Too often, we journalists set aside our critical reasoning skills when it comes to alarming statistics about patient safety.

Take a 2016 analysis published in The BMJ, which suggested that medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the U.S., behind heart disease and cancer.

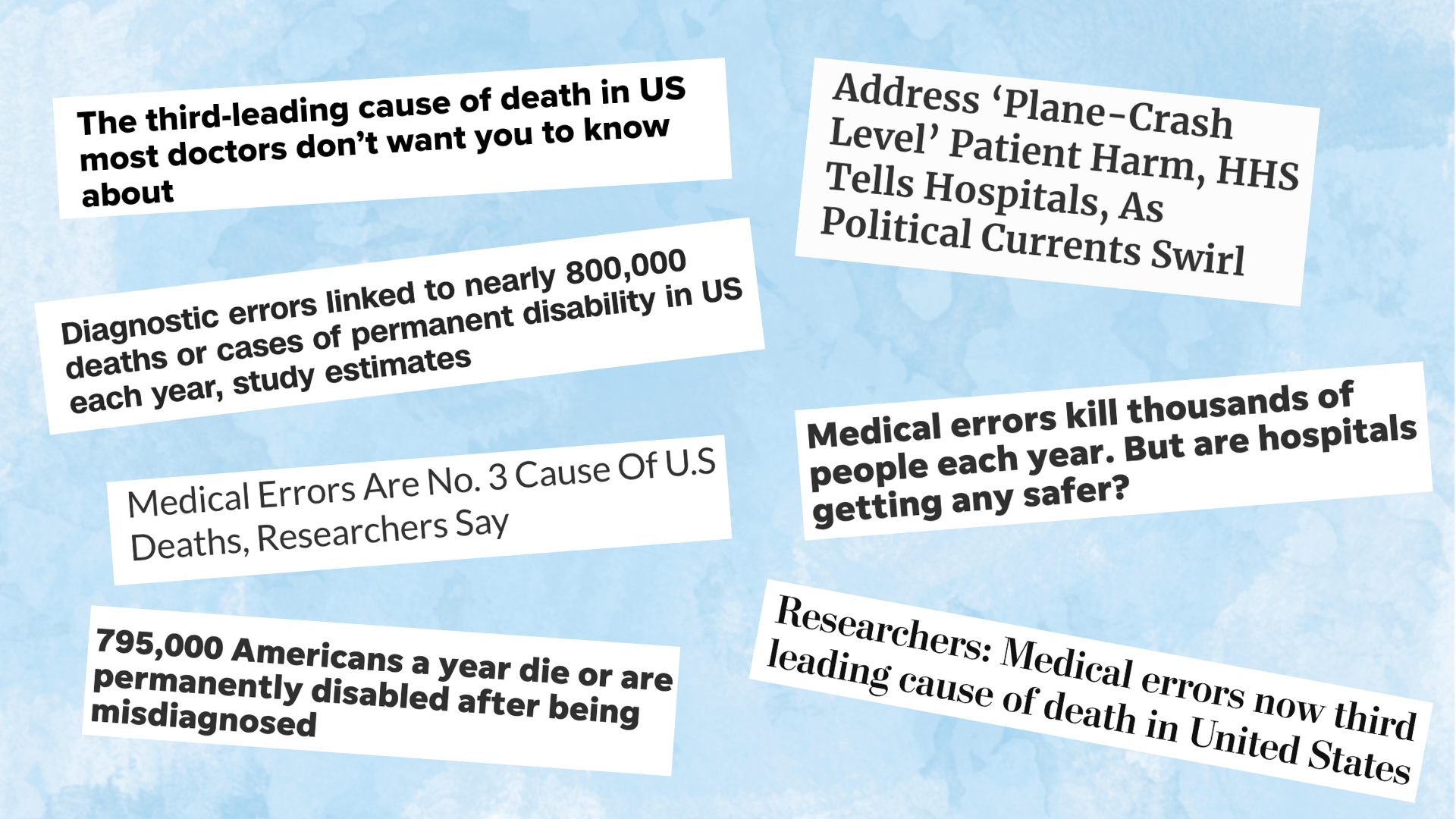

Here are just a few of many credulous headlines:

- STAT: Medical errors are third-leading cause of death in the U.S.

- The Washington Post: Researchers: Medical errors now third leading cause of death in United States.

- NPR: “Medical Errors Are No. 3 Cause Of U.S. Deaths, Researchers Say.”

Missing in the coverage was scrutiny of the researchers’ flawed methods, which involved extrapolating death rates from unrepresentative patient populations and making unsubstantiated causal connections between errors and deaths.

Doing a little basic math might have prompted journalists to ask more questions. The paper said that at least 251,454 people a year die in U.S. hospitals due to mistakes in care. That amounts to a third or more of all people who die in the hospital — an incredible portion.

In a critical commentary, the co-editors-in-chief of the journal BMJ Quality & Safety wrote that the paper’s “headline-friendly” mortality rate — which was 10 times the rate suggested by prior studies — was so implausible that it risked undermining confidence in the entire field of patient safety research.

Yet the notion that medical errors are the third leading cause of death persists. It’s trumpeted by patient safety advocates and trial attorneys, and became a line on a TV show. News stories continue to cite it.

What’s the harm?

Unquestioning coverage also has been given to the 1999 Institute of Medicine’s estimate of 44,000 to 98,000 annual deaths from unsafe care, which prompted the clichéd analogy of a jet crashing every day, and a 2013 paper that claimed annual deaths exceed 400,000.

Meanwhile, lower estimates get ignored. As far as I can tell, no mainstream news outlet covered a 2020 meta-analysis by researchers at Yale University that found evidence of about 22,000 preventable deaths annually, mostly in people with less than three months to live.

Shaky figures keep generating headlines. Last week, USA Today and CNN touted a study saying misdiagnosis kills or permanently disables 795,000 U.S. patients a year. Neither story mentioned the study’s limitations, which included relying on a report that is under re-review for using faulty data.

Journalists aren’t the only culprits. Many researchers are loath to publicly criticize their colleagues’ inflated estimates because sensational headlines draw attention to the problem of medical errors. But critics worry that exaggerating the harms can discourage people from seeking care and offer an excuse for downplaying other serious risks.

Jonathan Jarry, M.S., a science communicator at McGill University, wrote about how the third-leading-cause-of-death narrative has been “weaponized by believers in alternative medicine to paint conventional medicine as dangerous.” Further, the National Rifle Association used inflated medical harm data to argue that medical malpractice is deadlier than gun accidents.

How to do nuanced reporting

Journalists shouldn’t necessarily disregard dubious figures, Jarry told me.

“If a study is making the rounds on social media, covering it is probably a good idea as a way to disentangle reality from hype,” he said.

But nuanced coverage that says medical errors are both a big problem and overstated by a particular study can be difficult, Benjamin Mazer, M.D., a pathologist who wrote about why debatable estimates of medical error are accepted, said in an interview.

Reporters and editors should follow AHCJ’s Statement of Principles, which advises using independent sources to evaluate data and ensuring that headlines don’t mislead.

Here are other suggestions, assembled with input from Jarry and Mazer.

- Include the range of uncertainty. Harms from medical error are difficult to measure, and researchers shouldn’t claim false precision. Report a study’s confidence interval, which indicates if an estimate may be too high or too low.

- Examine who was studied. Small studies in which a handful of patients died can’t reliably predict the entire U.S. death rate. Nor can studies of populations that aren’t representative of all patients nationally, or studies that are decades old.

- Determine how medical errors were defined. Datasets don’t always distinguish between errors that cause death and errors that coincide with death. Also, experts may disagree about whether a death or injury was the result of error.

- Point out studies that show a different result. In addition to those mentioned earlier, reliable reviews in Norway and the United Kingdom put the rate of preventable hospital deaths at 4.2% and 3.6%, respectively, which translates to 25,000 to 30,000 deaths a year in a country the size of the U.S. A recent study of hospital patients in Massachusetts found 1% had preventable adverse events that were serious, life-threatening or fatal. The HHS Office of Inspector General has studied rates of preventable adverse events in Medicare patients.

It’s important to underscore that unsafe care is a major problem, even if serious harms affect a small portion of patients.

“If you’re saying these are truly preventable, that’s awful, and it’s something we should do more about,” Mazer said.