The app for independent voices

Past societies produced so much beauty because they knew that math and beauty are deeply connected.

It all started when Pythagoras discovered something mind-blowing about reality:

The universe is not made of matter, but music...

When walking past a blacksmith’s forge over 2,500 years ago, Pythagoras noticed a strange harmony in the clanging of hammers. He realized that two hammers make a harmonious sound if one is exactly twice as heavy as the other.

He worked out that this 2:1 weight ratio produces an octave (notes separated by an octave sound alike). Likewise, a 3:2 ratio creates a perfect fifth, and 4:3 a perfect fourth. This evolved into our musical scale of today.

But it wasn't just weight — a note's pitch is also inversely proportional to the length of the string that produces it. Pythagoras had discovered that sounds can be harmonious together because of a mathematical relationship between them.

This got him thinking: if music is essentially math, perhaps the universe itself is also governed by mathematical patterns?

Eventually, Pythagoras came to the idea that the universe and everything in it could be understood in those same terms. As math and music are interconnected, the universe too is musical, and physical matter is merely music solidified.

He developed a theory called the "music of spheres," intuiting that celestial bodies "hum" a kind of music as they move, unheard by human ears:

There is geometry in the humming of the strings, there is music in the spacing of the spheres.

Followers of Pythagoras mapped the sun and planets, assigning each a unique tone based on their orbits and distances from Earth. We cannot hear this music with our ears, but it's heard by the soul.

Pythagorean thinking carried into the Middle Ages, with Boethius explaining the 3 kinds of music:

Musica mundana: unheard music of the cosmos

Musica humana: harmony between body and soul

Musica instrumentalis: audible music of instruments and voices

These weren't just radical, isolated theories. This worldview permeated society for centuries. People believed the universe was bound by a mathematical, musical harmony.

For example, if you went to university in the Middle Ages, you learned music as one of four sciences of the quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

The idea was that music, math, and the cosmos were inextricably linked. The universe was deeply mathematical and God must himself be a divine geometer.

So, if the universe is one great musical composition, how do you live your life to be in tune with it?

Well, by making music that connects you to that divine order for one; but you can do it in visual art, too. Art from antiquity to the Renaissance and beyond tapped into that mathematical order.

The Golden Ratio fascinated artists from Da Vinci to William Blake, who knew mathematical harmony touches us with a sense of otherworldly calm. In architecture, cathedral builders wove Gothic facades with immensely complex geometry.

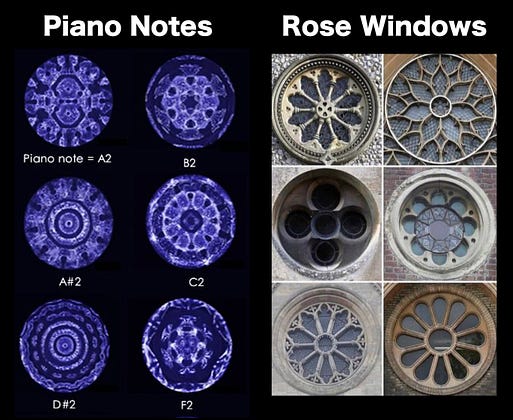

As Pythagoras had found harmony in the mathematical order of music, geometry could produce visual harmony. Music and visual beauty were bound by the same divine forces — notice the similarity of vibrations of musical notes in water and rose windows, for example.

In the words of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe:

Music is liquid architecture; architecture is frozen music.

Medieval people's obsession with math might seem strange or unnecessary to the modern-day architect — but the results speak for themselves…