How Redistricting Became a Technological Arms Race

Advances in data, computing, and fundraising have given politicians new power to gerrymander democracy away.

These ain’t your grandfather’s gerrymanders.

Gone is the era of elaborate cartographical sketches and oil paintings of salamanders, and of salted old-timer politicians drawing up their “contributions to modern art” armed with markers and heads full of electoral smarts. Today, political mapmaking is a multimillion-dollar enterprise, with dozens of high-profile paid consultants, armies of lawyers, terabytes worth of voting data, advanced software, and even a supercomputer or two. Redistricting is the great game of modern politics, and the arms race for the next decade’s maps promises to be the most extensive—and most expensive—of all time.

Republicans certainly maintain the advantage in that game right now. They began the escalation over seven years ago, with the creation of the groundbreaking REDMAP initiative. As David Daley’s Ratf**ked illustrates, the first goal of the Republican State Leadership Committee’s REDMAP project was to seize control of vulnerable statehouses in purple states in the 2010 elections and grab ahold of the redistricting process, which by the Constitution occurs alongside the reapportionment of Congressional seats every 10 years with the results of the Census. With those seats in hand, the resulting end goal was not some shady conspiracy, and REDMAP’s own website proudly sums it best: “The party controlling that effort controls the drawing of the maps—shaping the political landscape for the next 10 years.”

REDMAP was a spectacular success. First, on the strength of fundraising efforts in pivotal states with changing demographics—places like Wisconsin and North Carolina that have become new swing states—Republicans overran 2010 state legislative races in backwoods districts, to the tune of nearly 700 state legislative seats, the largest increase in modern electoral history. Additionally, Republicans outspent Democrats by over $300 million in that year’s gubernatorial races, which netted them six additional gubernatorial positions, including the coveted governor’s mansions in Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, which were all flipped from Democratic incumbents.

The Republicans’ two-pronged legislature and governor’s mansion strategy was vital, since political maps often require two levels of political approval in many states. “State legislatures will draw the maps and governors will sign the maps,” says Kelly Ward, the former executive director of the DCCC and now the executive director of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee. Although the Democratic strongholds of Maryland and Illinois are also known to be heavily gerrymandered, by beating Democrats at multiple levels everywhere else in the creation and oversight of elections law, Republicans could ensure unfettered power over creating maps, which with their technological and expertise advantages could then be used to redouble the advantages they’d just gained, in perpetuity. And in a case currently before the Supreme Court, the power to engineer gerrymanders that entrench political power for one party could soon be limited—or forever given the imprimatur of legitimacy.

To be sure, the extent of those advantages is still a matter of debate. The party line among Republicans is that Democrats have used the specter of gerrymander as a way to excuse lackluster politics. Matt Walter, the president of the Republican State Leadership Committee—the parent organization of REDMAP—agrees. “I think the reason that [redistricting] is attracting so much attention now,” Walter says, “is that having abysmally failed at virtually every level of government from presidential down to the state levels to run good candidates and to be successful in campaigns over the past several elections, the Democrats have been figuring out some way to rationalize that and figure out a way back.”

But let’s back up a bit. How exactly does redistricting work, and how did a project like REDMAP play out in practice? The Constitution doesn’t specifically outline a redistricting process, merely requiring proper apportionment of representatives to constituents. But in the redistricting processes that have developed since, politicians and parties with the most to gain from redistricting have generally owned them, which means they’ll usually do what they can to maximize party advantage.

Over time, more protections against rampant party manipulation have been built. The first layer of defense against politicians creating totally incoherent maps and gaming the republican system is found in the Equal Protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. As outlined in the Supreme Court ruling in the 1962 Baker v. Carr case, states have to redistrict every ten years in a way that keeps up with population shifts and keeps every district roughly equal in population. That’s called the “one person, one vote” rule.

Layered over that basic foundation are the laws that have dictated just how to truly guarantee equal protection under the law. Chief among those is the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which both prohibits the use of maps to dilute minority voting power and also dictates certain conditions under which creating special districts to protect them is required. On top of the VRA are further layers of court interpretations, tests, and principles—including the compactness and contiguity of districts and how well they preserve special communities of interest—that guide court decisions.

Under those rules, politicians are free to some extent to use redistricting for partisan advantage, sometimes bending or breaking the rules in the process. In practice, that means that national party infrastructures build coordinated redistricting efforts across states, during which they pour money into winning states each decade and then bring small armies of lawyers, consultants, and cartographers to create the new maps, which they then shepherd through rounds of public scrutiny, legislative battles, and then the inevitable court challenges and legal reviews that come up for any remotely controversial maps.

The incentive to gerrymander—or create irregular and incoherent districts that may or may not be legal—is strong. Although the Supreme Court has held that using redistricting to create partisan advantage can be unconstitutional, it also holds that some level of partisan gerrymandering is acceptable, and has so far declined to rule on where the line is, or if it can even determine a line at all. That means that as long as they can avoid the ire of the courts, politicians can use maps to corral opposing party’s voters in a few districts and create unbreakable party fiefdoms out of the other districts. The main limitations to gerrymandering outside of the courts have historically been the other party’s ability to fight gerrymanders (or create their own when in power) and the lack of precision in map-making capabilities.

According to John Ryder, the former general counsel of the Republican National Committee and the RNC Redistricting Committee chair during the 2010 redistricting cycle, “for the two parties, it’s both offense and defense. Parties try to try to maximize their opportunities and minimize their losses.” Ryder is a titan within the Republican redistricting brain trust, and has helped guide the party’s efforts for decades now. He cut his teeth challenging Democratic state maps in his native Tennessee, long a hotbed of gerrymandering challenges and the place where the foundational Baker v. Carr case created the modern gerrymandering game.

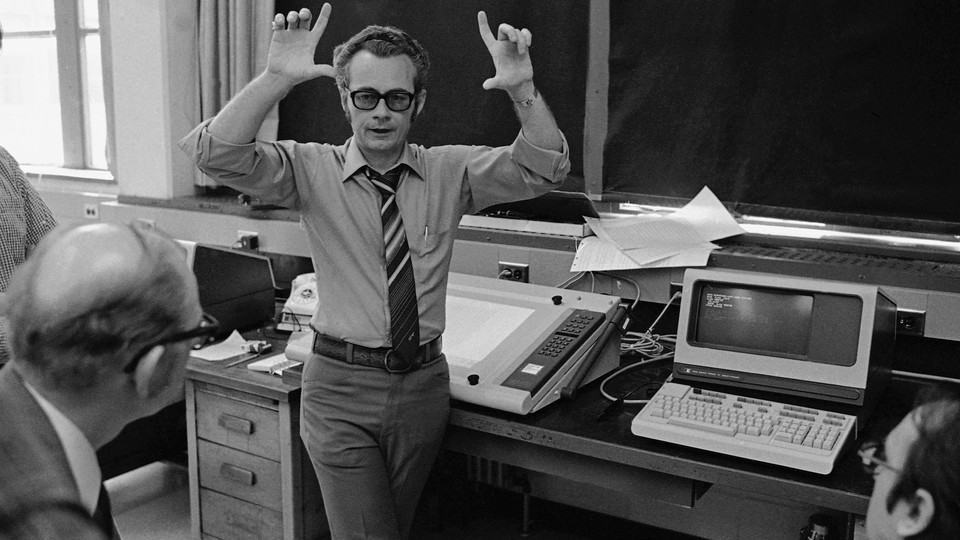

“When I started doing this in the mid-70s,” Ryder told me, “we were using handheld calculators, paper maps, pencils, and really big erasers. It was pretty primitive.” Even into the beginnings of the digital era, mapmaking was limited by computing power, the incredible burden of data management, the cost of hardware, the unwieldiness of computers, and the use of giant, slow map printers that literally drew maps with big markers. Through most of Ryder’s career, neither party really had the technology, expertise, or investment in redistricting to break open a national advantage.

That began to change in the ‘90s. By the 1990 redistricting cycle, much of the process had gone digital, but it wasn’t very precise. Although expensive minicomputers had already been supplanted by smaller and more powerful machines, they were still the primary platforms for redistricting software, which itself often could cost thousands of dollars. The process relied on massive amounts of Census data—including what are known as TIGER shapefiles that contain the geographic information in play—that were free, but often required expensive manipulation by outside corporations in order to be accessible. On top of the direct costs, the software was cumbersome and prone to error, came with massive manuals, and often required users to directly input long strings of code and commands to even get started.

The Caliper Corporation was a bit player in the mapping software markets then. The startup had almost accidentally come up with a desktop Geographic Information System—or GIS, the kind of software under which most modern mapping programs fall—around 1990, originally intended for use by transportation officials. But it was one of the first mass-market programs that could handle raw TIGER files, which attracted attention among the broader cartographical community. Caliper moved to create a more generalized application from the specialized transportation program and called the resulting desktop GIS software GIS Plus.

It wasn’t long before state officials got wind of the new program, and turned to Caliper and its president Howard Slavin for advice. “We came out with this product kind of in the middle of the 1990 redistricting cycle,” Slavin told me. “And we realized that this GIS Plus product was pretty good for redistricting.”

GIS Plus hit all the marks for savvy officials who wanted an edge in redistricting: It was cheaper than existing programs, ran on desktop computers, could digest Census data products, and required a much less monumental learning curve. It was also critical for outside entities who had no access to the backroom mapmaking processes and giant computers that state officials shelled out thousands of dollars for for a process that only happened once a decade. “It turned out that a whole bunch of people who wanted to become involved in redistricting, but didn’t have the big bucks came to us,” Slavin said. “The NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and lots of other minority groups used our product because it worked and it cost about $3,000 instead of hundreds of thousands of dollars. And it was also easier.”

1990 was a proof-of-concept, both for the burgeoning redistricting-industrial complex and for Caliper. The developer went from dipping its toes in the redistricting market to a full-scale commitment for the 2000 cycle, when it scrapped plans to make cheap redistricting extensions for existing software and created a brand new series of software called Maptitude, which features a special redistricting version. That version was more expensive than the jury-rigged GIS Plus copies that led the way in 1990, and also allowed even people who had very little training in mapping or programming to get their hands dirty and import voting data with ease.

Republican operatives saw an opportunity during the 2000 cycle, and adopted Maptitude at every level, adding a technological edge to a considerable organizing and funding lead and a surge in control of statehouses. Democrats were left scrambling, and largely lagged behind an increasingly sophisticated redistricting effort on the other side.

By 2010, Republicans were ready to turn the gap between the parties on all things redistricting into a chasm. Their aggressive campaign of sophisticated redistricting—often resulting in hyper-gerrymandered districts that had never been seen before—took not only Democrats off guard, but also members of the larger community of parties interested in redistricting. “We did not expect that Republicans would end up using this in the way they wound up using it, but that happened,” Slavin told me.

But use it that way Republicans did, and the REDMAP project, masterminded by former RNC chairman and current Virginia gubernatorial candidate Ed Gillespie, was a perfection of the strategies pioneered over the preceding decades.

With the levers of redistricting in vital areas firmly in party control, then it was time for the GOP consultants to pour into statehouses in 2011. A 2012 article in the pages of this magazine illustrates how that process worked via the example of Tom Hofeller, perhaps the most well-known—and notorious—of the Republican redistricting consultancy:

And so his cyclical travels take him mainly to states where the Republicans are likely to be drawing the new maps. (In most states, an appointed committee consisting of legislators from the majority party produces the map, which is then brought to the legislative body for a vote. Other states relegate the duties to an appointed commission.) At meetings, Hofeller gives a PowerPoint presentation titled “What I’ve Learned About Redistricting—The Hard Way!” Like its author, the presentation is both learned and a bit hokey, with admonitions like “Expect the unexpected” and “Don’t get ‘cute.’ Remember, this IS legislation!” He warns legislators to resist the urge to overindulge, to snatch up every desirable precinct within reach, when drawing their own districts.

State parties themselves have little control of the process; rather, analytic consultants in the mold of Billy Beane came down and played “Moneyball” with the districts on the national party’s dime. Most of them used Caliper’s Maptitude program, and by 2010 both the software and the available data had become sophisticated and deeply specialized. According to Michael Li, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice, “certainly, technology has gotten a lot more sophisticated, and it’s enabled map drawers to draw much more durable gerrymanders than they have in the past. That’s because state mapmakers now know a lot more about voters. That’s just an extension of the big data revolution that you also see in marketing and other politics.”

GOP consultants and some redistricting experts challenge the idea that increasing sophistication of redistricting has led to polarization, and often argue that redistricting merely reinforces a tendency for Democrats to cluster in cities, and solidifies a natural Republican geographic advantage—an argument about “spatial polarization.” Ryder told me that “I do not believe that redistricting is as powerful a weapon as perhaps some others do, in part because of this factor of spatial polarization.” Even researcher Jowei Chen at the University of Michigan, whose pioneering work has been instrumental to opponents of gerrymandering, said in a 2014 New York Times op-ed that “the Democrats’ geography problem is bigger than their gerrymandering problem.”

But those explanations fall short of explaining just why parties have ramped up redistricting efforts so heavily in the past three decades, and why Republicans especially have dug deep into the field of big data in order to gain advantages, including the use of consumer data and other huge political datasets in order to achieve one of the holy grails of redistricting: microtargeting below precinct lines.

Normally, precincts are the lowest level at which aggregated official political data is available. That makes sense, since precincts as designated and created by towns and counties are the primary unit of elections administration. But, with the rise of big data and big datasets, mapmakers have been able to scry—with remarkable accuracy—both the political leanings and voting likelihood of blocks and households, which then allow them much more fine-tuning of district lines. Whereas the previous generation of mapmakers may have been able to split some precincts based on some well-known neighborhood characteristics (say a neighborhood that was known to be integrated in an otherwise all-white community), in 2010, they gained a remarkable amount of precision and could place individual voters in buckets and then districts.

Some states restrict the available redistricting datasets in order to reduce this kind of microtargeting, but Republicans found a way around those restrictions as well. “A lot of the redistricting plans we’ve seen have split precincts in drawing lines,” says Allison Riggs, a senior attorney at the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, an organization that has challenged several redistricting plans. “When you split a precinct, all of the voter data—voter registrations and returns—kept at a precinct level, is lost. If you split a precinct, some of the only information available at a sub-precinct level is race data. It’s the Census data, which is available at a block level.”

In North Carolina, which has been at the center of seemingly every elections-law controversy in the past decade, the number of precincts split by 2011 House and state General Assembly maps reached almost comical levels. In the Dickson v. Rucho case, one of the slate of lawsuits over North Carolina maps that reached the Supreme Court, plaintiffs alleged that the three plans “divide 563 of the state’s 2,692 precincts into more than 1,400 sections.”

In those 563 problem precincts, the plaintiffs found a number of absurd scenarios. In one, “residents of one-and-a-half blocks of a small neighborhood street will receive three different ballot styles for the [2012] general election.” In another precinct, over the course of an election cycle, 18 different sets of ballots would have to be printed. And those problems weren’t unique to North Carolina’s electoral snafus: the 2011 maps in Virginia tripled the previous number of split precincts, and a coalition of voters of color in Texas alleged in 2011 that state lawmakers surgically split precincts in order to dilute Latino voting strength.

While that kind of tinkering didn’t dramatically reshape a whole lot of districts that had already been deeply gerrymandered by years of partisan mapmaking, the results of such micromanaging in the aggregate seem undeniable. Over the course of three elections since redistricting, North Carolina’s seats in Congress shifted from a 7-6 Democratic advantage to a 10-3 Republican advantage, an advantage ever more at odds with simulated delegations that predict a 7-6 or 6-7 split. In the 2012 elections, North Carolina, Virginia, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Florida, and Indiana featured an average margin of victory of seven percent by Republicans in the total vote share, but a 76 percent advantage by Republicans in seats in the House. That same year, in Wisconsin Republicans only captured 48.6 percent of the state Assembly votes, but still garnered over 60 percent of its seats.

The most remarkable thing about those outcomes—which might appear undemocratic just on their face—is just how blatant the Republican strategy was. REDMAP’s goals are still up on its website. In North Carolina at least, constituents reported that mapmakers in the General Assembly shifted around mapmaking feedback sessions or simply ignored comment from outraged citizens. And anyone with access to the same kind of mapmaking arms that GOP consultants had could check their math and see just how distorted the districts were.

Many did, and that’s perhaps where the sudden aggressiveness of Republicans may have worked against them. “What we started seeing post-2010 was some of that software being more accessible to the public,” says Riggs. “There was even one decent online app that would allow citizens to redraw Congressional district lines. I anticipate that trend continuing such that by the time we come to the 2020 Census and the redistricting cycle that starts the following year that there will be even more programs online accessible to folks to draw maps.”

The increasing availability of computing power and of political mapmaking software empowered the groups that would launch a slew of challenges to gerrymanders. Justin Levitt, a law professor at Loyola Law School and an expert on redistricting, has kept track of these cases—and has testified in a few. “Since 2010, I’ve counted about 233 total challenges to the validity of state maps,” Levitt told me. “That’s not super dissimilar from 2000 or 1990; litigation is a sure thing. But you are starting to see the courts take an aggressive role towards policing harmful racial gerrymanders.”

Levitt stresses that technology has aided in successful challenges and has given power to citizen-led groups and partisan actors alike to challenge single-party dominance in mapmaking. “If you go back to Phil Burton, a representative in California drawing the maps in California with not much more than a roadmap and a pen, they were pretty precisely able to target exactly the pockets of voters they wanted to,” Levitt says. “There are more politicians able to do what the Burtons were able to do because of technology, but most importantly there are more of us who aren’t politicians who can do what the Burtons were able to do, and who are able to see the impact of the sorts of things the Burtons were able to do. It’s opened up the process so that many individuals and groups can have a swing at both recognizing what current districts and new proposals do, and also finding their own way into the process.”

The groups that have joined the technological arms race read like a who’s who among Supreme Court plaintiffs over the past few years. There’s the NAACP and its constituent chapters, the independent NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the League of Women Voters and its chapters, the Brennan Center, and a host of other smaller firms that have been empowered by the relative availability of redistricting tools via private and nonprofit sources. And as seen in cases like Cooper v. Harris and Covington v. North Carolina in North Carolina, when it comes to racial gerrymandering as restricted by the Voting Rights Act, plaintiffs have been uncommonly successful in sustaining complaints and using their own analytic tools to turn the scrutiny of courts to ever-more subtle breaches of the law.

Technology has also opened up the front of much more sophisticated means of challenging gerrymanders. Chen’s cutting-edge research has involved supercomputers and the use of simulations of hundreds of different possible maps in order to identify whether politician-drawn maps deviate deeply from expectations. “Something we’ve seen just in the last three or four years alone is a huge advance in some of the expert analysis of redistricting plans,” says Riggs, who has used these new tools in successful court challenges of multiple levels of gerrymanders. “What that allows us to do is to say ‘this plan that state X has enacted falls way outside the range of what you might expect redistricting plans to produce with basic criteria.’”

Those kinds of sophisticated analyses and simulations have also cast definitive doubt on the popular GOP contention that geographic sorting is more related to their ascendancy than gerrymandering. A July 2017 AP analysis of U.S. House and state legislature seats found that Republicans enjoyed consistent electoral advantages at all levels above their vote share. The Princeton Gerrymandering Project’s simulation analysis of 2016 U.S. House maps found that North Carolina, Michigan, and Pennsylvania failed all three of its gerrymandering tests, indicating consistent Republican advantage and a bias that can’t be explained by geography. The same project found that North Carolina, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Mississippi all failed those tests in 2016 state-house races as well.

This increasingly sophisticated battle between the politicians in charge of redistricting and their opponents has perhaps reached its zenith in a case currently being argued before the Supreme Court. The Gill v. Whitford case, which parties argued on October 3, has the potential to redefine their battle, and could offer either new tools for scrutinizing political maps or new cover to potential gerrymanders, depending on what the justices decide.

While the proliferation of new tools has seemingly increased both the rate of gerrymandering and the rate of successful challenges of those gerrymanders, so far all of that work has been done on the racial gerrymandering front. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 and subsequent court interpretations of that act and its revisions lay out some specific guidelines on when to look for racial gerrymanders—and when they are considered constitutional or not. The VRA actually compels mapmakers to consider race and bend maps to create majority-minority districts when a specific set of guidelines are met. Those preconditions are based in the political and geographic cohesion of the minority group in question, and on the likelihood of that group ever electing the candidate of its choice if not allowed a special district.

As illustrated in North Carolina’s first round of gerrymandering cases, racial gerrymanders are relatively easy to spot and challenge in court. In the Cooper v. Harris decisions, plaintiffs successfully argued that state GOP’s 2011 congressional map that increased the black voting-age population (BVAP) by four percentage points in District 1 and seven percentage points in District 12 was unconstitutional, since white voters didn’t tend to vote against black-favored candidates in District 1, and since the Court found that mapmakers violated previous specific court orders to avoid using race in the creation of District 12.

But in the next round of gerrymandering cases, the same GOP lawmakers after their Court rebuke in 2016 decided to draw new districts based purely on party identifiers that preserved Republican advantage. Several groups of plaintiffs sued, claiming that these new maps constituted partisan gerrymanders. But there is remarkably little legal guidance on just what constitutes a partisan gerrymander.

That issue is also at the heart of Gill v. Whitford, a case that percolated through federal courts to the Supreme Court after six years of legal drama. In 2011, Wisconsin GOP lawmakers used the opportunity of redistricting to create perhaps the most durable advantages of any single party in an American state—again, creating an electoral map that gave such a boost to Republicans that they could lose the overall vote totals and still pull in well over half of the seats in the state assembly. While the party eschewed the use of race factors that had so troubled their colleagues in other states, numerous qualitative and quantitative analyses found that their partisan factors—which themselves stand as reasonable proxies for race in many places—had created a major advantage.

Those analyses are the key question in Whitford. According to Jessica R. Amunson, an attorney who’s worked on multiple partisan gerrymandering cases as they’ve evolved in the courts and a lawyer for the plaintiffs in this case, this case is the culmination of an long analytical arms race. “Many partisan symmetry metrics have been developed and honed since the Court’s decision in Vieth and since Justice Kennedy’s opinion in the Vieth case,” Amunson says.

In that case, 2004’s Vieth v. Jubelirer, Justice Antonin Scalia’s decision on Pennsylvania congressional districts “concluded that political gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable because no judicially discernible and manageable standards for adjudicating such claims exist.” But Kennedy wrote in response that “if workable standards do emerge to measure these burdens … courts should be prepared to order relief.”

"There’s been a lot of academics working on various measures since then," says Amunson. The newest metric to reach the Court in Whitford is the “efficiency gap,” a tally of the “wasted” votes that happen either when a voter votes for a losing candidate or when a voter votes for a candidate who would have won anyways. That metric was created by Nicholas Stephanopoulos, a professor at the University of Chicago School of Law, and Eric McGhee, a research fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California.

“In 2006, when Justice Kennedy criticized the partisan bias measure, five members of the Court seemed to be interested in some kind of better measure of partisan gerrymandering,” Stephanopoulos told me. “Partisan bias asks: ‘If we had a hypothetical tied election, how different would the shares of seats be in that election?’ Justice Kennedy actually criticized that metric in the 2006 [League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry] case.”

“Eric and I agreed with Justice Kennedy that we shouldn’t be conceptualizing partisan gerrymandering as what would happen in a hypothetical election,” Stephanopoulos continued. “We should be looking at what happened in actual elections, instead of trying to simulate—with fairly speculative techniques—outcomes in counterfactual situations. Eric had that insight and came up with his efficiency gap measure, which doesn’t rely on any hypotheticals or counterfactuals. It’s a metric that’s purely based on the actual election results.”

In the case of Wisconsin, that metric found an incredible asymmetry in the Wisconsin assembly maps, where Democrats are often in ultra-safe districts that in turn draw away Democratic voters from races where Republicans win more narrowly. Stephanopoulos’s and McGhee’s work shows double-digit statewide efficiency gaps in favor of Republicans in each election cycle since the 2010 redistricting.

As Stephanopoulos himself notes in an essay outlining his formula for Vox, the efficiency gap alone doesn’t do the job of marking a partisan gerrymander by itself. Old measures of partisan bias, lopsided wins, and mean-median difference still showed up in presentations to courts. And more sophisticated analyses also took stage. The whole supercomputer simulation thing—run by Jowei Chen—was used to generate theoretical Wisconsin assembly maps and then compare their efficiency gaps to Wisconsin’s actual situation. Chen’s simulation found that “144 of the 200 random districting plans produced by the non-gerrymandered computer simulation process exhibit an efficiency gap of within 3 percent of zero, indicating no substantial favoring of either Democrats or Republicans.” The remaining 56 simulations actually showed a slight natural favor to Republicans, but nothing approaching the double digits consistently encountered in the state.

These new advanced metrics may or may not sway Justice Kennedy, but more of these kinds of analyses will become the norm as gerrymandering itself becomes more and more complex, and as the ability to construct partisan advantages during redistricting increases. Whitford itself represents a sort of watershed case for gerrymandering: Here is where the end result of the most intricate, expensive, and contentious redistricting process in history meets the maturation of an analytical field created to rein it in, all under the aegis of a Constitution that did not foresee microtargeting and GIS.

As such, the real arms race ahead appears to be between citizens and their elected officials. As redistricting become more opaque, more sophisticated, and increasingly the domain of a multimillion-dollar party apparatus, it will be up to voters and the courts to level the playing field, both through democratizing technology and direct democratic measures. This is a uniquely American adversarial relationship between politician and constituent—most other functional democracies seem to have the good sense to not put politicians in control of who gets to elect them.