Delphic Oracle's Lips May Have Been Loosened by Gas Vapors

In ancient times, people from all over Europe traveled to Greece to have their questions about the future answered by the oracle of Delphi. Legend has it that she got her powers from vapors. Now, a four-year scientific study supports that notion.

The oracle of Delphi in Greece was the telephone psychic of ancient times: People came from all over Europe to call on the Pythia at Mount Parnassus to have their questions about the future answered. Her answers could determine when farmers planted their fields or when an empire declared war.

The Pythia, a role filled by different women from about 1400 B.C. to A.D. 381, was the medium through which the god Apollo spoke.

According to legend, Plutarch, a priest at the Temple of Apollo, attributed Pythia's prophetic powers to vapors. Other accounts suggested the vapors may have come from a chasm in the ground.

This traditional explanation, however, has failed to satisfy scientists. In 1927, French geologists surveyed the oracle's shrine and found no evidence of a chasm or rising gases. They dismissed the traditional explanation as a myth.

Their conclusion was aggregated by a modern misconception that vapors and gases could only be produced by volcanic activity.

Now, a four-year study of the area in the vicinity of the shrine is causing archaeologists and other authorities to revisit the notion that intoxicating fumes loosened the lips of the Pythia.

The study, reported in the August issue of Geology, reveals that two faults intersect directly below the Delphic temple. The study also found evidence of hallucinogenic gases rising from a nearby spring and preserved within the temple rock.

"Plutarch made the right observation," said Jelle De Boer, a geologist at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, and co-author of the study. "Indeed, there were gases that came through the fractures."

Fractured Landscape

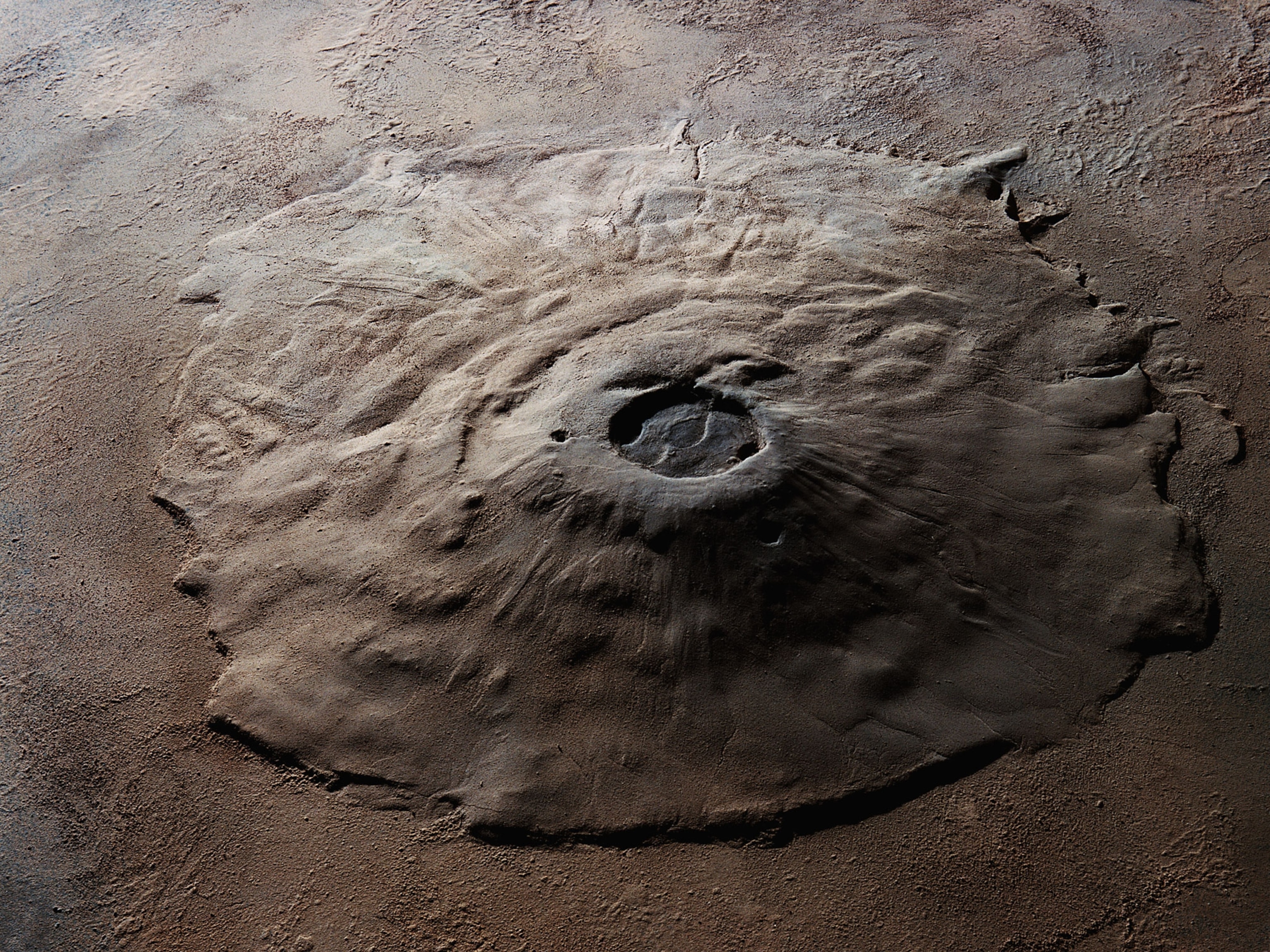

Greece sits at the confluence of three tectonic plates. The shifting of these plates continually stretches and uplifts the area, which is riddled with faults.

Several years ago, Greek researchers found a fault running east to west beneath the oracle's temple. De Boer and his colleagues discovered a second fault, which runs north to south. "Those two faults do cross each other, and therefore interact with each other, below the site," said De Boer.

Interactions of major faults make rock more permeable and create passages through which ground water and gases can travel and rise. From 70 to 100 million years ago, the limestone bedrock underlying the oracle's site lay below sea level, enriched with hydrocarbon deposits.

About every 100 years a major earthquake rattles the faults. The faults are heated by adjacent rocks and the hydrocarbon deposits stored in them are vaporized. These gases mix with ground water and emerge around springs.

De Boer conducted an analysis of these hydrocarbon gases in spring water near the site of the Delphi temple. He found that one is ethylene, which has a sweet smell and produces a narcotic effect described as a floating or disembodied euphoria.

"Ethylene inhalation is a serious contender for explaining the trance and behavior of the Pythia," said Diane Harris-Cline, a classics professor at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

"Combined with social expectations, a woman in a confined space could be induced to spout off oracles," she said.

According to traditional explanations, the Pythia derived her prophecies in a small, enclosed chamber in the basement of the temple. De Boer said that if the Pythia went to the chamber once a month, as tradition says, she could have been exposed to concentrations of the narcotic gas that were strong enough to induce a trance-like state.

Waning Power

The power of the Delphic oracle fluctuated and eventually lost favor as Christianity became the dominant religion of the land, said De Boer. Moreover, ancient legend suggests that the concentration of the vapors became weaker—possibly because the absence of a major earthquake failed to keep Earth's narcotic juices flowing.

Today, the water that helped transport the gases to the Delphic temple is tapped and siphoned above the temple to supply the modern town of Delphi.

The work by De Boer and his colleagues is an example of modern science helping archaeologists understand how ancient peoples lived. Another example among the ancient Greeks is the belief in Poseidon as the god of the sea and earthquakes. According to Harris-Cline, modern science associates the two with tectonic movement deep under the sea.

"Our scientific techniques are just beginning to detect the natural phenomena which the Greeks celebrated and appreciated 2,500 years ago with ritual activities at these special places," she said.