Hurricane Otis Was Too Fast for the Forecasters

The storm intensified to Category 5 just before it reached Acapulco.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

In the hours before Hurricane Otis made landfall, everything aligned to birth a beast. The hurricane, which arrived near Acapulco, Mexico, early this morning, had an improbable combination of terrible traits. It was small and nimble, as tropical storms go, which reduced the amount of data points available to forecasters and made it harder to track. It came toward land at night, which is the least ideal time for a chaos-inducing event to hit a population center. Winds in the upper atmosphere were moving in exactly the way that hurricanes like. Its compact size also meant that it didn’t need as much energy to become ferocious as a more sprawling storm would. And energy in its particular patch of superheated ocean was in no short supply.

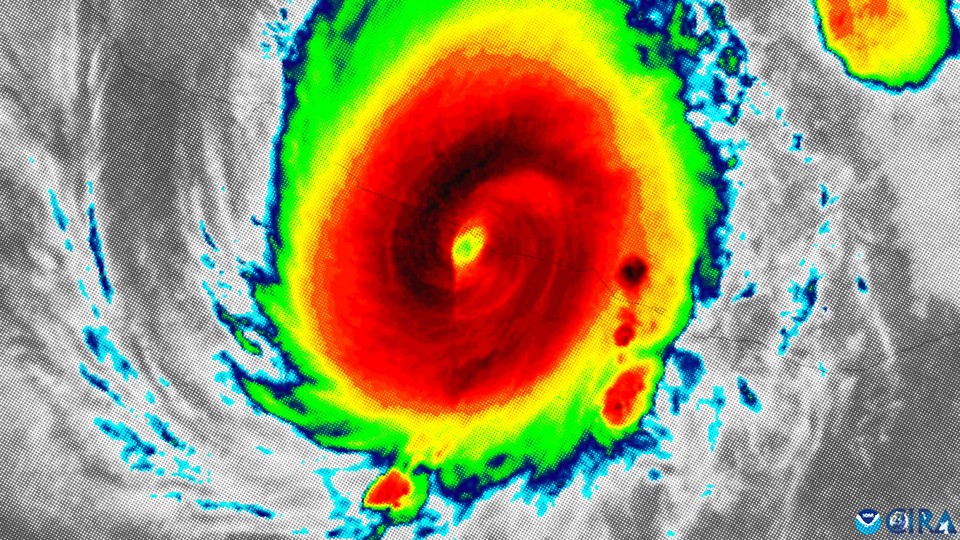

Yesterday morning, Otis was merely a tropical storm. Then the system moved over a near-shore patch of hot water, where the sea-surface temperatures reached 31 degrees Celsius in some places (88 degrees Fahrenheit). It “explosively intensified” in a “nightmare scenario,” according to the National Hurricane Center, gaining more than 100 miles per hour of wind speed in 24 hours. Suddenly, the tropical storm became a Category 5 hurricane just before reaching Acapulco—home to 1 million people—at 12:25 a.m. local time. And no one saw it coming.

A short 16 hours before Otis made landfall, the National Hurricane Center predicted that it would come ashore as a Category 1 storm. Jeff Masters and Bob Henson, both veteran hurricane specialists, called that “one of the biggest and most consequential forecast-model misses of recent years.”

You can watch the line tracking the storm’s speed sprint through the levels of hurricane intensity. “We never truly expect that rate of intensification. It is incredibly rare,” Kim Wood, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Arizona who has studied hurricane behavior in the northeastern Pacific for the past 10 years, told me. With so few similar storms, predictions are harder to make. “I don’t want more points of comparison,” they said. “If the storms could not do this, that would be great.” But, they added, “it does seem to be increasingly possible.”

A hot ocean is hurricane food. “Hurricanes are heat engines,” Masters told me. “They take heat energy from the oceans, in the form of the water vapor that they evaporate from it, and convert it to the kinetic energy of their winds.” And if a particular patch of ocean is hot enough, and a well-organized storm happens to pass over that spot, that conversion can happen in the hurricane equivalent of an instant.

Although climate change won’t necessarily cause more storms to form—certain climate-related wind dynamics may actually discourage storm formation—the ones that do form have a higher chance of becoming extremely strong, mostly thanks to warming oceans, both Wood and Masters said. In 2017, Kerry Emanuel, now a professor emeritus at MIT, whom Masters called “one of the top hurricane scientists out there,” published a paper exploring whether hurricane prediction was about to get a lot harder. The answer it came to was essentially yes: “As the climate continues to warm, hurricanes may intensify more rapidly just before striking land, making hurricane forecasting more difficult,” Emanuel wrote. That’s exactly what happened with Otis.

As rapid intensification becomes more commonplace, Masters said, funding for hurricane prediction is crucial. “We need more observations; that’s the critical thing. And better computers for making models, and just more money to fund more people doing the research to get things right, to take that data and make a better forecast,” he said. “It takes all these things.”

As the storm passed through Acapulco, the power cut out, and communications did too. A landslide made the main highway impassable. So far, the details of the storm’s damage are still unclear—but given the short warning, in a place that has never seen such a strong storm, it likely had devastating consequences. “The damage and the death toll are very likely going to be quite a bit higher than if they had been prepared for it,” Masters said. The benefit of hurricane forecasting is not just knowing what’s coming, but having time to act before it hits. Once a storm has formed, no one can control it; all anyone can control is what we do before the next time.