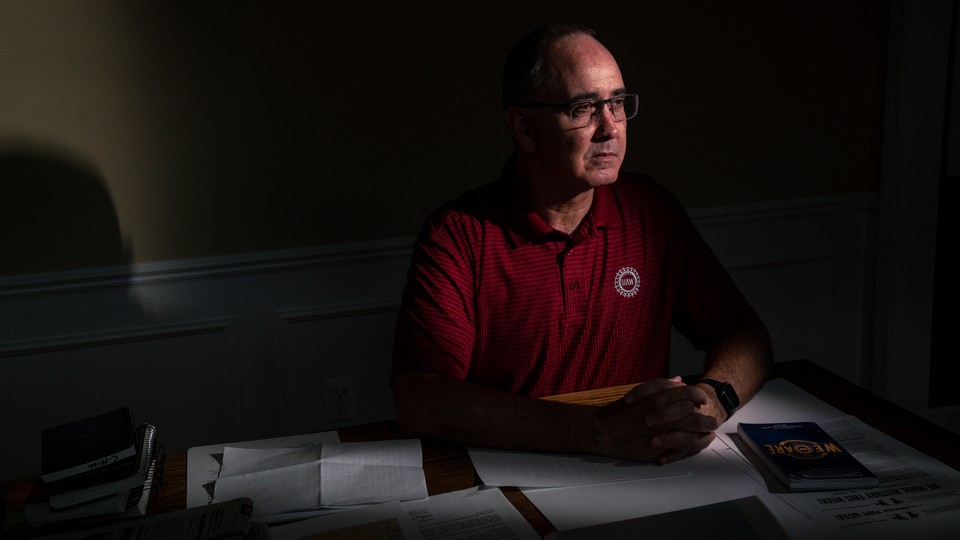

Shawn Fain’s Old-Time Religion

The president of the United Auto Workers is part of a tradition that was once far more visible in American public life: the Christian left.

There’s something sermonic about the speeches of Shawn Fain, the president of the currently striking United Auto Workers. Since autoworkers began targeted work stoppages following the expiration of their contract on September 15, Fain has regularly addressed the public—and his message has a uniquely moral cast.

“I’ve been without,” he told me last month. “I’ve been on unemployment and been on government aid to get formula and diapers for my firstborn child. I mean, that’s when, to me, I leaned on my faith and leaned on God and turned to scripture for answers.”

In a speech delivered in September, Fain, who has been the president of UAW for only a few months, explained that he’d decided to seek the union presidency not only out of practical motives, but also because of his deep faith.

“One of the first things I do every day when I get up is I crack open my devotional for a daily reading, and I pray. Earlier this week, I was struck by the daily reading, which seemed to speak directly to the moment we find ourselves in,” Fain explained in his speech. The commentary Fain read observed that great acts of faith are rarely born of careful calculation, and most often include an element of fear. “When I made the decision to run for president of our union, it was a test of my faith, because I sure as hell had doubts,” Fain said. “So I told myself: Either you believe it’s possible to stand up and make a difference, or you don’t. And if you don’t believe, then shut up and stay on the sideline.”

Fain added that he had chosen to be sworn in to the union’s presidency on his grandmother’s Bible, an heirloom that spoke both to his family’s Christian history and to their working-class roots: “In 1933, at the height of the Depression, my grandmother’s parents couldn’t provide for their children any longer, so they dropped her and her brothers and sisters off at an orphanage. That orphanage gave her this Bible … I’m proud to have inherited my grandma’s Bible and her faith.”

In the early half of the 20th century, the American Christian tradition was rich with justice-oriented, pro-labor theology. Social Christianity, which sought to transform society through fresh policy and organizing, was, at the time, popular across class lines. This strain of Christian faith was distinct from forms that primarily take the directives of the religion to be matters of private morality; it included in its aims social and political renewal. Yet changes in postwar U.S. politics had a marked effect on American religion: By the latter half of the 20th century, more conservative versions of the faith had taken their place in the landscape of Christian belief. Now political conservatism and Christianity appear locked in a feedback loop: As left-leaning people depart an ever more right-leaning Christianity, they inadvertently concentrate their former churches in the hands of conservative members.

This shift can be observed in data on church attendance and party affiliation, according to the researcher Ryan Burge. “Democrats are more likely to be never attenders [of church] than Republicans. That’s the case in every single [birth] cohort and the trend lines run in parallel for most of the cohorts,” Burge wrote in April on his Substack. Among Democrats born from 1990 to 1994, for example, “42% were never attending in 2020. It was only 21% of Republicans. That 2 to 1 gap is really the norm across cohorts.”

Left Christianity may be on track for continued recession in the United States, but Fain is an example of what a vibrant and active pro-labor, pro-justice Christianity might look like today. When I spoke with him last month, he told me that when he was a child, he and his family attended the Missionary Baptist church where his mother’s great-uncle was a pastor. He remembers his grandmother talking to him about faith when he was young: “I don’t want to say I didn’t care, but it wasn’t at that time probably important to me. But it’s funny how, when they plant seeds, that they come back when you’re ready to hear it and when you’re ready to be fed,” Fain said. In his 20s, he added, he began his practice of reading scripture and attending small church groups. He started to turn to his faith for support not just as a Christian, but as a worker.

Fain’s religion seems especially sensitive to the needs of the working poor. Part of the appeal of left Christianity is the notion that all of the resources one needs for sustaining a worldview focused on the needs of workers, the poor, and the dispossessed are already inside the faith. “My favorite verse, period, is Ecclesiastes 4:9–12,” Fain told me. “I mean, that’s to me what the union’s all about; it’s what solidarity’s all about.” Fain recited the verse, which advises that two or more workers striving together achieve greater strength and security than a single worker laboring alone. ”My favorite line in that is ‘A cord of three strands is not easily broken,’” he added. Fain said that the verse “speaks about what life’s about: standing together and helping one another and loving one another.”

Fain told me that his faith was central in his decision to run for president of UAW on the heels of a major corruption crisis in union leadership. “God has a plan. I have a very strong belief in that, faith in that,” he explained. Several incidents had inclined him to run for president, but the turning point, he said, was when he imagined looking at himself in 10 years and contemplating the fact that he had chosen not to stand up for his union. He decided that he wouldn’t be able to live with himself in that case—“and then it really became, again, a question of faith.”

It’s hard not to detect something missing in American Christian culture when speaking with Fain. Churches with a strong preference for liberatory theology still exist—such as some Catholic congregations and Black churches—but they aren’t the dominant tendency in the country’s faith, and they’re not necessarily slated for growth. To me, Fain’s example harkens back to a time when American Christianity was full of possibilities for the poor and downtrodden whom Christ loved so much.