. The job started at thirteen dollars an hour, twenty hours a week, and after a couple of months I was brought on full-time and granted a salary in the mid-30s. I loved that role, the tiny team I worked with, our community of readers. I was responsible for editing and publishing two to three freelance pieces a day, reading and responding to hundreds of pitches a week, and handling social media. I found my confidence as an editor, as the volume of work meant I had no time for imposter syndrome. By the time that website shuttered two years later, my salary had risen to the mid-40s. My agent and I had finally managed to sell my first book for a small advance. The independent publisher that acquired it later offered me a job as managing editor of its digital publications, starting at a few thousand more than I’d made in my previous role. Again, I felt lucky, working and collaborating with fellow writers every day—it felt like a dream job.

But there was also a reality I had to face: I was running out of time to help my family. My diabetic father’s health was in decline, and my parents were struggling to pay for his care and medications. My husband and I couldn’t pay for full-time childcare for both our kids, let alone provide the kind of support my parents needed. The little assistance I could offer wasn’t enough to make a dent, and as my father grew sicker, my guilt and anxiety intensified.

At my lowest points, I attacked myself, my choices. What was the point of working and writing all the time, even if I loved it, when I couldn’t help my family in all the ways they needed? I knew that my parents only wanted me to be okay, to be able to sustain and take care of myself. But I had always hoped that I would be able to take care of all of us.

My mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer in the fall of 2019. By then, book royalties, an advance on my next book, and raises at work had given me a kind of security I’d never known before. I could set up an emergency account for my mom, visit her more often, and pay her bills when needed, though all this was cold comfort. But my father was already gone. He had died the year before, leaving both my mother and me to grieve and wonder if we should have been able to do more for him.

I am aware that focusing on individual responsibility can obscure the reality of broken systems. That neither my parents nor I am to blame for what they were up against. That it was always going to be beyond my capacity to provide and pay for all their care out of pocket when they had significant medical needs and, for many years, no healthcare coverage. But I was—I am—their only child, and I not only wanted but expected to be of more help to them. I didn’t know that we would run out of time.

I left my editorial job the year after my mother died. It was not because I was grieving, or at least not only because I was grieving. I had finally realized that I couldn’t write books, take freelance assignments, and work a demanding publishing job without sacrificing too much that was important to me. As a full-time freelancer, I’m currently earning less than I have in years. I don’t kid myself that things would feel less tenuous had I stayed where I was, as the publisher I worked for recently laid off 40% of its workforce and closed the publications I edited.

I continue to grapple with the instability of this industry and what kind of opportunities will be available to me in the years to come, as well as larger questions about whether my editorial work was valued. Whether it was worth it, especially given my family’s needs. I think about who gets to be a writer or an editor, who can afford to wait for that livable salary or that higher advance. Who can choose to prioritize their creative goals, take potentially career-making risks, invest precious years in this work without the guarantee of financial stability. And I think about whose work we may be losing—whose stories we aren’t reading—because they, and perhaps their families, simply cannot afford for them to hang around and wait.

My writing and publishing experience has often felt like an embarrassment of riches, one stroke of luck after another. I can point to what I’ve gained writing books, pursuing bylines, taking on cherished writing and editing roles. But I am also aware of my losses, deep and unrecoverable. It’s hard not to question how much more I might have been able to do for my parents had I pursued work they would have not only understood, but materially benefited from sooner.