The Blurb Problem Keeps Getting Worse

Publishing has come to depend on fawning endorsements, but not every title can be electrifying, essential, and revelatory.

If there’s one thing authors love more than procrastinating, it’s praising one another. During the Renaissance, Thomas More’s Utopia got a proto-blurb from Erasmus (“divine wit”), while Shakespeare’s First Folio got one from Ben Jonson (“The wonder of our stage!”). By the 18th century, the practice of selling a book based on some other author’s endorsement was so well established that Henry Fielding’s spoof novel Shamela even came with fake blurbs, including one from “John Puff Esq.”

Blurbs have always been controversial—too clichéd, too subject to cronyism—but lately, as review space shrinks and the noise level of the marketplace increases, the pursuit of ever more fawning praise from luminaries has become absurd. Even the most minor title now comes garlanded with quotes hailing it as the most important book since the Bible, while authors report getting so many requests that some are opting out of the practice altogether. Publishers have begun to despair of blurbs, too. “You only need to look at the jackets from the 1990s or 2000s to see that even most debut novelists didn’t have them, or had only one or two genuinely high-quality ones,” Mark Richards, the publisher of the independent Swift Press, told me. “But what happened was an arms race. People figured out that they helped, so more effort was put into getting them, until a point was reached where they didn’t necessarily make any positive difference; it’s just that not having them would likely ruin a book’s chances.”

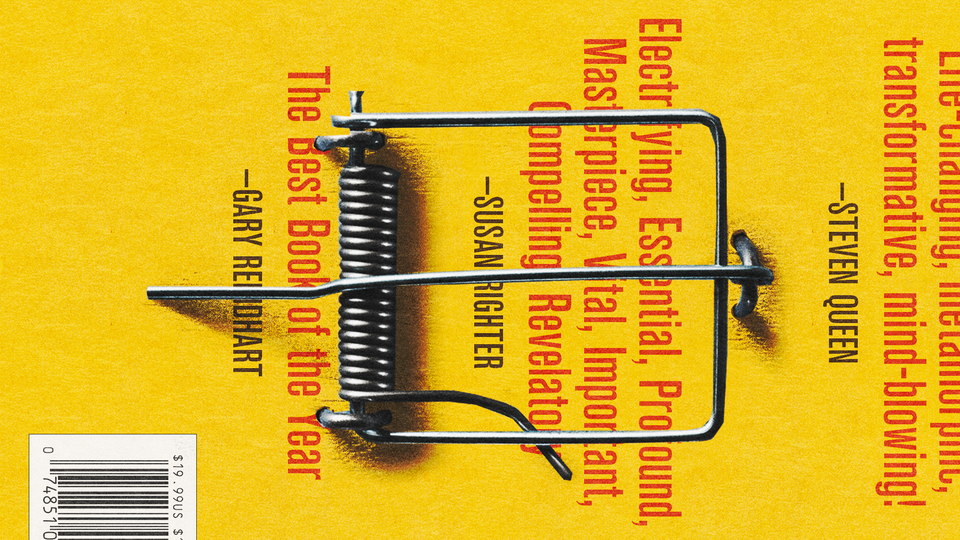

Today, pick up any title at Barnes & Noble and you’re likely to find that it’s plastered with approving adjectives from everyone under the sun. When I asked Henry Oliver, who runs The Common Reader, a Substack devoted to literature, for examples of overused words, he sent back a long list: electrifying, essential, profound, masterpiece, vital, important, compelling, revelatory, myth-busting, masterful, elegantly written, brave, lucid and engaging, indispensable, enlightening, courageous, powerful. “We do it like some kind of sympathetic magic,” John Mitchinson, a co-founder of the book-crowdfunding platform Unbound, told me. “Like a rabbit’s foot … We all do it because we are desperate to prove the book has some merit. There is something slightly troubling about it.”

For first-time authors, offering up contacts for blurbs has become a routine part of the pitching process, along with boasting about how many social-media followers they have. Tomiwa Owolade, whose first book, This Is Not America: Why Black Lives Matter in Britain, came out in June, told me that he, his agent, and his editor drew up a list of potential blurb writers, “and my editor messaged everyone on the list. I don’t know how many on the list responded to the email, or received the book but didn’t read it, or read the book and hated it, and I didn’t pester my editor to find out: I only know of the ones who came back with an endorsement.” One of those who responded was the Dutch author Ian Buruma, a former editor of The New York Review of Books. His unexpected endorsement provided a confidence boost to Owolade, and perhaps a sales boost too. “I’m a big fan of his writing, but we’ve never interacted before,” Owolade said. “I thought it was very sweet of him.”

What’s behind the blurb arms race? Two things: the switch across the arts from a traditional critical culture to an internet-centered one driven by influencers and reliant on user reviews, combined with a superstar system where a handful of titles account for the great majority of sales.

Those trends have disrupted the 20th century’s dominant two-step model of book promotion, in which publishers brought out a hardback—conveying seriousness, prestige, and heft—and then a paperback about a year later. This allowed them two chances to “launch” the book, and the cheaper, more portable paperbacks could also benefit from the (hopefully) glowing reviews for the hardback in major newspapers and magazines.

That model is now broken. Mitchinson and Richards tell the same story: The volume of books being published has become enormous at the same time as many legacy publications have stopped publishing stand-alone book sections; the reviews they do publish have lost much of their cultural impact. So instead of harvesting effusive quotes from professional book reviewers, authors solicit them from celebrities and other writers, usually long before publication. A phalanx of powerful, insightful, vivid blurbs now means the difference between success and failure. In Mitchinson’s 12 years of running Unbound, he says, “it’s moved from sending books out for review, to sending them out at the earliest possible moment for endorsement quotes.” Building excitement before publication day leads to higher preorders, and in turn to more promotion on Amazon and in brick-and-mortar bookstores.

And that reveals another dirty secret of the blurb: They’re not addressed to you. “The biggest thing to understand is that blurbs aren’t principally, or even really at all, aimed at the consumer,” Richards told me via email. “They are instead aimed at literary editors and buyers for the bookstores—in a sea of new books, having blurbs from, ideally, lots of famous writers will make it more likely that they will review/stock your book.”

That’s the magic. Stephen King is well known for his generous praise for less commercially successful authors—which is to say basically all of them—and if he says this is an important book, then it is one. His approval is a signal as powerful as a publisher announcing that it has won a “seven-way” auction or paid a “six-figure sum.” Anointed by greatness, maybe such a golden title will be chosen by Reese Witherspoon’s book club. Maybe it will pick up chatter on TikTok or Instagram. Maybe it will become the title that everyone seems to be talking about, like Yellowface or Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. Blurbs are therefore an uneasy hybrid of quality-assurance mark and publicity gimmick. This makes the practice of blurbing a fraught one. Are you doing a fellow striver a good turn, or acting as a gatekeeper of excellence, making sure that only the best books succeed?

Reading a book takes time, so writers have an incentive to blurb only their friends. Writing a good puff quote takes time too: If you ever see the words inspiring and illuminating, assume the blurber hasn’t even cracked the spine. Most established authors are bombarded with proofs, accompanied by heartstring-tugging notes from editors about the importance of this author’s vision. After writing my own book on feminism, I could have made a fort out of advance copies of other books with women in the title sent to me by hopeful publishers. I can only imagine the number of books Stephen King receives; it must be like a snowdrift on the wrong side of his front door. The distinguished classicist Mary Beard announced a few years ago that she was declining all requests, because she felt like she was becoming a “blurb whore” after being asked at least once a week. “I’m beginning to get a lot more authors who say, I can’t do it,” Mitchinson told me.

Not everyone says that, though. In my reporting for this piece, certain names repeatedly came up as prolific blurbers. “Salman Rushdie, Colm Tóibín, even the reclusive J. M. Coetzee make frequent appearances, so many that you wonder how they find time to read all these books and keep up the day job too,” the critic John Self told me. The British polymath Stephen Fry, meanwhile, “has hilariously blurbed about half of all books published in the U.K.,” said James Marriott of the London Times. His brand is cerebral, patrician, and politically unchallenging. “To me his endorsement means nothing, but I wonder how far casual bookshop visitors get that he puts his name on everything.” (I requested a comment from Fry via his agent but have not yet heard back.)

Unsurprisingly, publishers are grateful to the authors who do participate in the practice. Mark Richards sees them as “good literary citizens.” The novelist Amanda Craig agreed. “My thoughts have done a 180 turn,” she told me. When she published her first book, Foreign Bodies, in 1990, she was offered a cover quote by fellow novelist Deborah Moggach, who was nine years older than her. Craig turned it down because she wanted her work to speak for itself. “I was very purist,” she said. Now, though, the squeeze on reviewing space means that good authors struggle to attract attention, and she has a policy of blurbing “anybody I think is good, including people I thoroughly dislike.”

Craig is also annoyed that the male-dominated golden generation above her, whose members prospered in the 1980s when novels were far more profitable, have largely been reluctant blurbers of their successors. They “got the cream, but it never seemed to have occurred to them … to pass it on,” she told me, adding that she wondered if this had contributed to the decline in male authorship. (The success of men at the very top of publishing—as CEOs of publishing houses, as lead critics on newspapers, and until recently on prize shortlists—obscures the fact that most buyers and readers of books are women, and the industry as a whole is female-dominated.) The generation of women above Craig were supportive because they wanted to see other women succeed, but her male peers today did not benefit from similar solidarity. “When I got Rose Tremain and Penelope Lively, it was like God descending from the clouds,” Craig said. “I do feel for the men of my generation.” The blurb arms race, then, is unfair to many marginalized groups—and men may be one of them.

One obvious thing about blurbs is that they are open to corruption. Ask around and you will quickly discover deep suspicions about, for example, reciprocal blurbing—or what you might call a blurblejerk: “You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours,” as George Orwell once wrote to his friend Cyril Connolly, proposing that they gush about each other’s books in print.

Tactical mutual admiration has always been so common that Spy magazine had a recurring feature called “Log-Rolling In Our Time,” and back in 2001, Slate revealed that Frank McCourt had gone hog wild after the publication of Angela’s Ashes, “doling out 15 blurbs” in five years, including one for the wife of his film producer. (You can see the extent of blurb inflation because, for such a prominent author, three blurbs a year now seems like a low number.)

I learned of Orwell’s logrolling—and the puff quotes by Erasmus and Ben Jonson at the start of this article—from Louise Willder’s fascinating study of book marketing, Blurb Your Enthusiasm. In it, Willder, who writes marketing copy for Penguin Random House, confirms (sadly, without naming names) that some puffers don’t read the books they’re endorsing. “One of the slightly shameful secrets of publishing is that occasionally an author will really want to give an endorsement for a writer they admire, but is too busy to do it—and so they hand the responsibility over to somebody else,” she writes. “I confess that, yes, occasionally I have made up review quotes for a couple of high-profile authors in this manner (although luckily they did find the time to sign off on the finished piece of praise).”

Halfway through our conversation, John Mitchinson revealed the existence of something even more shocking than ghostblurbing. Recently, when he requested a blurb from a public figure via his agent, he said, “they quoted us £1,000.” Wow. I knew the blurbosphere was corrupt, but not that corrupt. Mitchinson declined the offer.

But then, as we talked more, I realized that a celebrity can earn five or six figures for a corporate speech that takes far less time than reading a book and writing a gushing paragraph about it. And in terms of sales, a puff quote from the right person is probably worth far more than a few thousand dollars. Perhaps I was naive to assume, as James Marriott put it, “that publishers—a prestige, highbrow industry—would never indulge in the dark arts of publicity the way, I don’t know, fast-food manufacturers would.”

A blurb has always been a type of currency, and many of the most successful books are not really books at all, but brand extensions for a diet guru or productivity hacker or business titan. Why assume that those authors care about literature? Some probably regard people who read books before blurbing them as hopeless saps who don’t even take ice baths or keep a bullet journal. The fallen crypto billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried once said that he would never read a book, and that anyone who wrote one had screwed up, because “it should have been a six-paragraph blog post.”

Hearing these descriptions of blurbing—which can be both a selfless act and a shamelessly corrupt one—reminded me of nothing so much as academic peer review. Getting a paper published in Science or Nature, or another respected journal, is a coup for any scientist. You have been publicly acknowledged as producing something of value, which has been rigorously checked and endorsed by your community. Your university will appreciate the visibility. Your H-index will be bolstered. You might get more research funding or more time off teaching responsibilities. At the same time, for the big journals, the rewards of publishing more and more papers are also obvious: profits (big ones). But the entire system relies on academics giving up their time for free to assess the submitted work. Devolving this quality-control mechanism onto unpaid peer reviewers has obvious flaws, turning what should be an objective process into one that’s open to political bias, petty score-settling, or plain old laziness. The same is true of relying so much on book blurbs. Publishers make money from books; blurbers don’t (well, mostly). In both science and publishing, the merits of the work are supposed to be paramount, but the structure of the industry means that prestige and connections matter too.

Scientists, being scientists, have methodically built an entire movement—called Open Science—to address these potential problems. Authors, being authors, largely complain about them to their friends. They tell stories of being asked for a blurb and then having their tightly constructed praise discarded in favor of a tossed-off sentence by a more fashionable writer. They whisper that some blurbers are only generous with their praise because it makes them feel important. They confer about who’s a soft touch and whose approval really means something. They claim never to be swayed by blurbs themselves, before revealing that praise from a favorite author did, in fact, prompt them to buy a now-beloved title.

“My own personal view is that there should be a moratorium on them—that we as editors should collectively decide not to put any on any of our books for a year, and reclaim our own taste,” Mark Richards of Swift Publishing told me. “Of course, this won’t happen, so like hamsters we’ll be on the quote treadmill until we finally fall off.”