Bring visual accessibility into focus with tools, workplace culture

Financial advisory firms need to be sure that clients are able to read documents, and providing that access is an ongoing process.

“I lost money because I wasn’t able to independently manage what I needed to manage,” said Albert J. Rizzi.

That was years ago, when Rizzi was still adjusting to losing his sight in 2006 as the result of a bout of fungal meningitis.

He’d requested key documents from his Morgan Stanley financial adviser in an electronic format so that his computer’s screen reader could translate it to audio. But the firm sent an unreadable PDF.

Rizzi sued and eventually settled.

Now, through My Blind Spot Inc., the advocacy and consulting nonprofit he founded and runs, Rizzi works with financial services companies to help ensure that they equalize access to materials for people with compromised vision.

“Everyone will join this club, whether by accident, illness or aging,” said Rizzi of the estimated 32.2 million adult Americans (about 13% of the population) who must rely on adaptations to see and understand printed material.

As a matter of law, not to mention operational risk, financial advisory firms must ensure that clients can read documents, said Jessica B. Weber, a partner with law firm Brown Goldstein & Levy. Complying with basic standards of visual accessibility is a start, but firms also elevate client service and minimize risk when they proactively design print and digital materials for varying levels of visual ability.

That’s especially important because visual acuity changes as people age. Eyesight often deteriorates but then is restored: Cataract surgery is one of the most common procedures in America. “As the population ages, they might not identify as people with disabilities, even though they have trouble seeing or walking,” Weber said. “It’s important to proactively plan and include tools.”

A common misconception is that simply offering digital versions of documents absolves a business of any further accommodation, said Timothy Springer, CEO of accessibility compliance consulting firm Level Access.

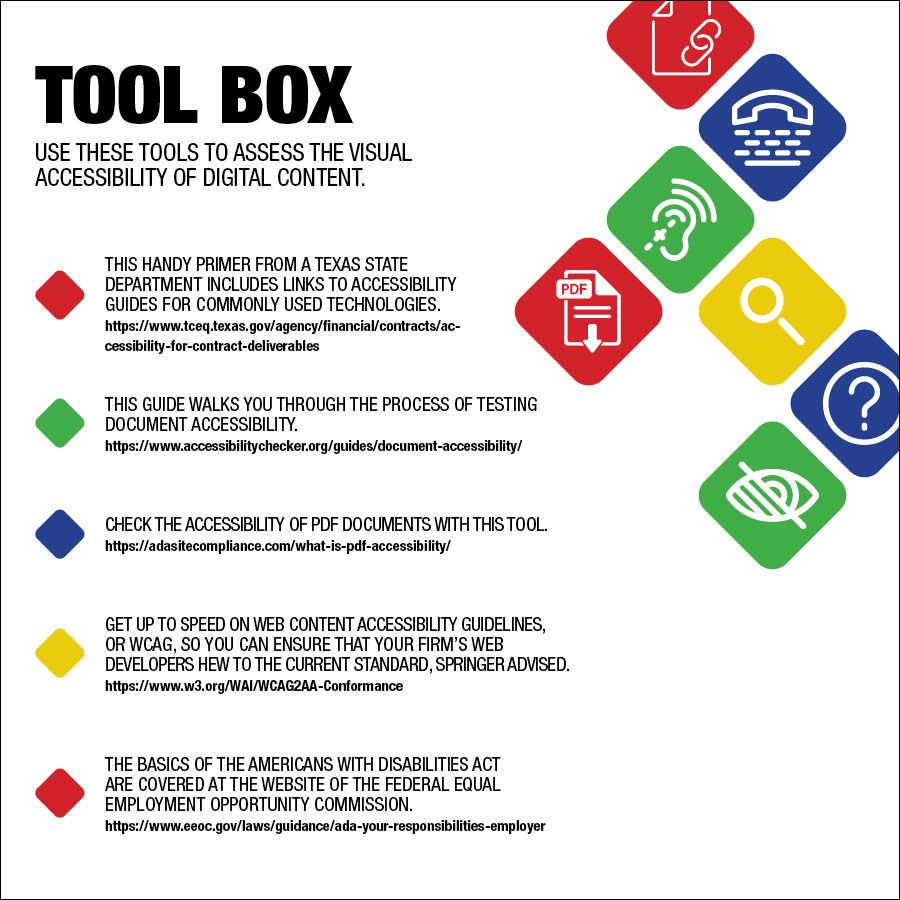

The truth is more complicated. Visual accessibility is an ongoing process. Digital design needs to be tested for all commonly used formats, including mobile screens, so that material organically “reflows” into a coherent format that allows clients to easily find, say, key links no matter how large the print is on their screen, Springer said. In addition, each legal and financial document, including client reports and spreadsheets, needs to be equitably available in several formats, from large print on paper to digital formats that interface smoothly with accessibility tools like screen readers. Footnotes and other supporting material must be equally readable.

“You can’t ask someone to sign a document they can’t read,” Springer said.

Risk is further complicated by privacy requirements, said Jason C. Taylor, chief innovation strategist and with accessibility consulting firm UsableNet. “If you create an environment that makes one of your clients say, ‘Can you read this for me?’ privacy and security is gone,” he said. “The risk is that either people if they can’t read a document but sign it anyway, or they get someone else to read it to them and there goes their privacy and security.”

Visual accessibility isn’t a “set it and forget it” process, either, said Springer, Rizzi and other consultants. Digital layouts and the technical underpinnings degrade as new functions and elements are added, potentially canceling out once-helpful designs and links. Testing for the experience of a visually compromised client (by a visually compromised or professional tester, not by a person with normal sight) should be integral for confirming good user experience ongoing, consultants said.

MULTIGENERATIONAL RELEVANCE

Vision ability intersects with personal preference, too, pointed out Parinay Malik, director of customer inclusion at Fidelity Investments, which outlines its visual accessibility tools for clients. Some people, accustomed to controlling font size through e-books, have come to prefer larger fonts, he said.

“Captions work for almost everybody,” Malik said, especially as consumers become familiar with toggling through preferences offered by digital entertainment platforms. And older clients often rely on younger family members for visual work-arounds, which means that firm staff must customize visual access for two generations.

All of this means that ongoing visual accessibility compliance is achieved through workplace culture. Malik and others agree that staff need to be ever-aware that clients, especially long-time clients whose visual ability might have changed, are always offered visual options.

Taylor said that a good way to approach clients is with an open-ended question: How do they prefer to take in the information?

And it’s paramount, Weber said, to make sure that tools and options are always ready to be used, whether that’s in-office signage or digital documents that are confirmed to be compatible with screen readers.

“When you’re scheduling appointments, have a notation that asks clients if they need an accommodation, so you have advance notice,” she said. “Then have these arrangements set up so you are ready to go.”

[More: Visual accessibility serves clients more effectively, heads off potential risk]

Learn more about reprints and licensing for this article.