Abstract

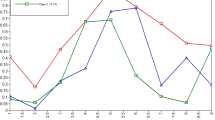

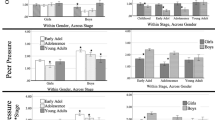

Using a stratified sample of Canadian adolescents residing in Ontario (n = 2,154) time use patterns and perceptions of time pressure are explored to determine gender differences among younger (12–14 years) and older adolescents (15–19 years). For both age groups, girls report a higher total workload of schoolwork, domestic activities and paid employment and spend more time on personal care while boys have more free time, especially during early adolescence. Feelings of time pressure for teens increase with age and are significantly higher for girls in both age categories. Gender differences are less pronounced on school days when time is fairly structured, but become more consistent with traditional gender schema on the weekend when time use is more discretionary.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson, R. E. (2002). Youth and information technology. In J. Mortimer & R. W. Larson, (Eds.) The changing adolescent experience: Societal trends and the transition to adulthood (pp. 175–207). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88, 354–364.

Bem, S. L. (1983). Gender schema theory and its implications for child development: Raising gender-aschematic children in a gender-schematic society. Signs, 8, 598–616.

Bianchi, S. M., Robinson, J. P., & Milkie, M. A. (2006). The changing rhythms of American family life. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation Publications.

Biernat, M., & Vescio, T. K. (2002). She swings, she hits, she’s great, she’s benched: Implications of gender-based shifting standards for judgment and behavior. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 66–77.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc.

Eriksson, L., Rice, J. M., & Goodin, R. E. (2007). Temporal aspects of life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 80, 511–533.

Erin Research Inc. (2003). Kids’ take on media: What 5,700 Canadian kids say about TV, movies, video and computer games and more. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Teachers’ Federation.

Fast, J., & Frederick, J. (2004). The time of our lives: juggling work and leisure over the life cycle 1998, no. 4. (Catalogue No. 89-584-MIE). Ottawa, ON: Minister of Industry.

Gager, C. T., Cooney, T. M., & Call, K. T. (1999). The effects of family characteristics and time use on teenagers’ household labor. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 982–994.

Galambos, N. (2004). Gedner and gender role development in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology ((pp. 233–262)2nd.nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Gershuny, J. (2004). Time, through the life course, in the family. In J. Scott, J. Treas, & M. Richards (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to the sociology of families (pp. 158–173). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Hill, J. P., & Lynch, M. E. (1983). The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In J. Brooks-Gunn & A. C. Petersen (Eds.), Girls at puberty: Biological and psychosocial perspectives (pp. 201–228). New York, NY: Plenum.

Hochschild, A. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York, N.Y.: Viking.

Hofferth, S. L., & Sandberg, J. F. (2001). How American children spend their time. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 295–308.

Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1999). Motivational foundations of leisure. In E. L. Jackson & T. L. Burton (Eds.), Leisure studies: Prospects for the twenty-first century (pp. 35–51). State College, PA: Venture Publishing, Inc.

Jacobs, J. A., & Gerson, K. (2004). The time divide: work, family, and gender inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kay, T. (1998). Having it all or doing it al? The construction of women’s lifestyles in time-crunched households. Loisir Et Société/Society and Leisure, 21, 435–454.

Larson, R., & Kleiber, D. (1991). Daily experiences of adolescence. In P. Tolan & B. Cohler (Eds.), Handbook of clinical research and practice with adolescents (pp. 125–145). New York, NY: Wiley.

Larson, R., & Verma, S. (1999). How children and adolescents spend time across the world: Work, play and developmental opportunities. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 701–736.

Marshall, K. (2007). The busy lives of teens. Perspectives on Labour and Income, 8(5), 5–15.

Mattingly, M. J., & Sayer, L. C. (2006). Under pressure: Gender differences in the relationship between free time and feeling rushed. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 205–221.

Messner, M. A. (1990). Boyhood, organized sports, and the construction of masculinities. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 18, 416–444.

Mortimer, J. T. (2003). Working and growing up in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nelson, A. (2006). Gender in Canada (3rd ed.). Toronto, ON: Pearson Education Canada Inc.

Ontario Ministry of Labour (2006). Employment standards at work: minimum age. Retrieved July 18, 2006 from http://www.worksmartontario.gov.on.ca/scripts/default.asp?contentID=1-1-4.

Porterfield, S. L., & Winkler, A. E. (2007). Teen time use and parental education: Evidence from the CPS, MTF, and ATUS. Monthly Labor Review, 130(5), 37–56.

Provenzo, E. F. (1991). Video kids. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ravanera, Z. R., Rajulton, F., & Turcotte, P. (2003). Youth integration and social capital: An analysis of the Canadian General Social Surveys on time use. Youth & Society, 35, 158–182.

Roberts, D. F., & Foehr, U. G. (2004). Kids and media in America. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, C., Tynjala, J., & Komkov, A. (2004). Young people’s health and health-related behaviour: physical activity. In C. Currie, C. Roberts, A. Morgan, R. Smith, W. Settertobulte, & O. Samdal, et al. (Eds.), Young people’s health in context: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2001/02 survey (pp. 90–97). Denmark: World Health Organization.

Robinson, J. P. (1999). The time-diary method: Structure and uses. In W. E. Pentland, A. S. Harvey, M. P. Lawton, & M. A. McColl (Eds.), Time use research in the social sciences (pp. 47–89). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Sayer, L. C. (2005). Gender, time, and inequality: Trends in women’s and men’s paid work, unpaid work, and free time. Social Forces, 84, 285–303.

Shanahan, M. J., & Flaherty, B. P. (2001). Dynamic patterns of time use in adolescence. Child Development, 72, 385–401.

Shaw, S. M. (2001). Conceptualizing resistance: Women’s leisure as political practice. Journal of Leisure Research, 33, 186–201.

Shaw, S. M., Andrey, J., & Johnson, L. C. (2003). The struggle for life balance: Work, family, and leisure in the lives of women teleworkers. World Leisure, 4, 15–29.

Shaw, S. M., Kleiber, D. A., & Caldwell, L. L. (1995). Leisure and identity formation in male and female adolescents: A preliminary examination. Journal of Leisure Research, 27, 245–263.

Silverman, S. S. (1945). Clothing and appearance: Their psychological implications for teen-age girls. New York, NY: Bureau of Publications, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Statistics Canada (2002). Youth in Canada (Catalogue no. 89-511-XPE) (3rd ed.). Ottawa, ON: Minister of Industry.

Statistics Canada (2005). Overview of the time use of Canadians — 2005. (Catalogue no. 12F0080XIE2006001). Ottawa, ON: Minister of Industry.

Statistics Canada. (2006). Education matters: Students in the labour market. The Daily, April 27, 2006. Retrieved March 4, 2007 from http://www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/060427/d060427b.htm.

Todd, J., & Currie, D. (2004). Young people’s health and health-related behaviour: Sedentary behaviour. In C. Currie, C. Roberts, A. Morgan, R. Smith, W. Settertobulte, & O. Samdal, et al. (Eds.), Young people’s health in context: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2001/02 survey (pp. 98–109). Denmark: World Health Organization.

Vernon, M. (2005). Time use as a way of examining contexts of adolescent development. Loisir & Societe/Society and Leisure, 28, 549–570.

Voydanoff, P. (2004). Work, community, and parenting resources and demands as predictors of adolescent problems and grades. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 155–173.

Weinshenker, M. N. (2005). Imagining family roles: Parental influences on the expectations of adolescents in dual-earner families. In B. Schneider & L. J. Waite (Eds.), Being together working apart: Dual-career families and the work-life balance (pp. 365–388). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1, 125–151.

Zeijl, E., Bois-Reymand, M., & te Poel, Y. (2001). Young adolescents’ leisure patterns. Society and Leisure/Loisir Et Societe, 24, 379–402.

Zuzanek, J. (2000). The effects of time use and time pressure on child–parent relationships: Research report submitted to Health Canada. Waterloo, ON: Otium Publications.

Zuzanek, J. (2004). Work, leisure, time pressure and stress. In J. T. Haworth & A. J. Veal (Eds.), Work and leisure (pp. 123–144). London, UK: Routledge.

Zuzanek, J., & Mannell, R. C. (1993). Leisure behaviour and experiences as part of everyday life: The weekly rhythm. Society and Leisure, 16, 31–57.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Institute for Health Information for financial support that enabled the collection and analyses of data reported in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hilbrecht, M., Zuzanek, J. & Mannell, R.C. Time Use, Time Pressure and Gendered Behavior in Early and Late Adolescence. Sex Roles 58, 342–357 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9347-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9347-5