The Meme That Defined a Decade

Over the past 10 years, the “This Is Fine” dog has evolved from a joke into an indictment.

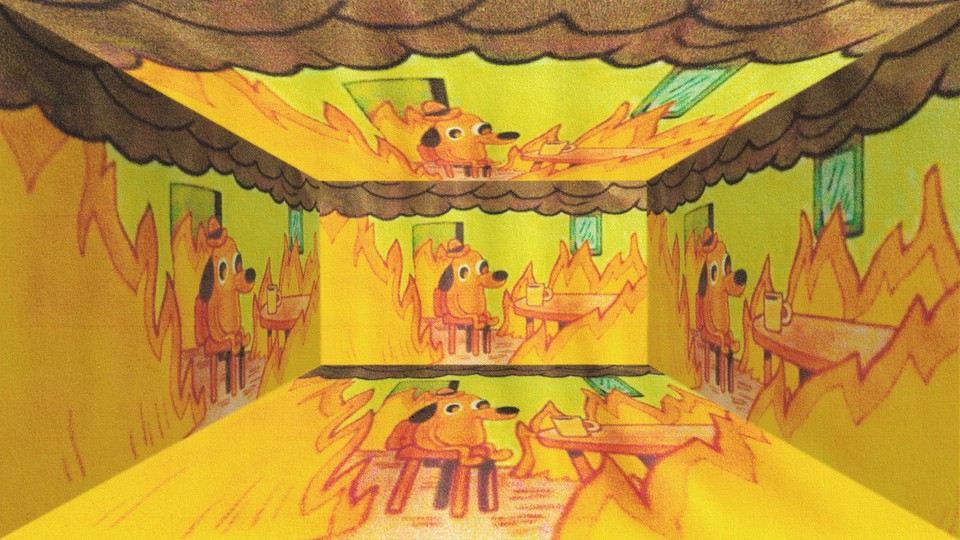

Memes rarely endure. Most explode and recede at nearly the same moment: the same month or week or day. But the meme best known as “This Is Fine”—the one with the dog sipping from a mug as a fire rages around him—has lasted. It is now 10 years old, and it is somehow more relevant than ever. Memes are typically associated with creative adaptability, the image and text editable into nearly endless iterations. “This Is Fine,” though, is a work of near-endless interpretability: It says so much, so economically. That elasticity has contributed to its persistence. The flame-licked dog, that avatar of learned helplessness, speaks not only to individual people—but also, it turns out, to the country.

The meme comes from KC Green’s six-panel comic “On Fire.” In the first, the dog, wearing a small bowler hat, sits at a table, surrounded by flames. In the second, the dog smiles brightly and says, “This is fine.” In the third, as the flames get closer, the still-grinning hound takes a drink of what looks to be coffee and says, “I’m okay with the events that are unfolding currently.” In the fourth, he takes another swig. Here, the panels that have so far maintained a consistent color scheme—yellow, brown, orange—introduce a new color: red. As the dog drinks, his left leg catches fire. “That’s okay, things are going to be okay,” the dog says, his leg now stripped of flesh. The final panel brings the obvious conclusion: Things are not going to be okay. The dog, consumed by the fire, melts away.

Green created “On Fire”—an entry in his comic series Gunshow—in January 2013. For him, the comic represented a kind of reassurance in the face of instability: He had begun taking antidepressants, he’s said in interviews, and was worried about whether the medications would be a good fit for him. (The dog’s full name, appropriately: Question Hound.) Green, in creating “On Fire,” was trying to reassure himself. “It kind of feels like you just have to ignore all the insanity around you like a burning house,” he recently told NPR. “And the comic just ended up writing itself after that.”

When “On Fire” went viral a year later—after users posted the comic’s first two panels to Reddit and the image-sharing site Imgur—many of those who amplified it focused on its potential for self-deprecation: It stood in for the small acts of avoidance and complacency and denial that are familiar features of people’s lives. In the dog surrounded by fire, they saw themselves. Students used the meme to describe feeling unprepared for upcoming tests. Workers used it to describe the stresses of their job. This was the “that feeling when” era of the social web—a moment when people were mining their daily experiences for insights that might be turned into shareable media. And “This Is Fine” applied to many of the situations people found themselves in as they navigated the world. The meme was personal. It was relatable. It could shape-shift for any situation. Its three ironized words—this is fine—were a useful stand-in, The Verge’s Chris Plante put it, “for when a situation becomes so terrible our brains refuse to grapple with its severity.”

Green has compared “This Is Fine” to a “good piece of art,” and the comparison is apt: He made the comic intentionally vague so that it could support very different interpretations. “This Is Fine,” for all its quirky internet-iness, also has a Mona Lisa quality. Question Dog, merrily facing his preventable demise, is effectively smiling and grimacing at once.

By 2016, that flexibility had brought a shift; audiences began to see in the dog not only themselves but their fellow Americans. As many people contended with the fact that Donald Trump might become president—as they watched him announce to the Republican National Convention that “I alone can fix it,” as they reread Orwell, as they wondered what it really might mean to “make America great again”—the dog’s denial broadened to something more national, cultural, collective. Question Hound’s cheerful inertia began to read as a proxy for a shared sense of helplessness: flames everywhere, and nowhere to go.

Once, “the house burning may have just been your final exams,” Green recently told The Washington Post. “Now, it’s feeling like it’s the world, it’s your country.”

Politicians inevitably tried to turn the meme into a message. The GOP’s official Twitter account, reacting to the proceedings of 2016’s Democratic National Convention, invoked “This Is Fine” in an attempt to mock their rivals. Typically, when brands and institutions adopt a meme for their ends, its death will quickly ensue; “This Is Fine,” though, survived. And it has taken on a new sensibility in the process. Question Hound, after years of upheaval and loss—much of it either created or permitted by leaders who, like him, could have put out the fires—doesn’t read merely as a victim. In his willful inaction, he now looks a bit like a villain. He could do something. He chooses not to. He acts out an absurdist version of what so many national politicians have done, essentially, in recent years: He sips his coffee while the world burns. COVID, climate change, fascism, bigotry, mass shootings, book bans, curtailed rights—this is fine, many leaders have said. This is fine, many people have agreed. The flames encroach. Nothing changes.

But memes are ever malleable. And comics can be rewritten. In 2016, Green created an updated version of “On Fire” with an alternative ending. The new comic is titled “This Is Not Fine.” It begins as the classic comic does: Question Hound, seated by the table, surrounded by the flames. “Th—” he begins. And then he wakes from his stupor. “THIS IS NOT FINE!!” he screams, in panic. And then: “Oh my God everything’s on fire,” he says, as his hat falls off and his eyes bug out of his head. He grabs a fire extinguisher. “There was no reason to let it last this long and get this bad,” he says. And then he douses the flames.